Gott fähret auf mit Jauchzen

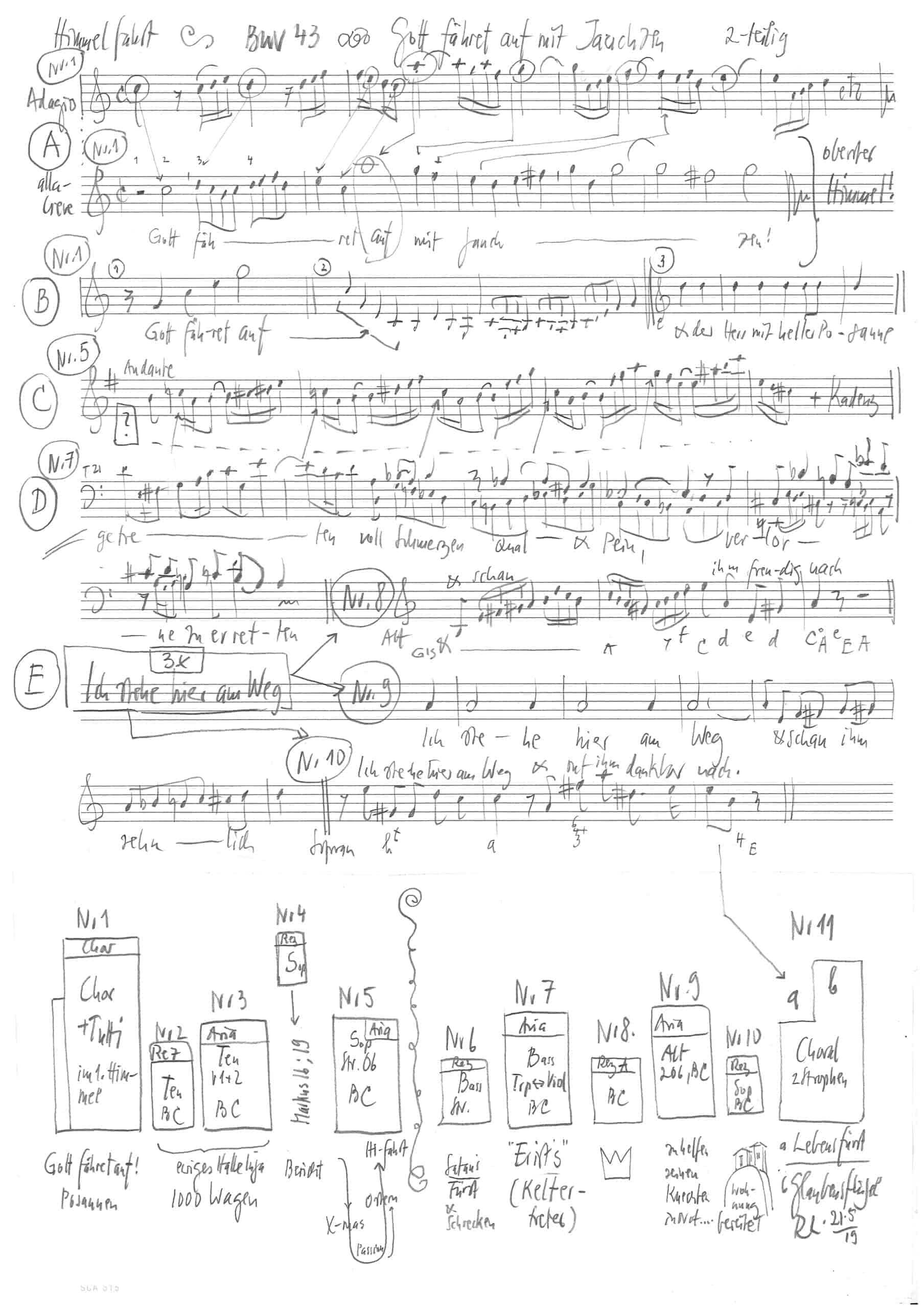

BWV 043 // for Ascension

(God goeth up with shouting) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, trumpet I-III, timpani, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Larissa Bretscher, Linda Loosli, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Anna Walker, Mirjam Wernli-Berli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Damaris Rickhaus, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Raphael Höhn, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Simón Millán, Valentin Parli, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Trumpet

Lukasz Gothszalk, Nicolas Isabelle, Alexander Samawicz

Timpani

Laurent de Ceuninck

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Dirk Börner

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Christoph Drescher

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/05/2019

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

First performance

30 May 1726, Leipzig

Text

Psalm 47:6–7 (movement 1); Mark 16:19 (movement 4); Johann Rist (movement 11); anonymous (Herzog Ernst Ludwig von Sachsen-Meiningen; movements 2, 3, 5–10)

In-depth analysis

First performed for Ascension Day in 1726, cantata BWV 43 is associated with a Thuringian-Saxon network of relationships that links Bach’s cantatas from that year to texts from Meiningen as well as to compositions by his cousin Johann Ludwig Bach, who was a resident of that city. Indeed, both composers employed verses that had been printed in numerous editions after 1704 and that were most likely penned by Prince Ernst Ludwig of Meiningen; movements five to ten of this cantata are based on such works. In the first half of 1726, Johann Sebastian furthermore alternated between performing his own works and sacred compositions by Johann Ludwig. These cantatas typically employ two Bible dictums, one each from the Old and New Testament.

The two-part introductory chorus opens with an adagio introduction that, in its stylistic similarity to the overture from the C Major Suite BWV 1066, captures the moment of stillness and calm preceding Christ’s ascension. At the transition to the brisk allabreve section, the first trumpet opens with an impressive fanfare over the resounding string passages, after which the tutti instrumentalists and choir enter with block-like calls and melismatic coloraturas illustrating the word “Jauchzen” (jubilation). This compact musicmaking flows into a powerful chorus on the words “Lobsinget Gott!” (Sing praise to God!) ere the freely polyphonic orchestral gala draws to a thrilling, clamorous finish.

The tenor recitative features what is termed an “aufmerksame Seele” (attentive soul), who, in awestruck contemplation of the heavenly host accompanying Christ’s ascension, rhapsodises with rhetorical questions in praise of God. The ensuing aria, in swift 3⁄ 8 metre, opens with a fleet-footed semiquaver figure for two unison violins over a light, swinging continuo accompaniment that sets the scene for the entry of the soloist, whose compact melody is based on the key notes of the cascading string figure. In this efficient movement, the music’s dramatic focus is less the crowd of “thousands on thousands” (from Psalm 68) who accompany the victorious king, than the earth-shattering pace of the Ascension.

The following gospel passage from Mark 16:19 is presented in a short and unpretentious soprano recitative, ere the aria, a surprisingly elegiac E minor setting accompanied by oboes and strings, gives expression to the parting sorrow of those left behind. Considering the bell-like clarity of the boys’ voices in Bach’s St Thomas choir, this no doubt made for a highly poignant moment that paved the way for the sermon.

The second part of the cantata opens with a contemplation of the heroic triumph of Christ, who is here addressed as the “hero of heroes” in a resonant recitative conceived for a powerful bass voice and agile string accompaniment. In the following bass aria, the trumpet responds with a highly exposed obbligato that is at once heroic and cantabile in style. (It is perhaps no coincidence that this exceedingly difficult part was transferred to the violin for a later performance; we have included the charming alternative arrangement as a bonus track on this CD, together with its preceding recitative.) In this industrious aria-trio setting, the tone is characterised by the wearisome “treading of the winepress” – its combined notion of crucifixion, resurrection and ascension audibly demands superhuman strength. The da capo of the aria, by contrast, is limited to the opening ritornello; it is possible that Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, who at the Cologne musical festival of 1838 performed BWV 43 as the centrepiece of an ascensionpasticcio of Bach’s music, was inspired to make similar abridgements in his arrangement of the master’s St Matthew Passion.

Entrusted to the alto, the final recitative and aria pairing is introspective in style. For its part, the recitative reveals the auspicious message that because Christ as the first of the resurrected faithful wears the crown of life, the pious still confined to an earthly existence can look up to him in confidence. This atmosphere of blissful anticipation is embodied in the aria by a pair of oboes, whose gentle melodic figures help incorporate in a consoling whole both the edgy bass part and a text that, at least in part, calls for wrathful destruction of the enemy and dwells on the woes of earthly privation. After the closing soprano recitative, which evokes the promise of a final dwelling place with God and thus transforms all sorrowful parting into liberated gratitude, the two-verse closing chorus unifies the message of the Feast of the Ascension with archaic simplicity. While it is uncertain whether Bach intended the use of brass instruments in this movement, their inclusion in our recording transforms the closing section into a climactic celebration of a liturgical theatre designed for a faithful congregation.

Libretto

1. Chor

Gott fähret auf mit Jauchzen

und der Herr mit heller Posaunen.

Lobsinget, lobsinget Gott,

lobsinget, lobsinget unserm Könige.

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Es will der Höchste sich ein Siegsgepräng bereiten,

da die Gefängnisse er selbst gefangen führt.

Wer jauchzt ihm zu?

Wer ists, der die Posaunen rührt?

Wer gehet ihm zur Seiten?

Ist es nicht Gottes Heer,

das seines Namens Ehr,

Heil, Preis, Reich, Kraft und Macht

mit lauter Stimme singet

und ihm nun ewiglich ein Halleluja bringet.

3. Arie — Tenor

Ja tausend mal tausend begleiten den Wagen,

dem König der Kön’ge lobsingend zu sagen,

daß Erde und Himmel sich unter ihm schmiegt

und was er bezwungen, nun gänzlich erliegt.

4. Rezitativ — Sopran

Und der Herr, nachdem er mit ihnen

geredet hatte, ward er aufgehaben gen

Himmel, und sitzet zur rechten Hand

Gottes.

5. Arie — Sopran

Mein Jesus hat nunmehr

das Heilandwerk vollendet

und nimmt die Wiederkehr

zu dem, der ihn gesendet.

Er schließt der Erde Lauf,

ihr Himmel, öffnet euch, und nehmt ihn

wieder auf!

6. Rezitativ — Bass

Es kommt der Helden Held,

des Satans Fürst und Schrecken,

der selbst den Tod gefällt,

getilgt der Sünden Flecken,

zerstreut der Feinde Hauf;

ihr Kräfte, eilt herbei und holt den Sieger auf.

7. Arie — Bass

Er ists, der ganz allein

die Kelter hat getreten

voll Schmerzen, Qual und Pein,

Verlorne zu erretten

durch einen teuren Kauf.

Ihr Thronen, mühet euch

und setzt ihm Kränze auf!

8. Rezitativ — Alt

Der Vater hat ihm ja

ein ewig Reich bestimmet:

Nun ist die Stunde nah,

da er die Krone nimmet

vor tausend Ungemach.

Ich stehe hier am Weg

und schau ihm freudig nach.

9. Arie — Alt

Ich sehe schon im Geist,

wie er zu Gottes Rechten

auf seine Feinde schmeißt,

zu helfen seinen Knechten

aus Jammer, Not und Schmach.

Ich stehe hier am Weg

und schau ihm sehnlich nach.

10. Rezitativ — Sopran

Er will mir neben sich

die Wohnung zubereiten,

damit ich ewiglich

ihm stehe an der Seiten,

befreit von Weh und Ach!

Ich stehe hier am Weg,

und ruf ihm dankbar nach.

11. Choral

Du Lebensfürst, Herr Jesu Christ,

der du bist aufgenommen

gen Himmel, da dein Vater ist

und die Gemein der Frommen,

wie soll ich deinen großen Sieg,

den du durch einen schweren Krieg

erworben hast, recht preisen

und dir gnug Ehr erweisen?

Zieh uns dir nach, so laufen wir,

gib uns des Glaubens Flügel!

Hilf, daß wir fliehen weit von hier

auf Israelis Hügel!

Mein Gott! wenn fahr ich doch dahin,

woselbst ich ewig fröhlich bin?

Wenn werd ich vor dir stehen,

dein Angesicht zu sehen?

Christoph Drescher

“Sing praises to God, sing praises to our King.”

The choir opens Bach’s cantata BWV 43 with this call. When oboes, trumpets and timpani accompany the choir, the music seems particularly energetic with festivity and joy – and in a joyful mood one wants to join in this singing of praise.

Johann Sebastian Bach wrote the cantata for Ascension Day. For Bach, as for many of his contemporaries, this was obviously an important feast day – four cantatas alone have been preserved by him for this occasion, and time and again he invested new energy and creativity in celebrating Ascension Day. These are very festive works that can be found in the cantata vintages from 1724 to 1726 for this occasion – and they are crowned by the Ascension Day Oratorio “Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen” (Praise God in His Realms), written in 1735.

In 1726, when this cantata was written, Bach not only performed his own music, but also presented the cantatas of his cousin Johann Ludwig Bach in Meiningen in Leipzig, among others. Their unusual form with the central setting of a poem is also found in Bach’s Cantata 43. But for Ascension Day, he did not fall back on existing music by his cousin or another composer he held in high esteem: with a work of his own, he wanted to “sing praises to God, our King” and do so with a large cast of trumpets, timpani and oboes.

Now the fascination of the Ascension can hardly come as a surprise. Even if it is not the highest of the Christian feasts, Jesus ascending to God in heaven is hard to beat in terms of impressive imagery. And it really is a unique story that comes to an end here. The soprano states it clearly in her aria:

“My Jesus has now / completed the work of salvation

And takes the return / To the one who sent him.”

So the story of Jesus’ work on earth has come to its conclusion, so that the Son of God can return to heaven. This is a powerful statement that should give the listener certainty in his faith in the work of the Saviour and in the existence of God. It is all the more astonishing that this joyful message also leaves room for question marks. For in the concluding chorale Bach has the choir plead:

“Give us the wings of faith!”

And he asks both longingly and impatiently:

“When shall I stand before thee / To see thy face?”

With these words, written in 1641 by the Lutheran preacher Johann Rist, the cantata ends in a heartfelt wish of faith – written 300 years ago, of course, in a deep certainty when Christianity was the norm of our community.

In my homeland, which was also Bach’s home, this is no longer the case today.

Ascension Day in Bach’s homeland, Thuringia, is above all Father’s Day. Men like to go hiking on this holiday, sometimes with handcarts in which they pull crates of beer behind them. This very profane image does not want to fit in at all with the heavenly music we have just heard. And yet it works as an illustration of a question that concerns me as a Bach concert organiser, but also many Bach interpreters: What does Bach’s music say to people when they no longer believe? What power does the music have when, with the disappearance of faith, it seems to have been deprived of its primary level of effect? And what can Bach’s music perhaps achieve that the Christian faith in its representation by the church is sometimes no longer able to do today?

These questions may arise less drastically in Trogen and in our conspiratorial Bach community. And yet I believe that even we “Bach maniacs” should remember this from time to time: As incomparably beautiful as this music is, it is still first and foremost a tool, a means to proclaim a message. Bach’s primary task as cantor and composer was to follow the liturgy and the church year, to write with his cantatas ultimately a kind of “soundtrack” for the communication of the Christian message in worship. And so, despite all the complexity of the music, it was always first and foremost about the text, which the music was supposed to help convey and better understand.

If we want to better understand why this music was written by Bach 300 years ago and why it was able to have such a lasting effect, it is worthwhile to attempt a journey back in time to the early 18th century. Whether in Arnstadt or Mühlhausen, in Weimar or later in Leipzig – we see deeply religious people before us, people who needed faith not least to accept the inevitable blows of fate in their lives. Johann Sebastian Bach lost almost a dozen children in the course of his life: How can a person endure that without a trust in God’s redemption?

Now, the pious people of Bach’s time were secure in their faith, they were firmly anchored in their religious world view – and yet they could not have been prepared for what Bach provided them with in the way of “musical packaging” for the Christian message. Let us imagine the churches of that time in their immense size, in which the message of God was heard in summer as well as in the freezing cold winter – and then we hear, for example, the “Erbarme dich” from the St. Matthew Passion, which lets the pain of Jesus’ suffering penetrate so directly into our hearts. This must have been an incredible experience, to allow so much emotion in a world that could actually only be endured in the pragmatism of heavy everyday life as well as reverent faith. And so it is often these arias, which detach themselves from the action of a passion or an oratorio and devote themselves entirely to the appreciation of a feeling, which we – then as now – find breathtaking and which literally draw us into the world of thought and feeling of the biblical story.

This is by no means only about sorrow and suffering: when the recognition, the seeing of the Lord is celebrated, as the bass does in his aria of Cantata 43, then this can only be accompanied by a clearly shining trumpet, which is able to underline the joy, the power of the “He is”.

What an incredible experience it must have been to hear this music and to be reached by it 300 years ago. Of course, it was a matter of course to be a Christian and to believe – but to allow feelings in this reverence, to feel sadness, emotion, joy and at times to let them become an almost physical experience, Bach’s music was able to make a great contribution to this.

But what about today?

Bach’s music has retained its effect even after 300 years. We all know and feel that Bach’s music reaches us, triggers something in us. This is not only true of the sacred works. The French journalist Philippe Lancon, who survived the “Charlie Hebdo” attack in 2015 with serious injuries, reports in his moving book “Der Fetzen” (The Tatter) about the difficult path back to life, in which the peace in Bach’s music and the Goldberg Variations helped him considerably. There are many such stories; we all have our own experiences of the comfort and peace that Bach can give.

And Cantata 43 also speaks of this consolation, of this empathy, when the contralto sings of how Christ helps his servants “out of misery, distress and shame”. It speaks of us, of warmth and readiness to help, which we accept and reciprocate when – according to the text of the aria – we stand on the road and look longingly after Christ.

What a beautiful, touching image!

When people without a Christian background or any previous musical training ask me which Bach concert they should attend as an introduction, I like to send them to the St Matthew Passion. The – yes, quite physical – experience of this three-hour setting of the Passion of Jesus seems to me more suitable than, say, an instrumental concert, which is easier to resist, which one might simply “find beautiful”. The power of the work and the message has made many a person leave the concert with tears in their eyes, forgetting the time as well as reservations about the content or the type of music.

So what is the effect that is able to grip us so directly? Is it “only” the unique music or is it also a Christian message that is conveyed through it? It is quite easy to try this out by simply leaving out the sung text in the sacred works. There are certainly ensembles that play “Bach without words”. Or imagine the opening chorus of our Cantata 43 sung in “Lalala”, what remains of the effect of this music?

This question is meant quite openly. We German speakers probably agree that the textual level is of great importance. In fact, Paul McCreesh, the director of the Gabrieli Consort and a renowned Bach interpreter, told me after his performance of the St. Matthew Passion this year that the text was ultimately dispensable in view of the immense strength and power of the composition. But is that so? And how do I interpret the music if I miss the level of meaning of the text?

For me, at any rate, this question clearly shows that Bach’s music also functions as a sermon. His music is so open, so clear and disarming that it actually leaves no doubt about the meaning of the text and thus makes it possible for some people to accept the message in the first place.

This is perhaps even more important today than in Bach’s time, because Bach naturally wrote his music in the expectation of a believing listener. But the fact that it is still effective today and also reaches non-believers says a lot about its quality and about the inseparability of message and music.

“Ja tausend mal tausend begleiten den Wagen”,

is the text of the tenor aria in Cantata 43.

rarely speak of such magnitudes today in secular East Germany, where I live: Only a minority still feel they belong to the church. And yet people come to our concerts, listen to the texts of Picander, Franck or Luther and are apparently ready to engage with a message for which they otherwise lack faith.

As an organiser, I experience that cantatas or passions in churches attract far more people than performances in concert halls. “That just belongs in church”, even non-denominational visitors say. Our audiences are even grateful not to clap after a Passion on Good Friday, but merely to rise silently in thanksgiving and take with them the story they have just experienced. But is it a purely cultural-historical perception, a tradition that leads to people preferring to sit freezing on hard wooden benches rather than in a tempered concert hall with good acoustics? In the recent past, the feuilleton has critically referred to them as “Bach Christians”, this bourgeois stratum that no longer calls itself religious, but nevertheless does not want to miss the tradition of the Christmas Oratorio in December, a Passion before Easter and perhaps even a Sunday cantata on the radio. But is that a negative thing?

When the American musicologist Michael Marissen published his book on Bach and religion “Bach and God” a few years ago, he was asked by the “New York Times” why he had chosen this title in this order. His laconic answer: “Bach & God? That’s redundant. But if it’s a contest, we name the winner first.”

Now, of course, this competitive juxtaposition is hardly meant seriously. But we can certainly take a message from it: Bach, with his music, still has the power today (or more than ever?) to provide answers and comfort. And if we are united in faith in Bach, we are ultimately also united in faith in God, whatever we call him. From an ecclesiastical point of view, this can be regretted as “too little” or “too unspecific” – or it can be seen as an opportunity, since the religiously unattached listener has a much greater opportunity to hear the message of Christ anew and to accept it for himself.

“If there is anyone to whom Bach owes everything, it is God,” wrote the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran. This may sound a little blasphemous, but at its core it is perhaps Bach’s truly great legacy:

Where the Christian religion comes up against the limits of our modern life, Bach’s music finds the right answers. And if we accept Bach’s work as an inseparable event of text and music and do not play theological and artistic-aesthetic perspectives off against each other, then we can probably find a gap for ourselves and our souls in precisely that indeterminacy between art and religion.

At this year’s Thuringian Bach Weeks, it was a very moving moment for me when, after his concert in the Georgenkirche in Eisenach, a conductor stood almost shaken at Bach’s baptismal font and said what great luck it was that this little baby, baptised there on 23 March 1685, had simply survived. He himself, he said, would certainly not be a musician today otherwise. What I have been asking myself ever since: how many of us would still be Christians today?

“I’m standing here by the road and I’m looking at him eagerly”,

is the recurring line of the poem that Bach set to music in the second half of our cantata. We understand this longing for meaning, for inner peace and redemption today just as we did in 1724, even without the basis of Christian faith. What remains is the search for, the hope in something higher, in God. And this then again has something of that power which already gripped the pious listener 300 years ago.

Bach wrote Soli Deo Gloria – to God alone be the glory – under many of his works, not only under church music. Perhaps there is no need to translate and explain this at all. Bach’s music explains everything higher from itself.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).