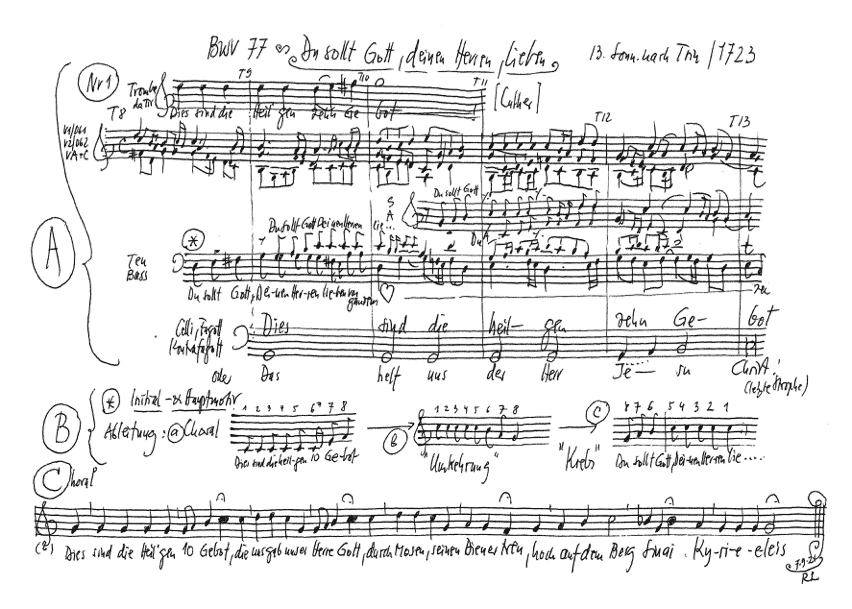

Du sollt Gott, deinen Herren, lieben

BWV 077 // For the Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Thou shalt thy God and master cherish) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Linda Loosli, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Anna Walker

Alto

Antonia Frey, Tobias Knaus, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Raphael Höhn, Zacharie Fogal, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Simón Millán, Jonathan Sells, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Ildikó Sajgó, Judith von der Goltz

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Guisella Massa

Tromba da tirarsi

Lukasz Gothszalk

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Laura Alvarado

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Contrabassoon

Ester van der Veen

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Iren Meier

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/09/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

22 August 1723 – Leipzig

Text

Luke the Evangelist 10:27 (movement 1); Johann Oswald Knauer (movements 2–5); Martin Petzold (movement 6)

In-depth analysis

First performed on 22 August 1723 in Bach’s first year as Thomascantor in Leipzig, the cantata “Du sollt Gott, deinen Herren, lieben” (Thou shalt thy God and master cherish) is a masterly reference to the work’s underlying Sunday pericope from Luke 10. Nonetheless, the opening movement focuses not on the parable of the Good Samaritan but on Christ’s double commandment to love God and one’s neighbour. Accordingly, for the introductory chorus, Bach chose to unite his setting of the dictum – which is inspired by the idea of an imitative succession – with the Luther hymn “Dies sind die heilgen zehn Gebot” (These are the holy Ten Commandments), thus highlighting the unity of the Old and New Testament and the emergence of the Christian law of love from the law of Moses. To this end, he not only overlaid the freely polyphonic vocal and string parts with a presentation of the chorale melody by a slide trumpet, but also derived the ascending main theme of the orchestral and choral material from the chorale motif. The elegiac character of the movement, distinctive from the very first continuo notes, expresses both the tenderness of Christ’s example of love and the nigh unattainable aspiration it represents, and this corrective to the Ten Commandments lends cohesion to the divergent soundscape.

The bass recitative opens by emphasising the first part of the commandment of love – the faithful heart’s turning to God. When God is experienced as the source of all spiritual joy and the true fire of the human spirit, then the submission owed to the Highest likewise, in the Lutheran sense, brings liberating proof of His favour and goodness, a notion Bach’s sonorous bass cantilena reinforces with fatherly assurance.

It is precisely because of this grace that the soprano aria, accompanied by two oboes, can present a heartfelt love song despite the muted A minor key: “Mein Gott, ich liebe dich von Herzen” (My God, with all my heart I love thee). Here, Bach aims to express a voluntary humility that asks that the lesson learned from the commandment be transformed into a lifelong, inspiring wellspring of love. Whereas Martin Luther struggled to provide a motivation for giving selflessly to one’s neighbour after renouncing the mandatory good deeds called for in the early Church’s Economy of Salvation, Bach, thanks to his consonant writing for the two oboes, is able to reveal this mystery of love as an already granted better life. In turn, such beautiful constellations prove true Luther’s conviction that the power of music surpasses the most eloquent of words.

Thus strengthened, the faithful can now commit to the second part of Jesus’ commandment of love – to love thy neighbour as thyself. Here, the libretto, based on a cantata cycle by Johann Oswald Knauer printed in Gotha in 1720, draws on the Sunday Gospel by pleading for an open “Samariterherz” (Samaritan heart), which is musically expressed in a friendly, descending gesture. In this tenor recitative accompanied by strings, Bach skilfully portrays this attitude – akin to a transformation of the inner self – word for word right up to the closing condition of “Gnade” (mercy) in sensitively rendered gestures and intervals.

Given this promised certainty, the following alto aria comes across as a veritable confutation – a deliberate, final discomfort – thus revealing itself as true to life. “Ach, es bleibt in meiner Liebe lauter Unvollkommenheit” (Ah, there bideth in my loving nought but imperfection still) – this all-too familiar disparity between thought and deed inspired Bach to one of his boldest interpretations. Here, the usually triumphant trumpet is employed in a deeply introspective setting that leaves the instrumentalist struggling, without any orchestral support, to persevere in the face of exposed descending leaps and conspicuous pauses. The attempt to nonetheless draw energy from the knowledge of one’s own failure takes on the air of a caricature – especially in the middle section that exposes all-too-human excuses – yet the music never abandons its tone of loving compassion.

Because Bach’s autograph score of the final chorale contains no text, scholars and performers have always been called upon to find a fitting verse for this music. In contrast to Carl Friedrich Zelter in the 19th century and to the New Bach Edition, we have decided (as suggested by Martin Petzold) to use the eleventh verse of the hymn “Herr, deine Rechte und Gebot” (Lord, your rights and your commandments), written by David Denicke in 1637, which conveys the acceptance of our own imperfection in a consoling, congregational song.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Du sollt Gott, deinen Herren, lieben von ganzem Herzen, von ganzer Seele, von allen Kräften und von ganzem Gemüte und deinen Nächsten als dich selbst.»

2. Rezitativ — Bass

So muß es sein!

Gott will das Herz vor sich alleine haben.

Man muß den Herrn von ganzer Seelen

zu seiner Lust erwählen

und sich nicht mehr erfreu’n,

als wenn er das Gemüte

durch seinen Geist entzündt,

weil wir nun seiner Huld und Güte

alsdenn erst recht versichert sind.

3. Arie — Sopran

Mein Gott, ich liebe dich von Herzen,

mein ganzes Leben hangt dir an.

Laß mich doch dein Gebot erkennen

und in Liebe so entbrennen

daß ich dich ewig lieben kann.

4. Rezitativ — Tenor

Gib mir dabei, mein Gott! ein Samariterherz,

daß ich zugleich den Nächsten liebe

und mich bei seinem Schmerz

auch über ihn betrübe,

damit ich nicht bei ihm vorübergeh

und ihn in seiner Not nicht lasse.

Gib, daß ich Eigenliebe hasse,

so wirst du mir dereinst das Freudenleben

nach meinem Wunsch, jedoch aus Gnaden geben.

5. Arie — Alt

Ach, es bleibt in meiner Liebe

lauter Unvollkommenheit!

Hab ich oftmals gleich den Willen,

was Gott saget, zu erfüllen,

fehlt mirs doch an Möglichkeit.

6. Choral

Ach Herr, ich wollte deine Recht und deinen

heilgen Willen, wie mir gebührte, deinem

Knecht, ohne Mangel gern erfüllen, so fühl

ich doch, was mir gebricht, und wie ich das

Geringste nicht vermag aus eignen Kräften.

Iren Meier

Where does the music go after it has been heard? A child’s question that never ceases to amaze me.

Where does the music stay after it has been heard? –

One possible answer is to listen further, into the silence. Experiencing and experiencing how the cantata continues to sound – in me, in us, spreads, settles: in our cells, in our heart, in our soul. Perhaps every note, every sound changes us. Perhaps it remains in us, the music,

including this wonderful performance, which each of us hears in his or her own way.

I hear in it a longing, a plea. To love God. And to love our neighbour. How can I do that – in my imperfection?

The recitative says:

Give me thereby, my God, a Samaritan’s heart,

that I may at the same time love my neighbour

and in his pain

I may also be deceived by him,

so that I do not pass by him

and not leave him in his distress.

That is the starting point and the core of this reflection, that is the sentence I have been thinking about in the last few weeks: In this, my God, give me a Samaritan’s heart.

Involuntarily, the parable of the Good Samaritan, which we heard about in the introduction and which I would like to touch on again, appears before the inner eye.

In the Gospel of Luke, we are told how Jesus explains to a scribe who his neighbour is:

“On the way down from Jerusalem to Jericho, a man was caught by robbers. They plundered him and left him seriously injured. A priest passed by, saw the injured man and went on without helping. A servant of the priest passed by just as carelessly. Only the third, a stranger, took pity, tended the man’s wounds and transported him on his mount to the inn.”

This third was the good Samaritan. He was the nearest to the wounded man.

In him beat the Samaritan heart.

The cantata holds this parable. And it has also engraved itself in our minds and hearts through the paintings of great painters. They all depict the Samaritan as a person who grasps, with both arms, who resolutely picks up the wounded, in some paintings it seems like an intimate embrace. No hesitation, no hesitating. Action.

Over these images is another: not far from Jerusalem and Jericho. The same landscape, the same land. It was in Nablus, in what is now occupied Palestine. I had interviewed a young university lecturer there. When I wanted to say goodbye, he asked: “Would you like to come to the hospital? My nephew is there. Karim.” – It was a very improvised, poor clinic. Many patients were lying in the corridor. White curtains separated the beds. White was the bandage around Karim’s head and also the boy’s face. His eyes were closed. A device beeped. – I stood there.

The uncle sat down on the bed, leaned forward and spoke into a motionless face: “Look, Karim, this is Iren. She comes from Switzerland. You know where Switzerland is, you’re so good at geography. It’s in the middle of Europe, next to Italy and France. You know the capital…”

A monologue that went on and on and produced no reaction. A monologue that Karim did not hear. Karim hadn’t heard for a week.

Ever since a soldier had shot him in the head on the way to school.

The boy was twelve years old. He loved his uncle, he loved school, he loved life.

When I think back, the minutes beside his sickbed turn into hours. I see myself standing there. Powerless, helpless.

Give me a Samaritan heart! … That I will not leave him in his distress. … Let me pick up the boy, put him in the car and take him somewhere where they can help him, where they have more possibilities. Let’s get past the checkpoints.

I see myself walking away, the bandaged head on the pillow getting smaller. Karim’s uncle says, “Thank you. It’s important that you were there. Be a witness, don’t look away. Report on it.”

I saw the badly injured little boy, didn’t pass by. But I didn’t lift him onto the horse, didn’t take him to the hostel.

Karim in Nablus is part of my story to this day, his shadow remains and the tenderness of that moment in the hospital room, his uncle’s voice and his love, interwoven with the hope for the miracle – which did not happen.

I have lived and worked for many years in areas where the need for Samaritan hearts is immense, because the suffering is so overwhelming, because so many people “fall prey”, are hurt, abused, humiliated.

As a journalist in war and conflict zones, I have met people who were in deepest need or danger, who needed help: Fugitives, displaced persons, persecuted, wounded, traumatised. Every single encounter has challenged me. I have reported on many of them. Telling their story always relieved me, at least I could do that. Then the powerlessness did not paralyse so much.

This did not help with Karim in Nablus. Nor with Zainab,

an Iraqi woman I met in Damascus at the time, who described to me for four or five hours how she had been tortured by American soldiers for weeks in Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad after the US invasion of Iraq.

I remember her monotone quiet voice, the endless pauses, the street noise coming through the window. And I still see her empty gaze, to this day, that gaze that all of a sudden became dark, insistent, holding me as if demanding an answer, an explanation.

She spared me nothing. Every detail of the torment was forced upon me, the exact description of human cruelty. All I wanted to do was leave, cover my ears, my eyes, forget the woman.

As in Nablus, I understood that afternoon in Damascus that in some situations I can do nothing, that I am only an extra, only one who listens.

Again and again I had to accept the limits of my possibilities: no horse, no hostel, no Good Samaritan.

But little by little I became aware that the alternative is not nothing. I learned that compassion and love of one’s neighbour are not only manifested in doing, but also in being.

I suspect that the American soldiers did not hate Zainab when they tortured her, this Iraqi woman unknown to them. It could be that they had no feelings towards her at all, but rather that what the English painter and poet John Berger put it like this was true:

“The opposite of love is not hate, it is separation.”

If I regard my fellow human being as the “other” who exists separately from me, with whom I have nothing to do, nothing in common, and whom I can therefore quite easily declare the “enemy” or the “stranger”. If I do not live in connectedness with everyone and everything, am not aware that we share everything, that I am an individual and always also the whole. The outer identity distinguishes us from each other, the inner one does not.

“Being means sharing”, says the natural scientist and philosopher Andreas Weber. “Sharing means being, on all levels, from the atom to our experience of happiness. Breathing is sharing, being in the body is sharing and loving is sharing.”

Taken to its logical conclusion, this means “I can only be because you are.” The neighbour is closer than near. You and I are one. And where the separative dissolves, compassion awakens. That tender feeling for life. For all living things. It is the place where the fundamental fragility of existence becomes palpable and our own vulnerability.

Perhaps it is the key – our own vulnerability, because it nurtures a sense of how the other is.

“I can only be because you are” – in this realisation beats the Samaritan heart. I no longer have to ask God for it. He has already given it to me.

It can beat anywhere. The neighbour is always right where we are. “Everywhere is holy ground,” says the Benedictine monk David Steindl Rast, “because every place can become a place of encounter, an encounter with the divine presence. As soon as we take off our shoes of being used to it and awaken to life, we realise: If not here, where else? When, if not now. Now, here or never and nowhere, we stand before the ultimate reality.”

Australian UN worker Sarah Copland was living in Beirut when the explosion in the port destroyed parts of the city and many lives on 4 August last year. She was in her living room feeding her two-year-old son Isaac. The force of the detonation shattered the windows of the flat and the glass penetrated the child’s small body, seriously injuring him. The mother rushed down to the street with her son, where total chaos reigned. At some point a driver stopped and raced them through the streets looking for a hospital that was still functioning. They finally found one and Isaac underwent emergency surgery. The doctors could not save him: the child died. When the mother tells about it, she always mentions the car driver who saw her in her distress and tried to do the impossible. And she always calls him the “good Samaritan”. Through him she experienced the greatest charity – in her greatest pain.

This Samaritan of Beirut could have been taken from the parable, a modern version, he too a doer, a plucker. The horse is his car, the hostel is the hospital.

Amina and Raza in Sarajevo taught me that sometimes it is enough to simply stop, to stop and to endure. The family had gone through the hardest times during the siege. The grandparents and the father did not survive the war. Raza, the mother, was alone with two adolescent children. When things could hardly go on any longer, we were able to support her a little so that Amina, the daughter, could study at all. It was no more than a gesture, a little solidarity. Years later, the two of them told us: The decisive thing for them was not the material help, but to know that there were people out there who were not indifferent to them, who were aware of their abandonment and their pain. Being alone in someone else’s thoughts can be the greatest help in times of need.

They called the self-evident the precious. They called the simplest things special.

I have heard similar things again and again from those who suffer war, violence and injustice. Only turning away, being forgotten, kills all hope.

When we don’t pass by our neighbour, then relationship develops. The American psychologist Virginia Satir finds words for this with which I would like to close this reflection. I read in them a beautiful description of the Samaritan heart:

“The greatest gift I can receive from someone is to be seen, heard, understood and touched. The greatest gift I can give is to see, hear, understand and touch the other.”

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).