Jesus schläft, was soll ich hoffen

BWV 081 // For the Fourth Sunday after Epiphany

(Jesus sleeps, what should my hope be?) for alto, tenor and bass, (soprano in closing chorale), recorder I+II, oboe d’amore I+II, strings and continuo.

The libretti set to music by Bach for the Sundays after Epiphany speak predominantly of abandonment, angst and resignation. The fundamental Christian belief in the salvation of the soul and the second coming of Christ is marked once every church year in observances which, by their nature, are hard to bear: the joyful days of the birth and epiphany of the Lord are followed all too soon by the harsh realisation of having to rely on our limited human strength – an awareness that is pervaded by a foreboding of the Passion and knowledge of our own mortality. In these texts, the Christian longing for closeness and sureness of heart is invoked by the metaphor of an absent or sleeping Christ. This corresponds to the painful insight that the path to heaven remains beset with adversity.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Guro Hjemli

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Fanny Tschanz

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Luise Baumgartl, Stefanie Haegele

Recorder/Flute

Armelle Plantier, Priska Comploi

Organ

Rudolf Lutz

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rolf Dubs

Recording & editing

Recording date

01/18/2008

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6

poet unknown

Text No. 4

Matthew 8:26

Text No. 7

Johann Franck, 1653

First performance

30 January 1724

In-depth analysis

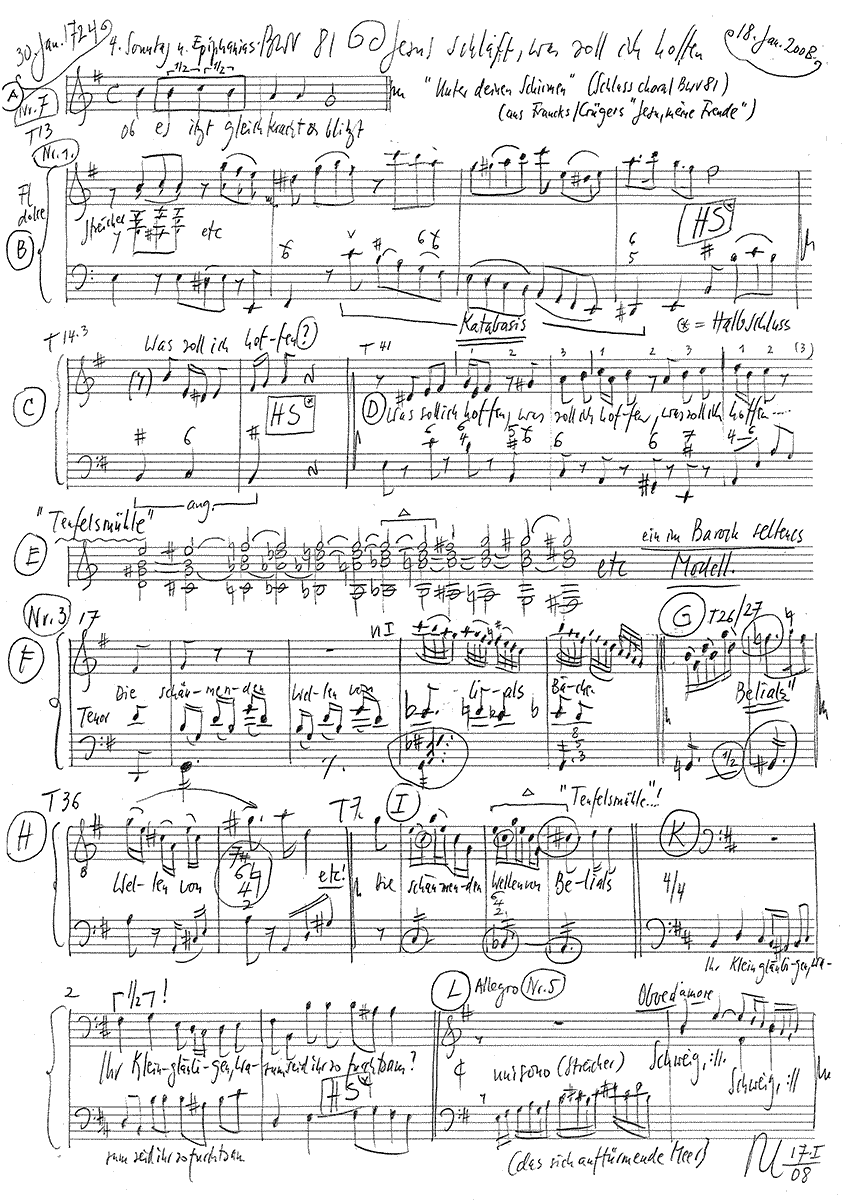

The cantata “Jesus sleeps, what should my hope be?”, first performed on 30 January 1724 as part of Bach’s first Leipzig cantata cycle, unmistakably translates this metaphor into music while the text relates Christ’s delayed intervention during a storm on the Sea of Galilee. In his compositional approach, Bach proved himself to be highly sensitive to the needs of the text. Aside from a quietness evoking sleep, the biblical passage quoted speaks clearly in the first person, lending insight into Bach’s decision to open the work not with a choral movement, but rather an alto aria – the vocal range and timbre that he often employed to personify spiritual inquietude. Although scored pastorally with recorders and strings, the work hardly presents the idyllic scene of tranquillity that so often graced Baroque operas and Christmas cantatas. Far removed from a sense of serenity and certainty, the forlorn music seems to be composed almost entirely of sighs. The frequent pauses of the upper voices bridged only by the throbbing continuo is suggestive of an uneasy Christian heart beating with trepidation in the face of the empty sound evoking the absent Christ. While another composer would have exploited the implications of a tempest at sea solely to paint a dramatic scene, Bach and his unknown poet chose an approach that speaks to the inner soul. Despite the “foam-crested billows” of the tenor aria, the reference to “Belial’s waters” implies that it is the infernal temptations of sin and mortal fear that blow the “winds of sadness” towards Christians. The following arioso, a gentle and steadying continuo ritornello, paves the way for a change in tone: in keeping with good Lutheran tradition, it is indeed those “of little faith” and their lack of trust in God’s word who cause their own despair. Consequently, it is a more fervent than loving Jesus who appears in the aria “Still, O thou tow’ring sea!” to silence the storm (oboes) and the waves (strings) to protect man – God’s chosen child. For this scene, Bach composed raging music invoking Christ’s power to calm the violent sea into long and sustained motionlessness. That Bach, just one and a half years later, set practically identical music to the text “hush, hush then, giddy intellect!” of cantata BWV 178, underpins the interpretation of the sea-storm metaphor in spiritual and moral terms. In the following recitative, the alto, who, like doubting Thomas, has been converted by receiving Christ’s help, brings the thematic scheme of the cantata full circle. A better closing choral for this work than the second verse “Under thy protection, am I midst the tempests, of all foes set free” from Johann Franck’s renowned hymn “Jesu, meine Freude” could hardly have been found.

Libretto

1. Arie (Alt)

Jesus schläft, was soll ich hoffen?

Seh ich nicht

mit erblasstem Angesicht

schon des Todes Abgrund offen?

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Herr, warum trittest du so ferne?

Warum verbirgst du dich zur Zeit der Not,

da alles mir ein kläglich Ende droht?

Ach, wird dein Auge nicht durch meine

Not beweget,

so sonsten nie zu schlummern pfleget?

Du wiesest ja mit einem Sterne

vordem den neubekehrten Weisen

den rechten Weg zu reisen.

Ach, leite mich durch deiner Augen Licht,

weil dieser Weg nichts als Gefahr verspricht.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Die schäumenden Wellen von Belials Bächen verdoppeln die Wut.

Ein Christ soll zwar wie Wellen stehn,

wenn Trübsalswinde um ihn gehn,

doch suchet die stürmende Flut

die Kräfte des Glaubens zu schwächen.

4. Arioso (Bass)

Ihr Kleingläubigen, warum seid ihr so furchtsam?

5. Arie (Bass)

Schweig, aufgetürmtes Meer!

Verstumme, Sturm und Wind!

Dir sei dein Ziel gesetzet,

damit mein auserwähltes Kind

kein Unfall je verletzet.

6. Rezitativ (Alt)

Wohl mir, mein Jesus spricht ein Wort,

mein Helfer ist erwacht,

so muss der Wellen Sturm,

des Unglücks Nacht

und aller Kummer fort.

7. Choral

Unter deinen Schirmen

bin ich für den Stürmen

aller Feinde frei.

Lass den Satan wittern,

lass den Feind erbittern,

mir steht Jesus bei.

Ob es itzt gleich kracht und blitzt,

ob gleich Sünd und Hölle schrecken,

Jesus will mich decken.

Rolf Dubs

“Good and bad elites”

The Biblical Story of the Shutting Down of the Sea Storm and its Significance for Human Leadership

The cantata “Jesus sleeps, what shall I hope for?” was composed – what is now considered certain after a long period of uncertainty on the basis of a booklet found around 1970 in the former Imperial Library in St. Petersburg entitled “Texte zur Leipziger Kirchen-Music” – for the fourth Sunday after Epiphany, 30 January 1724. It was composed during Johann Sebastian Bach’s first year in office in Leipzig. The poet of the libretto, which largely follows the Gospel of the Sunday, is unknown and relies on the description of the stilling of the sea storm as depicted in the Gospels of Matthew, Luke and Mark. The account is of a stormy sea voyage that put Jesus and his disciples in danger, and during which he fell asleep. His slumber, which is understood as absence, frightens the disciples. They fear for their existence. In reference to the tenth Psalm, the remoteness of the Lord is lamented: “Lord, why do you step so far away? / Why do you hide yourself in the time of trouble, / When everything threatens me with a miserable end? / (…).” The danger is described in terms of the foaming waves of Belial’s streams, which threaten to sweep the human soul into the abyss of hell. To be sure, Christians should stand like rocks in such situations and be capable of resistance, even if the waves weaken the forces of faith. In the danger and their distress, the disciples woke Jesus and asked for help. To this he answered them according to Matthew, “You of little faith, why are you so fearful?” or according to Luke, “Where is your faith?” In the cantata, the question according to Matthew’s Gospel is forcefully emphasised as the vox Christi in a form similar to the fugue, and Jesus appears as the Saviour: “Silence piled up sea! / Hush, storm and wind!” The thanks of the saved follows: “Wohl mir, mein Jesus spricht ein Wort, / (…) / und aller Kummer fort.” and the cantata concludes with the second stanza from the hymn “Jesu, meine Freude” (Jesu, my joy) composed by Johann Frank, with which the rescued express their thanks and the certainty that Jesus is helping.

After an initial examination of this text, I very quickly became aware that it has a very different meaning for people of deep faith than for life-oriented, modern people who claim to be believers to a certain extent, but more in an understanding that is more focused on themselves and their own interests. The second group of people is more interesting and problem-ridden. That is why the emphasis of the explanations will be placed on this group.

Anyone who has had the opportunity to visit churches in remote areas in communist countries in the past or to attend church services in poor areas in developing countries today was and is always surprised by the deep faith and hope that people carry within them thanks to their Christian faith. In prayer, they hope for better times, and these hopes can develop in two directions: Either their faith awakens their resilience as they strive to orient their lives towards their Christian principles despite all adversity and to contribute to the liberation of people from poverty and oppression. Or their faith leads them to expect that other institutions and persons committed to Christian thought will help them to implement Christian ideals such as justice and opportunities for personal development. These people want to be led, are afraid of being sidelined by well-meaning people and, especially when the biblical ideas are not realised, turn to leaders – including Christian leaders – who dogmatise the message of the Bible, polarise society and make peaceful coexistence of all people infinitely more difficult. Wherever people hope for biblical miracles, but remain inactive themselves and wait until someone helps, no development can take place. Therefore, the behaviour of the disciples in the storm must not be groundbreaking. Especially where dogmatism and polarisation are already commonplace, resistance is needed: people who have the courage to rebel. But only someone who is neither opportunistic nor egoistic, but who is deeply anchored in his faith and thinks of more than just himself, is suitable for this.

But what about faith today? Who still thinks about the laws of God? And above all: who not only knows what Christianity wants, but who behaves in accordance with divine laws? Of course, purists of empirical research pursue such questions. They tell us lately that people’s faithfulness is on the rise again, not in an institutional setting, but in personal reflection. The only question is: why is people’s behaviour towards each other becoming more and more petty? Why are fewer and fewer people willing to do something for the community? Theoretically, the answer is quickly given: Value education must be strengthened and expanded, whereby – as in many cases – this task is also shifted to the school. Although school experiments in the field of value education (religion or various forms of ethics lessons) have been carried out for several decades with many models, the results of success remain rather modest. In most cases, children and young people absorb religious and moral knowledge, but this has little positive influence on concrete and daily behaviour. It is becoming increasingly clear that religious and ethical values must be built up in the parental home and that this education must begin early in pre-school age. But how is this to be done in view of the increasing indifference of many parents in matters of faith and values? and individual empirical purists add to doubts about faith when they find in studies that people who pray intensively for overcoming an illness or – in the case of childlessness – for conception, achieve their goal with about the same probability as people who do not pray for this.

Such findings are both frightening and depressing. They retain their meaning only as long as things go well. Under difficult life circumstances, help and comfort are sought in faith, which the chorale sings about in a profound way: “Under your shields / I am free for the storms / Of all enemies. / Let Satan rage, / Let the enemy vomit, / Jesus stands by me, / Whether it’s crashing and flashing now, / Whether sin and hell are terrifying, / Jesus will cover me.” Should and can we hope in Jesus and expect that everything will always be all right? Is passivity in faith the right thing? From this question, the text of the cantata can be approached with the problem of human coexistence and social development in our time, which is probably important today. With the question “Jesus is asleep, what shall I hope for?”, the fear of falling into the abyss and the mere expectation that Jesus will lead, the question of the initiative of individual people and their guidance through beliefs and formative personalities becomes significant. Or to put it more pragmatically and politically: do we need elites in our society who lead, and by what values should these elites be guided? The cantata’s answer is clear: “Well done, my Jesus speaks a word, / my helper is awake, / so the storm of the waves, the night of misfortune / and all sorrow must go.” The hope in and expectation of guidance are great. However, they do not mean passivity, but the question from Matthew’s Gospel “You of little faith, why are you so fearful?” can be interpreted as a challenge to stand as a Christian like a rock in the surf and work against the bad.

However, those who advocate leadership and elite today are not following the spirit of the times, which can be characterised by demands such as grassroots democracy and co-determination in all areas. Such ideas could at best be realised if human coexistence were characterised by commonly accepted values. Original Christianity lived under this ideal conception. Today’s society, however, looks different. It is most aptly described by American sociologists: A characteristic of the behaviour of many people in the most diverse areas of life is the Focus on Self, i.e. more and more people see the problems of society only from their personal point of view and increasingly judge possible solutions only from the point of view of their personal values and goals. Therefore, they no longer understand how to deal with the many conflicting goals and how to look for optimal solutions. They prescribe to patent solutions that correspond to their ideas and thus contribute to the further polarisation of society. In addition, the willingness of individuals to fulfil communal tasks is decreasing, but at the same time the expectation of everyone else and of the state community to do something for them is increasing.

The problems associated with this development can no longer be solved in a grassroots democratic manner; instead, an elite is needed that is capable of recognising problems in a differentiated manner and contributing to sustainable solutions.

However, the demand for elites must be differentiated. The term elite is derived from the Latin word eligere, electico and means select and chosen. It is used to characterise people who claim conspicuous public recognition and are able to obtain it thanks to their personal behaviour or build it up thanks to a special constellation of power. However, this public recognition depends not only on personal behaviour and a favourable power constellation alone, but also on what the population determines to be elite. Therefore, elites can never be characterised value-free, but their determination is always based on a value judgement, which leads to the fact that a distinction must be made between good and bad elites.

In view of the problems in our society and the associated conflicts of objectives, only those people who are willing and able to achieve the highest performance in their respective areas of life and profession and who, secondly, are able to take on leadership tasks count as the necessary elite, that is, to motivate other people for reflective performance, to cooperate with them and to challenge them in their activities and behaviour in order to contribute jointly to the solution of conflicting goals, and who, thirdly, are distinguished by human greatness, empathy, modesty and superiority. People who do not belong to the elite or who are only supposed to be elites are those who consider themselves to be among the best simply because of their origin, status or wealth, as well as the group of power seekers who try to impose their rule through skilful power behaviour and opportunism without any consideration for the goals, wishes and demands of other people and without legitimate achievements. This includes not only despots, but also politicians and managers who orient themselves solely on personal claims to power or short-term financial interests and only act with the aim of strengthening their own position of power – and this in the confused idea that in this way they will always belong to the elite.

With the expectation that members of the elite must distinguish themselves through human greatness, empathy, modesty and superiority, one comes close to paraphrasing images of man, not least a Christian image of man. Unfortunately, it becomes apparent, especially in educational research, that if one wants to base the drafting of educational goals or political and economic codes of conduct on images of man, one very quickly slips into the paraphrasing of ideas of behaviour, which not infrequently correspond to novelistic ideas, are often only external behavioural instructions against abuses of all kinds and are usually not consistently justified. A typical example of this is the “economic-ethical” demand of a church institution, which states that a wage system is only fair if the highest salary in a company is no more than 40 times higher than the lowest salary. Even if one vehemently opposes the excesses of individual managerial salaries, this idea is devoid of any psycho- logically based economic reality, and it also lacks any form of legitimacy. unfortunately, the same problems are also evident in the codes of conduct or codes of ethics that have become common today, especially in large companies. They regulate many externalities, provide rules of conduct against abuses and admonish in general terms against human misconduct. What is to be done in these circumstances?

Ideally, all people should return to the four cardinal virtues developed by Aristotle and his successors:

– Prudence as the ability to recognise what I have to do responsibly here and now;

– Fortitude as the ability not to let one’s own timidity distract one from what is recognised as right in prudence;

– moderation as the ability not to be distracted by one’s own covetousness and capriciousness from what is wisely recognised as right and bravely held fast against one’s own timidity (reliability);

– justice as the ability not only to behave rightly towards oneself, but also to allow others to be valid in their qualities and to grant (generously) what is proper to them.

If all people were guided by these cardinal virtues, elites would be unnecessary and a grassroots democratic order in the sense of early Christianity would be possible. And the challenge of Matthew’s Gospel “O ye of little faith, why are ye so fearful?” would become obsolete. However, we are far from this ideal, so elites are needed to lead the human community. But they can only serve the community as good elites if they consciously take on responsibility. Originally, responsibility meant: to stand up for something, to represent something and to justify oneself. Today one could say: I stand by my ideas and my behaviour, I put myself forward because I can stand behind them and I am prepared to openly legitimise any behaviour. I want to be responsible to my fellow human beings with my thoughts and actions, but I don’t only want to understand it in such a way that it goes down well with the public and the media. I am also responsible to my own conscience and – as a Christian – to God, who guides me. Responsible thinking and acting is based on conscientious action. But the question remains open as to how far my responsibility as a member of the elite extends. There is no universally valid, pragmatic answer. However, in his book “Responsibility Sovereignty”, published in 1994, Father Albert Ziegler tries to clarify the problem with a small example: “I throw a stone into the water of a lake. The throwing of the stone causes a circle in the water, which in turn causes further circles, which become weaker and weaker and finally (almost) disappear in the distance. Up to which circle do I have to answer for my stone throwing?” Some think that I am responsible for all circles. But in doing so they take on a responsibility that they cannot bear. No one can bear such a comprehensive responsibility; one would become afraid and unable to act. The others say that they are not responsible for a single circle. This would be irresponsible. Therefore, a middle course between the maximum demand and irresponsibility must always be sought. But how does the good elite find this middle way in everyday thinking, decision-making and action?

The prerequisite for this is the examination of conscience: all people have a conscience that is better or worse depending on the effectiveness of their religious or general value education with regard to desired goals. This education is all the more effective the earlier children come to terms with moral values and the deeper their religious and ethical understanding is. A good elite is therefore expected to be able to independently reflect on emerging ethical problems and to discuss its own decisions of conscience, especially with people affected by them, in order to become aware of the responsibility of its decisions and measures and ultimately to be able to legitimise them. This requires personality traits that are indispensable for the good elite:

– Openness: Those who are not open cannot communicate and be encouraged to reflect.

– Honesty: Those who are not honest cannot be open.

– Predictability: Those who are not predictable do not create a good basis for trust.

– Reliability: Only reliable people take responsibility.

– Credibility: Only credible persons can be reliable.

These personality traits thus characterise the good elite. Scientifically, they are speculative. But they are at least suitable for reflection on one’s own thinking and actions.

This brings us full circle: “Jesus is asleep, what can I hope for?” indicates helplessness. “You of little faith, why are you so fearful?” is the challenge to believe in something, to take action and to stand up for one’s ideas and goals. It would be nice if every single person would follow this call. Unfortunately, today this call is becoming increasingly ineffective: people are torn in their values – not infrequently as a result of manipulation and opportunism – they enjoy the moment instead of taking long-term effective action based on reflected value attitudes right into the personal spheres of life, and they evade when things become unpleasant. Therefore, the longer it takes, the more we need a good elite – and all further social decisions in the direction of egalitarianism remain a socio-political fad that ultimately benefits no one. But do we have the strength and courage to stand like a rock in the surf?

Literature

– Hans-Joachim Schulze, The Bach Cantatas. Introduction to all of Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantatas, 2nd edition, Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2007

– Siegfried Uhl, The Means of Moral Education and their Effectiveness, Klinkhardt, Bad Heilbrunn 1996

– Albert Ziegler, Responsibility Sovereignty, 2nd edition, Josef Schmidt Verlag, Bayreuth 1994

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).