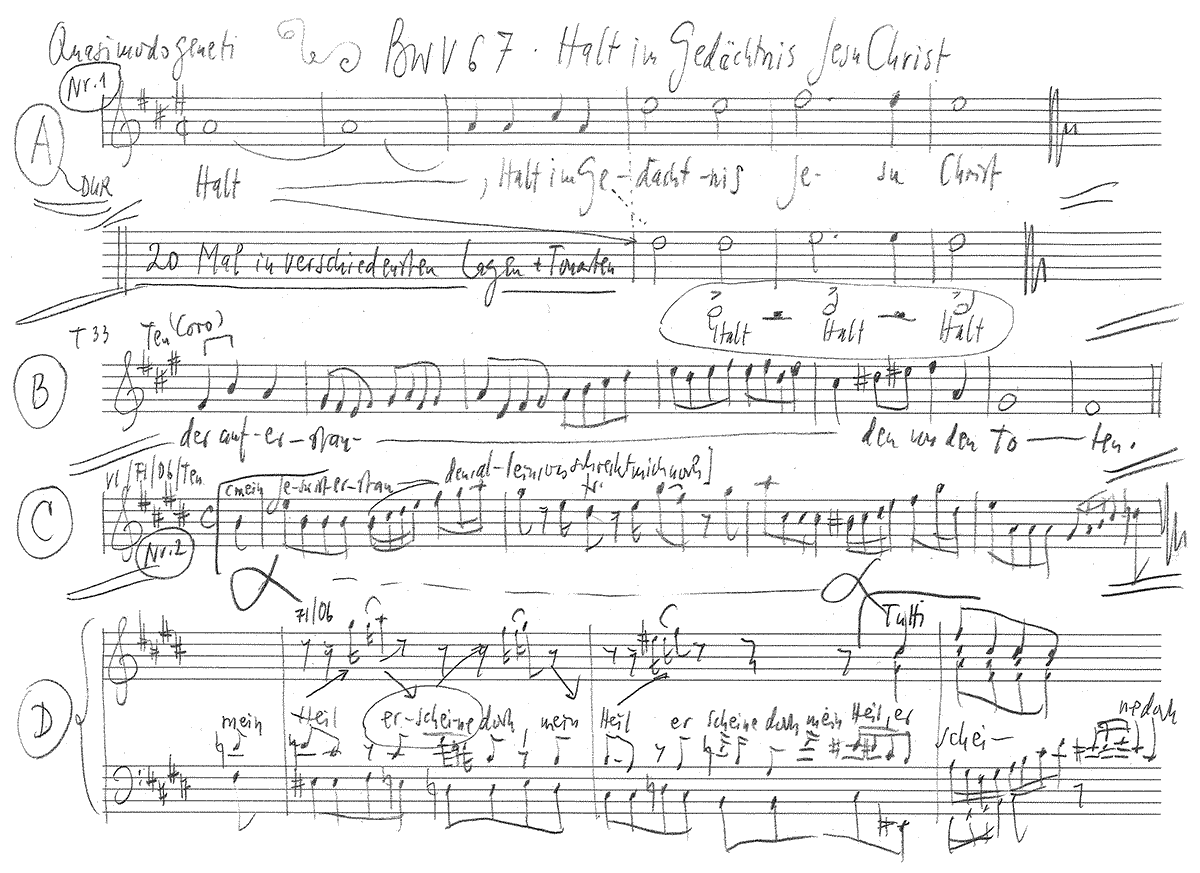

Halt im Gedächtnis Jesum Christ

BWV 067 // For Quasimodogeniti

(Hold in remembrance Jesus Christ) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, corno da tirarsi, transverse flute, oboe d’ amore I+II, bassoon, strings and basso continuo

The introductory chorus to cantata BWV 67 opens with a heroic horn figure and a triadic, fanfare-like theme that underscores the proximity of Quasimodogeniti Sunday to the Easter events of the preceding week.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Jennifer Rudin, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Alexandra Rawohl, Damaris Rickhaus, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Valentin Parli, Oliver Rudin, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Elisabeth Kohler, Mechthild Karkow, Martin Korrodi, Fanny Tschanz

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Zimmermann, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Kerstin Kramp, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Transverse flute

Claire Genewein

Corno da tirarsi

Olivier Picon

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Manfred Koch

Recording & editing

Recording date

04/25/2014

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Second letter to Timothy 2:8

Text No. 4

Nikolaus Herman (1560)

Text No. 7

Jakob Ebert (1601)

Text No. 2, 3, 5, 6

Poet unknown

First performance

Quasimodogeniti,

16 April 1724

In-depth analysis

The introductory chorus to cantata BWV 67 opens with a heroic horn figure and a triadic, fanfare-like theme that underscores the proximity of Quasimodogeniti Sunday to the Easter events of the preceding week. In this movement, the disciples’ painful dichotomy of feelings – elation at the resurrection and devastation at the memory of the events preceding it – is impressively captured in the contrast between the gestural call of “hold” and the fugal, ascending triadic theme “in memory Jesus Christ who is arisen” that completes the phrase. The buoyant setting alternates choral concerto and fugal elements that ultimately merge to conclude the setting with a powerful choral dictum that reiterates the admonitory message of the text.

The following aria is set for tenor voice, a register holding the promise of victory. With its assertive gestures and brevity of form, the movement is reminiscent of Bach’s secular, occasional cantatas from his Cöthen years: the music’s speech-like instrumental motives and unpretentious decorative figures refrain from all theological-poetic fancy.

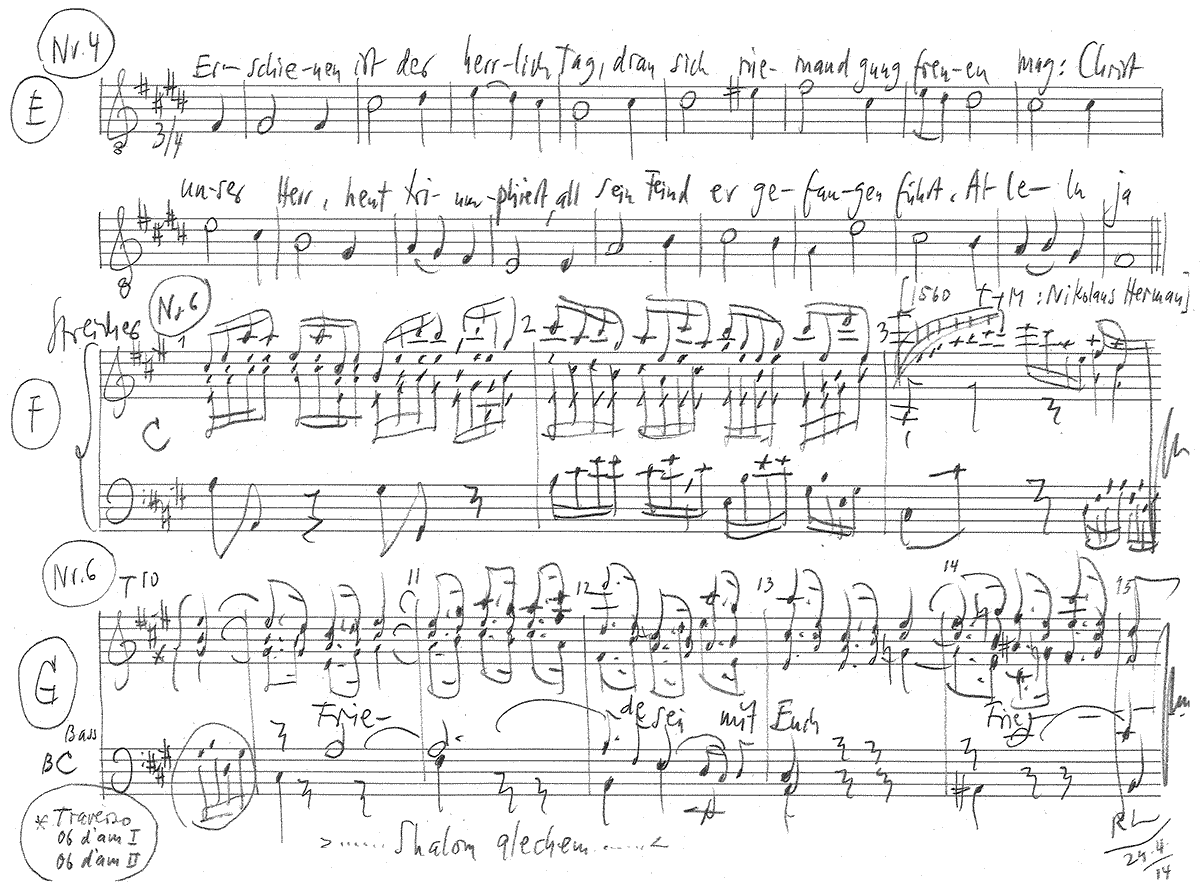

This is followed by a dramatic alto recitative that evokes the resurrection in powerful images of overcoming hell before announcing the common “song of praise… set upon our tongues”, a setting that lends powerful resonance to the attacca hymn verse “Appeared is now the glorious day”. By inserting these communal interludes in the cantata form, Bach presents the early Easter chorale as a common denominator that unites the performers and congregation; such moments reinforce how even Bach’s most elaborate compositions remain practical church music that have a direct connection to the liturgy.

After this unanimous pledge to the Easter message, the continued alto recitative presents a veritable “Confutatio” that acts as an internal test of externally promised faith: the enemy is powerful, and only active hope in the promise of the Lord remains amid earthly turmoil. This fighting spirit is then sustained in the ensuing aria, which numbers among Bach’s most interesting settings from his Leipzig era, and not merely on account of its form: here, the bass soloist interrupts the hectic broken chords of the string orchestra and, accompanied by the ethereal timbre of the woodwinds, transports the events of Emmaus into the present moment by proffering the sign of peace in an emphatically decelerated triple metre. The agitation of the disciples – torn between high morale, trepidation and gratitude – continually erupts in rapid bursts, yet each time Jesus intervenes to pacify his flock. By keeping the bass und upper vocal parts separate, Bach effectively presents the world of humankind and Christ as fundament as distinct spheres that, despite their separateness, can enter into an intimate dialogue in which the Saviour, with his tender gesture of peace, has the last word.

The hymn verse “Thou prince of peace, Lord Jesus Christ” then provides for a conclusion of laconic precision and simple persuasion: from the exultant rejoicing of Easter, quiet joy and humble hope have arisen.

Libretto

1. Chor

»Halt im Gedächtnis Jesum Christ,

der auferstanden ist von den Toten.«

2. Arie (Tenor)

Mein Jesus ist erstanden,

allein, was schreckt mich noch?

Mein Glaube kennt des Heilands Sieg,

doch fühlt mein Herze Streit und Krieg,

mein Heil, erscheine doch!

3. Rezitativ (Alt)

Mein Jesu, heißest du des Todes Gift

und eine Pestilenz der Hölle,

ach, daß mich noch Gefahr und Schrecken trifft?

Du legtest selbst auf unsre Zungen

ein Loblied, welches wir gesungen:

4. Choral

Erschienen ist der herrlich Tag,

dran sich niemand gnug freuen mag:

Christ, unser Herr, heut triumphiert,

all sein Feind er gefangen führt.

Alleluja!

5. Rezitativ (Alt)

Doch scheinet fast,

daß mich der Feinde Rest,

den ich zu groß und allzu schrecklich finde,

nicht ruhig bleiben läßt.

Doch, wenn du mir den Sieg erworben hast,

so streite selbst mit mir,

mit deinem Kinde:

Ja, ja, wir spüren schon im Glauben,

daß du, o Friedefürst,

dein Wort und Werk an uns erfüllen wirst.

6. Arie (Bass) und Chor (Sopran, Alt, Tenor)

Bass

»Friede sei mit euch!«

Sopran, Alt, Tenor

Wohl uns!

Wohl uns, Jesus hilft uns kämpfen

und die Wut der Feinde dämpfen,

Hölle, Satan, weich!

Bass

»Friede sei mit euch!«

Sopran, Alt, Tenor

Jesus holet uns zum Frieden

und erquicket in uns Müden

Geist und Leib zugleich.

Bass

»Friede sei mit euch!«

Sopran, Alt, Tenor

O Herr!

O Herr, hilf und laß gelingen,

durch den Tod hindurch zu dringen in dein Ehrenreich!

Bass

»Friede sei mit euch!«

7. Choral

Du Friedefürst, Herr Jesu Christ,

wahr’ Mensch und wahrer Gott,

ein starker Nothelfer du bist

im Leben und im Tod:

drum wir allein

im Namen dein

zu deinem Vater schreien.

Manfred Koch

“The Memory of the Divine”

Christians remember the deeds of the Son of God and his suffering on the cross. This is not simply recounting the past, but making God’s presence perceptible. The cantata BWV 67 “Halt im Gedächtnis Jesum Christ” begins musically with a wake-up call: “Halt! – don’t go on, but reflect on the essential, remember Christ”! And this rethinking draws us into a real drama of the soul. Adam and Eve, it is said, lived timelessly in paradise, completely given over to the moment at hand, without concern for the future and without thoughts of their past lives. “Memory,” wrote the Italian painter and philosopher Alberto Saviano in 1921, “was born at the moment when the displaced Adam crossed the threshold of the earthly paradise.” With the Fall, therefore, we fell into time, we are in a sense split beings, never fully absorbed in our present, but always also living out of what we have been in our past and want to be in our future.

As plausible as this philosophical interpretation of the paradise story is, it is openly false. Although one can hardly imagine Adam and Eve as authors of autobiographies, they were not memoryless. How else could God have warned Adam not to eat from the tree of knowledge? And Eve, in conversation with the serpent, remembers this statement, quoting the Lord: “of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God hath said, Eat not of it, neither touch it, lest ye die.” (Gen 3:3) At the beginning of human history according to the Old Testament, there is a commandment that must be remembered. Failure to remember or wilful ignoring of what is recorded in it entangles one in guilt.

The urgent admonition not to tamper with the tree of knowledge is the first sentence in the Old Testament that God ever speaks to man. “Hold in remembrance” therefore already appears here, at the very beginning. It can be said without exaggeration that it is the fundamental sentence of the entire Bible. Judaism and Christianity are the two religions of remembrance par excellence; in both – as nowhere else – remembrance is a religious duty. The best way to understand why this is so is to consider the historical conditions under which they came into being. Judaism required its followers to believe in an invisible God who could not initially be worshipped in magnificent cults at fixed holy sites. The covenant between Yahweh and the people of Israel – that was the covenant between an otherworldly God, who had no temple on earth, and a people on the move. In the hardships and temptations to which the people are exposed in the no man’s land between the cultures of Egypt and Canaan, God repeatedly brings himself to mind as the one “who brought you (Israel, M. K.) out of Egypt”. The promise of salvation is based on this memory. However, it is in danger of being forgotten in an environment where there is nothing to bear witness to it. Hence the call, constantly repeated in the Old Testament, to remember Yahweh’s original act of deliverance, not to forget this intangible God, so that he in turn does not forget his people. Later, in the Babylonian exile – that is, after the conquest of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. by Nebuchadnezzar – remembering one’s own God in the midst of a hostile environment was the most important means of survival. This basic constellation – remembering God in a culturally different, mostly hostile environment – remained binding for the further history of Judaism. I probably do not need to elaborate further on how terribly the cultures that absorbed Jews often reacted to their faithfulness to memory.

Christianity, too, was extremely dependent in its beginnings on the preservation of a memory for which there was no external evidence in the Roman Hellenistic culture of the first two centuries. Christians commemorate the deeds and sufferings of the Son of God – centrally, of course, his sacrifice on the cross – but not in a way that recounts past events, but in such a way that in this narrative memory God becomes present, his presence perceptible. That is why the central ritual of Christianity is a meal of remembrance, which Jesus himself once instituted – “do these things in remembrance of me” – but in which the remembered is at the same time to become present in an overwhelming way. I am not a theologian and will be careful not to contribute anything substantial to the endlessly discussed question of how real the presence of Christ in the Eucharistic celebration is to be understood, i.e. whether bread and wine are ‘only’ signs of remembrance or whether the Saviour is bodily present to the faithful in them. But one can well imagine – regardless of theological subtleties – how tremendously important it was for the first Christians to remember Jesus in such a way that this act was a most intense visualisation, an experience of his divine power, which could strengthen the own soul, the will to self-assertion, of the religious outsiders. The historically earliest Communion passage in the New Testament is found in the Apostle Paul’s 1st Letter to the Corinthians (a text from about 54 AD). It is an exhortation to the followers of the new doctrine there to celebrate this meal consistently and in the right spirit, apparently under the impression of signs of disintegration that threatened the continued existence of the church in the pagan environment. “Keeping Jesus in mind” – that was precisely what gave support. This experience was and is important. Those who remember him feel, when such remembering takes hold of them completely – in spirit, soul and body – that Jesus also remembers them. The celebration of the Lord’s Supper is suitable to calm the age-old human fear of being forgotten; it is, like every prayer, an appeal to God to accept man, despite his inconspicuousness and sinfulness, into his mighty, protective memory (“What is man that you remember him?”, Psalm 8).

But how does the believing Christian arrive at such intense remembrance, filled with divine presence? With the rise of Christianity as a state religion, the Christian Church became an institutional power that claimed to have the appropriate means to bring about such an experience of God. The goal of the medieval mass was to make God/Christ sensually tangible in every conceivable way: through the colours and golden glow of windows, pictures and mass vestments, through light displays and scents that filled the church space, through exquisite cultic sign language, through the touching and kissing of relics, and so on. Martin Luther famously criticised all this as external pomp, indeed as diabolical stimulants of the depraved worship of his day, a spectacle of the senses that distracted from the essential – listening to the biblical word. But of course, Protestant worship does not dispense with sensual means of exaltation; indeed, it develops a much more inward and therefore perhaps even more spiritually effective means of exaltation to its highest perfection: music. It is precisely through Bach that church music has become an unparalleled emotional powerhouse. It is no coincidence that artists of Jewish origin such as the siblings Fanny and Felix Mendelssohn only seemingly said in jest that they had not actually converted to Christianity but to Johann Sebastian Bach.

Our cantata should also be seen against this background of a Protestant emotionalisation of memory. It is much more than a setting of the Christian fundamental sentence, an addition to its already catchy meaning. When the word becomes music, it unfolds an affective power that transcends language. The introduction is already characteristic, with the “Halt” repeated three times in succession, before it is clear what is to be held here, indeed that it is a matter of holding on at all. The cantata begins musically with a pause that is at the same time a wake-up call: ‘Stop – don’t go on like this in everyday life, but reflect on what is essential, remember Christ’. And this rethinking, by virtue of the musical interpretation, is not a mere change of subject. Instead, we are drawn into a real drama of the soul. Three times the memory reaches out and yet again loses the hoped-for good. The simple Pauline sentence “Hold in remembrance Jesus Christ” is given scenic dynamics by the music: the gesture of access is followed by withdrawal – renewed attention and loss again. Musically, we as listeners find ourselves directly involved in the movement of memory and forgetting. It is not until the fourth time that Jesus has arrived, as it were, in memory. And if here he is jubilantly greeted as the Risen One, his movement between death and return is now one with the movement of memory between forgetting and recovering what has been forgotten.

How endangered the memory of the believer is is then made clear in the tenor aria. A memory that only knows the Easter message, that is mere knowledge, does not have the present power that overcomes all doubt. This power comes, as the alto recitative announces, to the “song”, which then appears glorious itself with the chorale “Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag”. The chorale is, in the beautiful formulation in the programme booklet, the “gem” between the doubt recitatives 3 and 5; it is the sustaining centre of the whole cantata. For again uncertainty arises in the connection, and again the resurrection story is closely linked to the drama of memory in the soul of the believer. All those who want to grasp Christ in their memory are in the same situation as the unbelieving Thomas, even more affected by restlessness and irritation than he, for his eyes have seen the Saviour, but the believer born after him must visualise him inwardly – in accordance with Jesus’ words: “Blessed are those who do not see and yet believe”. The dialogue between the chorus and the bass in the sixth stanza is the tension in the drama of remembrance between the nervousness of an everyday consciousness driven by distractions, worries, fears and hopes on the one hand and the reassurance in an all-encompassing, overarching memory of the true on the other. Is the talk of Christ as “Prince of Peace” and “Emergency Helper” then to be understood in such a way that everything troubling, the temptations and grievances, are now left behind, forgotten? Or is the hectic hustle and bustle that the chorus and orchestral parts demonstrate ‘suspended’ in the higher calm of religious remembrance – suspended in the beautiful Swabian double meaning of the word, which means to preserve and to lift up? I would like to understand the end of the cantata in this sense. Its last word is “cry out”. The hardship, the contradictions and the tensions of life are not eliminated, but gathered together in a memory which, as the memory of the Highest, is at the same time able to settle their dispute. If this interpretation is correct, then the beautiful Memoria sentence by Jean Paul also applies to our cantata: “Memory is the only paradise from which we cannot be expelled. Perhaps with the shift of emphasis that memory is the medium through which we can always return to paradise. As the son of a pastor and organist, Jean Paul knew well what it means to recover Christ in memory in a Protestant musical service.

Since I am a Germanist, let me conclude with a reference to the most important poet of memory in German literature: Friedrich Hölderlin. The last two great poems Hölderlin wrote before his collapse and admission to the psychiatric hospital in Tübingen in 1806 are entitled “Andenken” and “Mnemosyne” (Mnemosyne means memory, and in Greek mythology it is the mother of the Muses, the origin of the arts). Five years earlier, he had completed “Bread and Wine”, his famous communion poem, which, however, had a rather alienating effect on orthodox Christians and still does today. For the god recalled here is the Greek god of wine, Dionysus. But Christ also appears at the end of the text; for Hölderlin, he is the “brother” of Dionysus, or more precisely: a half-brother, fathered by the divine “father” (to whom Zeus and the biblical god merge), each with a different woman. Christ and Dionysus are the intermediary gods between heaven and earth who were carried by mortal mothers. They both experienced death in themselves and were resurrected. And after having lived in the midst of human beings, they have departed from them with the promise that they will one day return and create a heavenly festival of peace and interpersonal reconciliation. In this, they move closer together for Hölderlin. That is why he can base his critique of the present on their names and their stories. For according to Hölderlin, we, the people of the modern age, live in the time of their most extreme absence, an epoch of increasing forgetfulness of the “divine”, as Hölderlin calls it across religions. In his poem “Der Archipelagus” (The Archipelago), as early as 1800, Hölderlin highlights the infirmities of an unleashed growth society in which people encounter each other primarily as economic subjects in competitive battles and wear themselves out in them, without ultimately being able to make sense of this “hustle and bustle”:

“But woe! It walks in night, it dwells as if in the Orkus,

Without divinity our sex. To their own hustle and bustle

They are forged alone, and in the roaring workshop

Hear every one and much the savages work

With mighty arm, restless, yet always and always

Fruitless, like the Furies, remains the toil of the poor.”

In this night of eclipse of meaning, in which modern humanity lives according to Hölderlin, it is important to keep the “memory of the divine” alive: “Holy memory (…), to stay awake at night”, it says in “Bread and Wine”. Memory of the divine means, as Hölderlin explains in an essay, to preserve the awareness that there is “a more than mechanical connection” between people. One could also say: a more than functional-economic connection. The hubris of boundless exploitation of nature and infinite increase in performance in accelerated economic competition (“and much work the savages”!) should come to an end in favour of a society that would once again understand itself as a community, as a community in solidarity. For Hölderlin, the task of his Poe was to promote such communality by remembering the unifying power of religious world views. That is why he called his last poems before the outbreak of the illness “Gesänge”. They are songs that the poet, as it were as a pre-singer, now sings alone, but which are to become congregational songs so that everyone would feel the presence of Dionysus and Christ, those “gods of joy” that unite people in intoxicating rapture and love. That this happens where great art takes hold of an audience, where groups of people collectively reflect on something higher, “more than mechanical”, can be experienced again when listening to the cantata “Halt im Gedächtnis Jesum Christ”. Perhaps Hölderlin’s touchingly unrealistic hope that we would all one day become “singing” is therefore not entirely groundless after all. I will conclude by quoting the wonderful, enigmatic verses from Hölderlin’s song “Peace Celebration”, in my eyes the most beautiful poetic counterpart to that musical peacemaking in the restless soul that marks the end of our cantata:

“Much has from tomorrow,

Since we are a conversation and hear from each other

Experienced man; but soon we are song.”

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).