Widerstehe doch der Sünde

BWV 054 // For the Third Sunday in Lent (Oculi)

(Stand steadfast against transgression) for alto, strings and continuo

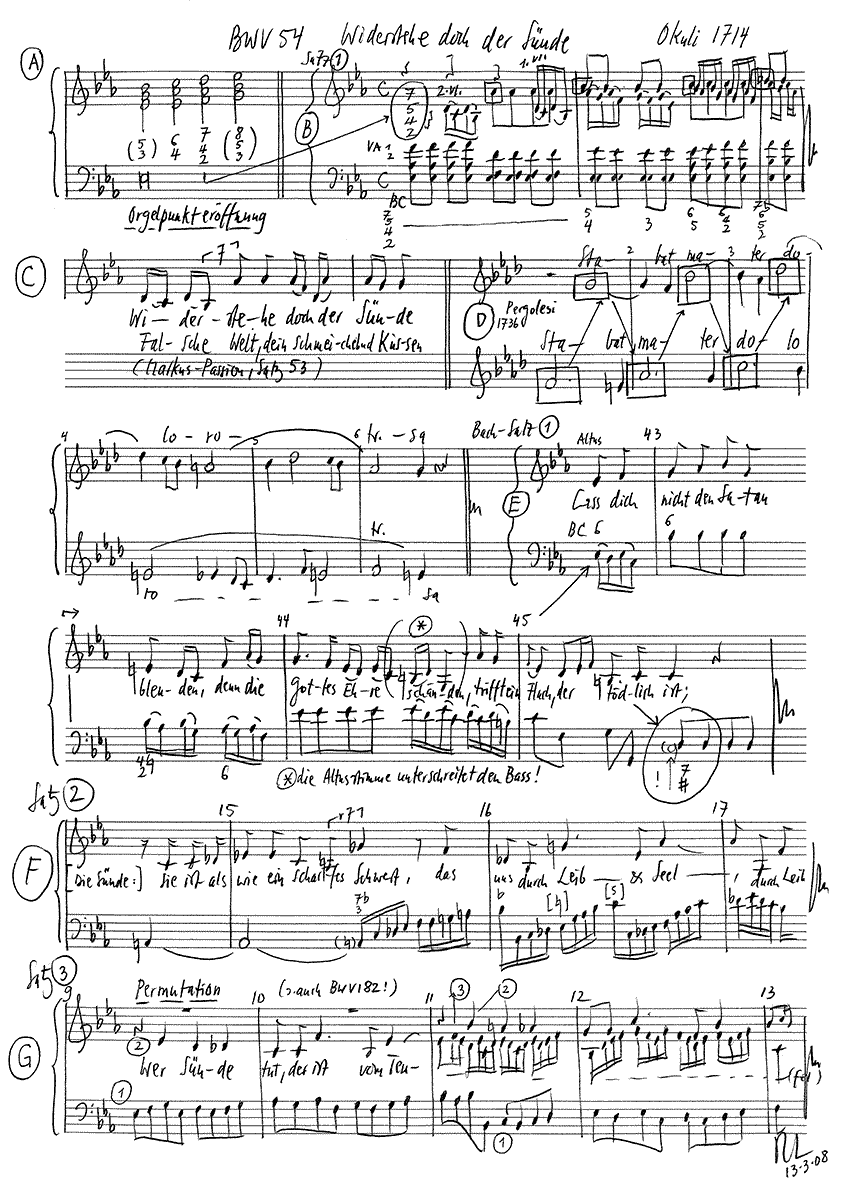

At first sight, the libretto and score suggest nothing spectacular. Comprising only two arias grouped around a recitative, BWV 54 reflects the simplest form of the new “sacred cantata instead of church music” (without bible texts and chorales) that was developed by theologist Erdmann Neumeister and his followers after 1700. Composed for solo alto, strings and continuo, the work cannot rely on great variety between the parts or contrasting tonal colours to engage the listener; moreover, the five-part string section with two violas is reminiscent of 17th century orchestration. All in all, one could easily be forgiven for expect-ing solid craftsmanship rather than a stroke of genius.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Soloists

Alto

Markus Forster

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Organ

Rudolf Lutz

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Thomas Sprecher

Recording & editing

Recording date

03/14/2008

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Composer of chorale No. 4

Rudolf Lutz

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–3

Georg Christian Lehms (1684–1717)

Text No. 4

Martin Jan (c. 1620–1682)

First performance

Probably on 14 March 1714

In-depth analysis

But: behold what Bach makes of this conventional structure! From the first notes of the opening aria, it is abundantly clear that nothing about this work is predictable, but that Bach is in his inventive element. The striking “wrong” chord with which the work commences jars the ear, and this dissonance underlies the movement much in the way that original sin insidiously pervades all life.

Theologist and Bach scholar Friedrich Smend postulates that Bach reused this unique music for the aria “Untrue world, thy fawning kisses” of the St Mark Passion per-formed in 1731 and revised in 1744 (of which only the libretto survives) – certainly no far-fetched assumption. An unrelenting dissonance pervades the entire aria, with the penetrating bow strokes of the violas and basses and incessant friction of the violins barely giving the vocalist a moment to breathe. In this movement, Bach is not concerned with the luring temptation of sin as described in many baroque works; rather, he confronts his listeners with the overwhelming undercurrent of evil against which humans must struggle with all their might. For Luther and Bach, the devil was not simply a metaphor, but an all too real adversary and dogged companion. Aria no. 3 does not mince words: “Who sin commits” has not simply erred in his ways but “is of the devil”, of whose poison one can so easily be tainted. The theme of this aria, a chromatically descending passage that illustrates the descent into wickedness and sin, is fittingly accompanied by whirling gestures that conjure up a danse macabre. To lend the sound more clarity at this point, the violas and violins unify into one voice. (In a lighter version, this theme also reoccurs in the trio sonata in C

major BWV 1037, a work that was long attributed to Bach, but later identified by Bach expert Alfred Dürr as a masterpiece of Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, one of Bach’s students.) Between the two arias, Bach situated an articulate recitative which starkly illustrates the “empty” and deceptive character of sin and which ends with the “sharpened sword” from Luke 2.35 piercing “soul and body”.

Neither the exact period of composition nor the placement of the cantata in the church year can be determined with certainty. The low register of the vocal part suggests that it was probably composed for the higher choir pitch of the Weimar Castle chapel; further-more, the old-fashioned instrumentation and surviving transcription from the Weimar organists Johann Gottfried Walther and Johann Tobias Krebs is also indicative of Bach’s ten-ure there.

The exact purpose of the cantata is equally obscure. Although the librettist Georg Christian Lehms designated his poem as a meditation on Oculi Sunday, Alfred Dürr argues that it was written for the Seventh Sunday after Trinity on the basis of the work’s probable chronology. It also cannot be excluded that Bach may have intended the cantata to be a composition “in ogni tempo”, in other words, without a fixed place in the church year. It is known that text excerpts of cantatas similar to the libretto of BWV 54 have been documented for the years 1739 and 1748 in the Saxon city of Leisnig. Whether or not they were actually intended to be repeat performances of BWV 54, they are recorded in Leisnig as having been assigned to the first and twentieth Sundays after Trinity, respectively. When attempting to place the work, it is also worth mentioning that Michael Maul has observed a striking similarity between the spectacular dissonance that opens the first movement of the cantata and Telemann’s opera aria “Harte Fesseln, strenge Ketten” of 1711.

In our recording, the cantata closes with a newly composed chorale movement to a verse by Martin Jan (1620–1682). True to the baroque practice of adapting manuscripts and presenting them in a new form, an expert cantor from St Gallen has developed the revered original a little further and imbued it with the spirit of the times…

Libretto

1. Arie (Alt)

Widerstehe doch der Sünde,

sonst ergreifet dich ihr Gift.

Lass dich nicht den Satan blenden;

denn die Gottes Ehre schänden,

trifft ein Fluch, der tödlich ist.

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

Die Art verruchter Sünden

ist zwar von aussen wunderschön;

allein man muss hernach

mit Kummer und Verdruss

viel Ungemach empfinden.

Von aussen ist sie Gold;

doch will man weiter gehn,

so zeigt sich nur ein leerer Schatten

und übertünchtes Grab.

Sie ist den Sodomsäpfeln gleich,

und die sich mit derselben gatten,

gelangen nicht in Gottes Reich.

Sie ist als wie ein scharfes Schwert,

das uns durch Leib und Seele fährt.

3. Arie (Alt)

Wer Sünde tut, der ist vom Teufel,

denn dieser hat sie aufgebracht.

Doch wenn man ihren schnöden Banden

mit rechter Andacht widerstanden,

hat sie sich gleich davongemacht.

4. Choral (zugefügt; nicht im Libretto und der Kantate)

Jesum nur will ich liebhaben,

denn er übertrifft das Gold,

und all andre teuren Gaben,

so kann mir der Sünden Sold

an der Seele gar nicht schaden,

weil sie von der Sünd entladen,

wenn er gleich den Leib ersticht,

lass ich meinen Jesum nicht.

Thomas Sprecher

“Sin or Virtue?”

Tracing the changing meaning of the reprehensible.

I have always liked the word sin, both in its colloquial and its colloquial theological sense. Sometimes I can imagine something with it, sometimes I can associate something very concrete with it, which is helped by the fact that sin is female. According to Christian tradition, it was a woman who was the first to commit sin. Then again, sin becomes something completely abstract to me, loses all its linguistic, religious and cultural-historical connotations and remains as a pure beautiful sound, like a shell whose shape one traces when speaking, in whose depths the evil holds, like reasons or gullets.

The cantata poem “Widerstehe doch der Sünde“, probably written around 1711, is almost 300 years old. It is not one of the immortal treasures of German literature, and it would have succumbed to its mortality long ago if it had not been carried into eternity by music. Bach’s cantata art is not dependent on masterly texts. A cantata is singing; and the meaning of singing ultimately lies in the singing, not in what is sung.

The author, the Darmstadt court poet Georg Christian Lehms, has turned his work into a didactic poem. After vividly explaining what happens if one does not resist sin, the conclusion communicates the consequences if one is able to do so. Formally, it is structured like a legal sentence. An if-then formula is attached to a fact. It could be written like this in the penal code: Whoever falls into sin is punished with its poison. The reward also corresponds to the penal code: whoever resists sin remains free from punishment. Positive incentives are missing there as well as there. Nor can anyone who commits a crime derive anything from the fact that he did not do so on another occasion. Otherwise, every manslaughterer would bring those still alive into the fray to exonerate him.

When I first dealt with this cantata text, I was in the USA, which gave me the opportunity to watch various televangelists in the same hotel rooms. The type of preacher has always fascinated me. The cashing-in professional scrounger, the salesman, lawyer and politician, the showman and actor, the enlightenment-resistant mixture of professionalism, rhetorical boorishness, shamelessness and mass appeal, the theologically dressed-up demagogy. These preachers are a reflection of that priest Nietzsche, who does not live badly from sins.

Our narrator is also a preacher, and one who still maintains the claim to the administration of sins. The Enlightenment has raised some questions about this claim that cast suspicion on the speaker. How does he know so exactly what sin is all about?

But at the beginning of the 18th century, the Christian vocabulary could be used as a matter of course. Everyone knew what sins were. “Beautiful”, it was said, they were, but lies only and deceit, as false as the night. They glitter like gold, but in reality they are an “empty shadow”, a “grave”. By warning against “marrying” sin, the poem places it in a libidinous field. But it does not go further into its content. It does not offer a casuistry of sin, but rather deals with “sin” in a very common way. Sin is sin, all sins lead to one sin. No distinction is made between venial and mortal sins. In the realm of the forbidden, all sins are equal. The verb “to sin” also indicates that to sin is to do and not merely to let happen. And indeed, at the end it says in all clarity: “Whoever commits sin is of the devil”. Sin lies in sinning.

The diabolical act is followed by the sanction. Whoever falls into sin is punished. Here the poem becomes more explicit. The sinner pays in half a dozen, namely 1. with being poisoned, 2. with a deadly curse, 3. with sorrow, vexation and trouble, 4. he is denied God’s kingdom, 5. he is pierced with the sword, and 6. finally he falls into the stigma of being of the devil. The poet comes up with a great deal of punishment, supported by the Bible, over the sequence aria – recitative – aria. This enumeration is not an increase to the ever more ghastly, and one should not take it quite literally, but it always has an ominous pregnant effect. What they have in common is the negative aspect of punishment. Perhaps the most important message is that sinners do not go to heaven. In Old Testament terms, God spits them out.

To avoid punishment, one must resist sin. There are no other options according to this scheme. One cannot inoculate and immunise oneself against sin. You cannot avoid it because it stalks you. You cannot get rid of temptation. The most pious cannot live in peace if this does not please the evil devil. So there is no way without unceasing resistance. It consists in not doing sin. One must ward it off by resolute passivity, and that, according to the poem, with the means of “right devotion”.

To our ears, the word “resistance” has a political-military sound. In the cantata text, too, it is a warlike term, for the strongest possible resistance is needed against the seductive power of sin. Now, however, the first line of the poem has a “doch” inserted: “Resist sin”. This is an appeal, but not a harsh one. It is not “Resist sin!” but “Resist sin”, and the filler word “yet” almost softens the command to a plea. For metrical reasons it was not used, because one could easily have said “Resist sin always” or “Resist sin well” without endangering the delicate order of the syllables. The “nevertheless” undermines the whole militancy, whereby it must remain open whether the dangerousness of sin is not so far off after all or the appeal to resistance is one of profound hopelessness. In any case, the victory is never final. The fact that sin has departed does not mean salvation. It will come back again, very soon, he who lives knows that. Perhaps it will present itself with an even more beautiful appearance and then entice and tickle us so much that it is unbearable.

If a teacher, a father, a preacher wants his listeners to avoid something, he must not leave it at the lash. Here, too, more beckons. He who resists sin will be rewarded. But what is the reward for steadfastness? Well, the reward is somewhat pale, namely pure negation. Sin “departs in a moment”, no poison seizes me, no sharp sword passes through me, no deadly curse strikes me, I feel no sorrow or vexation, and my chances of entering God’s kingdom are as great and as small as before. I do not experience the pleasure of sin, but everything else remains the same. There is, at least according to this work, no account of averted sins whose status would be raised and bindingly noted in higher places.

Just as Bach’s music shapes time and space, so does this little poem. There is a before and after, a deceptive outside and a true inside, an above and a below. In general, opposites are used, light and dark, the earthly contrasted with eternal life, the grave with heaven, Satan with God.

Satan and God. There is also certainty about the extraterrestrial personnel around 1711. God knows every child. In our poem, however, he remains in the background, just as, between us, the devil is generally far more theatrically appropriate than the Christian God, who only with difficulty rises to become a colourful figure on the stage. There is no direct mention of him, only of his honour. Whoever sins, it is said, desecrates it. That God has an honour is perhaps quite humanly conceived and felt, just as human ideas in general would always come too close to the divine and harm it if they reached it.

However, God is not only the victim, but also the punishing authority, which seems somewhat outdated from the perspective of the rule of law. From God comes the deadly curse on every sinner, he wields the sharp sword and denies his kingdom. But what does the devil do? He tempts, lures and beguiles. He is after poor souls as some men are after skirts. He must not be easy, nor does he have the privilege of resting from a creation. Rather, he must be active, that is, he must catch souls. That is what man, who according to the Bible is god-like and not devil-like, has in common with him. He too has to work, in this case he has to resist. Thus man and the devil move on the same field of effort, while God can keep out and quietistically restrain himself, insofar as he does not have to rule in the high task of his honour as executor of punishment.

Even to understand a cantata from its historical existence requires a church-musical sensorium. And linguistic works age even faster than musical works. Time carries us on. We are placed in a world that is far removed from that of Bach and Lehms. Distance and difference have inscribed themselves in the identity of what has become foreign. It is difficult to hear and read the way one heard and read 300 years ago – presumably. This historicisation is only possible to an approximation, and it requires a significant translation, a resetting.

But of course one can also read with today’s eyes. Such texts pose many questions for an enlightened mind, let’s say one that is in the never-ending process of enlightenment. Who, for example, determines what sin is, who has this power of definition, and why does he do it? And how would sin be defined? Reduced to the profane, sin is often understood as an action or omission that is considered wrong for God knows what reason, without any theological explanation being associated with it. One speaks of sins in the case of violations of dietary regulations or sexual norms. Such missteps also cost and are punished, and whether heaven is the avenging power or the judge, the teacher, the bad conscience, the laws of physics, the market, the body, the tax administration, is irrelevant in terms of effect.

The cantata text mentions the apples of sodom. They are seen as a symbol of hypocrisy because, according to tradition, they resemble edible fruit on the outside but dissolve into smoke and ashes when you pick them. But the apples of Sodom are also reminiscent of the apple that Adam is said to have eaten. His fatal act was to bite into the forbidden fruit. If Adam had been an Asian, the Christians would still be sitting in paradise, because this Asian Adam would not have eaten the apple, but the snake. The joke should not be misunderstood as a slide into the cheap, but rather approved as a symbol for the changeability of sin in terms of content.

Could it be that every culture, every time, even every human being has its own sins? That my system of sin coordinates is not that of my children? Compared to 1711, people’s possibilities for action have expanded enormously, and with them the seriousness of their sins, the dubiousness of their actions. Smoking, flying, heating, begetting children, everything can be fraught with serious disadvantages and become morally highly questionable. In Lehms’ poem, fronts of a simplicity and purity still prevail that can never be achieved in today’s Western-style world of life. Not everything that glistens is sin, and not every temptation shows itself through glitter. In the last hundreds of years, the devil has greatly increased his refinement. In practice, it is not always clear what is sin and what is resistance. In the world of ambivalences, sin may also lie in resistance and this may become sin, and the goal of freedom from sin can be missed in all ways.

Nor do cunning and enticement always proceed entirely from the other. In many stories of seduction, it is not entirely clear who pulled and who sank. The structure of seduction can be extremely complex, not entirely obvious to the personae dramatis themselves, and just as being seduced is not always an unintentional, loose-willed affair, seducing is not always an act of intention and plan. And finally, punishment in life is not always as clear-cut as in the Old Testament or the Penal Code, nor is it of the same severity for everyone. Some, for example, did not consider it bad to be seized by blond poison. Then the punishments would also have to be redefined according to the contemporary calculation of sins. For if the punishment is less than the pleasure in sinning, then it is worth it in the end, and that would not be in the spirit of the inventor.

Finally, resistance must also be redefined. Passive refusal is not enough. Forms of defence, as every officer candidate learns, also include counterattack. One strategic option would be to try to beat the devil with his own weapons and seduce him himself. However, the authority that could determine sin and sanction for the devil is unclear. What deed would he have to be tempted to do in order to be found sinful and guilty? And what would be his punishment? The human imagination, or let us say: pubescent residues that happily preserve a gran of creative childishness for the adults, may after all think up a few heavenly torments here, devil-like chastisements at the hands of the upper rulers.

Today, the model of sin and punishment seems too crude, too mechanical and too static, and does as little justice to the dynamics of human ethics as it does to the nature of our spirit, which we do have in order to rise above our conditions. If you want to get ahead, you have to break the rules, that is the law not only of political or aesthetic revolutions, and under this law, breaking the rules is not a sin but a commandment, namely resistance to the vice of stagnation. In world history, it works unfavourably well to invoke it. Every dictator has claimed that history will absolve him, and in fact posterity has almost always found an absolution.

So our task today would not be to resist sin, but to recognise and name it in the first place. One does not sin out of disobedience, not out of a lack of resistance alone, but already out of a lack of power to recognise or a lack of courage to recognise sin. The recognition of real and true sin cannot be done and settled once and for all, but must unfortunately always be accomplished anew. For just as every action can become a crime, are the circumstances thereafter, every action can also become a sin. What was right or harmless yesterday may belong to be forbidden today.

And there are still other circumstances that limit the practical meaning of sin in life. It can only exist where there is decision, where resistance would be possible. Above all, however, only part of the work of life is done with it, for where it is to go in non-sinning still remains completely open. Sin says what I should not do; but what I should do must first be determined in the open horizon of human existence. Here the sin-avoidance strategy does not help.

Of course, sin has also led to the establishment of a scientific discipline. The doctrine of sin is called hamartiology. In the classical theological edifice of thought, hamartiology is a part of anthropology, which is a part of the doctrine of creation, which in turn is a part of dogmatics, and dogmatics is, you guessed it, a part of theology.

Many years ago, as a court clerk, I represented the District Court of Zurich in a working group that dealt with sexual offences and also the Zurich hustling plan on a regular basis. The working group also included two officers of the Zurich vice squad, whose main duties included checking confiscated film works day after day in darkened rooms for sodomistic and other criminal content. An indispensable occupation in terms of criminal law, but absurd in terms of everyday philosophy and psychologically gruesome. I was reminded of it when imagining how hamartiologists indulge in their favourite object day after day. They collect the sins, dissect them like high school students dissecting stick insects and fabricate highly dogmatic chiselings from their findings, from which one can then deduce how many rolls of barbed wire and other roadblocks the good Lord is using to block the way to his heaven.

But the hamartiologists are not the only ones who bend over sin with a sharp eye. In the free market economy, sin, like everything else, has become a commodity that is taken care of by various new or even newly named professions: the sin registrar, the sin inventor, the sin designer, the sin counsellor, the sin seller, the sin builder, the sin priest, the sin improver. One only seemingly enters the realm of the silly with such remarks. For in a world of post-post-postmodern arbitrariness, where nothing is sacred any more, nothing is sinful any more. Incidentally, it seems that the devil has had to surrender some of his power of seduction to the world of commodities and its marketing artists. Advertising also promises more than what is advertised delivers. That is its nature. Without this euphemistic difference, we would buy much less and marry much less.

The devil himself has also moved with the times and evolved since 1711. He lost his ugly charisma. In “Faust” he became worldly. Goethe’s metamorphosis transformed him into an intellectual. In “Faust”, however, the concept of sin was also broken up. Mephistopheles distinguishes between the “cheerful sins” of the Greeks and the “gloomy” ones of the Christians. Nietzsche took up this polarity when he reflected on the “origin of sin” in “Merry Science”. Sin was “a Jewish feeling and a Jewish invention”. In this respect, Christianity had “Jewishised the whole world”. This can be felt in the degree of strangeness that “Greek antiquity – a world without feelings of sin – still has for our sensibilities”. The feeling of sin is “a laugh and a nuisance” to a Greek, a feeling of slaves.

Nietzsche also criticises the concept of sin: it presupposes a God who, although overpowering, is nevertheless vengeful. Every sin is an insult to majesty, and the act of human degradation has only the purpose of restoring divine honour. What particularly strikes Nietzsche, however, is that God leaves “this honour-seeking Oriental in heaven” unconcerned “whether harm is otherwise done with sin”. One can at least credit today’s colloquially trivialised concept of sin with having taken up Nietzsche’s criticism. Sin is not only an offence against God, but also or even only against human beings. God could not maintain his monopoly on the sacrificial role.

Besides Nietzsche, since the Middle Ages many spirits and serious doubters have not so much opposed the Christian dogma of sin as tried to counteract the bad reputation of sin, but in doing so, of course, they also undermined the dogma. “Those who dare not sin”, Erasmus of Rotterdam said, commit “the greatest sin”. Dante thought that the more interesting discussions were about those who go to hell. Some pointed ironically to the highly personal nature of sin. Those who are called to celibacy sin when they marry. Those who are called to drink, however, do so when they remain sober. For one of Frank Wedekind’s stage heroes, sin was merely “a mythological term for bad business”. The Italian writer oriana Fallaci noted that when Eve plucked the apple, it was not sin that was born, but a great virtue, namely disobedience. And the praise of sin has become proverbial in the saying that in old age one regrets above all those sins that one did not commit in youth.

For a long time, God has been recommended to seriously address the question of whether he exists. Johann Sebastian Bach would not have understood such hubris. His music is music from God’s point of view. Like all culture, it is man’s answer to his non-divinity. For man has a hard time. God has been holding back since creation and some later interventions and sendings, and whether that question really weighs on him, we do not know. According to the Christian reading, the devil, too, has an unchanged, clear set of duties, despite all the refinements. But the ontologically indeterminate and unhoused human being must again and again painfully give himself a framework and direction in a self-creation that is intricately close to self-abnegation. Nowhere, however, does he succeed better in redeeming himself, his finite, mammalian corporeality, than in music, with sounds and tones, these luminous messengers to the so worldly weighted provinces of the soul. Thanks be to Bach.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).