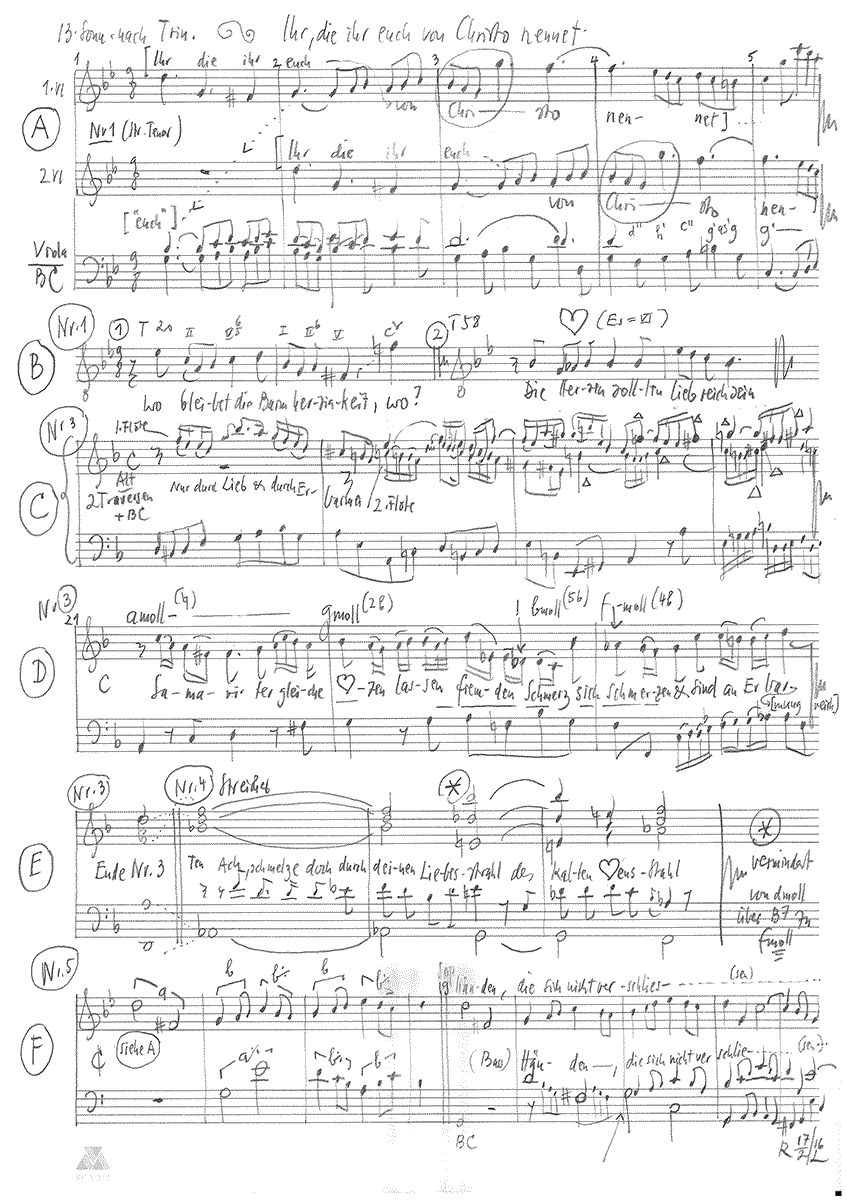

Ihr, die ihr euch von Christo nennet

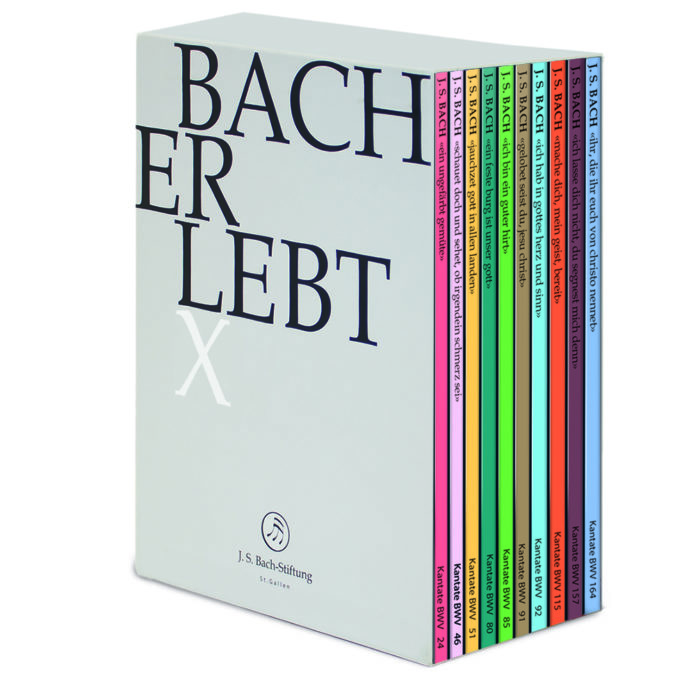

BWV 164 // For the Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity

(You who the name of Christ have taken) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, transverse flute I+II, oboe I+II, strings und basso continuo

Cantata BWV 164 was first performed in Leipzig on the 13th Sunday after Trinity in 1725. Nevertheless, the work could easily be mistaken as a latecomer to Bach’s Weimar cantata oeuvre: the libretto is by Salomo Franck, there is no introductory chorus, and the flowing cantabile music is exquisitely orchestrated in chamber-music fashion.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Dana Karmon

Transverse flute

Claire Genewein, Yoko Tsuruta

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Karen Horn

Recording & editing

Recording date

19.02.2016

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–5

Salomo Franck, 1715

Text No. 6

Elisabeth Cruciger, 1524

First performance

Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity,

26 August 1725

In-depth analysis

The introductory aria, in particular, with its tightly knit consort and quaint style, seems to be composed more with the intimate audience of a courtly gathering in mind than the imposing, resonant acoustics of Leipzig’s city churches. In this movement, the gently flowing 9⁄8 metre stands in stark contrast to the dramatic G minor tonality and accusatory libretto that addresses the discrepancy between Christian duty and actual practice; the dotted crotchets of the head motive stab precisely like the admonitory finger of a forbidding preacher or a prophet painted on a church wall. In the B section, Bach illustrates the “kindness” of mercy in an Elysian string episode before reintroducing the instrumental head motive to confront the virtue of Christ’s example with the “stony hardness” of the human heart. In this cathartic moment, Bach demonstrates great artistic interpretation by – in keeping with Franck’s libretto – leaving the last word, at least for now, with the harsh judgement of a world pervaded by egotism.

The bass recitative, set as a dialogic sermon of penance, is no less severe in tone. Through the contrast of an arioso passage on the message of love from the Sermon on the Mount and a prosaic depiction of the egotism of everyday life, human behaviour is revealed to be nothing short of a constant transgression of the divine command. Indeed, the prominent placing of “priest and Levite” as a particularly repugnant example of the callous zeitgeist makes abundantly clear that in Weimar and Leipzig, too, the fish rots from the head.

In the face of such futile remonstrations, it appears that only a complete change of tack can help. For this, Bach sets a trio in close imitation that is soothingly softened by the dulcet tones of the transverse flutes and thus expresses caring love – regardless of how tough the demand to show mercy may appear, this yoke is audibly light. At the beginning of the second section of the aria, Bach reveals the meaning of such loving devotion to the downtrodden and needy in a descending, musical gesture of aide. That this attitude of “Hearts Samaritan in kindness” is anything other than natural, however, is equally evident in the unique and otherworldly timbre of the flutes.

The soothing power of God’s radiant love is underscored in the following recitative through the addition of a string accompaniment. In this moment of demonstrative repentance, declaimed appropriately by a heroic tenor, Bach seems to employ the full gamut of baroque ornamentation, as defined by masters such as Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel, Kapellmeister in Gotha, in his treatise on the recitative (Abhandlung vom Recitativ).

In the following duet, Bach puts into practice a veritable compendium of baroque musical theology. The unity achieved among humans and with God through a life of compassion is summarised in a rich, unison passage in which violins, oboes and transverse flutes hold equal sway. And as a duet for soprano and bass, the setting is plausible also from the perspective of scenic realism: it takes two to give and receive. Nevertheless, it remains audibly difficult for the notoriously imperceptive humans to grasp the transformation of the head motive, which now soars heavenwards in both the continuo and the upper orchestral parts. The fact that God gives to those who follow the example of his boundless love is illustrated here in music that seems extraordinarily inspired by Franck’s morally charged metaphors – from the sympathetically weeping eye, to the loving heart, to the helping hand.

The cantata ends with a chorale, a vehicle that Bach evidently appreciated to summarise and conclude complex libretti. Here, Elisabeth Cruciger’s moving appeal to weaken the “former man” in order that the “new” may live in the spirit of God is particularly fitting: to appreciate the life of Christ means to see and discover him “here on earth now” first and foremost in our neighbour’s need.

Libretto

1. Arie (Tenor)

Ihr, die ihr euch von Christo nennet,

wo bleibet die Barmherzigkeit,

daran man Christi Glieder kennet?

Sie ist von euch, ach, allzu weit.

Die Herzen sollten liebreich sein,

so sind sie härter als ein Stein.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Wir hören zwar, was selbst die Liebe spricht:

Die mit Barmherzigkeit den Nächsten hier umfangen,

die sollen vor Gericht

Barmherzigkeit erlangen.

Jedoch, wir achten solches nicht!

Wir hören noch des Nächsten Seufzer an!

Er klopft an unser Herz; doch wirds nicht aufgetan!

Wir sehen zwar sein Händeringen,

sein Auge, das von Tränen fleußt;

doch läßt das Herz sich nicht zur Liebe zwingen.

Der Priester und Levit,

der hier zur Seite tritt,

sind ja ein Bild liebloser Christen;

sie tun, als wenn sie nichts von fremdem Elend wüßten,

sie gießen weder Öl noch Wein

ins Nächsten Wunden ein.

3. Arie (Alt)

Nur durch Lieb und durch Erbarmen

werden wir Gott selber gleich.

Samaritergleiche Herzen

lassen fremden Schmerz sich schmerzen

und sind an Erbarmung reich.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Ach! schmelze doch durch deinen Liebesstrahl

des kalten Herzens Stahl,

daß ich die wahre Christenliebe,

mein Heiland, täglich übe,

daß meines Nächsten Wehe,

er sei auch, wer er ist,

Freund oder Feind, Heid oder Christ,

mir als mein eignes Leid zu Herzen allzeit gehe!

Mein Herz sei liebreich, sanft und mild,

so wird in mir verklärt dein Ebenbild.

5. Arie (Duett Sopran, Bass)

Händen, die sich nicht verschließen,

wird der Himmel aufgetan.

Augen, die mitleidend fließen,

sieht der Heiland gnädig an.

Herzen, die nach Liebe streben,

will Gott selbst sein Herze geben.

6. Choral

Ertöt uns durch dein Güte,

erweck uns durch dein Gnad!

Den alten Menschen kränke,

daß der neu leben mag

wohl hier auf dieser Erden,

den Sinn und all Begehrden

und Gdanken habn zu dir.