Meine Seufzer, meine Tränen

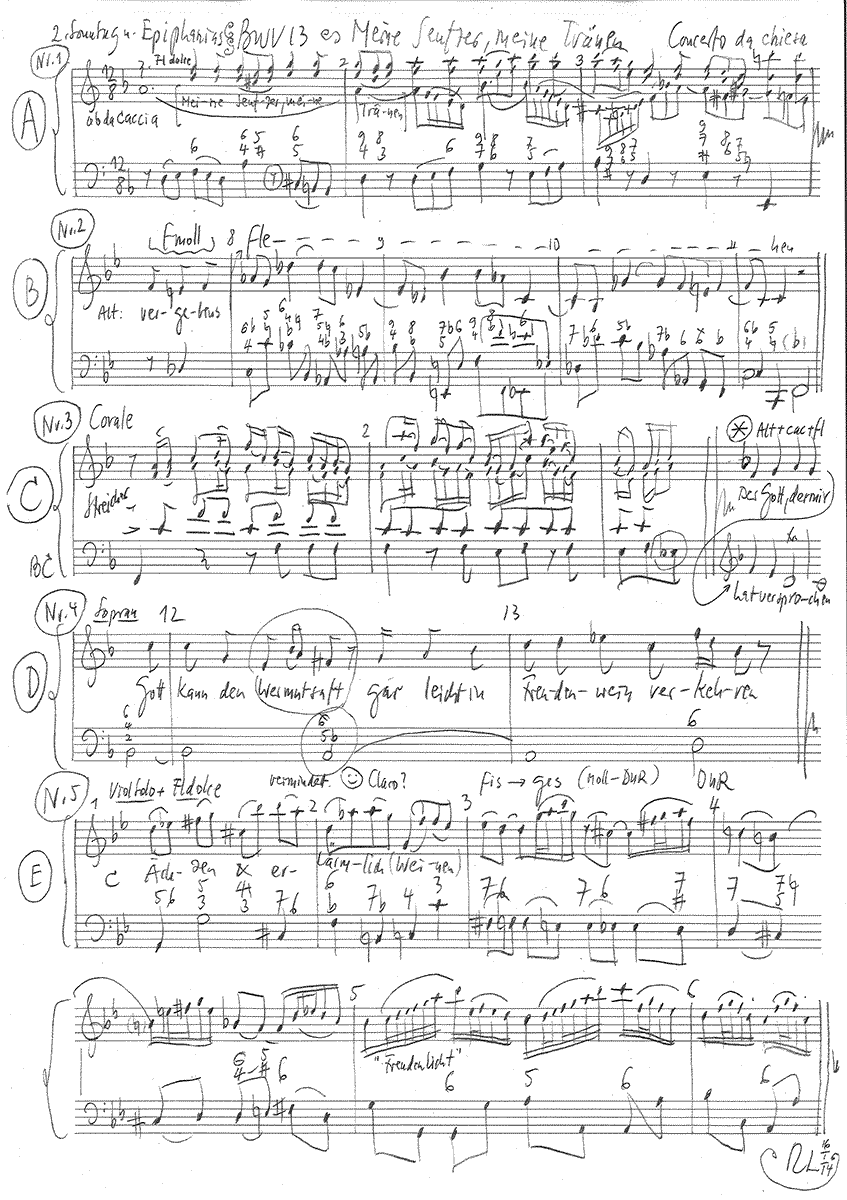

BWV 013 // For the Second Sunday after Epiphany

(Of my sighing, of my crying) for soprano, alto, tenor and bas, flauto dolce I+II, oboe da caccia, bassoon, strings and basso continuo

Cantata BWV 13 “Meine Seufzer, meine Tränen” (Of my sighing, of my crying), marked in hand on the score as a “Concerto da Chiesa”, is a work revealing and eliciting a deep personal involvement. Were the text not derived from the devotional works of Georg Christian Lehms – and clearly written for general purposes – the cantata could be mistaken for a votive composition undertaken for personal reasons or for a commissioned funeral composition (in the style of cantata 157). Perhaps, then, we may regard it as a cantata of consolation with an unusually personal character – and one from which not only the Leipzig congregation of 1726 benefited. Whatever the exact circumstances of its origin, however, the soloistic tendencies and distinctive oration typical of Bach’s third cantata cycle certainly find moving expression in this work.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen

Viola

Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Recorder/Flute

Annina Stahlberger, Teresa Hackel

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Stefan Stirnemann

Recording & editing

Recording date

01/17/2014

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 2, 4, 5

Georg Christian Lehms, 1711

Text No. 3

Johann Heermann, 1636

Text No. 6

Paul Fleming, 1642

First performance

Second Sunday after Epiphany,

20 January 1726

In-depth analysis

The opening aria, despite its densely woven score, remains light and transparent in sound. Indeed, the solo part is a shining example of how baroque affect, in its strict sense of evoking a distinct emotion, can nonetheless sound noble and natural when in the hands of a master – the music here is never sermonising, but authentic and new throughout. Composed in the style of a funereal pastorale, the voice is underscored by exquisite instrumental writing a tentative continuo part overlaid by the sighing of recorders whose thin sound is warmed by the “voice of love”, the oboe d’amore. With the delicate timbres of these woodwind instruments, not even the hefty dissonances sound false or hard, but portray with gentle intensity a lasting image of sorrow: a lonely old widower, in a darkened room, whose pains of the day burden the breast at night. This mood is then sustained by the halting gestures and expressive pauses of the alto recitative – a handwringing “entreaty” reflecting both hopeful impatience and resigned defeat: will the salvation visible “from afar” arrive in good time?

The following chorale setting sheds light on this darkness in a most liberating way: the alto commences singing, and the comforting change of mood does not appear a mere wonder, but rather the result of the faithful reflection described in the text. Here, the whole power of the Protestant chorale is evident in the modest joy of the music. Moreover, the comfort it expresses also answers the question of the chorale’s meaning to Bach, who musically contemplates the Cartesian problem of the possibility of knowledge and the certainty of good, thereby presenting his own “meditations on the metaphysical”: because God, in the Bible-word of the chorale, has given his promise, he must, ultimately and by the strength of active faith, be benevolent ! The theologically well-versed Bach thus musically fulfilled Luther’s precept of justification by faith – indeed, the highly artistic, yet welcoming music wonderfully fills the heart with joy.

It speaks for the sensitivity and life experience of the librettist and composer that the following soprano recitative opens with a new line of enquiry (Confutatio). Nonetheless, raw anxiety still holds sway: is my “cup of woe” already “overflowing”? Have I already grown “cold” and thus incapable of receiving comfort? Indeed, it costs the fearful vocalist audible strength to suppress the “songs of sorrow” and embrace the inspiring image of the “wormwood’s gall” being transformed into “wine of rapture”.

Listeners expecting a down-to-earth setting of relief to follow, however, are mistaken. Rather, the bass solo (“moaning and most piteous weeping”) presents a cleansing exploration of human fears and the inadequacy of our strategies to overcome them. With its shimmering unison writing for recorders and solo violin in addition to the ever-sighing character of the melody, the aria draws a depressing picture of futile complaint, but one that is sensitively caricatured with benevolent intent. The path to a peaceful worldview is thus presented as a lifelong struggle, but one that will be rewarded, as suggested by the moments of joy and in the equilibrium of the middle section.

The closing chorale is based on the last verse of the hymn “In allen meinen Taten” by the great baroque poet, traveller and doctor Paul Fleming. Although not envisioned in Lehms’s original text, this verse, reflecting Fleming’s unfaltering trust in God, rounds out the cantata on an introspective note.

Libretto

1. Arie (Tenor)

Meine Seufzer, meine Tränen

können nicht zu zählen sein.

Wenn sich täglich Wehmut findet

und der Jammer nicht verschwindet,

ach! so muss uns diese Pein

schon den Weg zum Tode bahnen.

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

Mein liebster Gott läßt mich annoch

vergebens rufen

und mir in meinem Weinen

noch keinen Trost erscheinen.

Die Stunde lässet sich zwar wohl von ferne sehen,

allein ich muß doch noch vergebens flehen.

3. Choral

Der Gott, der mir hat versprochen

seinen Beistand jederzeit,

der läßt sich vergebens suchen

itzt in meiner Traurigkeit.

Ach! Will er denn für und für

grausam zürnen über mir,

kann und will er sich der Armen

itzt nicht wie vorhin erbarmen?

4. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Mein Kummer nimmet zu

und raubt mir alle Ruh.

Mein Jammerkrug ist ganz mit Tränen angefüllet,

und diese Not wird nicht gestillet,

so mich ganz unempfindlich macht.

Der Sorgen Kummernacht

drückt mein beklemmtes Herz darnieder,

drum sing ich lauter Jammerlieder.

Doch, Seele, nein,

sei nur getrost in deiner Pein:

Gott kann den Wermutsaft gar leicht in Freudenwein verkehren

und dir alsdenn viel tausend Lust gewähren.

5. Arie (Bass)

Ächzen und erbärmlich Weinen

hilft der Sorgen Krankheit nicht.

Aber wer gen Himmel siehet

und sich da um Trost bemühet,

dem kann leicht ein Freudenlicht

in der Trauerbrust erscheinen.

6. Choral

So sei nun, Seele, deine

und traue dem alleine,

der dich erschaffen hat.

Es gehe, wie es gehe,

dein Vater in der Höhe,

der weiss zu allen Sachen Rat.

Stefan Stirnemann

Of weeping and of the soul that is theirs

A fictional conversation between Seneca and Paul with insight value: the final chorale of the cantata “Meine Seufzer, meine Tränen” (My Sighs, My Tears) moves at the interface between Stoic philosophy and Christian assurance of salvation.

Imagine that there are three people standing in the church of Trogen next to the one who is reciting this reflection. I show and name them to you, pay attention; by naming them, they become visible. First on the left is a stocky man in distinguished Roman dress, white hands, wearing a ring on his right ring finger: a sign of power. It is Seneca, the Stoic philosopher. What is his power? He is the educator and advisor of the still youthful Emperor Nero, and together with General Burrus, the commander of the Praetorians, he leads the Roman Empire. Seneca, wealthy in his own right, repeatedly accepts allowances from the imperial house. Powerful and rich – can a philosopher be? Seneca’s features are not philosophically furrowed and austere. He is reproached that his teachings do not fit his life. But as he stands among us now, he convinces with his strength and calmness. Seneca is still the best-known Stoic.

To his left, about the same height but gaunt, stands Paul the Apostle. He looks like you always imagined him – so you recognise him without a long description: experienced, confidence-inspiring; his strong chin shows zeal.

The third person stays shyly in the background, I’ll name him later.

Seneca, the non-Christian philosopher, and Paul are contemporaries, they live in the first century of our era. I have called them to Trogen so that they can give us brief and lasting information in a conversation. With this information I want to contribute to the interpretation of the final chorale of our cantata:

“So now, soul

Be thine and trust in him alone

who created you.

Let it be as it may,

Thy father on high,

Who knows counsel in all things.”

The verse is by the poet Paul Fleming, from his poem “In all my deeds I leave counsel to the Most High”. It’s in the church hymnal. The thing about this stanza is that it poses a question. Does “So now, soul, be thine” fit the continuation “and trust in him alone who created thee”? Wilhelm Müller, the poet of “Winterreise” and “Schönen Müllerin”, was puzzled here. When he published Fleming’s poems in 1822, he remarked: “So now, soul, be thine” – “perhaps: his i.e. God’s”. Isn’t Wilhelm Müller right? We all have in our ears what Isaiah says: “But now saith the Lord that created thee, Jacob that formed thee, Israel; Fear not, for I will deliver thee: I will call thee by thy name; thou art mine.” It is not written, “Thine art thou!” As I quote Isaiah there, do you see Paul nodding in agreement? Seneca, on the other hand, listens attentively but does not stir.

To get the conversation going, I briefly tell you about my brother. When my brother was a six-year-old boy, one day he suddenly had to cry. Asked why, he said, “It occurred to me that I must die, and yet I always wanted to live.” Dying – that’s the key word. Seneca, tell us something about weeping and dying.

Seneca says, “Do you wonder about weeping? Nature willed that man should be born weeping. Don’t you see what kind of life she promised us with that? Quid est homo? What is man? A vessel that is destroyed by even a slight blow. A weak body, helpless and dependent on outside help, at the mercy of every fate. We are not running out of reasons to cry. Rather, we run out of tears.

We are allowed to cry over the death of a close person, but in a philosophical attitude, i.e. with moderation and dignity. It would be foolish to cry over the fact that one has to die oneself. A child, of course, may cry about it.”

Good, Seneca. But why, I ask, is man at the mercy of fate and dying? Seneca says: “The world is arranged in this way. It is ordered in opposites, and the ultimate opposition is that of coming into being and passing away. When you are born, you are about to die. And when you die and whether your life succeeds, there is no certainty about that. That’s the way it is, and even the gods can’t change it. So why cry?” Seneca is silent.

Paul, as with Isaiah, also nodded to Seneca’s words. Just then, however, he shook his head when Seneca mentioned the gods. Paul said, “Yes, the world is subject to corruption, the form of this world is passing away. The whole creation groans and is in anxious expectation. Whence impermanence and death? They are not simply doom. They came with Adam’s disobedience. With Christ, life is in the world. And yet we Christians also groan; we wait for full redemption, for God to accept us in the Son’s stead, for us to become His own.” Paul is silent.

Redemption, you say, Paul: that is a consolation. Seneca, knowest thou also an effectual help? Seneca says: “Go within yourself, go within yourself. There you will find a holy spirit, a sacer spiritus. This is the reason, the ratio, which rules in the whole cosmos. Take time for yourself and think. Know yourself, know the essence of things. Examine what is possible for you, and think of all that is possible in the world. Think ahead: Nothing will then hit you unexpectedly, you are composed, you are safe in all uncertainty. Trusting in yourself, you are active and do your duty. Trusting in yourself, you submit to the order of things and welcome every fate. Even a life, however short, is enough for you.” – “The order of things,” I say, “you can also call it God. Trusting in reason, you trust God, the Most High, and follow Him, not because you must, but, rightly seen, because you will. Let that be your attitude: Dwell in the body and in the world as one who will depart: Tamquam migraturus habita! Keep your distance. So you are no one’s property, you are yourself, you are free, you are yours.”

Here Paul says, and perhaps a regret resonates, “I cannot trust the inner man and his reason so much. Dwell as one who is going away, you say, Seneca? I like that. I say the same thing: have the things of the world as if you did not have them. Thus you keep your distance and free yourself for the effective consolation, the redemption. But salvation does not come from you.” Paul is silent.

Seneca, I say, your consolation is thinking. Will you give us an example? Seneca says: “I choose death as an example. Death means non-being. What that is, I know. I experienced it before I was born. When I think back to that non-being, I find nothing threatening. So the non-being of death need not and cannot frighten me. With this thought I comforted myself when I had a severe asthma attack.”

How did Seneca, the Stoic, die? He was accused of taking part in a conspiracy against Nero. The emperor himself sent him orders to take his own life. Paul probably also died in Rome under Nero, as a martyr. The two agree in some thoughts, which is surprising. They did not know each other; an exchange of letters between them has been handed down, but it is an invention.

As I say this, Seneca and Paul fade away, two windows of the church in Trogen open quietly, and they disappear in a wintry breeze. And the third person in the background? – Later!

“So now, soul, be yours”: to be his own – that is a formula and maxim of Stoic philosophy. Seneca gave the most effective expression to this philosophy. How does Seneca come into the Bach cantata?

The poet Paul Fleming lived in a time when Latin was the language of science and education. Even in Bach’s day, it was the job of the Thomaskantor to teach four hours of Latin per week. Bach, the Thomaskantor, had himself substituted. Fleming, a hundred years before Bach and a pupil in Leipzig, is not only one of the greatest German poets of the 17th century, he also wrote in Latin. In a Latin poem about fate, he writes: “He who is his own holds the highest good.” That sounds like Seneca right down to the Latin wording. Why was Stoic philosophy so influential at the time that in retrospect we speak of the Neo-Stoicism of the time with a sharp hissing foreign word? The answer must surely be: In the unheard-of and cruel uncertainty of the Thirty Years’ War, people sought security and composure in themselves.

And what about us? 2014 is the beginning of a year in which we remember another Thirty Years’ War. It began a hundred years ago, lasted until 1945 and still determines our lives and thoughts today.

And now the time has come for the third man to make his appearance in Trogen. But he does not appear, like Seneca and Paul, he remains modestly in the background, I speak for him.

It is Cato Bontjes van Beek, a young German with a Dutch name. Cato, she believed, had no life’s work to show for it: “It’s a pity I leave nothing in the world but the memory of myself,” she wrote in a farewell letter to her mother. She was murdered by the Nazis with a guillotine in the accursed year of 1943, aged twenty-two.

In a photograph, Cato’s hands catch my eye. They are strong and soulful, they can shape something. Cato’s father was a famous ceramist and she wanted to apprentice with him. Her whole family was artistically gifted; the painter Otto Modersohn was an uncle by marriage. Cato has an open, soft face that is beautiful in its frankness. Something special are her radiant eyes. When a Ukrainian woman, deported to Germany for forced labour, showed her a photograph of her family, she cried with her.

Cato was sentenced to death because she joined a resistance group; the group is known as “The Red Chapel”. Cato was not a member for long and only collaborated on a leaflet. This was considered by the Nazi murderers as aiding and abetting high treason.

When she had to wait for her execution, she read an essay by Schopenhauer: “On Death and its Relationship to the Indestructibility of Our Being Itself”. Schopenhauer presents Seneca’s consoling thought, namely that the non-being of death is no more terrible than the non-being before birth. Cato wrote to her friend, also condemned to death: “I do not need to draw strength from a definition of death. (…) We can now judge such a thing, for we now learn it whether it is true or not.”

The logic of philosophy did not appeal to Cato.

To her mother she wrote: “A few nights ago I dreamt I heard it (meaning: the Matthew Passion). And it was wonderful. Surely it is glorious that these divine things belong to us all and that a mortal man was able to create them.”

So perhaps Cato heard in a dream the final chorale of our cantata, “My sighs, my tears”. It sounds twice in the St Matthew Passion: “It is I, I should atone” and “Who hath so smitten thee”.

“So be now, soul, thine!” One can split the stanza into a Stoic, philosophical part and a Christian, Pauline part. The basic question is: What is my own contribution to that which ultimately helps me, which redeems me? If one draws the boundaries of the terms hard, Seneca with his Stoic self-determination contradicts the Apostle Paul. But the poet Fleming composed the stanza as a unity, and Bach, the mortal man who was able to create divine things for us, composed it as a unity. I am in favour of hearing them as a unity, I am in favour of having Seneca sing along in our Bach cantata. You have already heard him in earlier cantatas, and you will hear him out in more cantatas from now on.

Understand him correctly, be yours.

Literature

Barbara Neymeyr, Das autonome Subjekt in der Auseinandersetzung mit Fatum und Fortuna. Zum stoischen Ethos in Paul Flemings Sonett An sich, and Jochen Schmidt, Eine stoische meditatio mortis: Paul Flemings Grabschrift auf sich selbst, in: Barbara Neymeyr, Jochen Schmidt, Bernhard Zimmermann (eds.), Stoicism in European Philosophy, Literature, Art and Politics, Art and Politics, Volume 2, Berlin, New York 2008.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).