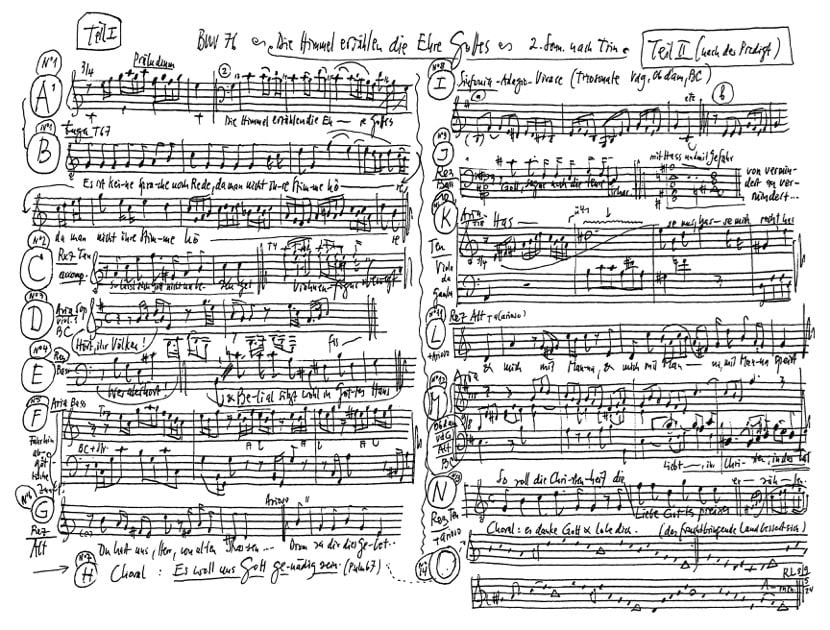

Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes

BWV 076 // For the Second Sunday after Trinity

(The heavens are telling of God the glory) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass; vocal ensemble, trumpet, oboe I+II, viola da gamba, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Cornelia Fahrion, Gabriela Glaus, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Susanne Seitter, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Antonia Frey, Laura Kull, Francisca Näf, Lea Scherer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Manuel Gerber, Joël Morand, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Serafin Heusser, Israel Martins, Daniel Pérez, Julian Redlin

Orchestra

Conductors

Renate Steinmann, Lea Scherer (Rudolf Lutz was absent due to illness)

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Lisa Herzog-Kuhnert, Salome Zimmermann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Claire Foltzer

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Viola da Gamba

Martin Zeller

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Katharina Arfken

Oboe da caccia

Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Jaroslav Rouček

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Daniel Johannsen, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Carolin Emcke

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/05/2024

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

6 June 1723 – Leipzig

Text sources

Unknown poet; 1: Psalm 19:2 and 4; 7 and 14: Martin Luther 1524

Libretto

Erster Teil

1. Chor

«Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes, und die Feste verkündiget seiner Hände Werk. Es ist keine Sprache noch Rede, da man nicht ihre Stimme höre.»

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

So läßt sich Gott nicht unbezeuget!

Natur und Gnade redt alle Menschen an:

Dies alles hat ja Gott getan,

daß sich die Himmel regen

und Geist und Körper sich bewegen.

Gott selbst hat sich zu euch geneiget

und ruft durch Boten ohne Zahl:

Auf! kommt zu meinem Liebesmahl!

3. Arie — Sopran

Hört, ihr Völker, Gottes Stimme,

eilt zu seinem Gnadenthron!

Aller Dinge Grund und Ende

ist sein eingeborner Sohn,

daß sich alles zu ihm wende.

4. Rezitativ — Bass

Wer aber hört,

da sich der größte Haufen

zu andern Göttern kehrt?

Der ältste Götze eigner Lust

beherrscht der Menschen Brust.

Die Weisen brüten Torheit aus,

und Belial sitzt wohl in Gottes Haus,

weil auch die Christen selbst von Christo laufen.

5. Arie — Bass

Fahr hin, abgöttische Zunft!

Sollt sich die Welt gleich verkehren,

will ich doch Christum verehren,

er ist das Licht der Vernunft.

6. Rezitativ — Alt

Du hast uns, Herr, von allen Straßen

zu dir geruft,

als wir im Finsternis der Heiden saßen,

und, wie das Licht die Luft

belebet und erquickt,

uns auch erleuchtet und belebet,

ja mit dir selbst gespeiset und getränket

und deinen Geist geschenket,

der stets in unserm Geiste schwebet.

Drum sei dir dies Gebet demütigst zugeschickt:

7. Choral

Es woll uns Gott genädig sein

und seinen Segen geben;

sein Antlitz uns mit hellem Schein

erleucht zum ewgen Leben,

daß wir erkennen seine Werk

und was ihm lieb auf Erden,

und Jesus Christus Heil und Stärk

bekannt den Heiden werden

und sie zu Gott bekehren.

Zweiter Teil

8. Sinfonia

9. Rezitativ — Bass

Gott segne noch die treue Schar,

damit sie seine Ehre

durch Glauben, Liebe, Heiligkeit

erweise und vermehre.

Sie ist der Himmel auf der Erden

und muß durch steten Streit

mit Haß und mit Gefahr

in dieser Welt gereinigt werden.

10. Arie — Tenor

Hasse nur, hasse mich recht,

feindlichs Geschlecht!

Christum gläubig zu umfassen,

will ich alle Freude lassen.

11. Rezitativ — Alt

Ich fühle schon im Geist,

wie Christus mir

der Liebe Süßigkeit erweist

und mich mit Manna speist,

damit sich unter uns allhier

die brüderliche Treue

stets stärke und erneue.

12. Arie – Alt

Liebt, ihr Christen, in der Tat!

Jesus stirbet für die Brüder,

und sie sterben für sich wieder,

weil er sich verbunden hat.

13. Rezitativ — Tenor

So soll die Christenheit

die Liebe Gottes preisen

und sie an sich erweisen:

bis in die Ewigkeit

die Himmel frommer Seelen

Gott und sein Lob erzählen.

14. Choral

Es danke, Gott, und lobe dich

das Volk in guten Taten;

das Land bringt Frucht und bessert sich,

dein Wort ist wohlgeraten.

Uns segne Vater und der Sohn,

uns segne Gott, der Heilge Geist,

dem alle Welt die Ehre tu,

für ihm sich fürchte allermeist

und sprech von Herzen: Amen!

Carolin Emcke

When I received the enquiry, I accepted before I had finished reading the email.

What better task could there be than to talk about Bach and one of the cantatas.

I thought.

But the task is full of pitfalls and more difficult than I had hoped, especially in terms of the time frame.

To be honest, if I could have chosen a cantata, it wouldn‘t have been this one.

The closest one to me is “Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen”, BWV 56, which I’m only mentioning here in case you wanted to invite me back.

But I also know why I was given this job.

It is the verses that we will hear in the following part that address “hatred” as a theme. Sentences 9 and 10, and so I will focus on these two sentences in my reflections today.

9th recitative

God bless the faithful flock,

That they may honour his glory

Through faith, love and holiness

Prove and increase.

She is heaven on earth

And must through constant strife

With hatred and with danger

Be purified in this world.

10th aria

Hate me, hate me right,

Hostile generation!

To embrace Christ in faith,

I will leave all joy.

I would like to talk very briefly about the music itself (1) and then about the motif of hatred. In other words, what hate does, what hate causes. Not where it comes from, not how it is justified. There is often a desperate search for rationality, for an explanation, instead of recognising hatred as unfounded or unfoundable. And it would leave in the shadows those whom it seeks as its object. I have always tried to avoid this, especially in these times of hatred and resentment. I am preoccupied with how it works, how it disrupts. All of them. Those whom he seeks out as objects, but also those who are permeated by him. (2)

And finally, I return to the lines of the cantata and would like to quietly contradict them. (3)

*

(1)

Musically (not lyrically), the aria is particularly relevant.

Just hate, hate me right,

Enemy sex!

To embrace Christ in faith,

I will leave all joy.

It is a da capo aria. Textually divided into two sections, “Hate only, hate me rightly, hostile sex“, the A part, is repeated after the B part, “Christum believing to embrace, I will leave all joy“. The hatred thus frames. The believer is surrounded, hemmed in by the enemy.

The “hasse” appears 16 times in the A section alone.

The repetition of the “hate” element tells us how powerful, how dominant the hate is, how threatening. Being hated by enemies, as the music tells us, is not a solitary, isolated experience; the “loyal band” is surrounded by the enemy sex. It is not something situational, but a constant in the lives of those who have dedicated themselves to the Lord.

The counter-image “Christum gläubig zu umfassen” again contains the two s-consonants that are already contained in the Hass, but here they are meant to proclaim a different message: The reconciling, believing devotion to Christ is expressed in an extended sequence of the chant on the syllable “fa”. The melisma, i.e. the long sequence of notes, the melodic line on a single syllable, the melisma of “um-faaaaaaaa-ssens” does musically what it sings about, it embraces Christ with a broad movement.

The hate is short-breathed and repetitive, whereas the faith is long-suffering and calming. The music makes the gesture itself in “umfassen”, as a contrast to the abrupt, halting “Hass”. The key also changes here from major to minor, like a transformation into a warmer one.

(2)

“Hate only, hate me rightly” is the response of those in the cantata who are not intimidated, who know that as believers they will be “purified” as a community in this world “through constant strife, with hatred and with danger”.

What is this idea of the Christian community that it would be “purified” through strife, hatred and danger? What reference is there to this? I am not theologically educated and the “reflection” should, so I was told, rather lead away and think in present references. But I first want to locate the words where they come from, in the biblical context, and then think about hatred from there.

Hate appears less frequently in the Bible as a term than might be assumed. But too often to address all references and uses here. And of course there are figures who hate, there are stories that illustrate hatred and anger, aversion and contempt in ever-changing transformations in images and stories.

The word itself covers a broad spectrum of meanings, hatred as contempt and enmity, but also as aversion, as a rather banal dislike, hatred as raging anger, as a never-ending force that wants to destroy the opponent – this exists above all in Amalek, the Amalekites, the eternal enemy, of whom we are told centrally in Exodus, in the 2nd book of Moses, and who appears again and again because it is generations that are persecuted, whose names are to be erased, who are to be destroyed. He appears again and again because it is generations that, according to divine law (or the curse), are to be persecuted, whose names are to be erased, who are to be destroyed. Amalek as a symbolic figure, as an emblem of the arch-enemy, reaches (unfortunately) into the present.

Hate is multifaceted, ambiguous, not always referring to this hot, all-consuming affect. Sometimes it also appears harmless and cheerful.

My favourite part is certainly the one in Proverbs:

It is better a dish of herbs with love than a fattened ox with hatred. (Proverbs 15, 17)

But the idea from our cantata that hatred and hostility are at the core of the experience of faith, that religious faithfulness is shown and proven in the face of challenge, is a recurring biblical motif.

Sometimes it comes as a warning, in which the Lord tells those who believe in him about what threatens them.

Do not be surprised, my brothers, if the world hates you! (1 John 3:23)

Sometimes it simply comes across as an assumption, as if the hatred of others is intrinsically linked to one’s own beliefs. As if hatred from the outside is the twin of inner conviction, as if no one can believe without being rejected for it:

And must be hated by everyone for my name’s sake. But whoever perseveres to the end will be saved. (Matthew 10:22)

And “must” be hated by everyone “for my name’s sake”.

What kind of faith is it that harbours the certainty of being rejected? What kind of community is it for which hatred is a necessary and purifying condition?

That is what the lines in the cantata claim.

What kind of hatred is this?

So what does hate do?

If I pull it away from the biblical references, the motive, and discuss it in more contemporary, political, psychological terms, how does hate work? Is it really something that a community, a group, what people who feel connected by the way they believe, the way they look, the way they live, the way they grieve, should desire? Is it really something that should be factored in, planned for? As a purifying factor? As a unifying element?

What Bach tells us musically about hatred in this cantata is true.

The repetitive, the unstoppable, that is a characteristic of hate.

Hatred captivates those who feel it. Hate is characterised by depth and centrality. Unlike displeasure or anger, hatred is not situational, not just partial. I can be angry with a person or a group with whom I otherwise remain close. I can find a person or a group unpleasant or harmful, I can want to belittle or ridicule them, and it passes again.

But hatred, as the philosopher Aurel Kolnai wrote, “presupposes the full realisation of the object”. In the object of hatred, the hater sees a “kind of decision, the fate of the world”.

Hatred is always about everything, categorically. In this respect, hatred is obsessively connected to the object of hatred, never letting up, repeating itself, as in the aria of the cantata.

Again and again: “hate me”.

Hatred is similar to resentment, both affects or references to the world that hang themselves up, that feed on themselves, that don’t get enough.

The French psychoanalyst Cynthia Fleury writes in her fantastic essay on resentment “Here lies bitterness buried”:

“Resentment is that which no longer knows how to make experiences.”

This also applies to hatred. Those who hate no longer have experiences.Those who hate no longer look, no longer listen. Those who hate remain locked in this fixation on the object that is presumably dangerous, presumably threatening, presumably existentially different, presumably perverse or animalistic or sick or corrosive or oppressive or impure. Hatred allows no contradiction, hatred takes up all space, all time, so that no impressions, no sensations, no experiences are permitted that could dissuade the hater from his deep, central, all-consuming feeling. In this way, hatred feeds on itself, a perpetual motion machine that does not want to have other, opposing experiences.

Hatred also deforms and disfigures those who feel it. Hatred is never only instrumentally directed at its victims; hatred also justifies the haters themselves.

It deprives them of thinking in other possibilities, of thinking in other scopes of action, everything is channelled, everything is focused on the object of hatred.

It scares me, the hatred, even from a distance, but even if I only recognise the inkling of this feeling in myself. Because of course I know it too. But I don’t want to be deformed, I don’t want to be stuck in this loop where I can no longer think or doubt. I shy away from this kind of certainty that goes hand in hand with hatred.

What does hatred do to those who fall victim to it? What does it do to people, individually or as members of a community, when they are hated by others? When they become the object of words, sentences, images, laws, rules, gestures, deeds, when they feel the hatred on their skin, their body? What does that do to someone who feels negated, rejected, despised, made invisible, hated?

These are already gradations in the vocabulary here. Not being seen is different from being hated. There are differences that count. Whether someone is disregarded or mistreated, whether there is verbal hostility or physical assault, that is something else. They are not all equally violent – as is sometimes suggested. But the one prepares the other. The labelling of others, the hatred that belittles or exalts others (always vertically), the hatred that no longer declares people as individuals, but only as a group, a collective, an identity (whatever that means) – hatred facilitates and promotes violence.

For those who are affected, it is initially a cognitive shock. It is confusing to be the object of hatred and resentment for no reason, for no reason, through no fault of your own. I can say this from my own experience as someone who experiences multiple forms of hatred or resentment on a daily basis, it is confusing. It takes away your social place. We are intersubjective, linguistic beings, we only understand ourselves in and through dialogue with others. And so it is not only the experience of love and recognition that shapes us, but also that of hatred and disregard.

The Bible knows about the dislocating effect of hatred, how hatred can get to you, take away your safe ground and make you think you are sinking into it.

Psalm 69 says:

Help me, O God,

for the waters

go up to my soul.

I am sunk in deep mud,

where there is no bottom;

I have fallen into the depths of the water,

and the flood swells over me.

I am weary with my cry,

My throat is parched.

My eyes are consumed with waiting for God.

Those who hate me without ceasing

are more than the hairs

on my head.

It’s a strange experience to be hated for something you’re not, for something you might be, but which doesn’t seem so meaningful to you, for your own body, your own gender, the colour of your skin, for the way you love or the way you believe, that would be something, the belief that I have chosen, it would be something that I choose, that I stand up for, for what I write, that would be something else that I also stand up for, the written word.

What would that mean if this hatred was always included in the price? If I were to expect hatred for my own affiliation, my own beliefs, for what I live or am, for a characteristic or a conviction that I share with others.

And so back to the lines of the cantata:

(3)

Certainly, the lines promise us consolation in the end. Bach promises us musical consolation. It is the promise that we are safe in faith, in the community of believers, who find themselves purified in the face of temptation.

Maybe that’s even true. Maybe it is true. Perhaps those of us

who feel challenged or antagonised, perhaps those who feel attacked and hurt, are uniting more closely. All those who are exposed to hatred as members of a religious, cultural or social community know that they belong more than ever.

But should that be right? Should that be necessary?

If one’s own identity is always linked to the injuries it experiences, what kind of identity is that?

The political theorist Wendy Brown speaks of a “wounded attachment”, an attachment to one’s own woundedness that imprisons members of disregarded communities, as it were. At some point, the pain, the trauma, the injury contributes more to one’s inner self-image than what else could: one’s own hopes, the experiences of deep happiness that faith or love or community could also create.

I would therefore like to warn against making hatred a natural, natural companion. Hatred is too deforming for that. It damages and destroys too much. Hatred and enmity should never be priced in, we should not think of them as normal. Our times sometimes sound as if the malicious, the shabby, the hostile behaviour is somehow more unquestionable than the kind, helpful, supportive behaviour.

If we want to confront hatred, then only by not subordinating

ourselves to it, by not normalising it, by not considering it to be obvious, but always and forever considering it to be irrelevant.

This requires the willingness to have experiences, to have other experiences, new and unexpected ones, it requires the willingness not to let old, earlier experiences overshadow everything, it requires the willingness to take time, to listen, to look, not just to take bits and pieces, not just scraps that only confirm what fear or pain dictate to us, it requires the willingness to be wrong, to allow ourselves to be hurt and to leave space, to leave possibilities for something,

that is better, fairer, more cheerful than the previous one.

That, by the way, is what faith promises us, that is what the cantata promises us, that is what we should embrace.

Thank you very much.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).