Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild

BWV 079 // For Reformation Sunday

(God is our true sun and shield!) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, oboe I+II, horn I+II, timpani, strings and basso continuo

Composed for Reformation Day in 1725, cantata BWV 79 (“God is our true sun and shield!”) is conceptually distinct from its more famous relation, BWV 80.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Karoline Echeverri, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone, Katya Polin

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Corno

Olivier Picon, Thomas Müller

Timpani

Martin Homann

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz, Stefan Stirnemann

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Elisabeth Binder

Recording & editing

Recording date

28.04.2017

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Psalm 84:12

Text No. 3

Martin Rinckart (1636)

Text No. 6

Ludwig Helmbold (1575)

Text No. 2, 4, 5

Author as yet unknown

First performance

31 October 1725

In-depth analysis

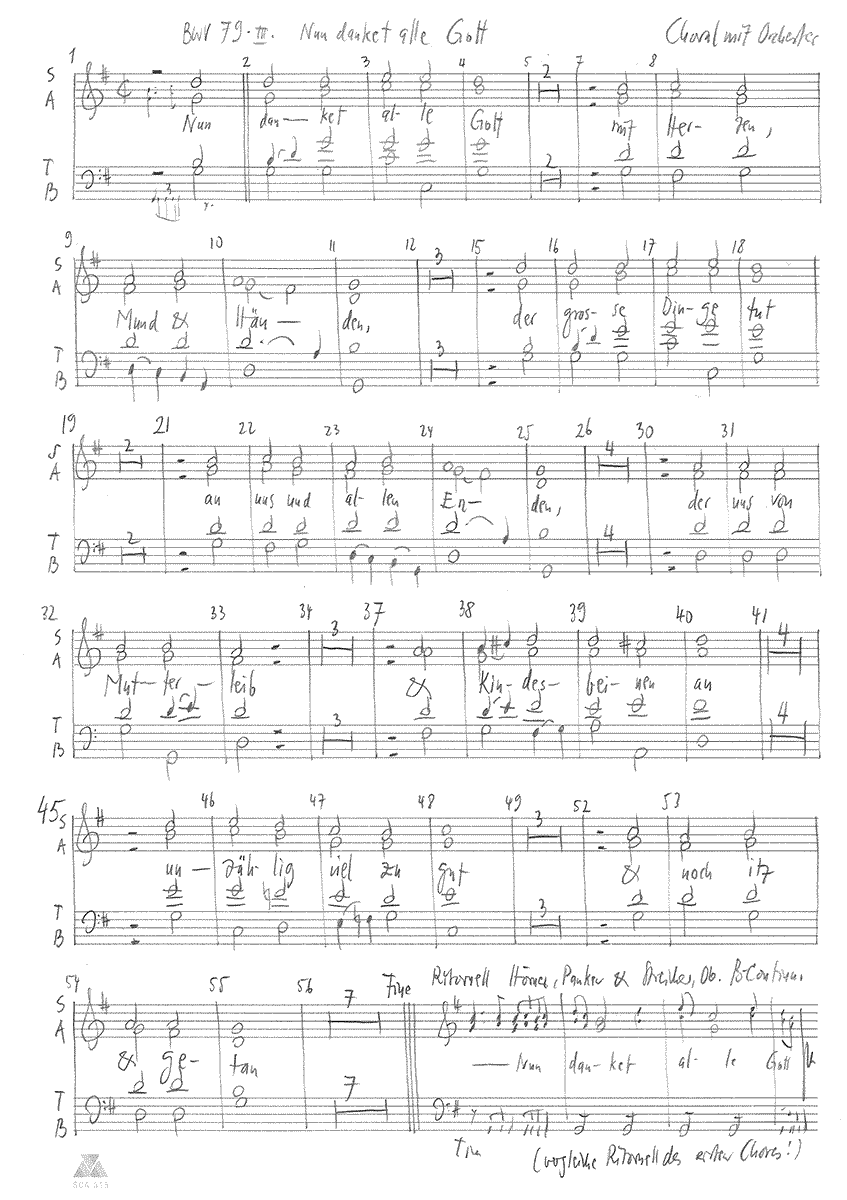

The opening chorus, orchestrated with two horns, timpani, woodwinds, strings and four vocal parts, is not based on a wellknown chorale hymn, but instead presents splendid celebratory music in masterful form; here the light pulsing rhythm of the orchestra provides for a structural constancy, rather like a well-regulated valve, which could nonetheless cause the boiler to burst at any time. Free imitation and block-like sections alternate with colourful concertante-style passages that merge seamlessly into an extended doublefugue on the dictum’s third phrase “he will no worthy thing withhold from the righteous”. The setting of this key phrase echoes elements of the orchestral prelude before flowing into a magnificent quasi-reprise that surprisingly culminates in a serene restatement of the full dictum. Indeed, the listener gains the impression that Bach went to considerable lengths to present the text as clearly as possible; at the same time, Luther’s admiring statement on Josquin – that he is the only composer where the notes have to do as he says, and not the other way around – seem equally applicable here to Bach. In the version on our recording, the chorus is performed by an ensemble of only four concertists – a variant that is undoubtedly plausible considering the performance conditions of Bach’s day; indeed, this practice may well have been the norm.

Aria number two, set for alto voice, oboe and continuo, proffers an elegantly formulated extension of the opening dictum. In this compact setting, the music blissfully expresses the confidence and refuge found in God’s love, and thus the somewhat stilted text of the closing lines (“Though our foes their arrows sharpen, And the hound of hell should howl”) slips by more or less unnoticed.

The chorale “Now thank ye all our God”, a veritable hymn of celebration, then provides for a shift to the worldly sphere of congregation and community; in our recording, we therefore included the rousing voices of the audience. The distinctive horn ritornello of the introductory movement is employed as an interlude, thus recalling this theme for the listener and establishing a charming sense of structural continuity. The bass recitative “Thank God we know it, the proper path to blessedness”, then reveals a confessional polemic of the “us against them” variety: those not adhering to the right path of Lutheran faith are blinded. In view of the emphasis given to Christ as the only intercessor between humans and God, it is fair to presume that the “alien yoke” refers to the Roman Papal Church and its priesthood that was abolished by Luther. This is followed by a distinctive vocal duet in which the soprano and bass take up the ritornello theme of the first movement to declaim the words “God, O God, forsake thy people nevermore!”, while the unison violins interject with a distinctive motive of octave leaps, rather like an ostinato continuo part, to provide solo interludes. In the resulting solemn yet feisty miniature, the bluster of the enemy is broken by the child-like determination of the vocal protagonists.

The closing chorale, which retains the theme of preserving the “true path”, is lent a spirit of communal rejoicing by the addition of horn and timpani parts. The vibrant combination of strings, woodwinds and voices is particularly audible with the small vocal ensemble – in Bach’s vivid settings, the instruments are assigned an equal role in expressing the import of the text.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild.

Der Herr gibt Gnade

und Ehre, er wird kein Gutes mangeln

lassen den Frommen.»

2. Arie (Alt)

Gott ist unsre Sonn und Schild!

Darum rühmet dessen Güte

unser dankbares Gemüte,

die er für sein Häuflein hegt.

Denn er will uns ferner schützen,

ob die Feinde Pfeile schnitzen

und ein Lästerhund gleich billt.

3. Choral (mit Publikum)

Nun danket alle Gott

mit Herzen, Mund und Händen,

der große Dinge tut

an uns und allen Enden,

der uns von Mutterleib

und Kindesbeinen an

unzählig viel zugut

und noch itzund getan.

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

Gottlob, wir wissen

den rechten Weg zur Seligkeit;

denn, Jesu, du hast ihn uns durch dein Wort gewiesen,

drum bleibt dein Name jederzeit gepriesen.

Weil aber viele noch

zu dieser Zeit

an fremdem Joch

aus Blindheit ziehen müssen,

ach! so erbarme dich

auch ihrer gnädiglich,

daß sie den rechten Weg erkennen

und dich bloß ihren Mittler nennen.

5. Arie (Duett Sopran, Bass)

Gott, ach Gott, verlaß die Deinen

nimmermehr!

Laß dein Wort uns helle scheinen;

obgleich sehr

wider uns die Feinde toben,

so soll unser Mund dich loben.

6. Choral

Erhalt uns in der Wahrheit,

gib ewigliche Freiheit,

zu preisen deinen Namen

durch Jesum Christum. Amen.

Elisabeth Binder

Sun Reflection

“Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild” (BWV 79) invites us to reflect on the place of nature in the cantata works of the Thomaskantor. What is the relationship between the beauty of art and the beauty of nature? What significance does sunlight have at all for our understanding of beauty? Anyone who asks the question about Bach’s perception of nature should also re-read Franz von Assisi, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Gottfried Keller.

Who of you, or to include me: who of us has ever experienced a sunrise? I mean really experienced. We have probably just experienced one, with the opening movement of today’s cantata (BWV 79), a gloriously sonorous and songful one: “God the Lord is Sun and Shield”.

But I don’t mean this one, not yet this musically symbolic one. I would like to take a little diversions. In the hope of bringing something from this diversions for the understanding of today’s cantata. I mean the rising of the sun, which brings us the day, and which we, busy with our everyday lives, perhaps greet too seldom, as would be appropriate for its significance for our and for every existence on this earth. Which is why we should occasionally think of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Question of Conscience. In his novel fragment Andreas or the United, set in Venice, it is the worldly and mysterious Maltese knight Sacramozzo who, as his life draws to a close, once again poses the question: “Every morning the sun rises on millions, but where among millions is the one heart that rings out purely to meet it?” Not “beating towards”: “sounding towards”!

“Pure”, meaning poetic, is how poetry has often sounded and continues to sound to her from all parts of the world and through all cultures and centuries. One might think of Gottfried Keller, for example, whose novel Der grüne Heinrich (The Green Henry) begins in its first version on an “earliest Easter morning”, shortly before sunrise. And it is on a “rocky mountain”, one will have to think of the Uetliberg, up which the young Heinrich Lee has climbed to bid farewell to the “hitherto never left home” before setting off for Germany, while at the same time committing what Keller writes is the typical “act of a nature cult” for “enthusiastic young men”, namely: to greet the sun, the morning.

“The wide lake merged with the feet of the high mountains into a blue-grey twilight; the snow peaks and horns stood milk-pale in the early morning. As Heinrich stepped to the edge of the forest, the first rose gleam of the approaching sun flashed over the ghostly formations; the morning star still glowed above the last lonely ice altar. Staring at it, our boy made one of those silent, fleeting sighs of prayer which, if they could be put into words, would go something like this: This is very beautiful, O God! I thank thee for it, I vow to do mine also!”

But since the young Heinrich Lee goes to Germany, or more precisely to Munich, with a “heart full of hope and blossoming worldly courage” to become an artist there, the “Meinigen” also contains the confession or the urge to an art that responds to the beauty of nature, which is what makes the sun visible in the first place and makes it shine, responds devoutly, or, to speak with Hofmannsthal: “sounds towards” it. And that, however, is Keller’s own poetics. As it is expressed in the well-known verse from the poem Die Zeit geht nicht:

“There flashes a drop of morning dew

In the ray of sunlight;

A day can be a pearl

And a century nothing.”

Where it then says in a next stanza:

“To thee, thou wonderful world,

You beauty without end,

I too write my love letter

On this parchment.”

“Beauty is nature / Nature is beauty”, Keller noted as a 19-year-old. And immediately afterwards, in youthful pathos, also set art its goal: “Beautiful art is that which has the high aim of ennobling mankind, of showing it the beautiful, the true, the sublime, of awakening its sense for nature, of depicting vice in all its ugliness – in a word, of raising man to the point for which the Creator intended him.”

There is no mention of a fall from grace here, to be sure. But something must have intervened if man, unlike nature, needs “beautiful art” in order to become the being that his Creator intended to be just as beautiful. The artist would thus, according to the lofty thought, though worlds away from modernity, work together with the Creator on a universal project of beauty.

Did Johann Sebastian Bach not have a similar collaboration and a comparable beauty project in mind for his art? Now we know as little about his relationship with nature as we do about his other views of the world. It is possible that, as far as nature was concerned, he remained within the framework of the Lutheran Church and the Leipzig clergy, which were still not very enlightened in his day.

But within this framework, in which his cantata works also stand, he praised creation many times and with the corresponding musical enthusiasm. And even if we will never be able to prove it, it seems to us that the ravishing variety of his cantatas, apart from all the other inspirations, musical and theological, which may have benefited his genius, would have been inconceivable without the pious and joyful idea of a creative power at work in the variety and harmony of nature and the cosmos. Who knows whether he did not have in mind the full-voicedness of God’s creation, absolutely exemplary, absolutely inspiring, when he aspired to the “full-voicedness” of his art of counterpoint, of which his son Carl Philipp Emanuel once spoke. When, in any case, the second cantata Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes (BWV 76), with which he made his debut as Thomaskantor in the summer of 1723, contains the astonishing phrase: “Natur und Gnad redt alle Menschen” (Nature and grace address all people), this could almost be understood as a kind of programme: “Natur und Gnad” (Nature and grace).

But the latter, grace, now leads me to the second part of my reflection on the sun, and from there back to today’s cantata. But I would also like to take a slight diversions here. It is about a much older poet: Francis of Assisi, who is certainly not the first to have praised a symbol of God in the sun, but we can put him at the beginning with his Laudato si, his Canticle of the Sun. Right at the beginning it says of the Italian masculine and therefore fraternal sun:

“Laudato si – Praise be to you, my Lord, with all your creatures,

especially the Lord, Brother Sun,

who gives us the day and through whom you shine for us.

And beautiful is he and radiant in great splendour (cun grande splendore):

Of thee, Most High, an emblem.”

Now here it is quite clearly stated. The sun is not directly worshipped as a deity, as is the case in the actual sun cults, such as the late Roman sol invictus, which was widespread in Rome when Christianity took root there, and from which the Christian Christmas festival then also took the date, namely that of the winter solstice. In the sun, rather, a manifestation of God is worshipped who, in his infinite greatness, is absolutely beyond our comprehension, while at the same time, miraculously, he reveals himself in his creation, and especially in its central star, and so is comprehensible to us.

And here we can make a leap to the poet Paul Gerhardt, who became so important in the Reformed faith and whose songs were already in the Lutheran hymnal in Bach’s time. Among them is the beautiful morning song that Bach also set to music: Die güldne Sonne.

“The golden sun

full of joy and delight

brings our borders

with its shining

a heart-warming, lovely light.

My head and limbs

They lay prostrate,

But now I stand,

“I’m happy and joyful,

“I see heaven with my face.”

There is no doubt that the morning sun, the natural one that we can see on the things of the world and feel on our faces, is really meant. And at the same time, there is already a whole metaphysics in the enchanting phonetic modulation of “borders” to “shine”. A shine comes into the boundaries of our earthly and finite existence. And this in turn becomes a symbol of what is so central to Luther: grace. God’s gracious attention to what he has created and especially to man, who has been tragically removed from creation since the Fall – an attention that is revealed in Christ’s birth, life, death and resurrection, and since then in his Word, the Gospels – brings this “shining” into the world and especially into our needy existence.

The “sun of grace”, the “radiance of grace” is often spoken of in this context in the church hymns and also in Bach, indirectly also in today’s cantata: the statement “The Lord God is sun and shield” is immediately followed by the declaration: “The Lord gives grace and glory”.

“Splendour” and “grace”, then. And here the sun takes on a completely different dimension, one that is actually only now becoming part of salvation history. For this sun, this sun of grace, shines, flashes, sparkles, when it rises, suddenly (for, according to Luther, no mediation is needed, at most that of Christ himself) into our “heart room”, which then also flashes and sparkles, like that “drop of morning dew” in Gottfried Keller. Yes, in baroque exuberance even more so. So it says at the end of the fifth cantata of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio:

“Though such a room of the heart

is not a beautiful hall of princes,

but a dark pit;

but as soon as your ray of grace

shall shine in the same,

it will seem full of suns.”

Here, then, I could say, going back to Hofmannsthal, there is “pure counter-sound”. If this “room of the heart” is open, that is, receptive to the “ray of grace” (which in Luther’s words means nothing other than faith), then it is virtually transformed into sunshine: a luminous affair.

Now Bach knew too well, and we know it too and even better, since our society is not in the least bit attuned to it any more, that this “ray of grace” is usually not too far off. And that the praising, extolling, giving thanks, which today’s cantata is filled with, and which Luther saw so happily embodied in the birdsong, especially that of the nightingale, is not something that is really innate to human beings, something that is by no means self-evident in the self-consciousness, the hustle and bustle of everyday life, the noise of the times.

And this is precisely where I think Bach comes in with his cantatas. He must have had this rather unenlightened, tuneless “heart room” in mind when he sat in his composing room. But not only the “heart room” – also the “ray of grace”. It must have assisted him when the texts, borne by devout fervour but rarely poetic, serving the religious, not the “aesthetic education of man”, were transformed time after time, and perhaps a miracle to himself, into beautiful, vivid music.

And if his contemporaries (critics who already existed at that time) sometimes reproached him for obscuring the beauty of his music through “too much art”, in other words: beauty could also be easier and catchier to have, for posterity and for us today it was probably precisely this “too much” of art that makes it possible for us to experience a spirituality that we know from no other composer. A spirituality that, rooted in the earthly, has something down-to-earth about it, while it often seems to reach for the heavens. And it obviously affects people from other cultures and parts of the world in the same way. It is as if what Bach himself once wrote down really applies: “With devotional music, God is always present with his presence of grace.

And this “always” is undoubtedly true to this day. Until this moment or the next, when we can once again hear how Bach makes this sun rise. Rather: “sounding towards it”.

With splendour and glory: “The Lord God is our sun and shield”.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).