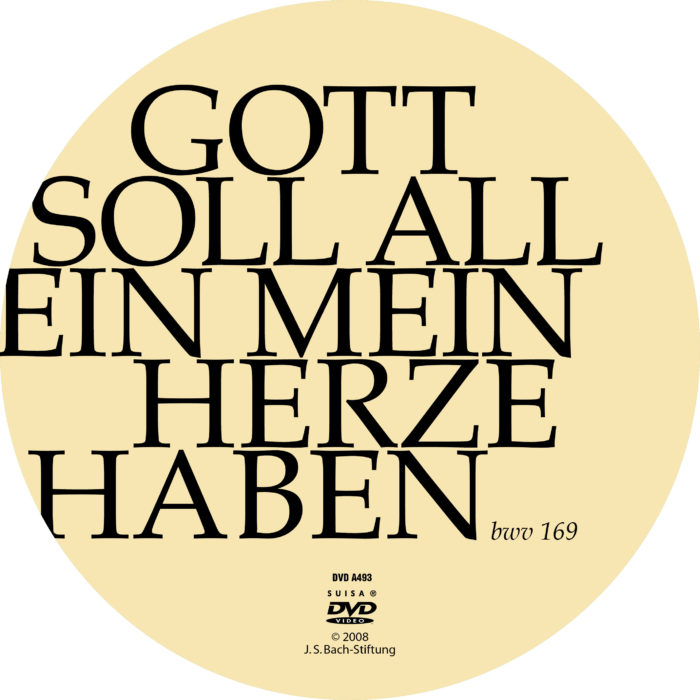

Gott soll allein mein Herze haben

BWV 169 // For the Eighteenth Sunday after Trinity

(God all alone my heart shall master) for alto, vocal ensemble (chorale), oboe I+II, taille, strings and continuo.

Like many church works of Bach’s 1726/27 cycle, cantata BWV 169 was conceived as a solo cantata (with a four-voice closing chorale), suggesting both a shift in Bach’s compositional focus and the availability of capable soloists in the chorus musicus of that school year.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Soloists

Alto

Claude Eichenberger

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei

Tenor

Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Martin Stadler, Luise Baumgartl

Oboe da caccia

Dominik Melicharek

Taille

Dominik Melicharek

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Theorbo

Juan Sebastian Lima

Organ

Rudolf Lutz

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Christian Lucas Hart Nibbrig

Recording & editing

Recording date

09/19/2008

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–6

Christoph Birkmann

Text No. 7

Martin Luther, 1524

First performance

Eighth Sunday after Trinity,

20 October 1726

In-depth analysis

The work opens with an extended sinfonia, making for a formal introductory movement that compensates well for the reduced number of vocalists. For this setting, Bach revises an earlier concerto movement for an unknown solo instrument; a reworking which together with the fifth movement of this cantata, found its way at the end of the 1730s into the E Major Concerto for Harpsichord and Orchestra (BWV 1053). The solo part, assigned to the organ in the cantata, appears to have been played directly from the score, indicating that Bach – a virtuoso organist – may well have played the part himself.

Following the expansive introductory movement, the arioso commences with an extended continuo ritornello that provides a relaxed framework for the cantabile motto “God all alone my heart shall master”, a head motive that is interspersed with figurative recitatives. In aria no. 3 the librettist and composer embark on a risky venture, beginning as they do with the already oft-recurring motto. In the new musical setting, however, Bach combines a striding bass with a nervous, almost jazzlike syncopated organ part that stands in stark juxtaposition to the hymn-like quality of the vocal lines. Compared to the highly contrasting soliloquy of the preceding arioso, this aria seems to exude open acceptance of the biblical word as the foundation of life’s truth.

Despite its brevity, the alto recitative no. 4 proves to be a rich collage of images and attributes expressing God’s love and its import for human existence. Here, the text is rich in allusion to the wonder of the Passion, referring to both the bosom of Abraham and Elijah’s chariot. The following aria “Die in me, world!” resumes this sentiment with a mesmerising siciliano form and the “have mercy!” tonality of B minor. In this movement, the intensity of the interplay between the various parts stands in such bold contrast to the libretto’s plain condemnation of worldly desires that it would not be entirely surprising to learn the music stemmed from an earlier source. Either way, the later reworking of this movement as the middle section of the Harpsichord Concerto in E Major is a potent reminder of the great effort and sensitivity with which Bach approached his parody compositions.

The following recitative abruptly draws our attention from the quixotic reflections of “religious specialists” to the earthly necessity of loving one another in the here and now. Here, the text’s somewhat dry reference to Christ’s directive exposes a weakness of Lutheran ethic: where do we find the motivation to love our neighbour if deeds of compassion are no longer necessary for salvation? The closing chorale provides a moving answer to this dilemma by singing in vibrant A major of the fervent “tenderness” that is inherent to a life of fellowship and goodness of heart. In this setting, Bach musically transforms the concept of virtue into an experience of the senses, while its identity as a Kyrie lends both choral movement and text liturgical import.

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Arioso & Rezitativ

Gott soll allein mein Herze haben.

Zwar merk ich an der Welt,

die ihren Kot unschätzbar hält,

weil sie so freundlich mit mir tut,

sie wollte gern allein

das Liebste meiner Seele sein;

doch nein: Gott soll allein mein Herze haben,

ich find in ihm das höchste Gut.

Wir sehen zwar

auf Erden hier und dar

ein Bächlein der Zufriedenheit,

das von des Höchsten Güte quillet:

Gott aber ist der Quell, mit Strömen angefüllet,

da schöpf ich, was mich allezeit

kann sattsam und wahrhaftig laben.

Gott soll allein mein Herze haben.

3. Arie

Gott soll allein mein Herze haben,

ich find in ihm das höchste Gut.

Er liebt mich in der bösen Zeit

und will mich in der Seligkeit

mit Gütern seines Hauses laben.

4. Rezitativ

Was ist die Liebe Gottes?

Des Geistes Ruh,

der Sinnen Lustgeniess,

der Seele paradies,

sie schliesst die Hölle zu,

den Himmel aber auf;

sie ist Elias Wagen,

da werden wir in Himmel nauf

in Abrahms Schoss getragen.

5. Arie

Stirb in mir,

Welt und alle deine Liebe,

dass die Brust

sich auf Erden für und für

in der Liebe Gottes übe,

stirb in mir,

Hoffart, Reichtum, Augenlust,

ihr verworfnen Fleischestriebe!

6. Rezitativ

Doch meint es auch dabei

mit eurem Nächsten treu;

denn so steht in der Schrift geschrieben:

Du sollst Gott und den Nächsten lieben.

7. Choral

Du süsse Liebe, schenk uns deine Gunst,

lass uns empfinden der Liebe Brunst,

dass wir uns von Herzen einander lieben

und in Friede auf einem Sinn bleiben.

Kyrie eleis.