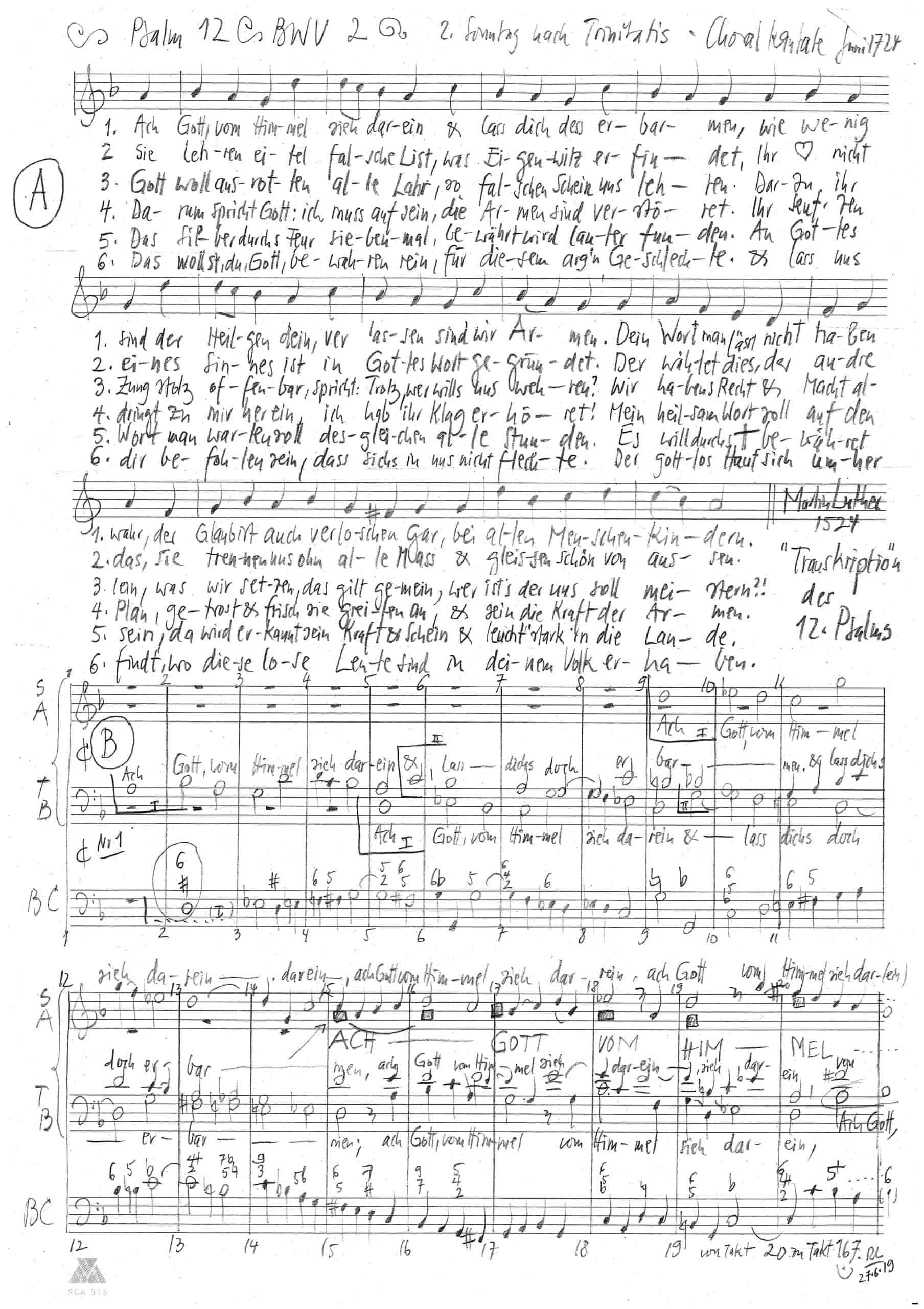

Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein

BWV 002 // For the Second Sunday after Trinity

(Ah God, from heaven look on us) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, trombone I-III, cornett, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel, Maria Weber, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Katharina Jud, Dina König, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Tiago Oliveira, Christian Rathgeber, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Claire Foltzer, Elisabeth Kohler, Marita Seeger, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Olivia Schenkel

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Shuko Sugama

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Philipp Wagner

Cornett

Frithjof Smith

Trombone

Simen van Mechelen, Henning Wiegräbe, Joost Swinkels

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rainer Hank

Recording & editing

Recording date

28/06/2019

Recording location

Speicher AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

First performance

18 June 1724, Leipzig

Text

Martin Luther (movements 1, 6: based on psalm 12); anonymous (movements: 2–5)

In-depth analysis

For his chorale cantata cycle of 1724/25, Johann Sebastian Bach conceived an ambitious opening gesture: each of the first four cantatas features a distinctive opening chorus with the melody set in a different voice – from soprano through to bass – unlike the later cantatas of the cycle, which regularly feature the cantus firmus in the soprano voice.

For the introductory chorus, a setting of the solemn early Reformation hymn “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein” (Ah God, from heaven look on us), Bach employs the unmistakably “antiquated” form of a vocal motet, in which he doubles the vocal parts with trombones and strings and assigns the augmented cantus firmus to the alto voice. Opening with a prominent “Phrygian” semitone interval, the movement’s modal tonality and five-voice writing (achieved through independent thematic material in the continuo) are well-suited to the archaic aura. That Bach confronts this venerable sound with his modern approach to harmonisation only enhances the setting’s curious and distinct appeal.

In the tenor recitative, the vocal soloist and continuo present the first line word for word in close canon, making for an opening that retains its connection to the chorale, despite the setting’s declamatory, soloistic form. By contrast, the ensuing lines present kaleidoscopic images of Baroque transience that, illustrated by brusque dissonances in the continuo accompaniment, denounce every departure from the Gospel as the hubris of mortals led astray by “törichte Vernunft” (reason’s foolishness).

For a request such as “Tilg, o Gott, die Lehren, so dein Wort verkehren” (God, blot out all teachings, which thy word pervert now), Bach could easily have employed a thundering bass soloist and resounding trumpets. Instead, he set the aria for a chamber ensemble of alto soloist, continuo and solo violin, whose succinct bass formulae and incisive figures call to mind the zealous workings of a well-oiled bureaucracy, where the sharp interrogation techniques, as embodied by the high alto part, vanquish all heretics and “rabble spirits”. That Bach consciously chose to throw tradition on the scale in the interest of resolving current theological controversies in the counter-Enlightenment sense of Lutheran orthodoxy is made audible in the chorale quotes of the middle section.

This distressing disunity leaves the suffering souls of this world in sore need of kindly empathy – which the bass recitative with string accompaniment delivers in spades. Despite the shimmering radiance of the orchestra, the opening lines still speak of the cross, woe and torture, whereas the second section praising the merciful acts of the Highest is lent an encouraging arioso style. In the equally energetic and humble closing gesture, the notion that the true “Kraft der Armen” (strength of the wretched) lies in the “heilsames Wort” (healing word) is lent poignant expression.

That trials and transformation are interwoven in a salvation-historical sense is already made manifest in the following aria through the contrasting timbres and contrary motion of the orchestral prelude. “Durchs Feuer wird das Silber rein” (The fire doth make the silver pure) – like a vein of precious metal formed in rock, the tenor voice, extolling patience and fortitude, flows undeterred towards its purpose and spiritual renewal.

The closing chorale “Das wollst du Gott bewahren rein” (That wouldst thou, God, untainted keep) shows with singular clarity that, over and above the quality of their text setting, the music in Bach’s chorale movements has an inherently stabilising effect.

Although traces of the libretto’s bitter struggle are echoed in the chordal progressions, they are outweighed by the powerful, unifying character of communal singing – a practice transcending time and musical fashion – and the vibrant modal cadence that closes the setting.

Libretto

1. Chor

Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein

und laß dichs doch erbarmen,

wie wenig sind der Heilgen dein,

verlassen sind wir Armen.

Dein Wort man nicht läßt haben wahr,

der Glaub ist auch verloschen gar

bei allen Menschenkindern.

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Sie lehren eitel falsche List,

was wider Gott und seine Wahrheit ist;

und was der eigen Witz erdenket

– o Jammer! der die Kirche schmerzlich kränket –

das muß anstatt der Bibel stehn.

Der eine wählet dies, der andre das,

die törichte Vernunft ist ihr Kompaß;

sie gleichen denen Totengräbern,

die, ob sie zwar von außen schön,

nur Stank und Moder in sich fassen

und lauter Unflat sehen lassen.

3. Arie — Alt

Tilg, o Gott, die Lehren,

so dein Wort verkehren!

Wehre doch der Ketzerei

und allen Rottengeistern;

denn sie sprechen ohne Scheu:

Trotz dem, der uns will meistern!

4. Rezitativ — Bass

Die Armen sind verstört,

ihr seufzend Ach! ihr ängstlich Klagen

bei soviel Kreuz und Not,

wodurch die Feinde fromme Seelen plagen,

dringt in das Gnadenohr des Allerhöchsten ein.

Darum spricht Gott: Ich muß ihr Helfer sein!

Ich hab ihr Flehn erhört,

der Hilfe Morgenrot,

der reinen Wahrheit heller Sonnenschein

soll sie mit neuer Kraft,

die Trost und Leben schafft,

erquicken und erfreun.

Ich will mich ihrer Not erbarmen,

mein heilsam Wort soll sein die Kraft der Armen.

5. Arie — Tenor

Durchs Feuer wird das Silber rein,

durchs Kreuz das Wort bewährt erfunden.

Drum soll ein Christ zu allen Stunden

in Kreuz und Not geduldig sein.

6. Choral

Das wollst du, Gott, bewahren rein

für diesem arg’n Gschlechte,

und laß uns dir befohlen sein,

daß sichs in uns nicht flechte.

Der gottlos Hauf sich umher findt,

wo solche lose Leute sind

in deinem Volk erhaben.

Rainer Hank

Dear Cantata Community

Today’s Bach cantata “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein” has thrown me into a whirlpool of contradictory feelings. As a Catholic, the cantata outraged me after I read that the underlying Lutheran Reformation chorale was used in Lübeck in 1529 as a kind of Protestant “flash mob” at the end of the Catholic service to sing down the Catholics. The thing worked, which then fascinates me a bit because it shows something about the power of music. As a friend of critical rationalism, the cantata upset me because of its condemnation of reason as “foolish”, which is hard to accept. As a journalist, however, I am surprised by the clear-sighted perception of the destructive effect of a world of “fake news”. It is a world where you cannot rely on anything or anyone.

I will give you impressions of this excitement of mine in the next fifteen minutes. In doing so, I want to concentrate on the tenor recitative “They teach vain false cunning”.

I.

I begin with “fake news”. The pivotal point for the cantata is Psalm 12, which – in the ecumenical unity translation – says: “Among men there is no more faithfulness. / They lie to one another, one to another, / With false tongues they speak.” Our tenor sings accordingly, “They teach vain false guile.”

Is this not our experience in the 21st century, where it has become unclear what is truth and what is a lie?[1] Trust that was once taken for granted is fading. Our tenor recitative is only superficially reassuring when it reminds us that everything has happened before. Of course: as long as people have been able to speak, they have lied to each other. We deceive each other, fall for others’ tricks and pretend to be what we are not. People have been spreading rumours, scheming and misleading each other since time immemorial. During the Italian Renaissance, princely courts maintained special chancelleries that invented false reports and spread them among the people. The psalmist knows this, the poet of our cantata knows this: “Among men there is no more faithfulness. / They lie to one another, one to another, / With false tongues they speak.”

But the machinery of deception is coming to a dangerous head in our present day. I quote Zachary Wolf. The man is digital director of the CNN television network. When asked why it is so difficult to report on Donald Trump as a journalist, he answers: “Because we never know what he means when he says words.” The producers of Fake News, one could say with the unknown poet of the cantata, are like gravediggers, who, although beautiful on the outside, only grasp stink and mustiness inside and let nothing but filth be seen. The connection between saying and meaning is destroyed, “because we never know what he means when he says words”.

Let me use an example that has become prominent, the so-called “Pizzagate conspiracy”, to make clear what I am thinking of: according to a legend spread during the 2016 American election campaign, members of the Democratic Party in America and the owners of a pizzeria in Washington were involved in the business of a child porn ring. This completely fabricated story was shared by conspiracy theorists on their websites, including a conspicuous number of Russian websites. The story caused a big stir because the case involved a civilian armed with an assault rifle who turned up at the pizzeria to investigate on his own as a kind of sheriff. The invention – a fiction – has real consequences!

The fact that conspiracies and slander based on fake news have such an easy game today is based on two circumstances: 1. putting news – whether true or untrue – into the world is easier than ever in the age of the internet. We journalists have dramatically lost our professionally proven monopoly on the production of “true” news. 2 In the echo chambers of the internet, conspiracy theories find it particularly easy to gain acceptance. This is mainly due to the dynamics of so-called information and conformity cascades. Instead of critical examination, it is all about self-affirmation and self-confirmation. In this cascade-like way, the freely invented gains high plausibility among those who are interested in believing it.

As a journalist, I want to despair because I have always trusted that the ethos of our profession is based not least on adherence to the rules of the trade. But at the same time, I cannot avoid noting that there is also a proximity between the logic of the mass media and the logic of populism: Dramatisation, emotionalisation, simplification and personalisation have become, perhaps to an exaggerated degree, the means of presentation of journalism, used to get attention for our texts in economically difficult times. Dramatisation, emotionalisation, simplification and personalisation are also genuine forms of articulation of populism. The media’s rules of attention and populist logic overlap. The proximity is striking, the similarity is irritating[2].

Have we journalists also allowed ourselves to be seduced – to quote Karl Popper – by the “call of the horde”?[3] We, who are only too happy to judge charlatans of fake news from above, would then be part of the problem ourselves and not (only) agents of the solution. The critics of the elks are often elks themselves!

II.

Let us come to reason.

What means do we have against a world of “fake news” in which “one lies to the other and there is no more loyalty among people”? For us children of the European Enlightenment, the answer is clear: we must emphatically hold on to the concept of truth. Of course, one can see the world one way or another, depending on one’s point of view and world view. But it is unseemly to give up the claim of wanting to compete with others for an appropriate world view. It is scandalous to suspend the claim to truth and to set ourselves up in the echo chambers of lies.

It is reason that has to serve the production of truth in the occidental tradition. Reason is what we call the ability to recognise – with the help of arguments and with reference to reasons. And with the willingness to let empiricism correct us. “If the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” is one of my favourite quotes from John Maynard Keynes. It’s antidote to all conformity cascades. One can also put it this way with the philosopher Jürgen Habermas, who just turned 90: Adhering to the claim to truth means bowing to the “unconstrained compulsion of the better, because plausible, argument”[4]. The unconstrained compulsion! This compulsion, it seems to me, is the decisive point that those who have allowed themselves to be seduced by the “call of the horde” refuse to accept. For they teach “vain false cunning”.

Why I am picking on reason here is obvious. The poet of the cantata libretto in the tradition of Luther’s critique of reason takes a completely different view from the European Enlightenment. For him, submission to the compulsion of truth-creating reason is precisely not salvation from the world of lies. On the contrary, the cantata poet considers reason itself to be the cause of divisive lies. He who chooses “foolish reason” as his compass, who follows only his own “wit”, that is, his intellect, will never arrive at the truth, but will leave behind only stink and mustiness, nothing but filth. “The one chooses this, the other that” – according to Luther, reason has led us into this disorder of arbitrariness. How could it deliver us from it?

There is a sheer endless theological literature on Luther’s concept of reason, which I do not want to bother you with here[5]. To summarise it casually: Luther thinks nothing at all of reason. He famously calls it “the highest whore the devil has”, also “Frau Hulda” and ironically “Mistress Reason and Metze”. Luther: “But the devil’s bride ratio, the beautiful Metze, (…) she is the highest whore the devil has. The other gross sins are seen, but reason no one can judge.” Luther needs this radically negative concept of reason so that on the other side the “grace worthy of salvation” can shine all the brighter. Reason only knows “idols” because God himself does not reveal himself to people through reason, but only through grace. The condemnation of reason is the price of the doctrine of justification.

I confess: at this point I am glad to be Catholic, because the Catholic tradition (from Thomas Aquinas to Karl Rahner) trusts reason (given to us by the Creator) with more knowledge of truth than the poet of our cantata libretto does. I also confess and repeat that I believe that in today’s world only an emphatic commitment to critical rationalism helps against the lying tribalism, the tribalism of the “call of the horde”. Demonising reason will get us nowhere. This was obviously felt by the much-maligned cultural Protestants in the 19th century, who are quoted in the programme booklet: “Only Mormons and Pietists can still be comfortable with such things” – said the German cellist and choirmaster Ludwig Bischoff in 1852.

In short and roughly summarised: Our cantata aptly describes the corrosive power of a world of lies, in which the connection between what is said and what is meant is broken. I agree with that. But I cannot follow the poet at all when he, in good Lutheran fashion, blames foolish reason for this disastrous situation. Rather, it would be better to recognise salvation in reason. Critical rationalism as the path to truth, that is the slogan.

III.

I could end with this. But I do not want to conceal a relativising irritation as a coda.

Is it not also the problem of our time that the “unconstrained compulsion to understand” (Habermas), the commitment to rational discourse has just become fragile and brittle? Is the “call of the horde” not also a protest movement against the arrogant reasonableness of the elites – that is, of us sitting here – who for our part exercise a compulsion, namely the compulsion of communicative reason, which we present as having no alternative and to which everyone must submit? Whoever does not do so has forfeited the right to belong, in the view of the elites. If the gatekeeper of reason only admits to discourse those who submit to reason, then discourse becomes protectionist. This can only be called “foolish”.

Coercion remains coercion, even if it is the coercion of reason. To this objection, Jürgen Habermas himself (albeit in a different context) gives a surprising answer inspired by Sören Kierkegaard, which is strangely reminiscent of our tenor recitative: “The individual is justified (…) if and because he knows himself to be loved by a ‘higher power’. When it passionately surrenders itself to faith (and thus not to reason, R.H.), yes, bids farewell to its ‘intellect’ and knows that its ‘selfhood’, which in any case fails in all action, is unavailingly secure.”[6]

So, out of despair that reason is no longer fulfilling its mission well today, should we then hope for faith after all – as the better alternative, so to speak? Seen this way, faith would at least be an “option” in times of lies and the dwindling persuasive power of reason[7]. At any rate, this is the sound of the supplication of the altarpiece in our cantata, which follows the tenor recitative: “Tilg, oh Gott, die Lehren, / so dein Wort verkehren!”

Let’s just listen to the cantata “Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein” a second time.

[1] My analysis of “fake news” joins the excellent essay by Romy Jaster and David Lanius, “Truth abolishes itself. How Fake News makes politics.” Reclam: Stuttgart, 2019.

[2] Following Niklas Luhmann (“The Reality of Mass Media”, Wiesbaden, 2004), the idea of the proximity between populism and media is developed by political scientist Paula Diehl in several works. Cf. Paula Diehl: “Why Do Right-Wing Populists Find So Much Appeal in Mass Media?” In: Dahrendorf Forum Hertie School of Governance, Berlin, 20 October 2017.

[3] Under the Popperian title “The Call of the Horde”, the Peruvian poet Mario Vargas Llosa has just presented his “intellectual biography” (Suhrkamp-Verlag: Frankfurt, 2019).

[4] Cf. on this, among others, Charles Larmore: Der Zwang des besseren Arguments. In: Lutz Wingert/Klaus Günther (eds.): Die Öffentlichkeit der Vernunft und die Vernunft der Öffentlichkeit. Festschrift for Jürgen Habermas. Suhrkamp-Verlag: Frankfurt, 2001, pp. 106-125.

[5] I only mention here from the secondary literature: Udo Kern: Zum Verhältnis von Glaube und Vernunft bei Martin Luther. In: Rainer Rausch (ed.): Glaube und Vernunft. How reasonable is reason? Hannover, 2014, p. 55/71. Karl-Heinz zur Mühlen: Der Begriff ratio im Werk Martin Luthers. In: ders.: Reformatorisches Profil. Studies on the work of Luther. Göttingen, 1995, pp. 154-173. Reinhold Rieger (ed.): Martin Luthers theologische Grundbegriffe. From “Lord’s Supper” to “Doubt”. Tübingen, 2017 (Reason: pp. 308-311). While the theological literature on Luther’s concept of reason is boundless, philosophers ignore the topic almost completely.

[6] I take this story from an article by the Tübingen philosopher Manfred Frank on Habermas’s 90th birthday in the “Zeit” of 13 June 2019. Habermas responds to Manfred Frank’s objection that reason is unstable in principle with the reference quoted here to Sören Kierkegaard and the belief in the love of a “higher power”, not, of course, without subsequently affirming that he personally could not subscribe to this way out of Kierkegaard.

[7] Hans Joas: Faith as Option. Future Possibilities of Christianity. Verlag Herder: Freiburg, 2012.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).