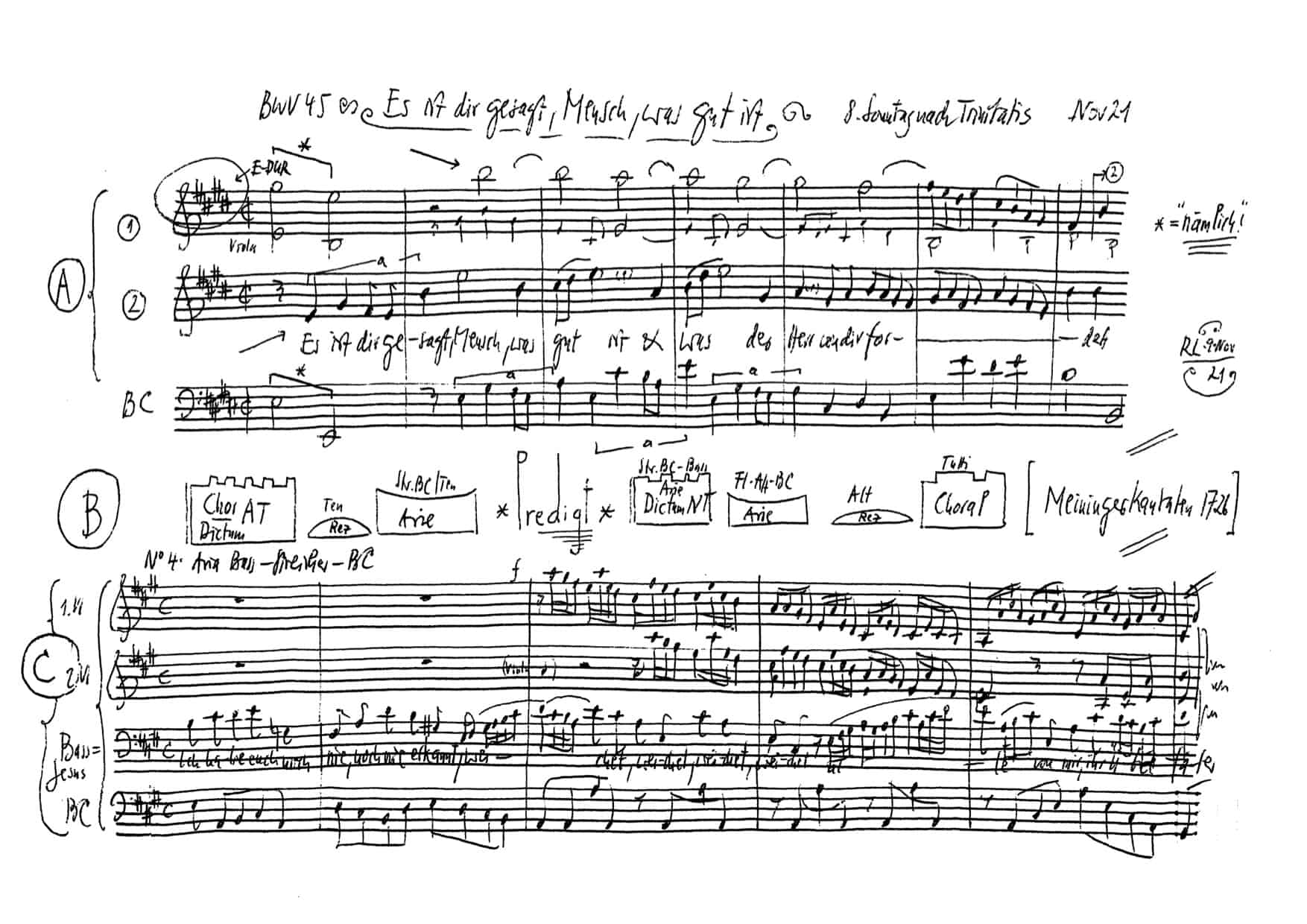

Es ist dir gesagt, Mensch, was gut ist

BWV 045 // For the Eight Sunday after Trinity

(It hath thee been told, Man, what is good) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute I+II, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Cornelia Fahrion, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Anna Walker, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Alexandra Rawohl, Simon Savoy

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Tobias Mäthger, Tiago Oliveira, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Sonoko Asabuki, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Transverse flute

Yoko Tsuruta, Tomoko Mukoyama

Oboe / Oboe d’amore

Philipp Wagner Laura Alvarado

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Sebastian Kleinschmidt

Recording & editing

Recording date

26/11/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

11 August 1726, Leipzig

Text

Micah 6:8 (movement 1); Matthew 7:22–23 (movement 4); Johann Heermann (movement 7); unknown source (movements 2, 3, 5, 6)

Libretto

1. Chor

«Es ist dir gesagt, Mensch, was gut ist und was der Herr von dir fordert, nämlich: Gottes Wort halten und Liebe üben und demütig sein vor deinem Gott.»

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Der Höchste läßt mich seinen Willen wissen

und was ihm wohlgefällt;

er hat sein Wort zur Richtschnur dargestellt,

wornach mein Fuß soll sein geflissen

allzeit einherzugehn

mit Furcht, mit Demut und mit Liebe

als Proben des Gehorsams, den ich übe,

um als ein treuer Knecht dereinsten zu bestehn.

3. Arie — Tenor

Weiß ich Gottes Rechte,

was ists, das mir helfen kann,

wenn er mir als seinem Knechte

fordert scharfe Rechnung an?

Seele! denke dich zu retten,

auf Gehorsam folget Lohn;

Qual und Hohn

drohet deinem Übertreten!

4. Arioso — Bass

«Es werden viele zu mir sagen an jenem Tage: Herr, Herr, Herr, haben wir nicht in deinem Namen geweissaget, haben wir nicht in deinem Namen Teufel ausgetrieben? haben wir nicht in deinem Namen viel Taten getan? Denn werde ich ihnen bekennen: Ich habe euch noch nie erkannt, weichet alle von mir, ihr Übeltäter!»

5. Arie — Alt

Wer Gott bekennt

aus wahrem Herzensgrund,

den will er auch bekennen.

Denn der muß ewig brennen,

der einzig mit dem Mund

ihn Herren nennt.

6. Rezitativ — Alt

So wird denn Herz und Mund selbst von mir Richter sein,

und Gott will mir den Lohn nach meinem Sinn erteilen:

Trifft nun mein Wandel nicht nach seinen Worten ein,

wer will hernach der Seelen Schaden heilen?

Was mach ich mir denn selber Hindernis?

Des Herren Wille muß geschehen,

doch ist sein Beistand auch gewiß,

daß er sein Werk durch mich mög wohl vollendet sehen.

7. Choral

Gib, daß ich tu mit Fleiß,

was mir zu tun gebühret,

worzu mich dein Befehl

in meinem Stande führet!

Gib, daß ichs tue bald,

zu der Zeit, da ich soll;

und wenn ichs tu, so gib,

daß es gerate wohl!

Sebastian Kleinschmidt

BACH IN THE GDR

Facets of a problem

“It is told thee, man, what is good” – could unintentionally also be the motto of what the Foundation asked me to speak about here today, namely Bach in the GDR. The GDR was a kind of educational dictatorship, a guardian state, which proclaimed without any reference to religion: “It is told you, man, what is good. And it was said by us, the new historical power. However, there was no mention of what is spoken of in today’s cantata text, not of “keeping God’s word”, of “practising love” and of “being humble”. Atheists could safely leave that aside. And that brings me to the subject.

According to its self-image, the GDR was a cultural state, and that from the very beginning. This meant that when it came to heritage, it was neither nihilistic nor a cultural revolutionary. Not that they did not have their own cultural will, but the socialist transformation of society was to proceed without ideological doggedness. As far as the traditional was not used as ammunition in the fight against the philosophical ambitions of the new state, people had a broad heart and liked to quote Goethe’s words: “What you have inherited from your fathers, acquire it in order to possess it”.

Bach’s music was in principle unchallenged. After all, not only Goethe, not only Hegel, but also Marx had adored him. All three admired the St Matthew Passion. Not a negative word about the baroque master was known even from Georg Lukács, the Lord Privy Seal of the communist cultural idea. And if that wasn’t enough for you, you could check with Ernst Bloch. He considered Bach to be one of the greatest of all, because he created “the most erudite and at the same time the most profoundly soulful music”. The author of The Principle of Hope explained what was meant by this by means of the ethos and affect content of Bach’s melodic-rhythmic figures. “Thus the figures of languor, pain, agony as well as pride, joy, vivid as well as transfigured, terror, jubilation. Bach’s unparalleled range of expression extends from fear of death and longing for death to consolation, confidence, peace and victory.”

Peter Schreier, the unforgettable tenor from Dresden, who became famous as the evangelist in Bach’s passions and oratorios, said after the turn of 1989: “Bach was not interpreted politically in the GDR. They tried to get him out of the church a bit, but otherwise treated everything as elsewhere.”

As elsewhere, presumably meant the performance practice. This did not apply in the same way to music research. The supreme purpose of Bach’s music is avowedly the praise of God. That alone was bound to become a problem in a worldview state like the GDR, with the “leading role of the working class and its Marxist-Leninist party” de facto existing from the beginning and later also constitutionally enshrined. And it became one.

Take the German Bach celebration in Leipzig from 23-26 July 1950. On the occasion of the 200th anniversary of his death, a large Bach conference was held in the music-filled city, with renowned scholars from both German states. It did not take long for controversy to erupt. One side, let us call it the vertical West German side, emphasised the divinity of Bach’s music; the other, the horizontal East German side, could not deny the reference to God, but wanted to relativise it. There was no question of Bach’s vocal works being tied to words and themes, but the religious content given in most cases could be interpreted either way, either theologically from within or non-theologically from without. It should be remembered that Marx and Engels saw themselves as decidedly hostile to theology and the church and did not have a considerable arsenal of elaborate concepts critical of religion at their disposal for nothing. Just think of the famous “religion is the opium of the people”.

The delicate point was also echoed in two speeches at the Bach national celebration a few days later. Wilhelm Pieck, the state president, said of the composer: “In his works not only the time-bound religious man suffers, triumphs and sings.” He went on to say, “Bach’s revolutionary deed was that he freed music from the shackles of medieval scholasticism and broke old ties.” It was Bach “who first gave music the deep human content that connects it with the whole people. That is why folk music, folk song and folk dance play such a large role in Bach’s work (…) This humanistic progressive content of Bach’s work has been deliberately concealed or suppressed until now.” Pieck did not mean the Third Reich, he meant West Germany.

We see, not a word about Christianity, not a word about Luther, not a word about piety. The religious was made to disappear, as it were, in the humane. This, by the way, was the method of Feuerbach, on whom Marx based himself. By replacing theology with anthropology in his interpretation of Christianity, Ludwig Feuerbach dissolved the superworld into thin air and made religious faith simply irrelevant.

After Wilhelm Pieck, the composer Ernst Hermann Meyer spoke. He said: “Despite intensive and fruitful scholarly research by men like Spitta, Schweitzer and others, the interpretation of Bach has suffered above all from the fact that numerous theorists sought to explain the great composer as a human being whose spirit was at home only in the beyond; they tried to make his work into a haven of mysticism and escapism”.

This marked the front line. It was the same as the one during the musicological conference a few days earlier. The Freiburg researcher Wilibald Gurlitt had given the keynote lecture. As far as the religious in Bach was concerned, he said: “Johann Sebastian Bach’s basic religious experience of music and music-making is (…) not a private matter for the composer, but one that is binding for his creative work and his oeuvre. It directs one’s gaze from sensuous phenomena to the last things. That readiness to go to the grave and to heaven, that evening and dying mood, as it spreads out in the sounds of Bach’s cantatas and passions, motets and hymns, has nothing to do with an escape from the world and existence, nothing to do with modern weltschmerz or nihilism. Rather, it is rooted in the faithful and confident knowledge of the Christian truth and reality of a fatherly divine hand that omnipresently intervenes in our lives to bring order”.

When it came to the discussion, Georg Knepler, Ernst Hermann Meyer and Harry Goldschmidt countered more or less vehemently. Goldschmidt said: “What amazed me most about Gurlitt’s lecture was the theological emphasis of his approach. Bach is said to have conceived his complete works from a basic theological feeling. No one will deny that Bach was a pious and Bible-loving man. However, Chubow (a Soviet music historian – S.K.) has shown that religiosity was an expression of social need. He referred to Engels, according to whom the social conflicts of that time could not take place in any other way than in Christian garb. (…) We must therefore understand Bach’s religiosity in social terms.”

From there it was not far to Knepler, who not only put his legitimate atheistic ambition into proving that one had neither biographical nor musical right to “reserve Bach exclusively for the church”, but in the debate flatly declared: “The starting point for research into any world view, including that of Bach and his contemporaries, is offered by the works of Marx and Engels. (…) The key to a correct assessment of Bach is offered only by social science.”

There it is again, the forced anti-theological tendency of those who saw themselves as campaigners for a new, more worldly image of Bach. Every revolution lives from the anti-religious zeal of its followers. And the GDR, occupied by the Red Army, had emerged from a revolution, albeit a Soviet-commanded one. Bertolt Brecht said, better a commanded revolution than none at all. But the other side did not capitulate. The Hessian theologian and Bach researcher Walter Blankenburg declared in the discussion: “The first demand is surely that we owe it to Bach to take his Jesu Juva and Soli Deo Gloria seriously. If we don’t, we face the question of whether we take Bach seriously at all.”

We see how strong the missionary rivalry was between Christians and Marxists at that time. One knows about their faith, the other believes in their knowledge. As if they were spiritual competitors, antagonists of the proclamation. Kingdom of God and Holy Spirit on one side, communism and true social science on the other.

If the secular faction had listened to Bloch, the dispute would not have turned out so sharply. Already in his first work, the 1918 Spirit of Utopia, he spoke of Bach’s “expressive baroque”, which meant “baroque in the abrupt peripety, baroque above all in the agitated Christian emotional content”. In Bach’s music, a “spiritual I” becomes representational, in contrast to Mozart’s “secular I”. “As Mozart in a moving way, light, free, buoyant, loosened and brilliant made the feelings sound, so Bach in a more measured way, heavy, insistent, bound, hard rhythmising, lacklustre shows deeply the I and its emotional inventory.”

The passage reminds me of a phrase by the philosopher Isaiah Berlin: “If the angels play for God, they play Bach; for each other they play Mozart.”

Bloch had no need to speak of ‘religious garb’, of ‘religious envelopment” in the case of Bach, which is then well unveiled in Enlightenment terms as this-world humanism. Bloch said: “It is the enclosure of the Christian will to do, illuminated from within, in the sense that Bach’s music expresses the struggle for the salvation of the soul…”

The phrase also fits today’s cantata. “Soul! Think to save yourself,” it says in the tenor aria. And the alto voice in the recitative admonishes those who do not keep God’s word: “Who will hereafter heal the harm of souls?”

The early Bloch was not known to the Marxists of the time. Geist der Utopie never appeared in the GDR. Whether the book would have fitted into the atheistic theocracy of the young GDR is doubtful. One only has to think of the chapter called “Karl Marx, Death and the Apocalypse”.

Apocalypse should not be the last word on the subject of Bach in the GDR, although many a party supporter of the first socialist state on German soil must have felt its demise to be apocalyptic. Could Bach have given him consolation? Bach’s poignant cantabile melodic language? Bach, the cathedral builder of high and low sound? The answer I would like to give could have led to rapprochement in the Leipzig controversy of that time, given good will, namely: it does not take Christian confession to experience that Bach’s music is a realm of grace.

“Where are we when we listen to music?”, Peter Sloterdijk once asked. He didn’t mean in the concert hall or in church. He meant where we are spiritually. In the context of Bach, I am inclined to say: in heaven – with thoughts of the earth. On earth – with thoughts of heaven. In eternity – with thoughts of the now. In the now – with thoughts of eternity. In God’s breast – with thoughts of the people. In the breast of man – with thoughts of God.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).