Wachet! Betet! Betet! Wachet!

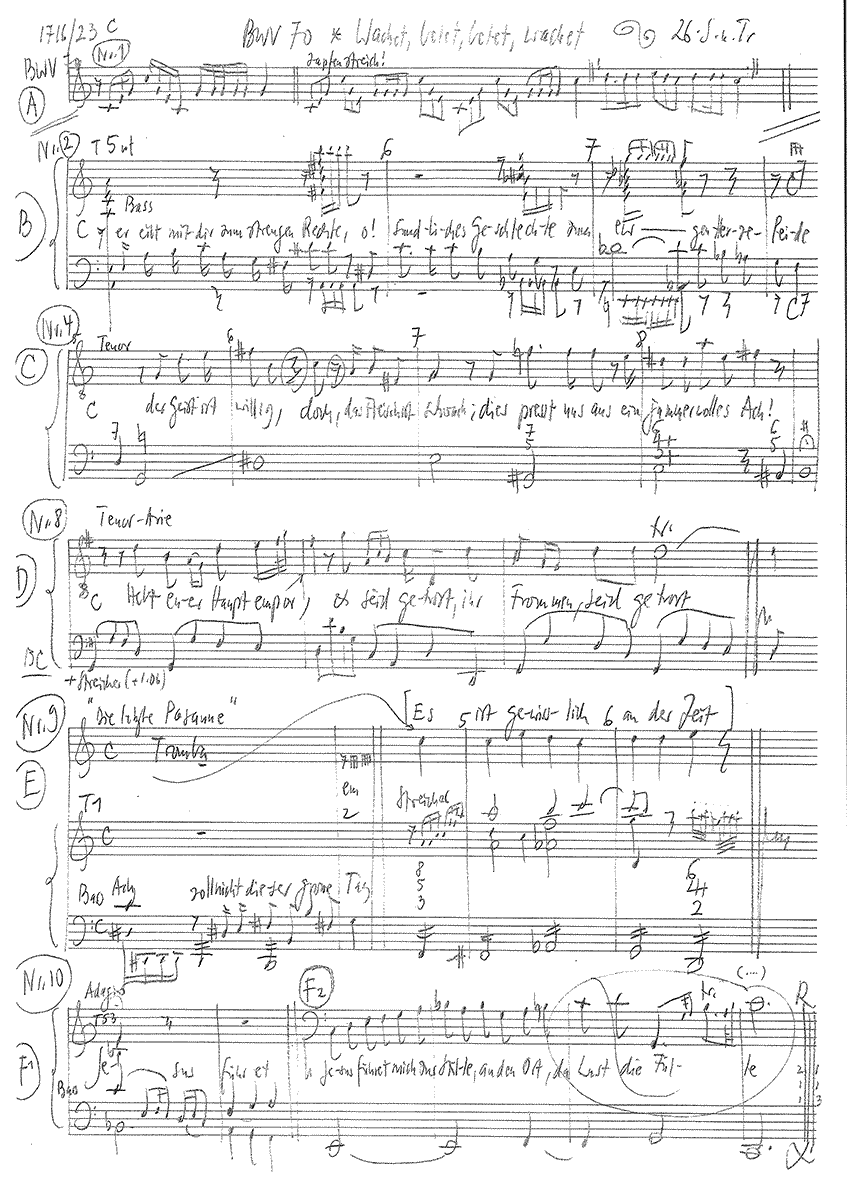

BWV 070 // For the Twenty-sixth Sunday after Trinity

(Watch ye, pray ye, pray ye, watch ye!) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, tromba, oboe, bassoon, violoncello, strings and continuo

Originally composed in Weimar for the Second Sunday in Advent, Bach reworked cantata BWV 70 in Leipzig in 1723, moving it to the 26th Sunday after Trinity and thus to the end of the church year, a shift that was facilitated by the eschatological theme of both Sundays. In this revision, Salomo Franck’s Weimar Libretto of 1717 was extended by three recitatives, and a further chorale movement (no. 7) was added to complete the work’s transformation into a two-part “sermon cantata”.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Guro Hjemli, Susanne Seitter, Gunta Smirnova, Noëmi Sohn Nad

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Kazuko Nakano, Liliana Lafranchi, Damaris Rickhaus

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Walter Siegel

Bass

Oliver Rudin, Manuel Walser, Tobias Wicky, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Christoph Rudolf, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Krone

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Dominik Melicharek

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Jörg Andreas Bötticher

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Jan Assmann

Recording & editing

Recording date

11/22/2013

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 3, 5, 8, 10

Salomo Franck, 1717

Text No. 11

Christian Keymann, 1658

Text No. 2, 4, 6, 7, 9

Poet unknown

First performance

Twenty-sixth Sunday after Trinity,

21 November 1723, Leipzig

In-depth analysis

The opening chorus sets a scene of dramatic tension that is characterised by fanfare motives and contrasting energy: while the gesture of “Wachet!” (watch ye!) is somewhat brusque in style, the extended “Betet!” (pray ye!) figure takes shape as a long, beseeching moment of tonal suspension against the looming orchestral passages. Here, the sweeping gestures and purposeful harmonic development lend the movement an expansive character that anticipates the cantata choruses of Bach’s sons. In the more relaxed middle section, however, the disparate passages and unexpected developments evoke a sense of uncertainty: the end of the world will come, yet we know not the day or hour, and must be prepared.

The bass accompagnato is set as a great procession in which a baroque representation of justice is present in the brilliancy of the trumpet calls. That the collapse of earthly order represents not only an end, but also a promise for “God’s own elected children”, is implied in the arioso passages. The alto aria then responds with a mellifluous cello cantilena, which is assigned to the organ in an alternative (possibly later) version. In this movement, the urgency to repent in face of the “final hour” (interpreted here as deliverance from the inner “Sodom and Egypt” of sin and bondage) is not declared as a thundering prophecy, but rather as a poignant, brotherly warning. Yet the struggle of the “weak flesh” to remain true to this “heavenly longing” is felt all too clearly in the tenor recitative, whose unsparing soul-searching culminates in an imperfect cadence on the words “sorrowful alas!” The following soprano aria then unfolds as music of great fortitude and strength, with resolute unison strings layered over an energetic continuous bass: despite all derision and scorn, “Christ’s word… stands unshaken” – a statement Bach underscores with high long-notes. Indeed, the certainty of experiencing the vision of the saviour inspires even the continuo to a brief, ascending passage of elation (“for it will and has to happen!”). Accordingly, the tender tenor recitative offers a glimpse of the “heavenly Eden”, ere the chorale “Now be glad, O thou my spirit” (added for the Leipzig version) closes the first part of the cantata in flowing, triple metre.

The aria “Lift high your heads aloft” opens the second part of the work with a long overture and sonorous string setting that radiates a warm sense of fullness and trust. Seldom has a two-part cantata fulfilled its function as the framework for a sermon so effectively: the comforting promise of redemption, so potently elucidated by the predicant, is musically interpreted here in a powerful tenor solo that, although mellifluous, also reveals a confident hero. Indeed, no triumphant commander holds forth, but rather a sanguine coach who ensures his charges are prepared for each and any difficulty.

Nevertheless, “doubting, fear and terror” make a final return, and the “child of sin” in the ensuing bass accompagnato can barely resist the temptation crowding in from all sides. Consolation, however, is at hand through the integration of the chorale melody “Es ist gewißlich an der Zeit, daß Gott der Herr erscheinet”, sounded wordlessly by the trumpet – a bold innovation that works not only to transform the movement’s form: indeed, with the chorale’s Cantus Firmus and its message of Christ’s return throning over the racing orchestra and floundering vocal part, the chaos of the Last Judgement as part of the divine plan is thrown into sharp relief, lending Bach’s setting of this scene a theological dimension.

The much slower aria “O most blest refreshment day” is music of inspired surrender that calls to mind parts of Handel’s oeuvre and Bach’s bass cantatas. Even the recurring signal motives of the presto middle section are no longer cause for distress, but instead proclaim ecstatic joy – all fear has been overcome; the Judgement can be emphatically affirmed. A misleading caesura – which sees the “End” as simply a passage to true life – then leads back to the adagio, whose suspended movement is a masterly musical reflection on the word “stillness”. After this grandiose triptych of fear of death, transition and arrival, one could hardly expect the work to scale further heights. Yet Bach masters even this challenge with apparent artistic ease: by suffusing the closing chorale verse with an all but surreal light through three obbligato violins, he evokes a tender forcefulness that longs to mercifully redeem the most unrepentant souls. The selected hymn text “Not for world, for heaven not” makes all too clear that the final purpose is not a measurable price, nor even the attainment of heaven, but only the arrival in God’s hands. Indeed, although this outcome could not have been foreseen at the cantata’s opening, it provides a theologically correct as well as philosophically profound solace, for which we may well envy Bach’s Weimar and Leipzig congregations…

Libretto

Erster Teil

1. Chor

Wachet! betet! betet! wachet!

Seid bereit

allezeit,

bis der Herr der Herrlichkeit

dieser Welt ein Ende machet.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Erschrecket, ihr verstockten Sünder!

Ein Tag bricht an,

vor dem sich niemand bergen kann:

Er eilt mit dir zum strengen Rechte,

o! sündliches Geschlechte,

zum ewgen Herzeleide.

Doch euch, erwählte Gotteskinder,

ist er ein Anfang wahrer Freude.

Der Heiland holet euch, wenn alles fällt und bricht,

vor sein erhöhtes Angesicht;

drum zaget nicht!

3. Arie (Alt)

Wenn kömmt der Tag, an dem wir ziehen

aus dem Ägypten dieser Welt?

Ach! lasst uns bald aus Sodom fliehen,

eh uns das Feuer überfällt!

Wacht, Seelen, auf von Sicherheit

und glaubt, es ist die letzte Zeit!

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Auch bei dem himmlischen Verlangen

hält unser Leib den Geist gefangen;

es legt die Welt durch ihre Tücke

den Frommen Netz und Stricke.

Der Geist ist willig, doch das Fleisch ist schwach;

dies presst uns aus ein jammervolles Ach!

5. Arie (Sopran)

Lasst der Spötter Zungen schmähen,

es wird doch und muss geschehen,

dass wir Jesum werden sehen

auf den Wolken, in den Höhen.

Welt und Himmel mag vergehen,

Christi Wort muss fest bestehen.

Lasst der Spötter Zungen schmähen;

es wird doch und muss geschehen!

6. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Jedoch bei dem unartigen Geschlechte

denkt Gott an seine Knechte,

dass diese böse Art

sie ferner nicht verletzet,

indem er sie in seiner Hand bewahrt

und in ein himmlisch Eden setzet.

7. Choral

Freu dich sehr, o meine Seele,

und vergiss all Not und Qual,

weil dich nun Christus, dein Herre,

ruft aus diesem Jammertal!

Seine Freud und Herrlichkeit

sollt du sehn in Ewigkeit,

mit den Engeln jubilieren,

in Ewigkeit triumphieren.

Zweiter Teil

8. Arie (Tenor)

Hebt euer Haupt empor

und seid getrost, ihr Frommen,

zu eurer Seelen Flor!

Ihr sollt in Eden grünen,

Gott ewiglich zu dienen.

9. Rezitativ (Bass)

Ach, soll nicht dieser große Tag,

der Welt Verfall

und der Posaunen Schall,

der unerhörte letzte Schlag,

des Richters ausgesprochne Worte,

des Höllenrachens offne Pforte

in meinem Sinn

viel Zweifel, Furcht und Schrecken,

der ich ein Kind der Sünden bin,

erwecken?

Jedoch, es gehet meiner Seelen

ein Freudenschein, ein Licht des Trostes auf.

Der Heiland kann sein Herze nicht verhehlen,

so vor Erbarmen bricht,

sein Gnadenarm verlässt mich nicht.

Wohlan, so ende ich mit Freuden meinen Lauf.

10. Arie (Bass)

Seligster Erquickungstag,

führe mich zu deinen Zimmern!

Schalle, knalle, letzter Schlag,

Welt und Himmel, geht zu Trümmern!

Jesus führet mich zur Stille,

an den Ort, da Lust die Fülle.

11. Choral

Nicht nach Welt, nach Himmel nicht

meine Seele wünscht und sehnet,

Jesum wünsch ich und sein Licht,

der mich hat mit Gott versöhnet,

der mich freiet vom Gericht,

meinen Jesum lass ich nicht.

Jan Assmann

“When will the day come?”

The cantata “Wachet! Pray! Pray! Wachet!” appeals to believers to be ready for the day when God will deliver his faithful from this world of oppression and injustice.

“When will the day come when we shall go forth

out of the Egypt of this world?”

So says the first aria of the Bach cantata “Wachet! Pray! Pray! Watch!”. What do we mean by the “Egypt of this world“? And what day are we thinking of here? As we know, the children of Israel left Egypt more than three thousand years ago when God freed them from the slave house through Moses. They had migrated from Canaan into Egypt 400 years earlier due to a famine and had multiplied there into a large people, so that the Egyptians became fearful and oppressed the Israelites in the worst ways. This is what is written in the Book of Exodus, in the 2nd Book of Moses, which thus blackened the image of Egypt in cultural memory for all time as the epitome of exploitation, injustice and oppression. For the lyricist Salomon Franck, this whole world is seen as one Egypt, “a house of slaves”, from which a coming day will free us all. This is the Day of Judgement, when at the end of the world the pious will be delivered into paradise and the sinners thrown into hell. The Exodus from Egypt is taken here as a prefiguration of the end of the world. Just as God once delivered the Israelites from Egyptian bondage, so on the Last Day he will deliver his faithful from this world of oppression and injustice.

Salomon Franck wrote this cantata for the 2nd Advent, and Bach performed it in Weimar in 1717 on the 2nd Advent. But in Leipzig, where he wanted to perform it again in 1723, music on Advent Sundays was out of the question. So he had to take another Sunday and chose the 26th Sunday after Trinity. Bach’s sacred cantatas are all written for a very specific place in the church year. And in the Christian church year, all Sundays and feast days have a very specific meaning. The church year gives meaning and form to empty time, so that it not only passes but also brings something back, namely the memory of the sacred history that God has in store for humanity. We need to know this meaning if we want to understand the text and music of Bach’s cantatas. This raises the question of what the 2nd Advent has to do with the end of the world, and how Bach was able to rededicate a cantata written for the 2nd Advent to the 26th Sunday after Trinity.

The Sabbath

Before I go into this question, however, I would like to emphasise in general terms the magnificence of the idea of making passing time the medium for making present a sacred, highly significant history. The Christians took over this idea from the Jews. They introduced the Sabbath and with it the week, a cultural achievement that has since become established throughout the world. That was in the time of the Babylonian exile, when after the loss of land, kingship and temple, time seemed to the Jews to be the only dimension in which the boundary between the sacred and the profane could still be drawn in a foreign land and the special identity of the chosen people could be experienced in ritual performance. The world of that time knew holidays, but no Sundays in the sense of a period of rest recurring at regular short intervals.

In the cycle of the year, the Jewish community read through the entire Torah (the 5 books of Moses) and corresponding passages from the prophetic books on the Sabbath and festival days using selected passages. The Torah deals with the history, first of humanity, then of Israel, from creation to the death of Moses. This sacred history is liturgically recapitulated in the course of the year and hermeneutically illuminated from the prophetic books. The Sabbath thus combines the cyclical and the linear experience of time. The cyclical lies in the repetition of the formal sequence of events, the linear in the reading and interpreting of sacred history. Christianity has adopted this procedure in the rite of the church year and has enormously expanded and developed it in the course of its history.

The church year

The church year is divided into two halves. The first half, from Advent to Pentecost, recapitulates the life of Jesus from the birth to the Ascension and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, i.e. the institution of the Church. Until then, the church year proceeds in a linear-chronological fashion, just like the Jewish working through of salvation history. The second half of Trinity until the 26th, sometimes 27th Sunday after Trinity takes up individual themes from the Gospels. The Torah and the Prophets are replaced by the Gospels and Epistles for Christians, but still thematically appropriate passages from the Old Testament, as well as songs, prayers and sermons that place the theme in wider contexts. As a result, the time that is ritually visualised in the Christian church year has become three-layered: the most important time layer, the life of Jesus, to which the gospel and epistle readings refer, lies in the middle between the Old Testament history of salvation, which reaches back to creation, and the presence of the congregation, as echoed in the songs, prayers and sermons.

In mundane everyday time, one day is like another, deriving its random meaning from the transactions and adversities of life. Time appears here as pure transience. In the church year, however, which is repeated annually and in this sense eternal, each Sunday and feast day has its own special significance in terms of salvation history, which is derived from the corresponding gospel and epistle readings, and which is illuminated in all directions in the respective celebration through songs, prayers and sermons.

The end of the world in twofold illumination

The 2nd Advent, for which Franck and Bach composed the cantata “Wachet! Pray! Pray! Wachet!”, is, in the semantics of the church year, the sign of the expectation of the coming of Christ. However, this Sunday is not about the birth of the Saviour, but about his return at the end of time, i.e. actually about the end of the world and the Last Judgement. The Gospel reading for this day is Luke 21:25-34:

“And there shall be signs in the sun, and in the moon, and in the stars: and upon the earth men shall be afraid, and shall tremble; and the sea and the multitudes of waters shall roar; and men shall faint for fear, and for waiting of things to come upon the earth: for the powers of heaven also shall be shaken. And then shall they see the Son of man coming in a cloud with power and great glory. And when these things begin to come to pass, then look up, and lift up your heads, because your redemption draweth nigh.”

“Lift up your heads and be of good cheer, ye godly ones!” sings the tenor in the third aria of the cantata.

Bach rededicated the cantata for the 26th Sunday after Trinity in Leipzig in 1723. This is the last Sunday of the church year before it begins anew on 1 Advent. The reading for this Sunday was Matthew 25:31-46 and 2 Peter 3:3-23. These are two texts that also deal with the end of the world and the Last Judgement, but now not under the sign of salvation, but of fear and trembling. Matthew states:

“But when the Son of man shall come in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, then shall he sit upon the throne of his glory, and before him shall be gathered all nations. And he shall separate them one from another, as a shepherd divideth the sheep from the goats, and shall set the sheep on his right hand, and the goats on his left.”

This is how Michelangelo depicted it in the Sistine Chapel. In Peter it is said:

“But the day of the LORD will come as a thief in the night, in the which the heavens shall pass away with a great noise; and the elements shall melt with fervent heat, and the earth and the works that are therein shall be burned up. (…) But we wait for new heavens and a new earth according to his promise, in which righteousness dwells.” (2 Peter 3:10-13)

Both days, the end and the beginning of the church year, are thus marked by the same end-time mood. The coming of the Messiah is near, and with him the end of the world, the Last Judgement, the redemption of the pious and the punishment of the damned. Bach was thus able to adopt the Weimar cantata for Leipzig without changing a single word of Salomo Franck’s texts for the opening chorus and the four arias, which deal with the Last Day. However, this day on the 2nd of Advent is above all under the aspect of redemption. This is already made clear by the triumphal opening Sinfonia, in which the trumpet of the Last Judgement calls the pious to joyful expectation of redemption. Bach therefore had to add the aspect of wrath and terror to the Advent cantata in order to set it up for the much darker illumination in which the end of the world appears on the 26th Sunday after Trinity.

The Accompagnato and the Terrors of the End of the World

For this purpose, he ordered four recitatives for the Leipzig version, which he inserted between the arias. Bach used two highly dramatic bass accompagnati to express the horrors of the Last Day. The accompagnato, the orchestral recitative, is the most dramatic and expressive of the five musical forms that can be used in a cantata, alongside the entrance chorus, the final chorale, the da capo aria and the so-called secco, the recitative accompanied only by the continuo. The first Accompagnato of our cantata follows on from the entrance chorus and is entirely in the spirit of the dies irae, calling sinners to repentance, but promising the pious eternal bliss with a sudden turn to the gentle in sweet melismas and coloratura. The second Accompagnato, which precedes the last aria and the final chorale, is particularly expressive and dramatic. Octavating and repeating sixteenths in the bass, wild cascades of thirty-seconds in the violins paint collapse and crash, and above the tumult the trumpet of the Last Judgement intones the chorale “Es ist gewißlich an der Zeit”, which the hymnal assigns to the 26th Sunday after Trinity:

“It is surely time,

that the Son of God will come

in his great glory,

To judge the wicked and the righteous.

Then the laughter will become deu’r,

when all shall be consumed in fire,

as Peter wrote of it.”

Here again it is a question of salvation and damnation. The two Accompagnati thus bring out the ambivalence of the Last Day: for some it means the end with terror, weeping and gnashing of teeth, for others the longed-for beginning of eternal peace and salvation. End and beginning – that is the mood in these late, gloomy days of November before the 1st of Advent. The church year has come to an end and man thinks both of his own end, death, and of the end of time, which promises eternal life to some and eternal damnation to others. But this threefold end is contrasted with a twofold beginning: the new church year with Advent and Christmas, and the resurrection at the end of the world time with eternal life in the new world of God’s kingdom, of which Christians dream. Judgment Day comes like a thief in the night, suddenly, unexpectedly, one must be constantly ready for it. Being ready is everything, to speak with Hamlet. Every end could be the last; you don’t know if it will go on again. The only thing that helps is to watch and pray, pray and watch. “Watch and pray”, Jesus said in the Garden of Gethsemane, “on the night he was betrayed”, “watch and pray, lest you fall into temptation!” (Matthew 26:41). Do not fall asleep in the “Egypt of this world”, do not resign yourself to betrayal and violence, injustice and oppression, even if it is only about the humanisation of the world and not its complete dissolution at the end of days.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).