Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht

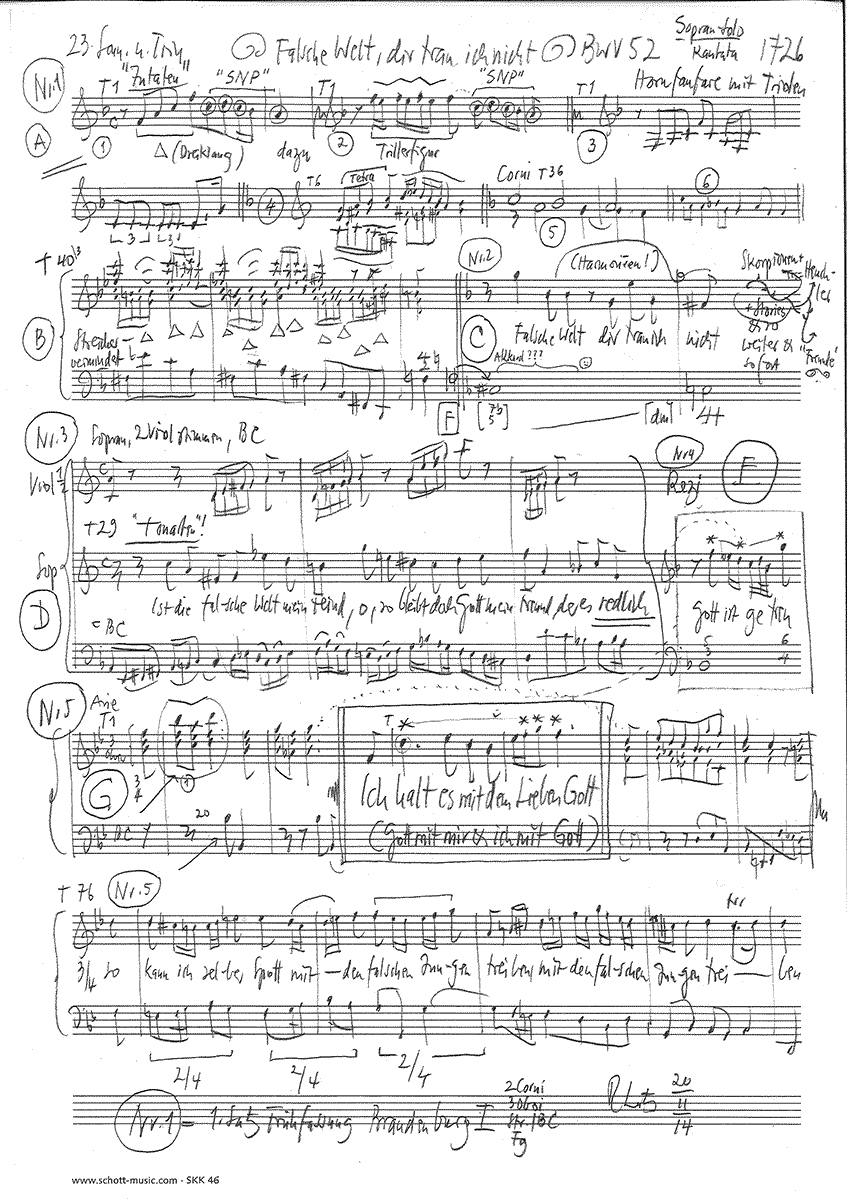

BWV 052 // For the Twenty-third Sunday after Trinity

(Treach’rous world, I trust thee not!) for soprano, vocal ensemble, corno I+II, oboe I-III, bassoon, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Soprano

Miriam Feuersinger

Choir

Alto

Alexandra Rawohl

Tenor

Sören Richter

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Yuko Ishikawa, Elisabeth Kohler, Ildiko Sajgo, Eva Saladin, Olivia Schenkel, Anita Zeller

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Ingo Müller, Julia Bauer

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Corno

Olivier Picon, Ella Vala Armannsdottir

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Jörg Andreas Bötticher

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Michael Guggenheimer

Recording & editing

Recording date

11/21/2014

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 2–5

Poet unknown

Text No. 6

Adam Reusner, 1533

First performance

Twenty-third Sunday after Trinity,

24 November 1726

In-depth analysis

In cantata BWV 52, first performed on the Twenty-third Sunday after Trinity in 1726, it is hard to know whether Bach’s display of splendorous tones serves to illustrate the duplicity of the world, as described in the biblical parable of the tribute penny (Matthew 22), or to counter it with an image of supreme honesty. Whatever the case may be, the opening movement of the first Brandenburg Concerto, which Bach reused here as an introductory sinfonia, imbues the cantata “Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht” (Treacherous world, I trust thee not) with a grandeur that more than compensates for the absence of an opening chorus or an opening tutti aria. And interpreting the majestic horn sounds as a representation of the self-righteously boastful Pharisees confronting Jesus with a trick question requires no stretch of the imagination. With its structure as a solo cantata for one voice, a form not unusual in Bach’s third cantata cycle, the work has elements of a spiritual coming-of-age drama in which a lone soul overcomes fear and the overwhelming forces of the earthly world as trust in God increases.

All the greater, then, is the contrast in the following recitative, which transports the New Testament scene to the present day and employs biblical references to paint a horrifying scene of all-pervasive hypocrisy and deceit. Indeed, among the “Skorpionen” (scorpions) und “Schlangen” (serpents) lurking at every turn, it is the dishonesty of best friends that proves the greatest offence. We cannot know whether Bach and his librettist Christoph Birkmann (who has only recently been identified by researchers) cast a keen eye around the church in this regard, but the notion seems apt for the Baroque city of Leipzig – a trading hub driven by avarice, ambition and no shortage of rancour.

Accordingly, the D-minor aria “Immerhin, wenn ich gleich verstoßen bin” (Just the same, though I soon an exile am) reveals a bittersweet ambivalence between spirited selfassertion and cool rejection of the world. Here, the two consonant and mostly unison violin parts are countered by an edgy continuo, while the vocal soloist, clinging to a defiant motto, discovers in God’s upright friendship a redemptive antidote to the hostile world.

Whereas the aria reflects a hopeful “Immerhin” (Just the same), the ensuing recitative reveals a new tone, and not just harmonically. “Gott ist getreu” (God is e’er true) – a setting with such a motto is well able to radiate hope and steadfastness in a relaxed F-major key and then close with a rapturous arioso.

Bathed in the pastoral hue of three accompanying oboes, the following aria seems equally transformed, celebrating communion with God in intimate musical embraces and a lilting dance style. Now it is the world, so overpowering at the beginning of the cantata, that must survive alone and whose “falsche Zungen” (treacherous tongues) stand to be mocked. Here, the libretto and music radiate a joyful serenity that answers, and neatly dispenses with the tricky question of interest and pennies – hence of engaging with the world – with an encouraging smile. Indeed, those filled with the certainty of mercy cannot be corrupted by even the most euphonious music but, like Bach, will place it at the service of a well-understood gospel. Matters thus resolved, Adam Reusner’s powerful hymn “In dich hab ich gehoffet, Herr” (In thee I’ve placed my hope, O Lord) then strides purposefully through a setting based on a perfect fifth to prepare an inviting and nourishing space for the two “Brandenburg” horns to step in and join the hearty closing chorale.

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Rezitativ

Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht!

Hier muß ich unter Skorpionen

und unter falschen Schlangen wohnen.

Dein Angesicht,

das noch so freundlich ist,

sinnt auf ein heimliches Verderben:

Wenn Joab küßt,

so muß ein frommer Abner sterben.

Die Redlichkeit ist aus der Welt verbannt,

die Falschheit hat sie fortgetrieben,

nun ist die Heuchelei

an ihrer Stelle blieben.

Der beste Freund ist ungetreu,

o jämmerlicher Stand!

3. Arie

Immerhin, immerhin,

wenn ich gleich verstoßen bin,

immerhin, immerhin!

Ist die falsche Welt mein Feind,

o, so bleibt doch Gott mein Freund,

der es redlich mit mir meint.

4. Rezitativ

Gott ist getreu!

Er wird, er kann mich nicht verlassen;

will mich die Welt und ihre Raserei

in ihre Schlingen fassen,

so steht mir seine Hilfe bei.

Gott ist getreu!

Auf seine Freundschaft will ich bauen

und meine Seele, Geist und Sinn

und alles, was ich bin,

ihm anvertrauen.

Gott ist getreu!

5. Arie

Ich halt es mit dem lieben Gott,

die Welt mag nur alleine bleiben.

Gott mit mir, und ich mit Gott,

also kann ich selber Spott

mit den falschen Zungen treiben.

6. Choral

In dich hab ich gehoffet, Herr,

hilf, daß ich nicht zu Schanden werd noch ewiglich zu Spotte.

Das bitt ich dich,

erhalte mich

in deiner Treu, Herr Gotte.

Michael Guggenheimer

Standing by others.

Defending the freedom of the word

How the cantata “Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht” can also be read: as an appeal from Trogen for the protection of persecuted authors.

People take to the streets. They protest. They demand equality and justice. They are expressing their opinions in public. In Istanbul, thousands are demanding the right to demonstrate and are defending themselves against the destruction of a park. In Hong Kong, they are demanding a democratic election process. In Jerusalem, they protest against land confiscations. And whenever the state power refuses to enter into dialogue with them, protesters end up in prison, even if their slogans have anything but a criminal background. Their concerns, expressed publicly, are considered unlawful.

It is easy to become an innocent victim of a clash between protesters and state power. The Swiss writer Reto Hänny, for example, was remanded in custody in 1980. The reason: he was observing the Zurich riots. He stands on the edge of a demonstration, takes notes, collects documents, leaflets, projectiles and is arrested. Because he is carrying a leaflet, he is suspected of being an activist and is remanded in custody for a week. From prison he writes a letter to his colleagues in the Writers’ Union. It is a plea for freedom of expression. In his letter, which is on display in the exhibition room of the Swiss Literary Archives in Berne, he reminds them that it is the task of the writer “as a vigilant contemporary to be interested in social, i.e. human, problems, to observe as an eye-witness of an alert and critical mind, to deal with the problems, and this includes researching, collecting diverse documents, in order to contribute in his own way, in his own words, to a solution of the problems, to write along the thread of contemporary history in a literary work of art”.

Cases of arrests of local authors are rare. The Swiss writer of Kurdish origin Yusuf Yesilöz included a preface in a “History of Kurdish Literature” published by him in German, which talks about the difficulty of dialogue among Kurdish authors in four countries. The text had been written by a professor at the Sorbonne: “Because Kurdistan is divided between four countries, literature cannot circulate,” reads one sentence in her preface. When the Swiss citizen Yesilöz arrives at Istanbul airport, he ends up in jail because of this one sentence penned by a literary scholar, because the existence of a Kurdish people in the four countries, including Turkey, is not acceptable to the authorities in Ankara and so may not be expressed.

Authors live “among scorpions” in some countries

How precarious the situation of writers really is in many countries, how often authors live “among scorpions”, as the text of Bach’s cantata “Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht” says, is shown by a look at a document that is accessible to everyone on the internet. Every six months, the head office of the globally active organisation PEN International presents a document, its so-called “Caselist”, which lists all the cases of writers, translators, publishers and bloggers known to it who have not engaged in any criminal activity and yet are “expelled”, in prison or being prosecuted. The current edition of the Caselist counts 275 closely written sheets in A4 format! The information is constantly updated. A monthly bulletin also informs about the latest developments, for example about the Algerian author and filmmaker Abderrahmane Bouguermouh. He made a film in the language of the Berbers, a minority in his homeland, which is why he was sentenced to death by fundamentalists, narrowly escaped an assassination attempt and was able to flee Algeria to Europe. The language of the Berber minority is not recognised in his home country, although it exists.

Another example is Pinar Selek, author and founder of a feminist network in Turkey, who deals with the exclusion of minorities in Turkey. Her sociological study on the Kurdish question was a thorn in the side of some circles in her home country. In order to set limits to her possible influence, she was falsely accused of committing a bomb attack in 1998. She was sent to prison for two and a half years and was severely tortured. Released from pre-trial detention, she spent most of the trial, which lasted over twelve years, at large. Nevertheless, the prosecution demanded the maximum sentence of “life imprisonment with aggravated circumstances”.

A third case is the Saudi Arabian editor and blogger Raef Badawi. He was sentenced by a criminal court a few months ago to ten years imprisonment, 1000 lashes, a heavy fine, a ten-year travel ban and a ten-year media ban for “founding a liberal website”.

And finally, there is the case of the award-winning Egyptian actor Abol Naga: he dared to criticise Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in an interview for violating human rights, whereupon he was charged with “high treason and disturbing social peace”.

Threatened freedom of expression

Freedom of thought and expression, freedom of speech in literary works and in the media, and thus also the rejection of censorship, are under threat in many countries. At a time when once distant destinations have moved closer, countries where freedom of expression is being squeezed are no longer far from us. They are countries to which our weekend city breaks take us, where we spend our holidays, with whom we do business. Hungary, Turkey, Egypt, China, Mexico are among them, as well as Iran, Russia, Indonesia and Ethiopia. The caselist mentioned above counts over 700 cases. Prisoners or those persecuted by the judiciary who have been convicted of propagating violence or even using it, and those who have called for racial hatred, do not appear on this list.

Media workers, writers, and recently also bloggers, write about their country, write novels, stories, articles in which everyday life in their homeland is described; they often draw attention to injustices and grievances by writing. In legal proceedings against them, they are violated and deprived of their voice. Interrogations, court appointments, the permanent threat of ending up in prison, the compulsion to report to a police station every week, harassment by the authorities, such as the withdrawal of passports, the ban on leaving the country, as well as travel restrictions in their own country, all lead to the authors being prevented from working and continuing to write. Isn’t it said in the cantata “Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht” (Wrong world, I don’t trust you) that “honesty” – that of the observer, it should be added – is thus “banished from the world”. The aim of the falseness of those in power is to silence them, to drive them away. Standing by one’s own opinion requires courage. “Hypocrisy” on the part of the conformists comes to light again and again, “friends” become “unfaithful”, turn away from the courageous, “honesty” is thus “banished from the world”. In contrast to the cantata text, “friendship” cannot be built upon.

Raising the voice

It is important to raise one’s voice against the restriction of the free expression of opinion and against falsehood. Not only where this is prevented, but also from here, to show solidarity to the oppressed and threatened, to support them. We must not leave the oppressed alone. When those in power “grab them in their snares”, we should stand by them with our help. Especially we who have the privilege of living in a country where opinions can be freely expressed.

A look at the Caselist also reveals: according to their surveys, over 700 writers are currently being massively repressed in more than eighty different countries. 290 of them are serving long prison sentences, 170 others are under indictment for their publications, 45 were killed last year alone. It is well understood that none of these people have used violence or called for violence. These authors have done nothing but tell stories about their countries, about people and conditions in their homelands in novels, short stories, reportages and reports.

At the top of this sad hit parade is Turkey, with about 70 publicists in prison and 60 more involved in trials, some of them very lengthy. The second place is taken by the popular trading partner China – with the Nobel Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, incarcerated since 2008 for not more than seven sentences, and 39 other imprisoned writers. Eritrea and Vietnam follow. But such numbers do not tell the whole story, they do not portray the true lot of the persecuted.

In a country like Turkey, so many writers are imprisoned precisely because there is a vibrant intellectual scene and because there are many freedoms alongside state harassment. In this climate of legal uncertainty and discrimination – 70 per cent of arrested writers are Kurds – you can never be sure whether you will get a prize or a prison sentence for a text. This unpredictability has become rampant in many states in recent years.

Persecuted authors place their hope in solidarity in those countries where freedom of opinion – and above all freedom to express it – prevails. Help us, is their cry. Or in the language of Bach’s cantata “so stand me his help”, because: on your “friendship” we want to “build”. In order to help authors who are oppressed in their home countries, PEN International, in cooperation with other humanitarian organisations, tries to create places where they can live and create undisturbed by the authorities in their home countries.

As part of its work, PEN stands up for persecuted writers, journalists and publishers and their relatives. PEN tries to make contact with them and to inform the public both in the countries concerned and in our country about their fate. Together with other human rights organisations such as Amnesty International, PEN organises public campaigns or uses diplomatic channels to help writers who have been harassed, imprisoned, tortured and threatened with death and, if possible, to remove them from the grasp of their persecutors. Sometimes, rarely enough, with success. Two years ago, an international delegation negotiated with the then President Abdullah Gül about the situation of Turkish intellectuals and held a press conference in Istanbul to draw attention to the restrictions on freedom of speech. A passage from today’s cantata fits the outcome of these negotiations particularly well:

“Thy face,

which is still so friendly,

Is bent on secret destruction.”

With friendly expressions, Turkish ministers denied that freedom of expression was being hindered in their country. At that time, another PEN delegation in Mexico informed about the threat to journalists and writers who reported on the drug cartels and had to pay for it with their lives.

PEN helps persecuted authors to leave their homeland temporarily. A change of regime, an amnesty, a new law can make their return possible. Just when this work is successful, when persecuted writers are able to escape their tormentors and leave their homeland, a new problem arises very quickly: How can writers or journalists living in exile survive as writers whose language is not understood in the country of exile? For this reason, PEN has launched its Writers-in-Exile programme. The foreign writers who are accepted into this exile programme receive a stipend – initially limited to one year, renewable a maximum of two times – a flat, sometimes paid for by the host community. Counsellors and volunteers ensure that the exiles are helped with the many problems of everyday life. Consider this: these authors find themselves in exile in a country whose language they do not speak and whose culture and values sometimes require adjustments. At the same time, local authors try to establish contacts with publishers, translators and editors for the exiled, they organise readings and discussion events to introduce the authors, who are often completely unknown outside their home country, and their work to the public. In several countries, attempts are made to support exiled authors in such a way that they can stand on their own feet after a while or, if the political situation in their country of origin has improved, return to their home country. If they stay in Europe – with whatever residence status – for a few years or even permanently, it is particularly important for them to learn the language of their host country. Of course, it cannot and should not be a matter of demanding that those living in exile integrate completely in their host country and make themselves Swiss, German or Norwegian. Rather, it is a matter of creating conditions under which they can – to take up a word of Theodor Adorno – “be different without fear” and without discrimination.

Trogen as a place of appeal

It is precisely in working with people in exile that one can learn that the acceptance of cultural diversity and the idea of universally valid human rights are mutually dependent and not, as is sometimes claimed, mutually exclusive. Only if one learns to understand the foreign not as a threat but as an enrichment of one’s own culture can one understand that helping people who are in exile with us, and in many cases become friends, is also a great gain for us.

I tell about supporting oppressed people who are not allowed to express their opinions. I tell about it in Switzerland, a country that is proud to have given persecuted artists the opportunity to survive. Well-known theatre artists and writers found shelter here time and again. Many had to move on, however, because the boat was allegedly too full. Trogen, where every month a cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach offers an opportunity to reflect on the text on which the cantata is based, is the right place to talk about the fact that this country, unlike other European countries, does not yet offer homes to people who are persecuted for their opinions expressed in books, in newspapers and in the electronic media. Trogen, where once young people from abroad found shelter in the Pestalozzi Children’s Village, is the place where it can be demanded, in one of the most prosperous countries in Europe, to give courageous people who insist on respecting freedom of expression the opportunity to find shelter and space to write and reflect.

Soon, a sign will be set in Switzerland: a flat has been rented in Lucerne where, from next summer on, an exiled author will be able to write in freedom. This will be the first shelter in Switzerland. It is high time that this idea, which has long been established in 16 countries in Europe and North America, is put into practice in this rich country. They want to build on our friendship, the outcasts who stand by their word. It is time for this country to commit itself even more!

The Nobel Prize winner for literature, Herta Müller, once said: “For rescued persecutees, home is the place where one was born, lived for a long time and is no longer allowed to go. This homeland remains the most intimate enemy one has. You have left behind everyone you love. And they are still at your mercy, just as you were. We can hardly help over this pain, but we can listen to and help those who report it.”

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).