Ich bin ein guter Hirt

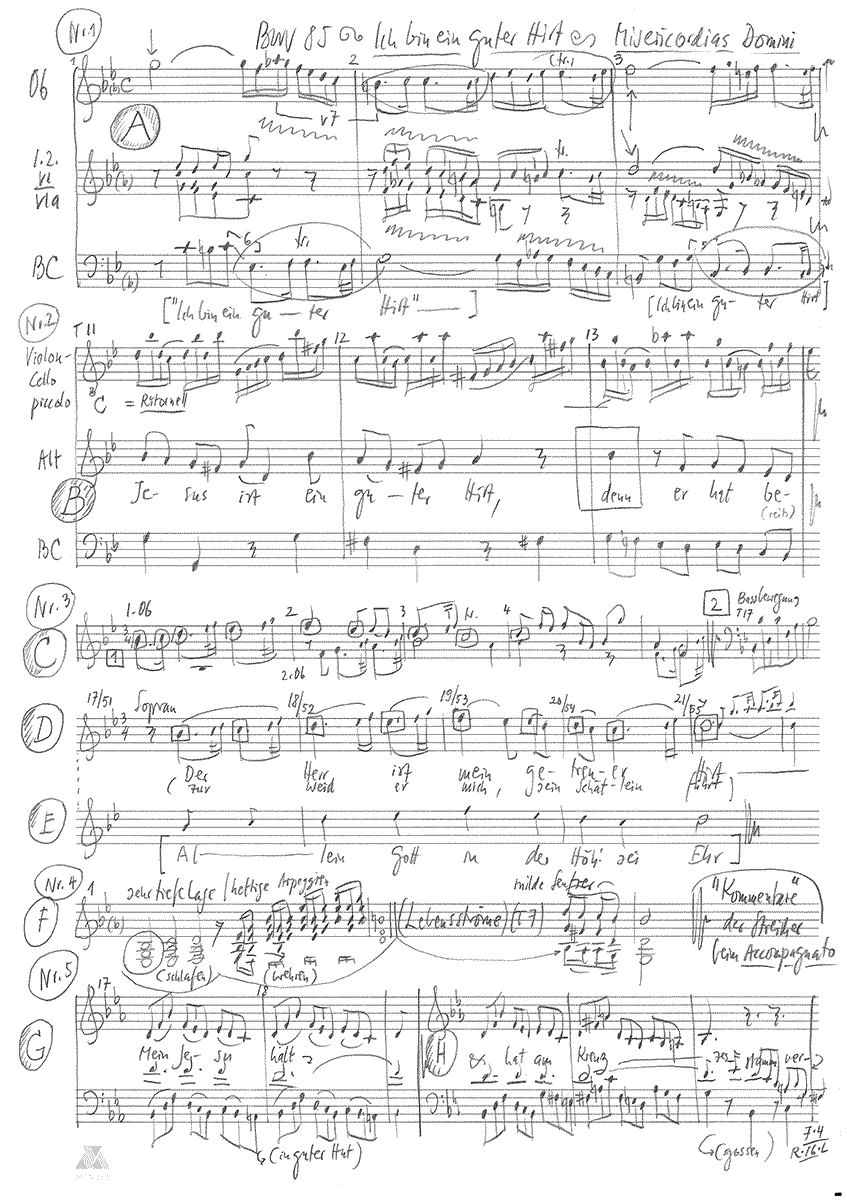

BWV 085 // For Misericordias Domini (Second Sunday after Easter)

(I am a shepherd true) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, oboe I+II, violoncello piccolo, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello piccolo

Martin Zeller

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Peter Wollny, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Peter Wollny

Recording & editing

Recording date

08.04.2016

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

John 10:11

Text No. 2, 4, 5

Poet unknown

Text No. 3

Cornelius Becker, 1598

Text No. 6

Ernst Christoph Homburg, 1658

First performance

15 April 1725, Leipzig

In-depth analysis

Based on the parable of the Good Shepherd (John 10), and composed for the Second Sunday after Easter in 1725, cantata BWV 85 numbers among Bach’s chamber-music style church compositions that have no tutti introductory chorus. Through its combination of expansive oboe cantilena and meditative ensemble setting, the opening aria in C minor – fittingly set for bass as the vox Christi – exudes a concentrated air of earnest and tragic devotion in which the vocal and instrumental motifs are tightly interwoven in their descending figures and prominent semitone intervals.

The following alto aria “Jesus ist ein guter Hirt” (Jesus is a shepherd true) shifts to a subjective, human perspective, but retains a dramatic minor tonality. Thanks to the distinct timbre and virtuosity of the violoncello piccolo part as the second upper voice, the setting gains considerable soloistic drive. Far from being a pastoral idyll, this movement depicts a rigorously tested yet faithful soul who draws personal courage from trusting in the redemption secured through Jesus’ sacrifice.

This yearning to enter more comforting pastures is fulfilled by the following B-flat major chorale verse with its gently lilting oboe and continuo trio. By employing the wellknown psalm paraphrase “Der Herr ist mein getreuer Hirt” (The Lord my faithful shepherd is), Bach’s unknown librettist integrated a hymn verse ideal for the Gospel message of the cantata. Here, the gentle dotted rhythms of the woodwind parts pave the way for the enchanting passing-note embellishments of the soprano part; at times, the setting’s light-footed movement and delightful breadth call to mind the galant-style organ trios with an obbligato wind instrument for which composers such as Bach student Johann Ludwig Krebs were well known.

The following accompagnato-recitative “Wann die Mietlinge schlafen” (If e’er the hirelings slumber) makes a vivid distinction between a shepherd born to a calling and one merely hired for money. From the very outset, the introductory section represents a tangible shift from shrouded stillness to active watchfulness, ere the tenor part increases in dramatic intensity with the growing threat.

Through its serene observations, the tenor aria is a sensitive rendering of what the redemptive presence of the Highest can inspire in the human soul. Here, the trinitarian-soft E-flat major tonality, swinging 9⁄8-metre and elegant unison string treatment engender a sense of unburdened refuge that may be considered a timeless apotheosis of selfless love – all without diminishing the magnitude of Jesus’ sacrifice.

The cantata closes with an unusually arioso- like four-part chorale setting of the fourth verse of the now lesser-known Ernst Christoph Homburg hymn “Ist Gott mein Schutz und Helfersmann” (With God my refuge, shepherd true). Although the setting returns to the cantata’s opening key of C minor, the expressive text radiates a confidence that culminates in the repeated closing phrase “Ich habe Gott zum Freunde” (For God is my companion): the hierarchical relationship between the saviour and humankind, as represented by the metaphorical shepherd and his flock, has given way to a conference of equals.

Libretto

1. Arie (Bass)

»Ich bin ein guter Hirt, ein guter Hirt läßt sein Leben für die Schafe.«

2. Arie (Alt)

Jesus ist ein guter Hirt,

denn er hat bereits sein Leben

für die Schafe hingegeben,

die ihm niemand rauben wird.

Jesus ist ein guter Hirt.

3. Choral

Der Herr ist mein getreuer Hirt,

dem ich mich ganz vertraue,

zur Weid er mich, sein Schäflein, führt

auf schöner, grünen Aue,

zum frischen Wasser leit er mich,

mein Seel zu laben kräftiglich

durchs selig Wort der Gnaden.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Wann die Mietlinge schlafen,

da wachet dieser Hirt bei seinen Schafen,

so daß ein jedes in gewünschter Ruh

die Trift und Weide kann genießen,

in welcher Lebensströme fließen.

Denn, sucht der Höllenwolf gleich einzudringen,

die Schafe zu verschlingen,

so hält ihm dieser Hirt doch seinen Rachen zu.

5. Arie (Tenor)

Seht, was die Liebe tut.

Mein Jesus hält in guter Hut

die Seinen feste eingeschlossen

und hat am Kreuzesstamm vergossen

für sie sein teures Blut.

6. Choral

Ist Gott mein Schutz und treuer Hirt,

kein Unglück mich berühren wird.

Weicht, alle meine Feinde,

die ihr mir stiftet Angst und Pein,

es wird zu eurem Schaden sein,

ich habe Gott zum Freunde.

Peter Wollny

“The Most Hidden Secrets of Harmony”

The cantata “Ich bin ein guter Hirt” (BWV 85) may not be one of Bach’s major works, but one can nevertheless recognise in it the sum of his creative work and his artistic striving.

15 April 1725, the Sunday of Misericordias Domini, on which the cantata “Ich bin ein guter Hirt” (BWV 85) was first performed in Leipzig’s Nikolaikirche, was – as far as we can tell from the surviving documents – probably not a particularly outstanding or remarkable day in Johann Sebastian Bach’s life. Bach had been in Leipzig for barely two years at this point. The family had settled into the somewhat cramped servants’ flat on several floors in the southern wing of the Thomasschule and had probably become somewhat accustomed to the hectic school routine. Bach’s young wife Anna Magdalena had given birth to three children in the three and a half years of their marriage – daughter Christiane Sophia Henrietta in March 1723, son Gottfried Heinrich in February 1724 and son Christian Gottlieb on 13 April 1725, who was baptised in St Thomas’ Church on 14 April, the day before the first performance of our cantata. With seven children and the unmarried sister of Bach’s first wife living with the family, it was getting crowded in the cantor’s flat at Thomaskirchhof. Bach himself had celebrated his 40th birthday a good three weeks earlier. He may have been thinking during these days that his next older brother Johann Jakob Bach had died in 1722 at exactly that age.

At the end of March 1725, Bach had somewhat prematurely completed his largest and artistically probably most ambitious project to date: the year of choral cantatas begun in June 1724. Behind him lay eight months of the most concentrated and extremely productive compositional activity – masterpieces every week. A few days after the performance of the last choral cantata for the time being, he then performed the fundamentally revised second version of his St John Passion of 1724 at the Good Friday Vespers in St Thomas’ Church, and again two days later, on Easter Sunday, he presented his newly created Easter Oratorio to the congregations of St Nicholas’ and St Thomas’ Churches. It is hard to imagine how Bach could muster the strength to create such great music week after week, rehearse it with his pupils and then perform it in public. I often wonder whether his family members, friends and colleagues and those around him were even aware of the tremendous artistic achievement Bach accomplished during this time, what unique masterpieces were created in their immediate vicinity.

Sovereign lightness of musical thought

Now one would like to assume that Bach took a calmer time after completing the choral cantata cycle, but far from it. As early as the second day of Easter, on 2 April 1725, he began a new series of cantatas, which are perhaps outwardly somewhat less conspicuous, but which are extraordinarily finely crafted and have a chamber-musical quality, as it were. So there is no question of physical or mental exhaustion, of the need to draw new strength and recreate the imagination. And anyone who has ever studied the autograph scores of these cantatas cannot help but be amazed at the certainty, even sovereign ease with which Bach put his musical thoughts down on paper. In view of the workload of the preceding months, there can hardly have been longer periods of reflection, tentative searching and cautious trial and error. Basically, the cantata “Ich bin ein guter Hirt” (I am a good shepherd) must have been begun on 8 April after the performance of the previous work and composed and rehearsed within a week – nota bene: a week in which the birth and baptism of one of his children also occurred.

In view of these briefly outlined biographical coordinates, there can be no doubt in my mind that Bach the man, whom his fellow world saw acting day in and day out, and Bach the artist, who filled the rastered paper with musical signs in his cramped composing room, had hardly anything to do with each other. To put it bluntly: Bach probably lived a completely normal life on the outside, like thousands of his contemporaries, and yet when he sat in his chamber, he communicated with the world spirit, so to speak. As informative and important as the ongoing exploration of Bach’s life and creative conditions may be, it does not really lead us to the actual roots of his creativity. Bach the artist remains an inaccessible, distant figure for us. It would probably be of no use to us at all if he had not been – as Paul Hindemith put it – of an “oyster-like secrecy” about his work, but as garrulous as a magpie. And if we had the opportunity to address Bach about his artistry and about the circumstances of his life, which are only hinted at here, I don’t think we would get a satisfactory answer. Bach would probably have shrugged his shoulders and muttered – as his biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel has handed down – “I have had to be industrious; anyone who is just as industrious will be able to get just as far.”

A profound approach to the texts

So, setting aside the biographical evidence as unproductive, when I look for an explanation of what makes Bach’s music so impressive and so special, I next look at the notes and visualise the compositional refinements. Indeed, the pure craftsmanship takes place at a level that one searches in vain for in many other composers. Even a piece as unpretentious at first as the opening dictum of the cantata “I am a good shepherd” is full of the wonders of double counterpoint. And the deeper we delve into the scores, the more clearly we realise that Bach’s handling of his texts is both refined and profound, that he has at his disposal an astonishing range of different possibilities for interpreting the text, and that he obviously thought through complex theological interpretations as well.

Depending on our educational background and inclinations, we can continue such investigations throughout our lives. And yet the magic of Bach’s music remains – untouched, as it were, by our attempts at intellectual empowerment – even after long and intensive study. Bach’s son Carl Philipp Emanuel seems to have recognised this when he wrote that his father’s works had “brought the most hidden secrets of harmony into the most artificial exercise” and that the melodies he invented were “strange, but always different, inventive, and not similar to any other composer”. No matter how one turns it around, there remains something mysterious and inexpressible in words. For the systematic, rhythmic, melodic and compositional exploration of the chosen thematic material revealed in almost every aria, every chorus and every figured chorale, to which Bach’s – as Forkel called it – “inventive and strange thoughts” take away the potential dryness of the polyphonic technique, aspires to nothing less than the discovery of musical perfection. Thus, a work such as the cantata “Ich bin ein guter Hirt” may not be one of Bach’s major works, but it nevertheless represents the sum of his creativity and artistic endeavour.

“Mysterious Sanskrit of Nature”

Let me return once more to the so enigmatic magic of Bach’s music, which is able to seize us so immediately but is so difficult to grasp intellectually. The Romantic poet and composer E. T. A. Hoffmann found an impressive poetic metaphor for this quality inherent in all truly great music: He perceived in the works of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven a voice that he called “the mysterious Sanskrit of nature spoken in tones”. We can take up this image and think further with its motifs: only a few people are able to speak and think in this “mysterious Sanskrit of nature”. They are the great artists, of whom only a few appear in each generation. But what they have to tell us in their immortal masterpieces can be understood (or at least guessed at) by all of us if we try to approach these works attentively, empathetically and humbly.

Here, of course, we are faced with a task that should not be underestimated. The understanding and love of music and art are obviously not part of the basic constitution of man. Rather, they are abilities that have to be awakened, fostered and learned, but which can also atrophy or not even be developed in the first place. It seems to me that it is particularly urgent to bear this in mind today, because we are undoubtedly living in an age in which technical progress has far outstripped spiritual progress. And the terrible images of the wanton destruction of millennia-old works of art, which until recently were proud testimonies to our civilisation, show us how fragile humanity’s cultural heritage really is. The words from the second great Faust monologue – “What you have inherited from your fathers, acquire it in order to possess it” – can therefore be understood as a warning of almost oppressive topicality.

For us, this means that Bach’s works need to be permanently cultivated, researched and passed on to future generations, so that they can continue to have an effect and give their listeners edification, joy and instruction, even knowledge.

The writer Hans Wollschläger, whom I hold in high esteem, once formulated the idea that music always says more than we can know about it and the world. Therefore, one can and should always strive to know more about it than one can say. In this spirit, I wish you a fruitful second listening to the cantata.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).