Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden

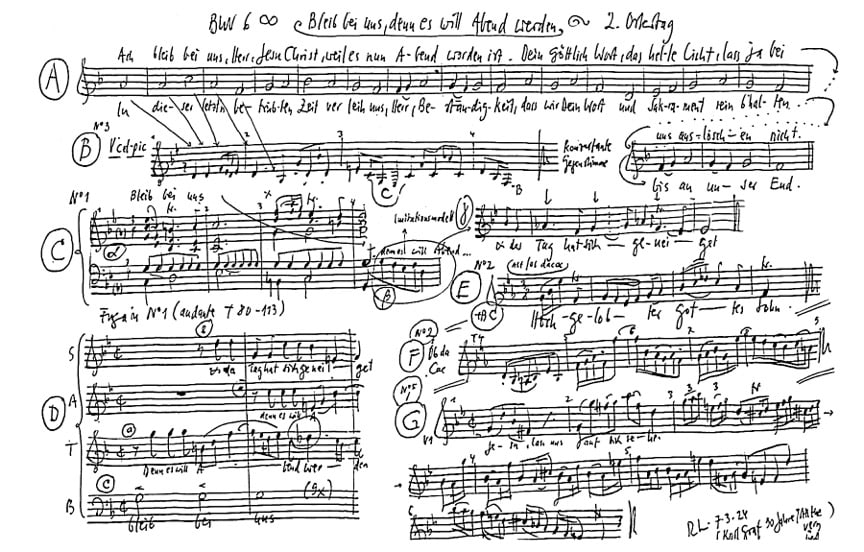

BWV 006 // For the Second Day of Easter

(Bide with us, for it will soon be evening) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Laura Kull, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Jan Thomer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Joël Morand, Klemens Mölkner

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Johannes Hill, Philippe Rayot, Julian Redlin, Jonathan Sells

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Salome Zimmermann, Elisabeth Kohler, Monika Baer, Andrea Brunner, Patricia Do

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Claire Foltzer

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Thomas Meraner

Oboe da caccia

Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speakers

Hans-Jürg Stefan, Klaus Bäumlin

Recording & editing

Recording date

22/003/2024

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

2 April 1725, Leipzig

Text sources

Christoph Birkmann; Luke 24:29 (movement 1); Nikolaus Selnecker, with verse 1: Philipp Melanchthon, verse 2: Nikolaus Selnecker (movement 3); Martin Luther (movement 6)

In-depth analysis

The Gospel of the Road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13-35), a standard reading for the Second Day of Easter, is a story of striking ambivalence. Indeed, how the disciples’ grief and confusion after Jesus’ crucifixion transforms into curiosity and confidence through conversation with their remarkably well-informed fellow traveller, and how the events of the day culminate in a nigh unimaginable appearance of the risen Christ is a narrative that retains its power to touch and inspire today, just as it did in Bach’s time.

The opening chorus of the cantata “Bleib bei uns” (Bide with us, BWV 6) is initially dominated by dark and fearful tones. In this sombre C-minor setting, the tremolo strings and plaintive oboe figures descending into the lowest register evoke not merely impending nightfall in the countryside, but the shadow cast by the Passion and the abject despair of those left behind after the death of their teacher. Far from being a cheerful invitation, the words “Bleib bei uns” are a cry for help from the depths of the soul: “Do not leave us, not yet”. The glimmers of hope that increasingly emerge from behind the descending figures, and the pleading entreaties that take on characteristics of an affirmation of faith lend Bach’s setting its persuasiveness, as does the separation between day and night as an expression of the outer earthly world and faithful perseverance – the latter motif taking shape in the interposed double fugue. A dramatic unison call, more reminiscent of Mendelssohn and Brahms than Leipzig in 1725, then leads to an abbreviated repetition of the opening section, which addresses the listener directly and eschews a comforting postlude.

After such density of music and emotion, the airy texture of the following alto aria proves especially soothing. Over pizzicato bass notes in a warm E-flat major, an upper register instrument begins to sing; its distinctive timbre was apparently so dear to Bach that he was loath to choose between the oboe da caccia and viola in the cantata’s documented re-performances. This tender prayer already anticipates the later recognition of the “hochgelobter Gottessohn” (highexalted Son of God) and thus the culminating event of the Emmaus narrative, transforming the disciples’ plea that Jesus remain into a longing for his everlasting presence in the darkness of the world.

Surprisingly, Bach and his librettist Birkmann proceed not with a recitative, but a structurally similar movement that, as a double chorale verse, nonetheless opens up new horizons. Once again, it is a solo instrument in the sonorous middle register – a violoncello piccolo – that underscores the intensity of the soprano’s entreaty with virtuoso cantilenas and broken chords. Bach later included this rewarding trio setting of the congregational Evensong in his collection of Schübler Chorales, published in 1747/48, all of which were based on such cantata settings. Although the first verse is based on a hymn translation by the peaceable Philipp Melanchthon, the fact that this chorale, first printed in 1611, was written by the Leipzig superintendent and bitter anti-Calvinist Nikolaus Selnecker, speaks of the conflictridden history of the Lutheran Reformation, which was also beset by infighting.

Despite such beatific music, the darkness has by no means lifted, hence the combination of lament and critical self-reflection in the bass recitative. Here, as described in the Apocalypse of John, God has “overturned the lampstands” mainly because humankind had spurned its Christian duty to honour his word and righteousness.

The tenor aria addresses this with the prayer “Jesu, laß uns auf dich sehen” (Jesus, keep our sights upon thee), which is lent the appropriate gravitas by a probing string accompaniment in an unforgiving G-minor key. Here, the cascading triplet figures assigned to the first violins come across as admonitory biblical warnings punctuating a sermon on repentance. That this aria forgoes a da capo section and comes to a surprisingly quick end hints at the urgency of the matter – this unique bright light must never extinguish.

If, in keeping with Protestant tradition, the light of faith is understood as the word of Christ, it is hard to imagine a more fitting end to the cantata than the second verse of Luther’s late chorale “Erhalt uns Herr bei deinem Wort” (Maintain us, Lord, within thy word). It depicts a Christendom still reeling from the fear of abandonment, one that asks for tangible, living support in the face of an Emmaus constellation that remains terrifyingly persistent.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden, und der Tag hat sich geneiget.»

2. Arie — Alt

Hochgelobter Gottessohn,

laß es dir nicht sein entgegen,

daß wir itzt vor deinem Thron

eine Bitte niederlegen:

Bleib, ach bleibe unser Licht,

weil die Finsternis einbricht.

3. Choral — Sopran

Ach bleib bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ,

weil es nun Abend worden ist,

dein göttlich Wort, das helle Licht,

laß ja bei uns auslöschen nicht.

In dieser letzt’n betrübten Zeit

verleih uns, Herr, Beständigkeit,

daß wir dein Wort und Sacrament

rein b’halten bis an unser End.

4. Rezitativ — Bass

Es hat die Dunkelheit

an vielen Orten überhand genommen.

Woher ist aber dieses kommen?

Bloß daher, weil sowohl die Kleinen als die Großen

nicht in Gerechtigkeit

vor dir, o Gott, gewandelt

und wider ihre Christenpflicht gehandelt.

Drum hast du auch den Leuchter umgestoßen.

5. Arie — Tenor

Jesu, laß uns auf dich sehen,

daß wir nicht

auf den Sündenwegen gehen.

Laß das Licht

deines Worts uns helle scheinen

und dich jederzeit treu meinen.

6. Choral

Beweis dein Macht, Herr Jesu Christ,

der du Herr aller Herren bist;

beschirm dein arme Christenheit,

daß sie dich lob’ in Ewigkeit.

Klaus Bäumlin & Hans-Jürg Stefan in dialog

Klaus Bäumlin:

Dear Bach congregation, before you stand two old men, friends since our student days, connected by singing and making music together. When we agreed to reflect together on the Bach cantata “Abide with us…”, we made this promise with the proviso of the Letter of James: “You do not know what tomorrow will bring, what your life will be like … You should say: If God wills and we live, we will do this and that” (James 4:15).

Two old men, afflicted with all kinds of age-related ailments. For example, I can no longer sing. Dear singers, you can hardly imagine what it’s like when someone for whom singing has been a fundamental element of life since childhood can no longer sing. And you, Hans-Jürg, had to give up your string quartet playing, which you had nurtured for over 70 years, last year due to the late effects of a fall down the stairs. Two old men in the evening of life.

Our cantata is an Easter cantata. However, Easter is not its theme, nor is there an Easter chorale. Instead, the cantata focuses on the disciples’ request to Jesus: “Stay with us, for it is getting dark. What is a simple indication of the time of day in Luke’s story is now interpreted and expanded metaphorically. The simple indication of the time in the story – evening is coming – becomes a general existential statement that concerns every human being.

And so the disciples’ request could expand into a prayer written by Georg Christian Diffenbach in 1853:

Bleibe bei uns, denn es will Abend werden,

und der Tag hat sich geneigt.

Bleibe bei uns und bei deiner ganzen Kirche.

Bleibe bei uns am Abend des Tages,

am Abend des Lebens,

am Abend der Welt.

Bleibe bei uns, wenn über uns kommt

die Nacht der Trübsal und Angst,

die Nacht des Zweifels und der Anfechtung,

die Nacht des bitteren Todes.

Bleibe bei uns und allen deinen Gläubigen

in Zeit und Ewigkeit. (RG 586)

With this expansion, the simple word “evening” is charged with human experiences and emotions, with gloom and fear, with doubt and temptation, with dying and death, even with the end of the world. This prayer of supplication found its place in the liturgy of many evening prayers. The friendly word “evening” becomes cryptic, suddenly becomes a threat and a question. Sleep, the brother of death.

The keyword “evening” is also the theme of our reflection. We are both in the evening of life.

We may all be standing at the end of the world. Bleib bei uns …

Hans-Jürg Stefan:

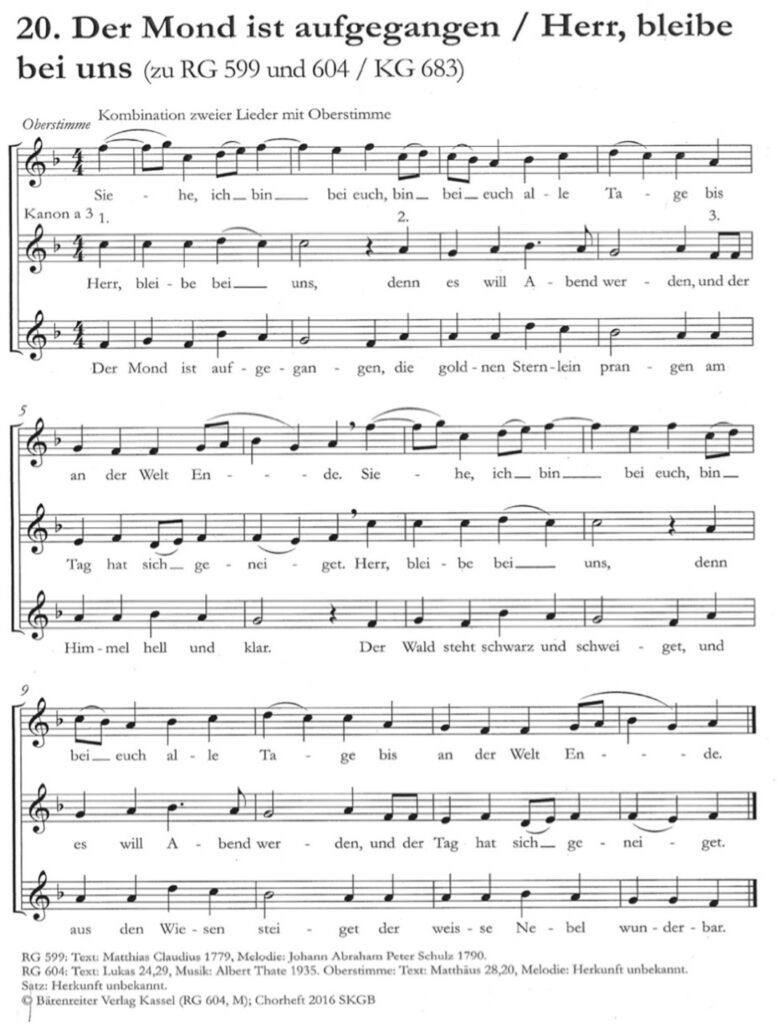

Herr, bleibe bei uns, denn es will Abend werden we have been singing from the new youth hymnal “Mein Lied” on the evenings of the Young Church since 1953. Since 1962, this canon and Der Mond ist aufgegangen (The moon has risen) have been familiar evening songs in our family, which we used to accompany our four children to sleep. Over the decades, these songs proved to be the “basic nourishment of our trust”. These were later joined by larger musical works in singing weeks and choirs, such as Josef Rheinberger’s six-part “Abendlied” Bleib bei uns, denn es will Abend werden (op. 69, 3) – and even the preparation of our Bach cantata during the Easter singing week 2002 at Leuenberg/BL (conductor: Gothart Stier).

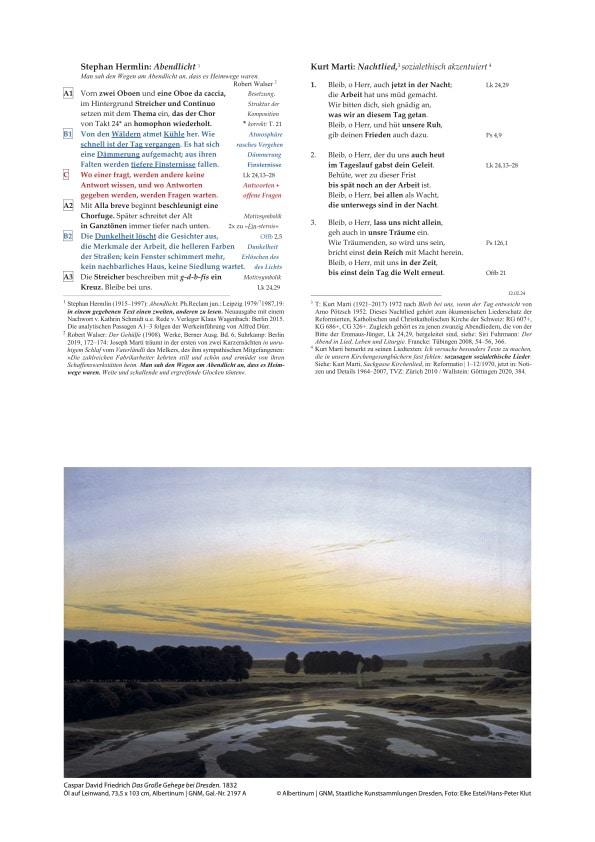

In 1987, on the occasion of a conference of the hymnbook commissioners of the Protestant Churches East & West in the Bonhoeffer House in Berlin Mitte, I discovered the impressive literary depiction of an evening music with our cantata, in: Stephan Hermlin: Abendlicht (19877 ). Even the book cover appears to be charged with a special aura through the reproduction of a German Romantic painting:

Öl auf Leinwand, 73,5 x 103 cm, Albertinum | GNM, Gal.-Nr. 2197 A

© Albertinum GNM, Staatl. Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Foto: Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut

The artist Caspar David Friedrich (1832) conceived the painting, like many other works, with “romantic calculation” (Werner Busch, 2024): Even at first glance, two opposing arched forms (hyperbolas) pointing beyond each other catch the eye: The lower one, bordering the Elbe, encompasses gloomy alluvial land with pools of water. Above it are dark groups of trees. Opposite this earthly area, marked by a gray-blue band of clouds, appears the “arch open to eternity”, as it were, high above the dark forest areas. The evening light shines through torn wisps of cloud in a magnificent range of colors. – Inside the book, the motto from which the book’s title is taken follows on the first flyleaf: Man sah den Wegen am Abendlicht an, dass es Heimwege waren (Robert Walser).[1] Hermlin’s description of Easter evening music with our cantata follows on the second flyleaf:

In the sections printed in black, Hermlin follows the commentary by Alfred Dürr (Kassel, 1971). In between, he describes the atmosphere in which the singing and music are performed. This is how he himself read from a young age, in that [quote] “depicted people and actions were not so important to me, but rather an imagined landscape, a time of day, an aura in which people moved and performed their actions. The tendency to place the atmospheric above what was actually reported or, as one could also say, to read a second text in a given text was supported …”[2] This happens along the keywords: Forests – coolness – quickly passed – twilight – deeper darkness – darkness – lights out.

This downward spiral is frightening. It corresponds to the descent of the libretto to the low point in the bass recitative, an intensified quotation from the Book of Revelation (Acts 2:5): There, God threatens the church of Ephesus to overturn the lampstand. In the cantata, the threat has already been carried out: Therefore you have also knocked down the lampstand!

At the center of his collage, Hermlin captures the disciples’ conversation in a single sentence. While they visualize what had happened to Jesus during the past three days in Jerusalem, the stranger enlightens them on the basis of prophetic scriptures. Nevertheless, they do not yet recognize in him the resurrected one: where one asks, others will not know the answer, and where answers are given, questions will be waiting.

Dear Bach congregation, Hermlin’s description of a performance of our cantata ends with the first three words of the opening chorus: Bleib bei uns! The same source (Lk. 24, 29) is the source of the canon already mentioned: Herr, bleibe bei uns, denn es will Abend werden, und der Tag hat sich geneiget.

First we all sing together in unison. Then the female voices develop the canon to three voices:

1st on the podium,

2nd in the nave on the right,

3rd in the nave on the left.

On the 4th cue, the men join in with the 1st verse of Der Mond ist aufgegangen:

Klaus Bäumlin:

Der Mond ist aufgegangen by Matthias Claudius is my favorite evening song. As one of the very few songs in our hymnal, perhaps the only one, it belongs to the great poetry of world literature. As a child, I used to sing it with my mother before going to sleep. Decades later, I understood that this song does not describe an idyll, that it is not all harmony. There is a foreboding, a sense of sinister abysses and contradictions. It begins quite peacefully: the moon has risen, the golden stars shine bright and clear in the sky. Peace and tranquillity, you might think.

Then it suddenly becomes eerie: the forest is black and silent. White mist rises from the meadows, wonderful, but also somewhat ghostly. What if it reached the sky and obscured the light of the moon and the stars? A shiver comes over you, a slight chill – the evening breeze is cold. A breath of transience wafts over you. We proud children of men are vain poor sinners and don’t know much at all. We spin webs of air and seek many arts and get further from the goal. Losing sight of the goal, not finding the way in the thick fog, getting lost and lost in the black forest, in the dark, in the cold. Nightmares from early childhood emerge. We could be punished. The consequences of our proud arts could drag us into the abyss. And next door, in the quiet room, the sick neighbor sleeps. Will he still see the morning sun? In the moonlight, the world becomes a silent chamber for one night, where you can sleep off the day’s misery and forget it – if we can find sleep. But in the morning, the day’s misery is back, with all its abysses and contradictions, and the world is again full of the noise and misery of humanity. And the silent chamber, does it not also remind us of the last chamber in which we will one day lie and forget everything and fall asleep?

But isn’t there another way to talk and sing about evening and night? As Matthias Claudius wrote: “The golden stars shine bright and clear in the sky; the moon is only half visible, yet it is round and beautiful. There are some things that we can safely laugh at because our eyes cannot see them.

Death can also be gentle and sleep calm and peaceful:

Guten Abend, gut Nacht, / mit Rosen bedacht, /

mit Näglein besteckt, / schlupf unter die Deck: /

/: Morgen früh, wenn Gott will, wirst du wieder geweckt. ://

Guten Abend, gut Nacht, / von Englein bewacht, /

die zeigen im Traum / Christkindeleins Baum: /

Schlaf nun selig und süss, schau im Traum’s Paradies.

There are not only nightmares, but also angelic dreams, dreams of happiness and peace, dreams that visualize beautiful memories and anticipate a bright future.

Hans-Jürg Stefan:

We also encounter dreams and hopeful expectations in Kurt Marti’s Nachtlied Bleib, o Herr, auch jetzt in der Nacht. The poet names the addressee of the night prayer, Christ, twice per verse with the New Testament title: “Lord” (Kyrios).

Marti describes his contributions to the hymnal as “socio-ethical songs” (Notes & Details, 384) – he is concerned with vital social issues: With verse 1, we ask that Christ, like the disciples of Emmaus back then, may also accompany us through the night:

Bleib, o Herr, auch jetzt in der Nacht;

die Arbeit hat uns müd gemacht.

Wir bitten dich, sieh gnädig an,

was wir an diesem Tag getan.

Bleib, o Herr, und hüt unsere Ruh,

gib deinen Frieden auch dazu.

We entrust him with the burdens of our day’s work and everything that remains pending; we also entrust him with our night’s rest and our hope for healing peace.

In verse 2 we pray for those people who work for others at night and for those who are out late:

Bleib, o Herr, der du uns auch heut

im Tageslauf gabst dein Geleit.

Behüte, wer zu dieser Frist

bis spät noch an der Arbeit ist.

Bleib, o Herr, bei allen als Wacht,

die unterwegs sind in der Nacht.

Verse 3 takes up the forward-looking perspective of Psalm 126, asking for the presence of Christ even in our dreams. Here the night song becomes a song of the kingdom of God:

Bleib, o Herr, lass uns nicht allein,

geh auch in unsre Träume ein.

Wie Träumenden, so wird uns sein,

bricht einst dein Reich mit Macht herein.

Bleib, o Herr, mit uns in der Zeit,

bis einst dein Tag die Welt erneut.

Klaus Bäumlin:

We return to the beginning of our cantata with this night song composed from the Emmaus disciples’ request.

In its middle, in No. 3, the soprano voice sings the chorale

Ach bleib bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ.

We conclude our reflection with him:

Ach bleib bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ,

weil es nun Abend worden ist,

dein göttlich Wort, das helle Licht,

lass ja bei uns auslöschen nicht.

Hans-Jürg Stefan:

Bleib, o Herr, lass uns nicht allein,

geh auch in unsre Träume ein …

[1] Robert Walser: Der Gehülfe (1908). Werke, Berner Ausgabe, vol. 6, Suhrkamp: Berlin 2019, 172-174. On the first of two nights in the carcass, Joseph Marti dreams in a restless sleep of the fatherland of the milker, his sympathetic fellow prisoner: “The numerous factory workers returned home from their workshops, quiet and beautiful and tired. You could see from the evening light that they were going home. Wide and resounding and poignant bells rang out.”

[2] Stephan Hermlin (1915-1997): Abendlicht. Ph. Reclam jun.: Leipzig 1979/7 1987, 19th new edition, without reproduction of the painting by C. D. Friedrich, with an afterword by Kathrin Schmidt and a speech by publisher Klaus Wagenbach: Berlin 2015.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).