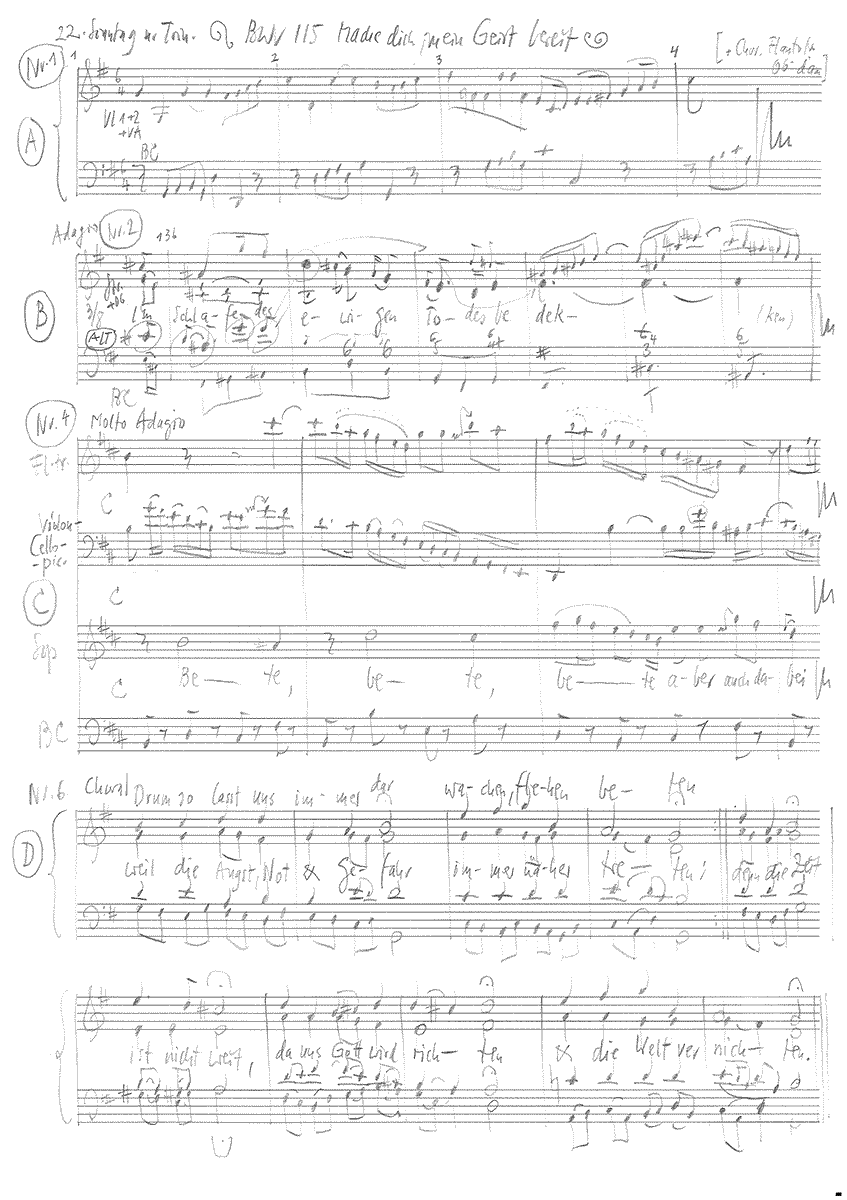

Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit

BWV 115 // For the Twenty-second Sunday after Trinity

(Get thyself, my soul, prepared) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute, oboe d’amore, horn, violoncello piccolo, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Olivia Fündeling, Anna Walker

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Katharina Jud, Misa Jäggin, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Achim Glatz, Raphael Höhn, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Oliver Rudin, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó, Christoph Rudolf

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone, Katya Polin

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violoncello piccolo

Balázs Máté

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe d’amore

Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Dana Karmon

Transverse flute

Marc Hantaï

Corno

Olivier Picon

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Jörg Andreas Bötticher

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Markus Wild

Recording & editing

Recording date

20.10.2016

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 6 and beginning of No. 4

Johann Burchard Freystein, 1695

Text No. 2–5

Arranger unknown

First performance

Twenty-second Sunday after Trinity,

5 November 1724

In-depth analysis

The chorale cantata “Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit” (Get thyself, my soul, prepared) BWV 115 was composed for the 22nd Sunday after Trinity in 1724 and thus forms part of Bach’s second Leipzig cantata cycle. Surviving transcripts and partial copies of the work from after 1800 indicate that August Eberhard Müller (Thomascantor from 1800/04 until 1810) continued to use the cantatas in church music, a decision motivated in equal parts by practicality and respect. It should be noted, however, that these performances are not an early form of a “Bach renaissance” but rather represent a swansong in baroque church-music practice.

The introductory chorus opens with a twovoice continuo part and unison strings, whose admonitory figure of repeated notes and erratically circling gestures serve to caution humankind against the unforeseen “evil day” of judgement. Although the unexpected entry of the woodwinds, transverse flute and oboe d’amore somewhat brightens the timbre of this gruff, stringent music, it does little to soften its motivic rigour. Amid this setting – hampered as it seems by a theological handbrake – the choir, supported by horns, enters with the first chorale line, whose block-like presentation nonetheless features some fine timbral effects, such as on the words “Bete” (pray) and “Versuchung” (temptation). Within the confines of this efficiently constructed movement, Bach also skilfully distinguishes certain passages in the orchestral writing. For instance, at the transition to the final chorale line, the unison string passage appears as a lifeline tossed dramatically to save the choristers from the treacherous swamp of a heedless life.

This gesture of warning is taken up again in the alto aria, in which neither the soothing 3/8 - metre nor the warm timbre of the oboe d’amore can mask the underlying gravitas of the music, which echoes the bittersweet tone of a Passion setting. Here, the endangered soul must be woken from the sinful slumber so temptingly portrayed by the rocking quaver line – what the loving calls of the alto fail to do, the threats of the allegro middle section, whipped on by cracking lightning, are quite able to manage. Indeed, it is audibly clear that no human can escape God’s triumphant justice, and thus sleep as a symbol of eternal death can – despite the lulling tones of the music – no longer be seen as a source of consolation.

This punishment, while deferred for now, hangs like the sword of Damocles over the following bass recitative. Although the setting speaks of God as the loyal watchman of the soul, his disappointment in a world debauched by Satan pervades almost every bar. The movement portrays more a resigned King Lear than a dazzling Lord on High who castigates the “false brothers”.

In keeping with this theme, the soprano aria, a poignant molto adagio setting, projects a funereal tone from the very first note. In an expressive duo of transverse flute and violoncello piccolo, a fragile, enticing soundscape emerges with a barely audible continuo line of inimitable subtlety. Bach’s true object, however, is first revealed with entry of the soloist, who speaks of prayer as the fundamental expression of the human condition – the music is radical in its very stillness and transforms the sincere pleas of the vocalist into a provocative chastisement of a loud and egotistical world. Why precisely this heartfelt simplicity can serve as a path to mercy and new strength is explained in the following tenor recitative: God opens his ears when we call to him with sincerity, which is also why he selflessly gave the world his only son, whose vital help is portrayed in the arioso closing phrase as encouragement that accompanies humankind every step of the way.

The closing chorale, a verse from Johann Burchard Freystein’s hymn of warning, thus serves to decisively fortify the reformed congregation of singers. With its unadorned progression and culmination in a glaring major chord, the setting mirrors the eschatological gravitas of Freystein’s theologising verse, which is not only resigned to the impending destruction of the world, but even emphatically welcomes it.

Libretto

1. Choral

Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit,

wache, fleh und bete,

daß dich nicht die böse Zeit

unverhofft betrete;

denn es ist

Satans List

über viele Frommen

zur Versuchung kommen.

2. Arie (Alt)

Ach schläfrige Seele, wie? ruhest du noch?

Ermuntre dich doch!

Es möchte die Strafe dich plötzlich erwecken

und, wo du nicht wachest,

im Schlafe des ewigen Todes bedecken.

3. Rezitativ (Bass)

Gott, so vor deine Seele wacht,

hat Abscheu an der Sünden Nacht;

Er sendet dir sein Gnadenlicht

und will vor diese Gaben,

die er so reichlich dir verspricht,

nur offne Geistesaugen haben.

Des Satans List ist ohne Grund,

die Sünder zu bestricken;

brichst du nun selbst den Gnadenbund,

wirst du die Hilfe nie erblicken.

Die ganze Welt und ihre Glieder

sind nichts als falsche Brüder;

doch macht dein Fleisch und Blut hiebei

sich lauter Schmeichelei.

4. Arie (Sopran)

Bete aber auch dabei

mitten in dem Wachen!

Bitte bei der großen Schuld

deinen Richter um Geduld,

soll er dich von Sünden frei

und gereinigt machen!

5. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Er sehnet sich nach unserm Schreien,

er neigt sein gnädig Ohr hierauf;

wenn Feinde sich auf unsern Schaden freuen,

so siegen wir in seiner Kraft:

indem sein Sohn, in dem wir beten,

uns Mut und Kräfte schafft

und will als Helfer zu uns treten.

6. Choral

Drum so laßt uns immerdar

wachen, flehen, beten,

weil die Angst, Not und Gefahr

immer näher treten;

denn die Zeit

ist nicht weit,

da uns Gott wird richten

und die Welt vernichten.