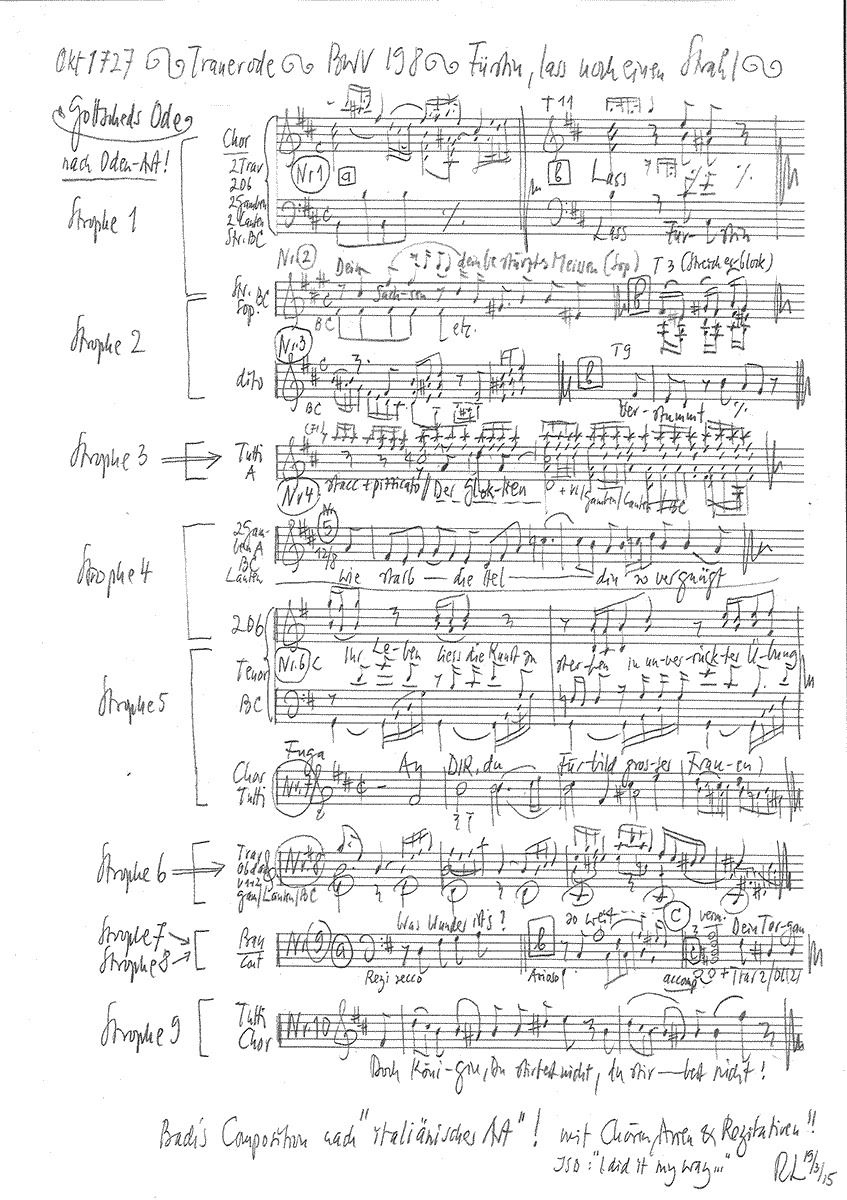

Laß, Fürstin, laß noch einen Strahl

BWV 198 // Funeral music

(Let, Princess, let still one more glance) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute I+II, oboe d’amore I+II, viola da gamba I+II, liuto I+II, strings and basso continuo

The performance of the funeral ode “Let, Princess, let still one more glance” BWV 198 on 18 October 1727 in Leipzig’s university church, the “Paulinerkirche”, numbers among the most prominent social successes of Bach’s career. As noted in a newspaper of the time, the event was distinguished by “the attendance of princely and comital personages, high ministers, cavaliers and other foreigners … in addition to a great number of elegant ladies”, who had come to pay their respects to queen Christiane Eberhardine, who had died on 4 September.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Olivia Fündeling, Guro Hjemli, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Maria Weber

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Liliana Lafranchi, Damaris Rickhaus, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel, Jonathan Spicher

Bass

Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Oliver Rudin, Will Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Dorothee Mühleisen, Claire Foltzer, Sabine Hochstrasser, Yuko Ishikawa, Anita Zeller

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Zimmermann, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Dominik Melicharek, Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Transverse flute

Claire Genewein, Renate Sudhaus

Viola da gamba

Paolo Pandolfo, Amélie Chemin

Lute

Maria Ferré, Vincent Flückiger

Harpsichord

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Andreas Urweider

Recording & editing

Recording date

20/03/2015

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Johann Christoph Gottsched, 1727

First performance

Funeral of Queen Christiane Eberhardine of Saxony,

17 October 1727, Leipzig

In-depth analysis

The preparations for this performance, however, were long and fraught with sensitive religious-political issues. The queen, born into the house of Brandenburg-Bayreuth, had remained true to the Lutheran faith throughout her life, unlike her husband August the Strong, who had converted to Catholicism upon ascending the Polish throne. Rejected by the king, Christiane lived out the later years of her life alone in the palace “Schloss Pretzsch”. And while the court-decreed national mourning period can be easily understood as a political convention, the queen’s Protestant subjects lamented most sincerely the loss of their valiant sister in faith. As such, the prestigious ceremony at the University of Leipzig was organised under the initiative of student Hans Carl von Kirchbach, who succeeded in engaging two of the city’s leading artists: Gottsched, the “prince of poets”, and Bach, the Thomascantor. The project, however, stoked the ire of Görner, the organist of St Nicholas Church, who was responsible for the University’s regular music – Kirchbach virtually had to pay the organist to cede his right to perform. And finally, there were artistic hurdles to overcome: Gottsched’s learned, ten-verse ode had to be reworked into a cantata libretto “in Italian style”, replete with recitatives and arias. These efforts, however, were well rewarded. Bach – who led the performance from the harpsichord – composed an exceptionally artistic work, whose exquisite instrumentation and noble tenor no doubt evoked an extraordinary impression in a church that, right down to the organ, was completely draped in black.

Set in the tragic key of B minor, the introductory chorus perfectly captures the essence of courtly funeral music through its elegant dotted rhythms and splendid orchestration of flutes, oboes d‘amore, strings, violas da gamba and lutes, not to mention an incessantly “chiming” continuo. The intense, declamatory choir setting thus speaks to the heart of the listener and retrieves Gottsched’s elaborate poetry of “Salem’s starry heavens” back down to the earthly realm. Two further choral movements – the two-part fugue “In thee, thou model of great women”, directly before the eulogy, and the closing chorus “No, royal queen! Thou shalt not die” – embrace the purpose of the funeral by celebrating the royal “keeper of the faith” and proclaiming her eternal remembrance, while also acting as structural pillars for the composition. The swirling gigue of the closing chorus appears to be a musical rendition of the transient and fleeting nature of life, while the libretto sings on undeterred of a vibrant posterity, thus lending the setting a unique tension.

In keeping with the noble subject of the work, all recitatives are accompanied and feature changing obbligato instruments. The soprano recitative no. 2 (“Thy Saxons, like thy saddened Meissen”) and the alto recitative no. 4 (“The tolling of the trembling bells”) are a testament to Bach’s ability to employ even clichéd compositional formulas such as “funeral bells” and “lamentations” with a mastery that transcends all time. Indeed, the sighing windinstrument gestures above the contained continuo motive in the tenor recitative no. 6 and the delicately balanced three-part form of bass recitative no. 9 convey a heartfelt grief that disregards all decorum.

In the arias, Bach gives expression to the highly metaphorical language of the libretto, yet without compromising the work’s expansive lines. Regardless of whether he is depicting the “muting of the lyres” through a string setting punctuated with rests (soprano aria), shrouding the “contended dying of our lady” in elegant viola da gamba lines (alto aria), or constructing “eternity’s sapphiric house” in an exquisitely layered three-choir combination of transverse flute, strings and continuo, violas da gamba and lutes (tenor aria), Bach addresses the heart, ear, mind and soul of the listener throughout the work. When Leipzig’s city chronicler Vogel declared Bach’s composition to be “sublime music”, this was a most rare compliment. That Bach reused parts of the funeral music in his St Mark Passion (of which only the libretto survives), is, however, entirely unsurprising in light of their related themes and affects.

Libretto

Erster Teil

1. Chor

Laß, Fürstin, laß noch einen Strahl

aus Salems Sterngewölben schießen,

und sieh, mit wieviel Tränengüssen

umringen wir dein Ehrenmal.

2. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Dein Sachsen, dein bestürztes Meißen

erstarrt bei deiner Königsgruft;

das Auge tränt, die Zunge ruft:

Mein Schmerz kann unbeschreiblich heißen!

Hier klagt August und Prinz und Land,

der Adel ächzt, der Bürger trauert,

wie hat dich nicht das Volk bedauert,

sobald es deinen Fall empfand!

3. Arie (Sopran)

Verstummt, verstummt, ihr holden Saiten!

Kein Ton vermag der Länder Not

bei ihrer teuren Mutter Tod,

o Schmerzenswort! recht anzudeuten.

Verstummt, verstummt, ihr holden Saiten!

4. Rezitativ (Alt)

Der Glocken bebendes Getön

soll unsrer trüben Seelen Schrecken

durch ihr geschwungnes Erze wecken

und uns durch Mark und Adern gehn.

O, könnte nur dies bange Klingen,

davon das Ohr uns täglich gellt,

der ganzen Europäerwelt

ein Zeugnis unsres Jammers bringen!5

5. Arie (Alt)

Wie starb die Heldin so vergnügt!

Wie mutig hat ihr Geist gerungen,

da sie des Todes Arm bezwungen,

noch eh er ihre Brust besiegt.

Wie starb die Heldin so vergnügt!

6. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Ihr Leben ließ die Kunst zu sterben

in unverrückter Übung sehn;

unmöglich konnt es denn geschehn,

sich vor dem Tode zu entfärben.

Ach selig! wessen großer Geist

sich über die Natur erhebet,

vor Gruft und Särgen nicht erbebet,

wenn ihn sein Schöpfer scheiden heißt.

7. Chor

An dir, du Fürbild großer Frauen,

an dir, erhabne Königin,

an dir, du Glaubenspflegerin,

war dieser Großmut Bild zu schauen.

Zweiter Teil («Nach gehaltener Trauerrede»)

8. Arie (Tenor)

Der Ewigkeit saphirnes Haus

zieht, Fürstin, deine heitern Blicke

von unsrer Niedrigkeit zurücke

und tilgt der Erden Dreckbild aus.

Ein starker Glanz von hundert Sonnen,

der unsern Tag zur Mitternacht

und unsre Sonne finster macht,

hat dein verklärtes Haupt umsponnen.

9. Rezitativ (Bass)

Was Wunder ists? Du bist es wert,

du Fürbild aller Königinnen!

Du mußtest allen Schmuck gewinnen,

der deine Scheitel itzt verklärt.

Nun trägst du vor des Lammes Throne

anstatt des Purpurs Eitelkeit

ein perlenreines Unschuldskleid

und spottest der verlaßnen Krone.

Soweit der volle Weichselstrand,

der Niester und die Warthe fließet,

soweit sich Elb’ und Muld’ ergießet,

erhebt dich beides, Stadt und Land.

Dein Torgau geht im Trauerkleide,

dein Pretzsch wird kraftlos, starr und matt;

denn da es dich verloren hat,

verliert es seiner Augen Weide.

10. Chor

Doch, Königin! du stirbest nicht,

man weiß, was man an dir besessen;

die Nachwelt wird dich nicht vergessen,

bis dieser Weltbau einst zerbricht.

Ihr Dichter, schreibt! wir wollen’s lesen:

Sie ist der Tugend Eigentum,

der Untertanen Lust und Ruhm,

der Königinnen Preis gewesen.