Gleich wie der Regen

BWV 018 // For Sexagesimae

(Just as the showers) for soprano, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, recorder I+II, bassoon, viola I-IV and continuo.

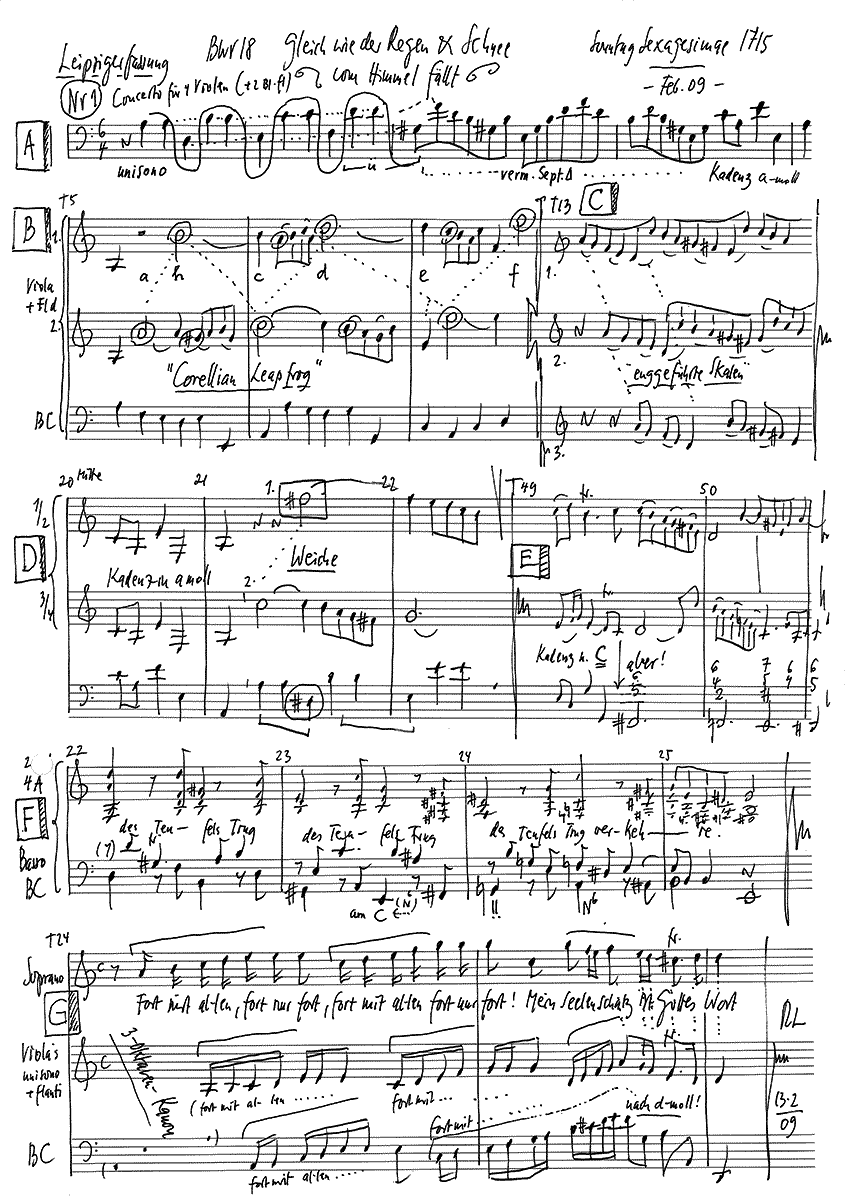

The cantata “Gleich wie der Regen und Schnee vom Himmel fällt” (Just as the showers and snow from heaven fall) is undoubtedly unique in Bach’s oeuvre. While its libretto and form are distinctive in themselves – with a long opening dictum referencing the parable of the sower, a single aria and an extensive litany as a middle movement – the instrumentation for just four violas and continuo truly sets the work apart. Even when Bach re-performed the cantata in Leipzig around 1724, he did not “correct” his Weimar instrumentation to create a typical string group with violins, but instead added two recorders, there by only slightly brightening the timbre.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Leonie Gloor, Guro Hjemli, Jennifer Rudin

Alto

Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Damaris Nussbaumer, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Renate Steinmann, Martina Bischof, Joanna Bilger

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Bassoon

Nikolaus Broda

Recorder/Flute

Armelle Plantier, Gaëlle Volet

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Hans Jecklin

Recording & editing

Recording date

02/13/2009

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 2

Quote from Isaiah 55:10–11

Text No. 3, 4

Erdmann Neumeister (1671–1756)

Text No. 5

Lazarus Spengler, 1524

First performance

Sexagesima Sunday,

24 February 1715, Weimar

In-depth analysis

Because the complex bible verse did not lend itself easily to a choral setting, Bach opened the work with a sinfonia, whose sound bears a striking resemblance to the 6th Brandenburg Concerto. Despite its wan F minor tonality and somewhat currish ritornello, the movement exults in the warm timbre of the violas (and recorders), especially in the elaborate solo passages. In the ensuing bass recitative, Bach breathes life into the rather dry gospel through word painting (“give the earth moisture”) and the inclusion of aria-like passages. That these words have indeed fallen on fertile ground is revealed in the ensuing recitative: carried by an expressive string accompaniment, the tenor moves to open his heart so that the godly seed may prosper there. This, however, is just the beginning of one of the most formally extraordinary movements in Bach’s cantata oeuvre. Featuring constantly shifting tempi, instrumentation and melodic patterns, the recitative evolves into a full-scale litany that knows no liturgical constraints, but is explored in all its textual nuances. Underscored by a turbulent continuo, the petitions of the soprano and the four-part response make for extraordinary drama: behind the traditional form of the cantata, a profoundly modern music has taken shape. With his interpretation, Bach unveils the explosive power inherent in the concept of a “sacred cantata instead of church music” introduced by his librettist Erdmann Neumeister around 1700. It also explains the vehement opposition traditionalist theologians took to such blatantly operatic compositional forms.

After this show of strength, a necessary softening of affect is delivered by the short soprano aria “My soul’s true treasure is God’s word”. While the unison writing for four violas may somewhat amuse connoisseurs of viola jokes, Bach’s intention was surely to evoke a reverent and composed mood that manages to extract emotion even from the rigorous text with its message of worldly denial. The closing chorale – a verse from the well-known hymn “Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt” – provides a congregational response to the parable of the sower in which the somewhat dark and fragile timbre of the violas and recorders befits the movement’s mood of inherent “sin and shame”.

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Gleich wie der Regen und Schnee

vom Himmel fällt

und nicht wieder dahin kommet,

sondern feuchtet

die Erde und macht sie fruchtbar

und wachsend,

dass sie gibt Samen zu säen

und Brot zu essen:

also soll das Wort,

so aus meinem Munde gehet,

auch sein; es soll nicht wieder

zu mir leer kommen,

sondern tun, das mir gefället,

und soll ihm gelingen,

dazu ich’s sende.

3. Rezitativ (Tenor, Bass) und Chor

Mein Gott, hier wird mein Herze sein:

ich öffne dir’s in meines Jesu Namen;

so streue deinen Samen

als in ein gutes Land hinein.

Mein Gott, hier wird mein Herze sein:

lass solches Frucht und hundertfältig bringen.

O Herr, Herr, hilf! O Herr, lass wohlgelingen!

(chor)

Du wollest deinen Geist und Kraft zum Worte geben.

Erhör uns, lieber Herre Gott!

(bass)

Nur wehre, treuer Vater, wehre,

dass mich und keinen Christen nicht

des Teufels Trug verkehre.

Sein Sinn ist ganz dahin gericht’,

uns deines Wortes zu berauben

mit aller Seligkeit.

(chor)

Den Satan unter unsre Füsse treten.

Erhör uns, lieber Herre Gott!

(tenor)

Ach! Viel verleugnen Wort und Glauben

und fallen ab wie faules Obst,

wenn sie Verfolgung sollen leiden.

So stürzen sie in ewig Herzeleid,

da sie ein zeitlich Weh vermeiden.

(chor)

Und uns für des Türken und des Papsts

grausamen Mord und Lästerungen,

Wüten und Toben väterlich behüten.

Erhör uns, lieber Herre Gott!

(bass)

Ein andrer sorgt nur für den Bauch;

inzwischen wird der Seele ganz vergessen;

der Mammon auch

hat vieler Herz besessen.

So kann das Wort zu keiner Kraft gelangen.

Und wieviel Seelen hält

die Wollust nicht gefangen?

So sehr verführet sie die Welt,

die Welt, die ihnen muss

anstatt des Himmels stehen,

darüber sie vom Himmel irregehen.

(chor)

Alle Irrige und Verführte wiederbringen.

Erhör uns, lieber Herre Gott!

4. Arie (Sopran)

Mein Seelenschatz ist Gottes Wort;

ausser dem sind alle Schätze

solche Netze,

welche Welt und Satan stricken,

schnöde Seelen zu berükken.

Fort mit allen, fort, nur fort!

Mein Seelenschatz ist Gottes Wort.

5. Choral

Ich bitt, o Herr, aus Herzens Grund,

du wollst nicht von mir nehmen

dein heilges Wort aus meinem Mund;

so wird mich nicht beschämen

mein’ Sünd und Schuld, denn in dein’ Huld

setz ich all mein Vertrauen:

Wer sich nur fest darauf verlässt,

der wird den Tod nicht schauen.

Hans Jecklin

“Trogen – Persepolis – Isfahan – and back to Bach”.

Thoughts on a global spirituality.

When I attended a performance of this great cantata cycle here in the church in Trogen last September, in order to prepare myself inwardly for this evening, I was quite unexpectedly captivated by the large choral painting that closes off the church space. It is the representation of the four continents by groups of people from Asia, Europe, America and Africa that attracted and irritated me in equal measure. The different origins of the people depicted are imaginatively, if somewhat clumsily, recreated; in keeping with the countries they represent, they are endowed with foreign features, exotic clothing and extravagant headdresses. They all look up in a reverent attitude to the Christ hovering above them, who points with his left hand to a light half-hidden by a grey cloud, probably symbolising the presence of the divine, and with his right hand to a scroll turned towards the people: “Turn to me, all the ends of the earth, and you will be helped, for I am God and no one else,” it says, referring to chapter 45, verse 22 of the Book of Isaiah.

At first I perceived the painting as an expression of the cosmopolitanism of the Zellweger family dynasty; their worldwide trade relations have shaped this place, and the stately church in which we find ourselves this evening is also due to their generosity. But then the imperative appeal to the faithful aroused my resistance: even more than the all-too-naïve view of globalisation, not yet at all aware of its dark sides, I was irritated by the idea of the globalisation of Christianity across all differences of cultures. At the time, I said to myself that I wanted to come back to this in this reflection.

Six weeks later we travelled to Iran. In the first few days we visited Persepolis, one of the magnificent residences of the Persian royal dynasty of the Achaemenids, who ruled over a world empire unparalleled until then between the 7th and 5th centuries BC. The large relief at the entrance to the main hall of the residence depicts the tribute procession of deputies from the many peoples of the empire as they file past the king at the New Year’s festival. Their respective affiliations can be recognised by the costumes they wear and the gifts they bring with them. The people depicted appear upright and self-confident, not at all like subjugated slaves.

A symbol previously unknown to us adorns the centre of the relief and is repeated above many archways, doorways and window openings: a bird with outstretched, feathered wings and tail feathers, but with a human head and upper body. When we visited the sanctuaries of the Zorastrians in Yazd a few days later, we found the explanation: the bird-man stands for the almighty god Ahura Mazda, whose traces lead back to the Aryan, Indo-Iranian nomadic tribes of Central Asia. From their religion and way of life based on the cult of fire and magic, both Hinduism, founded on the Vedas, and Zoroastrianism, founded by the prophet Zarathustra, may have developed some 3000 to 4000 years ago.

Finally, in Isfahan, we were unexpectedly led into a quiet courtyard: Here, in this small shrine with its particularly intimate atmosphere, was the tomb of Isaiah, we were told with great astonishment. No one could tell us more about how the Jewish prophet found his way to Isfahan. Isaiah in Isfahan?

Back in Switzerland, I found the commentary on the choral painting1 that had arrived in the meantime. To my not insignificant astonishment, I discovered immediately on first perusal of the picture description that the man in the pointed hat and shepherd’s shirt – on the far left in the Asian group – who points so humbly with his left hand to the divine light, represents Cyrus II, King of the Achaemenids: Kyros II, founder of the first world empire in human history. The Achaemenid empire reached the Indus in the east; in the west it included Babylon, Palestine and temporarily Egypt, and in the north it included Asia Minor – today’s Turkey – as well as parts of the Caucasus and Central Asia. Cyrus must have been a cosmopolitan and incomparably tolerant ruler for his time. The constitution he issued around 530 B.C., from which I quote two passages here, is considered today to be probably the first declaration of human rights:

“(…) I proclaim that as long as I am alive and Mazda grants me power, I will honour and respect the religion, customs and culture of the countries of which I am king, nor will I allow my leaders and people under my power to despise or insult the religion, customs and culture of my kingdom or of other countries. As long as I rule with the blessing of Mazda, I will not allow men and women to be traded as slaves. Slavery must be abolished throughout the world. I demand of Mazda that he help me succeed in my tasks towards the peoples of Persia, Babylon and the countries in the four directions.”

But how on earth does Cyrus II find his way into the choir of Trogen Church? Because the verse shown in the choir painting comes from that part of the Book of Isaiah – chapters 40-55 – in which Cyrus II is central as God’s chosen liberator of the Jews from Babylonian captivity. “I have formed you and made you a covenant mediator for the human race, the light of the nations”, his God says to him. He addresses him as “my shepherd”. Hence the depiction in a shepherd’s shirt, while the pointed cap recalls the head covering of the pointed-hatted Saks on the relief in Persepolis.

The second surprise that the commentary had in store for me was the view that this part of the Book of Isaiah is not attributed to the Jewish prophet of prophecy, but to Deutero-Isaiah (a second Isaiah), who probably lived 200 years later, precisely at the time of the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus II, which enabled the Jews living in captivity to Nabonid to return to Jerusalem. So we visited the tomb of this second Isaiah in Isfahan?

It always fills me with great wonder when such unexpected connections reveal themselves, when elements – as if ordered by an invisible hand – come together and circles seem to close.

This second part of the Book of Isaiah speaks of the wisdom and greatness of Cyrus II as a ruler and commander. Initially, the verses are clearly marked by the tolerant spirit of Ahura Mazda; however, especially towards the end, the commanding, punishing and avenging character of Yahweh, the Israelite tribal god of the First Testament, takes over. This transition seems to me to be an apt example of the change of images of God through cultures and in the course of time.

Let us imagine how in a few minutes, starting from the choir painting in the church of Trogen, we have touched the Aryan tribal religions from which the Vedas and Zoroastrianism unfolded, how we have found our way almost without transition to the words of the Jewish God whose call to all the ends of the earth to turn to him is conveyed in the painting before us through Christ. when it is written in the 1st Book of Moses “God created man in his image”, today we must rather imagine that man created God in his image and built bridges to the inexplicable in the form of myths; bridges that gradually, and ever anew, with the evolution of consciousness, turn out to be superstitions. To grow with them here: therein lies a great challenge to the religions, a key also to more peace in this world.

If we consider the changes in the images of God through the cultures and their history, it quickly becomes clear: their background can only be a common one. The Absolute, the primordial ground of all being, is not divisible. The mystics of all religions have probably discovered their own approaches to the primordial ground; and no matter how much these approaches differ in the world of their images and ideas: In their essence, the transition from multiplicity to unity, they all correspond to each other. It is about stillness, about presence. when for a moment nothing separates us from the present – no future, no past – something within us lights up. A feeling of happiness, a oneness with life. We have all experienced this, experience it again and again: in moments of being in nature, in arriving at the top of a mountain, in harmony with people close to us, even in the long-awaited first bite of that so delicious chocolate cake. It is the nature of our innermost being that is able to reach us then; because our attention, perhaps only for a moment, is not absorbed by the fabric of involuntary thinking and feeling. Only: if we do not recognise and take this fleeting happiness as our own in each case, but attach it to external circumstances, it becomes the object of our longing for eternal repetition on the outside. If, however, we take a different path and pay attention to perceiving and accepting such moments of happiness as the illumination of our innermost being, we will gradually find ourselves in an ever deeper upliftment: in a boundless, unconditional love that means us completely.

Is not this upliftment the place of our deepest longing; to be loved just as we are? Haven’t we always meant this upliftment, this being loved without conditions or limits, when we strived, often with all our strength, to fulfil expectations, to be successful and admirable in the eyes of others? However, as long as we attach our upliftedness, even our securities, to external phenomena, which by their nature are transient, disappointments are inevitable. They will cause us pain until we recognise and accept them – often only in retrospect – as signposts to the essential. The more deeply we are rooted in our own, the less we will want to tie ethical thinking and action to external commandments and expectations; our ethical orientation arises naturally from a deep inner knowledge of what is right for us and for others.

If we look at the world from this perspective, we perceive its phenomena as all connected to all. Globalisation reveals itself as an expansion of human consciousness in the sense of evolution; solidarity and co-responsibility for the whole of which we are a part is an indispensable part. For we know: We can only do well if the whole does well.

And this brings me to today’s cantata. The fact that the text of the first recitative, which characterises the whole cantata, also comes from this second Isaiah, which I now call the Persian one, is another aspect of the little miracle – or chain of coincidences – that accompanied me in the preparation of this reflection.

“Just as rain and snow fall from heaven and do not return, but moisten the earth and make it fertile and grow, so that it gives seed to sow and bread to eat, so shall the word that comes out of my mouth be; it shall not return to me empty, but it shall do what I please, and it shall prosper when I send it.”

According to Isaiah’s text, it is God who speaks here. From the perspective of being lifted up in the One, I dare to say: God cannot be anyone else. It is me, and it is my responsibility to speak from the heart in such a way that the seed sprouts, that my words bear fruit. we must no longer delegate this responsibility to an external God; that is not appropriate for our time. I think of Meister Eckhart: “Here God’s ground is my ground and my ground God’s ground. Here I live from my own, as God lives from his own,” he said with unheard-of boldness for his time (and even more aptly elsewhere: “Some simple-minded people think they should see God as if he stood there and they here. This is not so: God and I, we are one.”). It is up to us to take responsibility for a language that bears fruit; we cannot delegate it. For it is by thinking, speaking and acting from the innermost upliftment that we change the world.

The devil, the Pope, the Turks, Mammon, lust and gluttony are nothing other than our own inner cabinet of shadows; they too ultimately belong to our own responsibility. if we take them to our heart, to a heart nourished from the primordial ground, the shadows lose their demonic form; they develop into helpful qualities that enrich our personality.

In this sense, I think it would not be a good recipe to sing with Bach “Hear us, dear Lord God!” and to “tread Satan under our feet” in time. If we do this, Satan will sooner or later confront us on the outside, and we can see what this leads to by looking at current events in the world. Closing our eyes to the dark is no longer a path for today’s human being. we cannot help but – just like our own shadow cabinet – also take the great world theatre to our hearts. This is how we meet the challenges of the change of consciousness: by seeing with our hearts what the world situation has to do with us, what we are doing and what we are bringing about with it, in order to then consider whether we really want it that way.

Back to Bach. All the great works of culture that touch us come from the connection with the primordial ground of all being. And we were able to hear it earlier, in the first performance of the cantata: Bach’s music is also an expression of this primal ground, realised through the uniqueness of Bach’s person, his craft, his creativity. Nothing else is at stake when musicians make music. Mastery of the voice or an instrument and fidelity to the musical text alone are not enough: they are merely prerequisites. Music needs the breath, the pulse of life, and this springs from the same inner source that inspired Bach to write his music.

So we can look forward to the repetition of the cantata. Please, do not now interrupt the fabric that has been created in the room with an applause. The musicians need a few minutes to be ready again. Let their thoughts resonate in the silence. Perhaps the choral painting will show you another dimension? Thank you for listening!

Literature

Heidi Eisenhut, Renate Frohne, Eine Deutung des Chorgemältes der reformierten Kirche Trogen, Kantonsbibliothek Appenzell AR, Trogen o. J.

– Josef Quint (ed.), Meister Eckhart, Deutsche Predigten und Traktate. Vom innersten Grunde, Munich 1955

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).