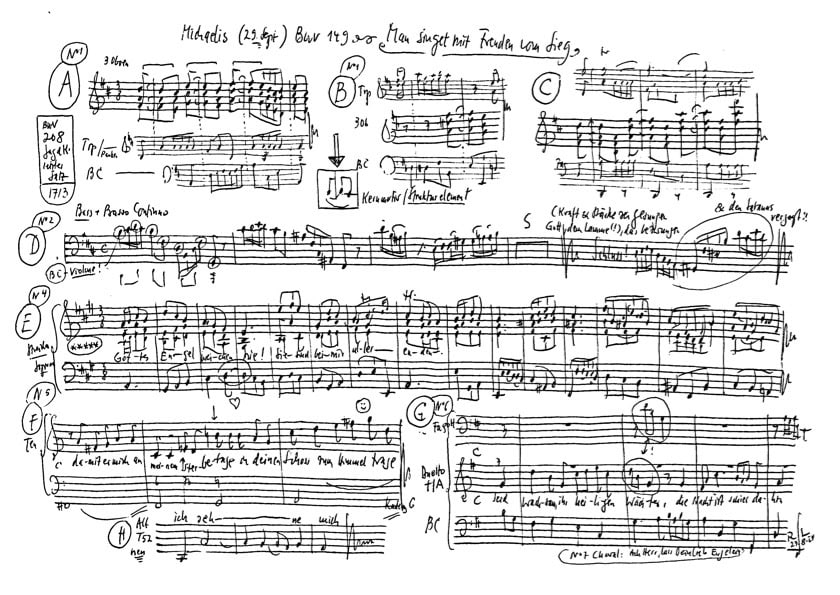

Man singet mit Freuden vom Sieg

BWV 149 // Feast of St Michael and All Angels

(They sing now of triumph with joy) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I-III, timpani, oboe I-III, bassoon, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Cornelia Fahrion, Gabriela Glaus, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Katharina Guglhör, Francisca Näf, Lea Scherer, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Joël Morand, Christian Rathgeber, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Israel Martins, Peter Strömberg

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Monika Baer, Elisabeth Kohler, Salome Zimmermann, Patricia Do, Aliza Vicente, Andrea Brunner

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Clara Espinosa Encinas, Laura Valentina Herzog

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer

Timpani/strong>

Martin Homann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Caspar Hirschi

Recording & editing

Recording date

13/09/2024

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

29 September 1728 or 1729, Leipzig

Text

Christian Friedrich Henrici 1725, movement 1: Psalm 118:15–16, movement 7: “”Herzlich lieb hab ich dich, o Herr”” (Matthias Schalling, written approx. 1569; first printed in 1571), verse 3

Libretto

1. Chor

«Man singet mit Freuden vom Sieg in den Hütten der

Gerechten:

Die Rechte des Herrn behält den Sieg, die Rechte des

Herrn ist erhöhet, die Rechte des Herrn behält den Sieg.»

2. Arie — Bass

Kraft und Stärke sei gesungen

Gott, dem Lamme, das bezwungen

und den Satanas verjagt,

der uns Tag und Nacht verklagt.

Ehr und Sieg ist auf die Frommen

durch des Lammes Blut gekommen.

3. Rezitativ — Alt

Ich fürchte mich

vor tausend Feinden nicht,

denn Gottes Engel lagern sich

um meine Seiten her;

wenn alles fällt, wenn alles bricht,

so bin ich doch in Ruhe.

Wie wär es möglich zu verzagen?

Gott schickt mir ferner Roß und Wagen

und ganze Herden Engel zu.

4. Arie — Sopran

Gottes Engel weichen nie,

sie sind bei mir allerenden.

Wenn ich schlafe, wachen sie,

wenn ich gehe,

wenn ich stehe,

tragen sie mich auf den Händen.

5. Rezitativ — Tenor

Ich danke dir,

mein lieber Gott, dafür;

dabei verleihe mir,

daß ich mein sündlich Tun bereue,

daß sich mein Engel drüber freue,

damit er mich an meinem Sterbetage

in deinen Schoß zum Himmel trage.

6. Arie — Alt und Tenor

Seid wachsam, ihr heiligen Wächter,

die Nacht ist schier dahin.

Ich sehne mich und ruhe nicht,

bis ich vor dem Angesicht

meines lieben Vaters bin.

7. Choral

Ach Herr, laß dein lieb Engelein

am letzten End die Seele mein

in Abrahams Schoß tragen,

den Leib in seim Schlafkämmerlein

gar sanft ohn einge Qual und Pein

ruhn bis am jüngsten Tage!

Alsdenn vom Tod erwecke mich,

daß meine Augen sehen dich

in aller Freud, o Gottes Sohn,

mein Heiland und Genadenthron!

Herr Jesu Christ, erhöre mich, erhöre mich,

ich will dich preisen ewiglich!

Caspar Hirschi

Ladies and gentlemen, allow me to start with a confession: When I hear Bach, my historian self immediately falls into a deep sleep. But the child in me is all the more awake. It gives me an experience of sound that seems to defy any rational analysis. With Bach’s music, I experience a rush of associations that stirs together sensory impressions from my childhood into a synaesthetic cocktail. This brings to bear a characteristic of music that no other art form possesses to the same extent. The first time you hear it is so strongly imprinted in your memory that it is recalled every time you hear it again. This is even more true if the music has already developed its sound in children’s ears.

I am probably one of the few people of my generation who first became acquainted with baroque music after the bedtime songs of my early years. The reason for this was my parents’ record collection. There was no television in our house, so we children learnt to play records before we could read. As soon as we were able to hold the discs by the side so as not to scratch them, we were allowed to take them out of the sleeve ourselves and put them on the player. I was particularly fond of the record sleeves that featured people in fascinatingly unusual costumes. As my parents knew nothing about hard rock and heavy metal, these were the baroque composers with their skirts, frills and wigs. Their historical portraits were arranged on the record sleeves to form a more or less artistic group portrait. The music was a potpourri of pieces by various Baroque greats. For me as a boy, this had the advantage that I quickly learnt to distinguish between a Vivaldi, a Telemann and a Purcell.

I also heard Johann Sebastian Bach for the first time on these discs. Even then, I perceived his music as a sound structure with its own intensity. The few pieces of his that were gathered together were very different from one another. There was a cantata, the text of which, significantly, I never memorised, and the “Badinerie” from the orchestral suites, the title of which I only remember because I was to play it myself on the flute more than ten years later.

What was decisive for my early childhood musical adventures, however, was that the record player in the parlour was next to a bookcase containing the thirteen volumes of “Grzimek’s Animal Life”. Every time the needle sank to the edge of the disc and the soft hissing sound started before the first notes, I picked up a volume by the Frankfurt zoologist from the shelf. As I couldn’t read yet, I immersed myself in the photographs and drawings of the animals, with bloody hunting and eating scenes particularly mesmerising. While the strings and winds of the baroque orchestras sounded from the loudspeakers, I suffered in the armchair with an oryx antelope that was being hunted to death by African wild dogs, or immersed myself in a series of underwater photos showing a blue shark eating a dolphin. Baroque music in general, and Bach in particular, was etched into my memory as the sound of the existential struggle for life and death.

This childhood imprint has stayed with me, even when I encountered Bach’s music in other contexts. No composer had such a strong influence on the holidays in my family as he did. Religion played a very minor role in my parents’ home. However, two holidays were celebrated with a sacred seriousness, as if rituals had their own power even when they were emptied of their religious content. My mother, a Zurich Zwinglian, acted as master of ceremonies. On Christmas Eve, she would decorate the tree alone while my father took us children on a tour of the cemetery to lay homemade wreaths of dried flowers on the graves of deceased friends and relatives. Before we left the house, we had to play Bach’s “Brandenburg Concertos” for my mum every time. I still don’t know why. However, it helped to make Christmas feel less like a celebration of birth for me and more like a celebration of survival and death.

Compared to Good Friday, however, Christmas was still a celebration of joy. In keeping with the reformed tradition, Good Friday was celebrated in strict silence. We weren’t allowed to go outside to play football, we had to be quiet in the house and we had fish with bones for dinner. The four of us children agreed that Good Friday was the worst day of the year. If we were in bed with a fever on that day, we considered it a stroke of luck. The situation only improved when my grandmother thought we were grown up enough to invite the whole family to the Good Friday concert of the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra. Not only did we get out of the house dressed all in black and were allowed to stretch our legs, but I was also able to let my imagination run wild while listening to the Mass in B minor or the “St Matthew Passion”. While the soloists and the Tonhalle choir sang about the last days of Christ’s life, the last minutes of the life of an animal immortalised in “Grzimek’s Animal Life” played out in my head.

In order to experience the intensity of my childhood listening experience, I had to consistently block out the meaning of the sung words in Bach’s music. I managed this brilliantly. Even in the “St Matthew Passion” sung in German, I hardly recognised any of the text. As a child, I was able to do with Bach’s libretti what I was no longer able to do so well as an adult, for example when the Swiss national anthem was played, much to my chagrin: to enhance the enjoyment of the music by ignoring the words. The sound of Bach’s music could come alive for me because I suppressed its original meaning.

When I bend over a text of Bach’s compositions for the first time with the cantata “Man singet mit Freuden vom Sieg”, I understand two things better at the same time: firstly, why this music has moved me so strongly from an early age, and secondly, why it was and still is useful for many listeners today to ignore the text in order to feel the music all the more strongly.

In my brief explanation, I will now have to wake the historian in me from a deep sleep. The ‘victory’ celebrated in Bach’s cantata is the famous fall from hell from the New Testament, when the archangel Michael and his heavenly hosts chase the apostate angel Satan and his devilish brood into the realm of darkness. The chorus and the aria in the initial triumphal song give an insight into how warlike Christian ideas of the events in heaven in the battle against evil could be until the dawn of the Enlightenment.

The recitative then introduces a new tone and a new voice into the cantata. The “I” speaking here is the Lutheran Christian struggling for his salvation, in the knowledge that no good deed or ecclesiastical mediation, but only divine grace, can free him from the clutches of the devil. This “I” already bears the first traits of the modern, self-centred individual who is in direct dialogue with God. It not only calls upon the heavenly army with “horse and chariot” to take away its fear of a thousand diabolical enemies, but – and this seems remarkable to me – it also appeals to its own personal angel to carry it into God’s bosom at the hour of death.

Despite this hint of modern individuality, the idea of a heavenly war against evil is probably just as foreign to most of us as the struggle for certainty of salvation of an early modern Protestant. It is difficult for us today to find a personal connection to this text. It is music that creates this connection by finding a timeless language for the deepest fears and hopes of the world of faith at that time, a language that still speaks to us. That is why we no longer need the words to let Bach’s music have an immediate effect on us, but thanks to these words we understand better why the effect is still so strong.

It now also seems to me that my childish reach for “Grzimek’s Animal Life” when listening to Bach’s music was instinctively appropriate. When the sounds from the record player mingled with the images of animals fighting for survival, as a young boy I experienced the existential intensity that Bach’s contemporaries must have similarly experienced when listening to his compositions with other images in their heads. I was thrown back onto the finiteness of my own life and the great mystery of death.

Thank you very much.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).