Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ

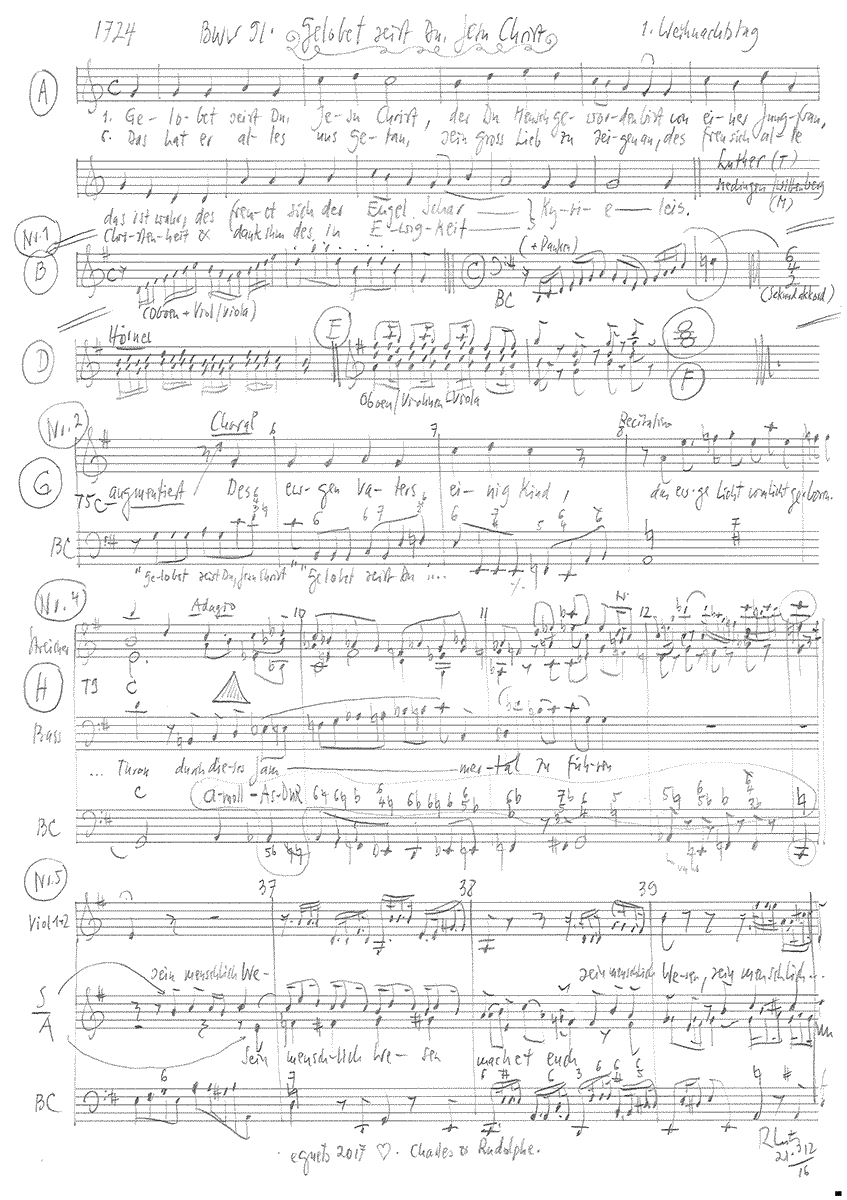

BWV 091 // For Christmas Day

(All glory to thee, Jesus Christ) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn I+II, timpani, oboe I–III, strings and basso continuo

First performed on 25 December in 1725, cantata BWV 91 “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ” (All glory to thee, Jesus Christ) is a glorious Christmas composition befitting Bach’s chorale cantata cycle. Despite the considerable size and power of the two outside tutti choruses, the cantata is a highly efficient composition whose strikingly earnest tone in light of the joyful feast day speaks volumes about how Christmas was perceived in Bach’s time.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Julia Schiwowa, Susanne Seitter, Alexa Vogel, Maria Weber, Mirjam Wernli Berli

Alto

Jan Börner, Francisca Näf, Antonia Frey, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Sören Richter, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Eva Borhi, Petra Melicharek

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone, Katya Polin

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Ingo Müller, Ann Cathrin Collin

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Corno

Olivier Picon, Thomas Müller

Timpani

Martin Homann

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Dirk Börner

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Ludwig Stocker

Recording & editing

Recording date

23.12.2016

Recording location

St. Gallen (Schweiz) // Kirche St. Mangen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

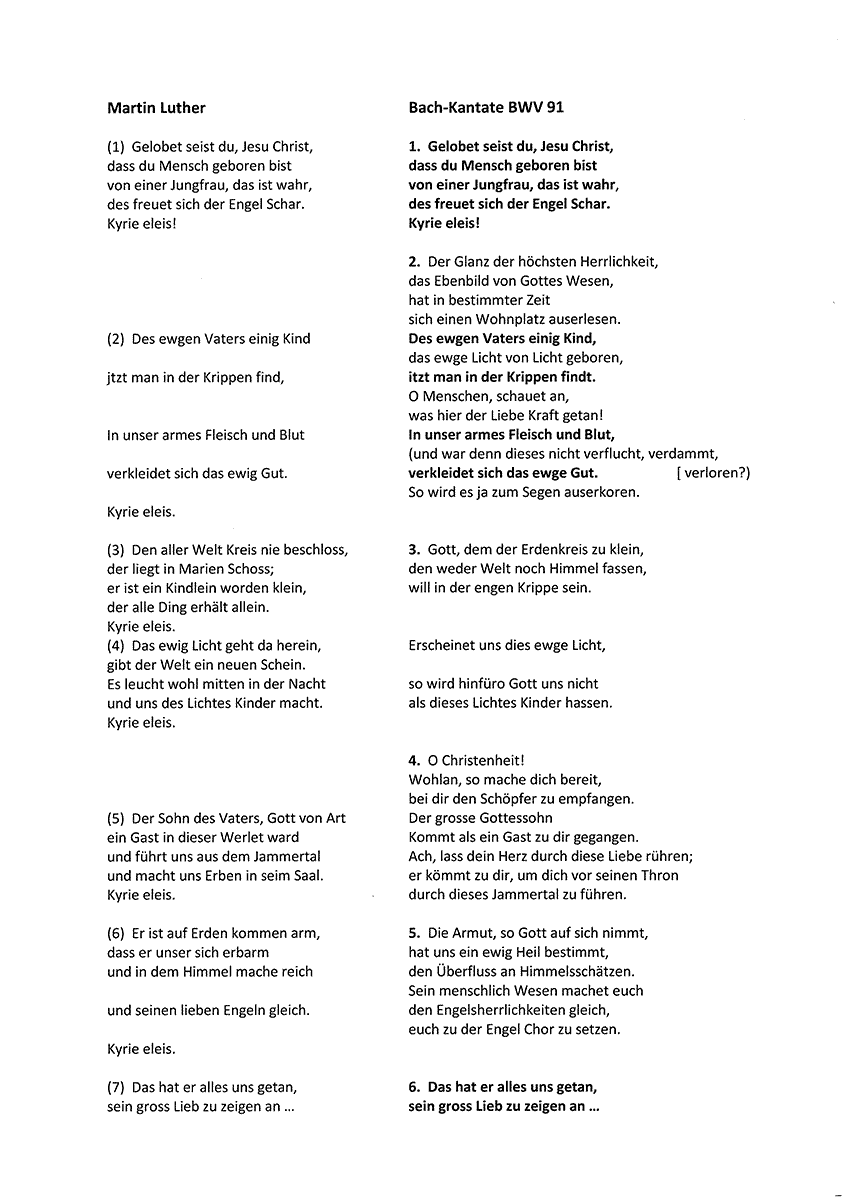

Text No. 1, 6

Martin Luther (1524)

Text No. 2–5

Arranger unknown

First performance

First Day of Christmas,

25 December 1724

In-depth analysis

The richly orchestrated introductory chorus opens with a combination of long notes by the horns and festive ascending lines by the strings and oboes, ere the whole orchestra erupts in fragmented fanfare motives. Although this moment of unbridled power would also suit a resurrection setting, here it declaims the human incarnation of Christ as an event of radical significance. In this orchestral setting, which circles around the shifting tonal centres with military-style might, the text of the hymn is woven in line for line by the vocal parts, whose dynamic coloraturas unwind only in the dance-like syncopated figure of the “Kyrie eleis” – closing words that are drawn out like a promise.

Set in E minor, the soprano recitative is replete with wonder at the miracle of the advent of Christ. As if Luther’s familiar hymn alone could describe this event in words, the second chorale verse is interpolated into the festive recitative, thus also lending the arioso continuo part, with its modulating pre-imitations, a motivic import.

The tenor aria, through the addition of three oboes, distinctly belongs to the pastoral world. In a measured triple metre with gentle dotted rhythms, the A minor setting embodies the contradiction between the lowly manger and universe-spanning majesty; here, the tenor soloist, seemingly trapped in his earthly existence, is illuminated in the middle section by the “eternal light” on high.

Accompanied by a splendid string timbre, the bass recitative meditates on the consequences of Christ’s birth for the individual. By imploring humans to welcome the creator as a guest in their hearts, the message of Christmas is both personalised and reaffirmed. Against the backdrop of this immeasurable hope, the “vale of tears” that must be overcome on the path to God’s throne is expressed in an ascending figure across the full baritone range, whose jarring chromaticism is unusually drastic, even for Bach. Following the suspended cadence, the violins and continuo drift a full four octaves apart – the chasm between the heavenly and earthly sphere could hardly be rendered more vividly.

Overcoming this gulf demands a collective effort, which is provided in the ensuing duet by a unison string part (over a walking bass line) whose incessant dotted rhythms and terse cadences evoke a merciless state of agitation. The soprano and alto voices, by contrast, open with imitative lines that evolve into a heartfelt duo in which the notion of voluntary poverty and the inevitable suffering of Christ compassionately takes shape. Contrary to the opinion of some commentators, it was not Bach’s aim here to set the opposing key words as a musical contrast, but to make clear that the two concepts go hand in hand: “poverty” is a precondition of “heaven’s treasures”, and only when we accept Christ as a suffering human can we hope for the angels’ liberated song of majesty. Accordingly, the words “mortal nature” in the middle section are underscored by a figure replete with sighs, calling to mind the “vale of tears” from the bass recitative. For Bach, it apparently remains part of the conditio humana to seek the light through suffering and many sorrows – that Christ took this burden upon himself is what constitutes the wonder of Christmas.

In the closing chorale, a movement based on both the text and mediaeval melody of Luther’s hymn, Bach opts for a grand setting complete with enraptured flourishes by the horns. In this gesture of defiant joy, the hard-won trust in God’s act of love – as manifested by Christ in the manger – is brought to expression. Nothing is lost, everything begins with this child: Kyrie eleison!

Libretto

1. Chor

Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ,

daß du Mensch geboren bist,

von einer Jungfrau, das ist wahr,

des freuet sich der Engel Schar.

Kyrie eleis!

2. Rezitativ und Choral (Sopran)

Der Glanz der höchsten Herrlichkeit,

das Ebenbild von Gottes Wesen,

hat in bestimmter Zeit

sich einen Wohnplatz auserlesen.

Des ewgen Vaters einigs Kind,

das ewge Licht von Licht geboren,

itzt man in der Krippe findt.

O Menschen, schauet an,

was hier der Liebe Kraft getan!

In unser armes Fleisch und Blut,

(und war denn dieses nicht verflucht, verdammt, verloren?)

verkleidet sich das ewge Gut,

so wird es ja zum Segen auserkoren.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Gott, dem der Erden Kreis zu klein,

den weder Welt noch Himmel fassen,

will in der engen Krippe sein.

Erscheinet uns dies ewge Licht,

so wird hinfüro Gott uns nicht

als dieses Lichtes Kinder hassen.

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

O Christenheit!

Wohlan, so mache dich bereit,

bei dir den Schöpfer zu empfangen.

Der große Gottessohn

kömmt als ein Gast zu dir gegangen.

Ach, laß dein Herz durch diese Liebe rühren;

er kömmt zu dir, um dich vor seinen Thron

durch dieses Jammertal zu führen.

5. Arie (Duett Sopran, Alt)

Die Armut, so Gott auf sich nimmt,

hat uns ein ewig Heil bestimmt,

den Überfluß an Himmelsschätzen.

Sein menschlich Wesen machet euch

den Engelsherrlichkeiten gleich,

euch zu der Engel Chor zu setzen.

6. Choral

Das hat er alles uns getan,

sein groß Lieb zu zeigen an;

des freu sich alle Christenheit

und dank ihm des in Ewigkeit.

Kyrie eleis!

Ludwig Stocker

Presence of the Absent

On painting and sculpture and their approach to the text of the Christmas cantata “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ” (BWV 91)

The themes for my painting and sculpture are almost self-evident. They are related to the feast we celebrate today with Bach’s Christmas cantata and liturgically in the coming days.

The picture refers to the Annunciation to Mary, the sculpture to the Incarnation, to Jesus’ birth and Christmas. The Incarnation is a mysterious event. The art historian and philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman said:

“The Incarnation of Christ is the darkest of mysteries, but one that calls for figuration because it is about the visible existence of the divine in the person of Jesus Christ.”

The Annunciation of the Angel to Mary is perhaps an even darker mystery, powerful in its narrative form, almost mythical in character. There are a great many depictions of the Annunciation in art history; they reflect the piety and beliefs of their time.

There are even more depictions of the Nativity, that is, of Christmas, from great artists such as Giotto, Konrad Witz, Ghirlandaio, Tintoretto… to the countless forms of naïve nativity scenes as an expression of popular piety.

Tonight’s concert brings to our attention that the performance of Bach’s cantatas today are largely no longer embedded in the original context of the liturgy. The performance of the cantata, borne of deep faith, although taking place in the sacred space, has become a largely secular concert event. Nevertheless, Bach’s composition holds its own even in the changed environment – and, in my opinion, primarily because of its high artistic quality.

My painting and the sculpture are also no longer permanent church installations for deepening meditation, prayer and piety. They will be cleared away again after the feast days. The sculpture is not made of stone, but of the fragile, weightless, ephemeral material polystyrene. In this way, the mysteriously spiritual, the Annunciation and Incarnation, are represented in ephemeral, quite mundane materials.

How can I still depict the ultimately unfigurable mystery of the Annunciation and the Incarnation today? How can I depict the Annunciation scene, which no human being has seen and which is completely left to our imagination and faith, and how can I depict the angel, the immaterial?

How can contemporary forms be found that make religious themes comprehensible even to the enlightened, critical contemporary who may even be agnostic or atheist? Where biblical texts are no longer understood by enlightened contemporaries and faith is disappearing more and more, music, painting and sculpture, which originally had reference to religion, increasingly touch on a purely aesthetic and leisurely level.

Is the role of form addressed here? I think so. Because form and colour speak for themselves. The autonomy of the work of art, its detachment from the literary, from narrative themes, is a requirement that has been expanded and thematised in modernism – and rightly so. But hasn’t the effect of pure form on the experience of a work of art always been an unconscious fact?

Here are two examples: An ancient Egyptian statue of a king or god has a strong effect on the viewer, even if he knows nothing about its message or its meaning. A cantata by Bach undoubtedly has a great effect on the listener, even if he no longer understands the underlying text and or does not want to understand it. Even purely instrumental works that manage without words in their profundity, such as the Goldberg Variations or Chaconne for solo violin (BWV 1004), move us in our innermost being. The effect of a work of art is certainly based to a considerable extent on its formal structure.

A thought experiment: What effect would our Bach cantata have on the listener if the vocal parts were replaced by solo instruments? Or: What would be the effect of my painting if the figurative parts in it were replaced by purely abstract blobs of colour, i.e. detached from text and figuration? Probably the effect would be quite different. So it is not quite the case that parts of the content of a composition can simply be dispensed with.

Let us deal objectively and concretely with the task I have set myself. At the beginning, there is an indefinable flow through the head or through other unconscious zones: Thoughts and feelings that sometimes flow in at night, also create restlessness, fears, and yet are finally grasped again, in the knowledge of the connections, the presentness, simultaneity of everything.

So it is about a Bach cantata for Christmas and I intend to make a picture and a sculpture to go with it.

Reflections on the picture – renunciation of aureoles, a condition for allowing inter-humanity to emerge

My starting point for the cantata was the chorale verse with the text by Martin Luther in the opening chorus: “Praised be you, Jesus Christ, / that you were born a human being, / of a virgin, that is true, / (…)”.

So it was a matter of remembering an event in salvation history. And I wanted to link up with representations of religious content in a time when memory was forgotten, to a time when art was not primarily art but an expression of faithful worship.

A deep faith characterised medieval art until the middle of the 15th century. Then a break occurred. This change can be impressively illustrated by two so-called art treatises, which were written only about 50 years apart. The first was written by Cennini around 1390.

It reflects the conception of art in 14th century painting. Cennini opened his Libro dell’ Arte with an invocation to God, the Virgin Mary and the saints.

In contrast, Leon Battista Alberti, 50 years later, as an important art theorist of his time, introduced his writing on painting in 1435 with a homage to the mathematicians and demanded autonomy for the painter’s point of view. Piero della Francesca’s depiction of the Annunciation – created around 1470 in Perugia in a time of upheaval, of incipient secularisation, the most violent phase of which we are still in today – falls into this period.

Out of the feeling of also being in a time of great upheaval, I have quoted the heads of Angel and Mary from Piero’s picture in my painting. The aureoles that still hover over the heads of the angel and Mary in Piero’s painting have been removed, however. The scene thus becomes an interpersonal encounter, a dialogue, it is secularised. To quote in my painting means to take over a fragment from an old painting, because it speaks to a latent side of me, as if it were my own. In recognising something that has already been imprinted, I recognise myself. Simultaneity arises.

So I can answer the question that may arise: Did you make these heads yourself with yes and no. With yes, because I made them in the realm of my own. Yes, because I found and assimilated them in the realm of my image-afflictions. They became my heads. No, because they were made by a Xerox machine, exactly according to my instructions, as they are now in this picture.

Angel and Mary are suspended in a new context. Pushed into the picture by a striking insertion of pure colour (red, yellow, green) and light white, the faces assert themselves in an otherwise rather chaotic environment and are thus brought back into the realm of the inexplicable.

The figurations, taken from the 15th century, are traces of a cultural past. They are, in the words of philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, “a ‘remainder’ or a ‘relic’, detached from the religious edifice, yet they contain a demand that cannot be said goodbye to”.

Reflections on sculpture – the divestment of the divine as a prerequisite for devotion

The soprano recitative in the cantata inspired me to sculpt. The beginning of the text reads: “The radiance of the highest glory, / the image of God’s being, / has in certain time / chosen a dwelling place for itself.”

Two movements can be seen in the sculpture. On the one hand, the parallel vertical line pointing upwards into infinity. On the other, the unsettling, slightly sloping horizontal. Thorns or antennae protrude from it. The interpretation is left to the viewer. Above this horizontal plate we see a figuration in a stooped posture. It is the posture of a turning towards and is based on the idea of kenosis. The Greek kenosis means that Jesus, in turning to us, in becoming human, laid down his divinity, literally emptied himself of it.

The sculpture is made up of moving plate-like forms. This creates a volume with empty spaces. The figure opens up on all sides, including into the interior. We know to whom this promising opening points. It points to the incarnation of Jesus, which Bach sang about in this wonderful cantata.

In conclusion: the longing to penetrate into heaven

I see my painting of the Annunciation and my sculpture of the Kenosis as a unity of the mystery of Christmas. Picture and sculpture thematise the presence of the absent.

I have chosen two different ways of creating it. On the one hand, there is the picture. The Annunciation is a two-dimensional design. You cannot touch a picture, just as the angel did not touch Mary at the Annunciation. The mystery is incomprehensible. On the other hand, there is the three-dimensional sculpture, the Incarnation. A sculpture can be touched, it is haptic, the Incarnation in this world.

What has remained of the Annunciation and Incarnation for us who were born later? For the believer, perhaps the sentence that is so difficult to understand: “Take and eat, this is my body”. Even in the age of genetic manipulation – of the cosmos explored in great depths – of enlightenment – of God declared dead, the longing to reach heaven has remained with us. A long tradition of artistic representations of the Annunciation and Christmas tell of this longing; they have remained the central gateway to this mystery for many of us today. Above all, Bach’s Christmas music.

Literature

– Georges Didi-Huberman, Fra Angelico Dissimilarity and Figuration, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 1995

– Jean-Luc Nancy, Deconstructing Christianity, Diaphanes Verlag, Berlin 2008

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).