Schauet doch und sehet, ob irgendein Schmerz sei

BWV 046 // For the Tenth Sunday after Trinity

(Look indeed and see then if there be a grief) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, recorder I+II, oboe da caccia I+II, slide trumpet, strings and basso continuo Scenic intervention on the cantata text: Giovanni Netzer (text), Samuel Streiff (mayor), Martin Ostermeier (prophet)

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Lena Kiepenheuer, Susanne Seitter, Julia Schiwowa, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Katharina Jud, Liliana Lafranchi, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Christian Rathgeber, Sören Richter, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, Tobias Wicky, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Eva Borhi, Christine Baumann, Claire Foltzer

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Bernadette Köbele

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Tromba, Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Flauto dolce

Annina Stahlberger, Teresa Hackel

Oboe da caccia

Carin van Heerden, Anabel Röser

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Jörg Andreas Bötticher

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Michael Maul, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Giovanni Netzer (Text), Martin Ostermeier, Samuel Streiff

Recording & editing

Recording date

18.03.2016

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Lam. 1:12

Text No. 2–5

Poet unknown

Text No. 6

Matthew Meyfart, 1633

First performance

Unknown

In-depth analysis

First performed on 1 August 1723 for the Tenth Sunday after Trinity, cantata BWV 46 is based on the gospel story in which Jesus drives the money changers out of the temple and prophesies the second destruction of Jerusalem (Luke 19:41–48). The latter creates a connection to the Book of Lamentations on the Babylonian siege in the 6th century BCE, writings that the early church had long reinterpreted in a Christian context.

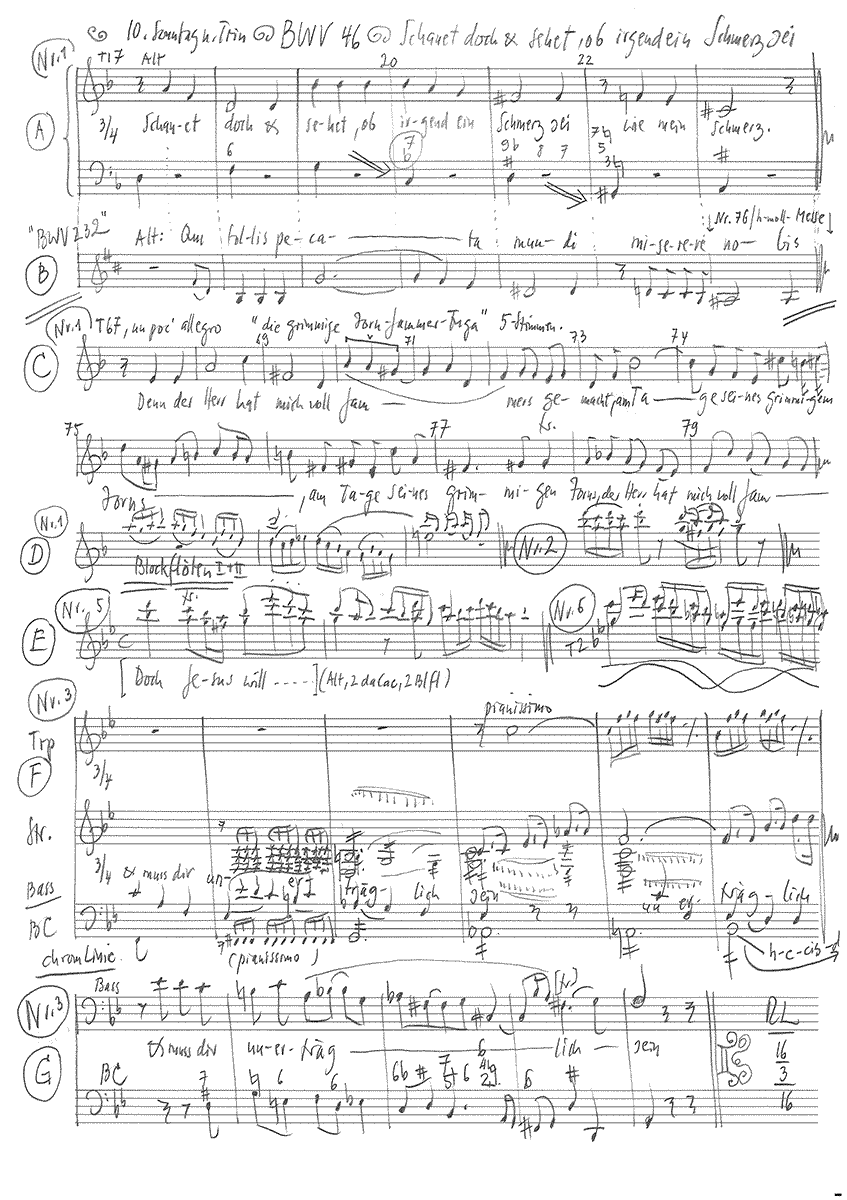

The introductory chorus is thus cast in a tragic vein. Set over a sighing string accompaniment of paired slurs, the circling, alternating figures of two recorders build elegiac phrases suggestive of a musical still life, while the descending minor triad of the successive choral entries evoke an image of bowed heads and rivulets of tears that converge on the harmonically accented word “Schmerz” (grief). At the repeat of the first text phrase, a corno da tirarsi and two oboes da caccia enter to lend the setting the disturbing gravity of a bleak dawn rising over smoking ruins, which the observer is mercilessly forced to endure (“Schauet doch und sehet!” – Look indeed and see then). In this dense lamentation, the recorders permeate the music with such keen severity that listeners can hardly help longing for the end of the first section with its broad cadence and abject tone. The ensuing fugue commences attacca, working with a vividly descriptive theme of austere leaps and drawn-out sighs (“Denn der Herr hat mich voll Jammers gemacht” – For the Lord hath me with sorrow made full). Over the hounded, scampering continuo part, the choir voices build up howling chords that increase in intensity with the successive entries of the instrumentalists up until the obbligato recorders enter – a gruesome vanitas image that culminates in a brutally austere majorkey ending. The fact that Bach reused the slow first section of this movement for the “Qui tollis peccata mundi” of his Mass in B Minor (early Dresden version, 1733) is fitting on a textual level and speaks for his awareness of the setting’s quality when composing the Mass. By replacing the recorders with transverse flutes and removing the accompanying wind parts, Bach lent the music a courtly elegance and transparent sound; due to the attacca transition from the “Domine Deus”, the introductory section was not used.

The tenor recitative sustains this mood with a circulatio figure in the recorder parts that leads stoically through the shifts in key. Through the noble lament and shimmering string lines, the accompagnato setting acquires the tone of a tombeau composition. The cause for lament soon becomes clear: far worse than the city’s physical destruction is the loss of God’s favour and the blaspheming of Christ through disregarding his call for penance. Thus scorned, God cuts the staff asunder, returning at a literal level, too, to the Old Covenant.

Accordingly, the bass aria sketches a grim scene of judgement and retribution, and the fiendishly difficult trumpet part in this movement seems reluctant to sound beautiful; rather, through the lowered final note in the fanfare and grim coloraturas, it issues a warning of impending damnation and absolute power. The singer, with the zeal of a raging prophet, imitates the stormy mood evoked by the dotted figures and repeated notes of the orchestral parts. In Bach’s interpretation, the “überh.uften Sünden” (surfeit of transgressions) in the middle section trigger an almost physical sense of revulsion – that the new Thomascantor had recently promised not to write any operatic, affect-inducing music is barely credible in view of the musical- theological verismo of this setting.

In the following recitative, the fervent, threatening tone continues unabated despite the shift to the gentler alto register. Indeed, it is not just the biblical Jerusalem, but all unrepentant sinners with their mounting burden of sin who will suffer this terrible fate. In the alto aria, the recorders return, this time conveying a tone of child-like, naive trust, to set a scene of a brighter musical language. Because Jesus’ mercy is stronger than the power of Old Testament law, he will “auch bei der Strafe der Frommen Schild und Beistand sein” (even midst the judgment, the righteous’ shield and helper be). Here, the basso continuo remains silent while the oboes da caccia execute a high-register bassett line – a device that in the baroque system of musical rhetoric would typically signify the loss of all stability and support, but in this context conveys freedom from the burden of sin. The dry severity of the setting underscores the gravity of the situation – at issue here is not a noncommittal Sunday sermon, but a pardon at the threshold of the waiting gallows. Nonetheless, the transparent style and laconic, formulaic motifs of the setting make even this reprieve seem temporary: it is likelier that the delinquent will be set free than reformed for life.

In the closing chorale, the wan eddying figures of the recorders, set over a string accompaniment, again evoke a sense of transience. While the earthy, weighty tones of the choir express trust and confidence, the setting opens a window to the fleeting course of destiny, which seems even more haunting in the recorder’s high, wafting figures than in the trumpet’s echoing judgment.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Schauet doch und sehet, ob

irgendein Schmerz sei wie

mein Schmerz, der mich troffen hat.

Denn der Herr hat mich voll Jammers gemacht

am Tage seines grimmigen Zorns.»

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

So klage, du zerstörte Gottesstadt,

du armer Stein- und Aschenhaufen!

Laß ganze Bäche Tränen laufen,

weil dich betroffen hat

ein unersetzlicher Verlust

der allerhöchsten Huld,

so du entbehren mußt

durch deine Schuld.

Du wurdest wie Gomorra zugerichtet,

wiewohl nicht gar vernichtet.

O besser wärest du in Grund zerstört,

als daß man Christi Feind jetzt in dir lästern hört.

Du achtest Jesu Tränen nicht,

so achte nun des Eifers Wasserwogen,

die du selbst über dich gezogen,

da Gott, nach viel Geduld,

den Stab zum Urteil bricht.

3. Arie (Bass)

Dein Wetter zog sich auf von weiten,

doch dessen Strahl bricht endlich ein

und muß dir unerträglich sein,

da überhäufte Sünden

der Rache Blitz entzünden

und dir den Untergang bereiten.

Dein Wetter zog sich auf von weiten,

doch dessen Strahl bricht endlich ein.

4. Rezitativ (Alt)

Doch bildet euch, o Sünder, ja nicht ein,

es sei Jerusalem allein

vor andern Sünden voll gewesen!

Man kann bereits von euch dies Urteil lesen:

Weil ihr euch nicht bessert

und täglich die Sünden vergrößert,

so müsset ihr alle so schrecklich umkommen.

5. Arie (Alt)

Doch Jesus will auch bei der Strafe

der Frommen Schild und Beistand sein,

er sammlet sie als seine Schafe,

als seine Küchlein liebreich ein.

Wenn Wetter der Rache die Sünder belohnen,

hilft er, daß Fromme sicher wohnen

6. Choral

O grosser Gott von Treu,

weil vor dir niemand gilt

als dein Sohn Jesus Christ,

der deinen Zorn gestillt,

so sieh doch an die Wunden sein,

sein Marter, Angst und schwere Pein;

um seinetwillen schone,

uns nicht nach Sünden lohne

Giovanni Netzer

“Comfort is everything”

Introduction

The world is threatened. Fanatical terrorist militias proclaim the end of Western civilisation. War hotspots are becoming the playground of world powers. Climate experts warn of global collapse. Prophecy is booming and plays many roles. Sometimes it appears elegantly as an economic forecast. Sometimes it plays the climate scientist. The invocation of the end times is not new. The Bible names countless prophets who urge people to turn back with terrifying images. They are rarely successful. In the “scenic intervention” to the cantata BWV 46 “Look and see if there is any pain”, a modern mayor and a stubborn concertgoer meet. They embody archetypal archetypes. The mayor reflects the Old Testament king, the concertgoer the archaic prophet with his dark imagery. The basic question remains: How does man confront fear? The Old Testament prophet advises unconditional conversion. J. S. Bach recommends trust in the Son of Man, whose suffering cancels sins. We make do with gigantic security measures and sacrifice freedom for it. Is there a cure for death?

The mayor (Samuel Streiff) and the prophet (Martin Ostermeier) play.

The Mayor (BM) enters the room immediately after the end of the previous item on the programme and addresses the audience. The Prophet (PR) sits in the audience rows.

The Mayor (BM)

Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Jakob Müller. I am the mayor of this city. I must ask you to leave the room quietly and quickly. My authority has received information of a terrorist attack. An attack will be carried out in a church building in the city. We cannot say exactly which place of worship it is. The City Council has therefore decided to evacuate all church premises immediately. I would like to ask you to leave the premises in a well-ordered manner and quickly. There are minibuses and taxis waiting outside the entrance to take you home if you have not arrived in your private car. The underground will remain closed until further notice. The crisis team considers these measures necessary. May I now ask you to leave the room? Please avoid any panic. It is best to start with the back rows so that there is no crowding at the gate.

The Prophet (PR) (standing up).

I am not going to leave. I want to hear the concert to the end.

BM

I’m afraid that’s not possible, sir. May I ask you to leave the room.

PR

I would like to hear the whole concert. I have paid admission.

BM

I understand your anger. Unfortunately, the municipality is not in a position to pay for the cancellation. There’s an act of God involved.

PR

What are the chances of a bomb hitting here? (turns to the audience) Do any of you have explosives with you? Could you possibly wait until the end of the concert before you bomb it?

BM

Can I ask you to refrain from such jokes?

PR

How many churches are there in this city?

BM

An estimated 140 sacred buildings, counting the parish centres.

PR

So the chance of an attack is less than one per cent. I’ll take that risk. I’ll stay. Keep the musicians playing. Please.

BM

I can’t take that responsibility. They have to go.

PR

I am staying. You have no responsibility for my life. They did not give it to me. They will not take it from me. I’ll stay and listen to the concert.

BM (thinking).

The city will reimburse your entrance fee. As an exception. To all other concert-goers too, of course.

PR

The city will reimburse my concert attendance with my tax money? So I pay admission twice for half the music? I will not support this insanity. I will stay.

BM

My Lord, I will have to have you removed. In the interest of all present, I ask you one last time. Leave voluntarily.

PR

I am not afraid. I will stay. And all the other visitors stay too. No one moves, as you can see.

BM

Then the police will evacuate the room.

PR

You mean storm it? Can you justify such a large police contingent?

BM

The safety of the residents is paramount. I will have the hall cleared.

(reaches for the phone)

PR

And then? When the hall has been cleared and everyone is sitting at home? What then? Will curfew be imposed? For two days? For a fortnight?

BM

If security demands it: yes.

PR

That’s just the beginning then. The city will increase its security measures. There will be patrols in the metro stations. Club corridors will be double-staffed. Well-trained box-closers will guard the theatres. In one hand, the theatre programme. In the other, a pistol. Airports will be turned into fortresses. Air fares will rise. Corporate CEOs will continue to travel. The poor will stay at home. How will you protect the city? The banking districts? The government buildings? The synagogues? The asylum seekers’ homes? Hasn’t the city council just announced a new round of savings and decimated the police force?

BM

Security has top priority. If necessary, taxes must be raised. To save life and limb.

PR

All taxes?

BM

All taxes.

PR

The wealthy will change residence. Move to the country and afford their own security guards.

BM

There’s no need for that. After all, there are already permanent patrols and plainclothes officers who …

PR

… who guard the villa districts in the south around the clock. These are personnel who have been taken away from schools and asylum seekers’ homes.

BM

The danger must be assessed realistically. If necessary, the army must help. That’s what it’s there for. The army can protect certain neighbourhoods.

PR

They ghettoise the city. In the slums, people are allowed to steal and murder. In the inner city, the military rules. The rich suburbs are fenced off. Even the millionaires’ children no longer play in the garden.

BM

I ask you to leave one last time. I am only doing my duty.

PR

I’ll stay.

BM

We will have you removed.

PR

With police force?

BM

With police force.

PR

Violence to prevent violence?

BM

In your interest.

PR

Violence is not in my interest.

BM

Can’t you see that you are endangering the lives of the other guests? With your stubbornness? You are putting people’s lives at risk.

PR

Am I the assassin now?

BM (silent)

PR

Seriously. Am I the threat?

BM

In a sense, yes.

PR

Then you’ll have to have me taken away. No, you have to shoot me. To save the others.

BM

I will do nothing of the sort. No official will shoot you.

PR

But how are you going to ensure safety? If I endanger the lives of others, you may shoot me.

BM

I will leave now. You can stay. I strongly recommend the other guests to follow my example. (wants to leave)

PR

They will lose the city.

BM

What do you mean by that? How do you mean that? My poll ratings are good. We will win the elections.

PR

I’m not talking politics. I’m talking about doom. You’re going to lose the city to fear. Soon. The poor neighbourhoods in the north will rise up because they are no longer willing to pay for police protection for the rich. There will be burglaries. The police will arm. The army too. Eventually you will shoot into the crowd. First by accident. Then in self-defence. People will storm banks, withdraw money, put it back under the mattresses. At the first blackout, the department stores will be looted. The police will not intervene because the policemen are afraid. And because they themselves are starving.

BM

What is this doom and gloom? Who do you think you are serving with this?

PR

Quacks will appear. False prophets who proclaim disaster and thereby bring about disaster.

BM

You are talking about yourself. You are such a prophet.

PR

I am not a prophet. I have studied history. Everything repeats itself. Sooner or later. Everything goes down, eventually.

BM

How can one live with such an attitude? How can a society believe in its future if the future only promises destruction?

PR

The future is destruction. That is the principle of creation. To live is to die. Death is the essence of life. Fear is useless.

BM

You are a cynic.

PR

No, I grieve as a precaution. But I am not afraid. The city will go down. Every city has gone down so far.

BM

This conversation is getting us nowhere. I am going now.

PR

The captain leaves the sinking ship. First to go. Good!

BM

I am merely setting the good example. (wants to leave)

PR

Shouldn’t the bomb have detonated by now?

BM

I’m going now. Definitely. But tell me one thing: What do you want to achieve with all this theatre?

PR

I just want to hear the music. It’s the best cure for anxiety. You should stay.

BM

You are crazy.

PR

No. Not crazy. In need of comfort. Comfort is everything.

BM

I’m going.

PR

I am staying.

BM

You are going to die. All of you here are going to die.

PR

Aren’t you?

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).