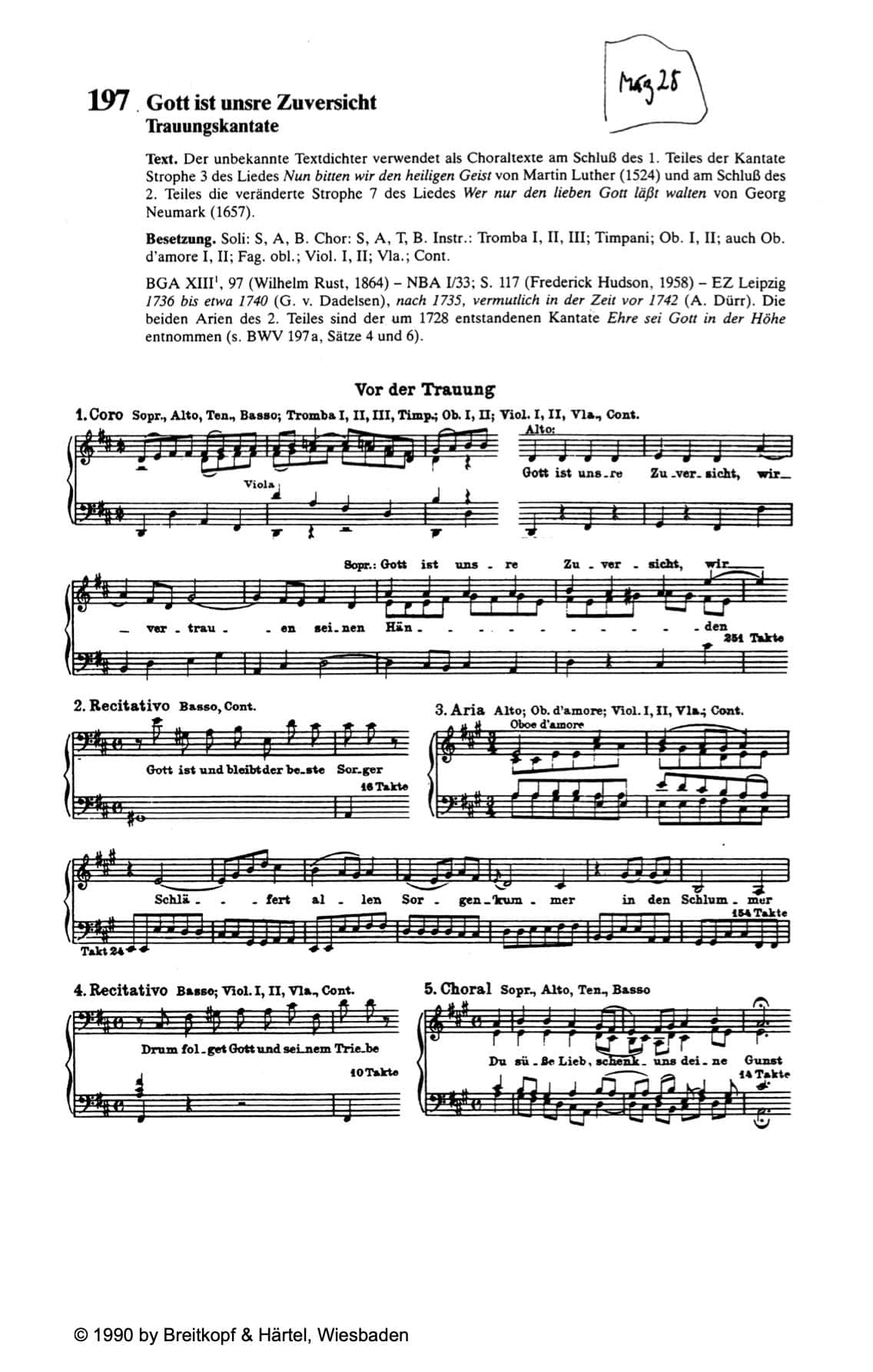

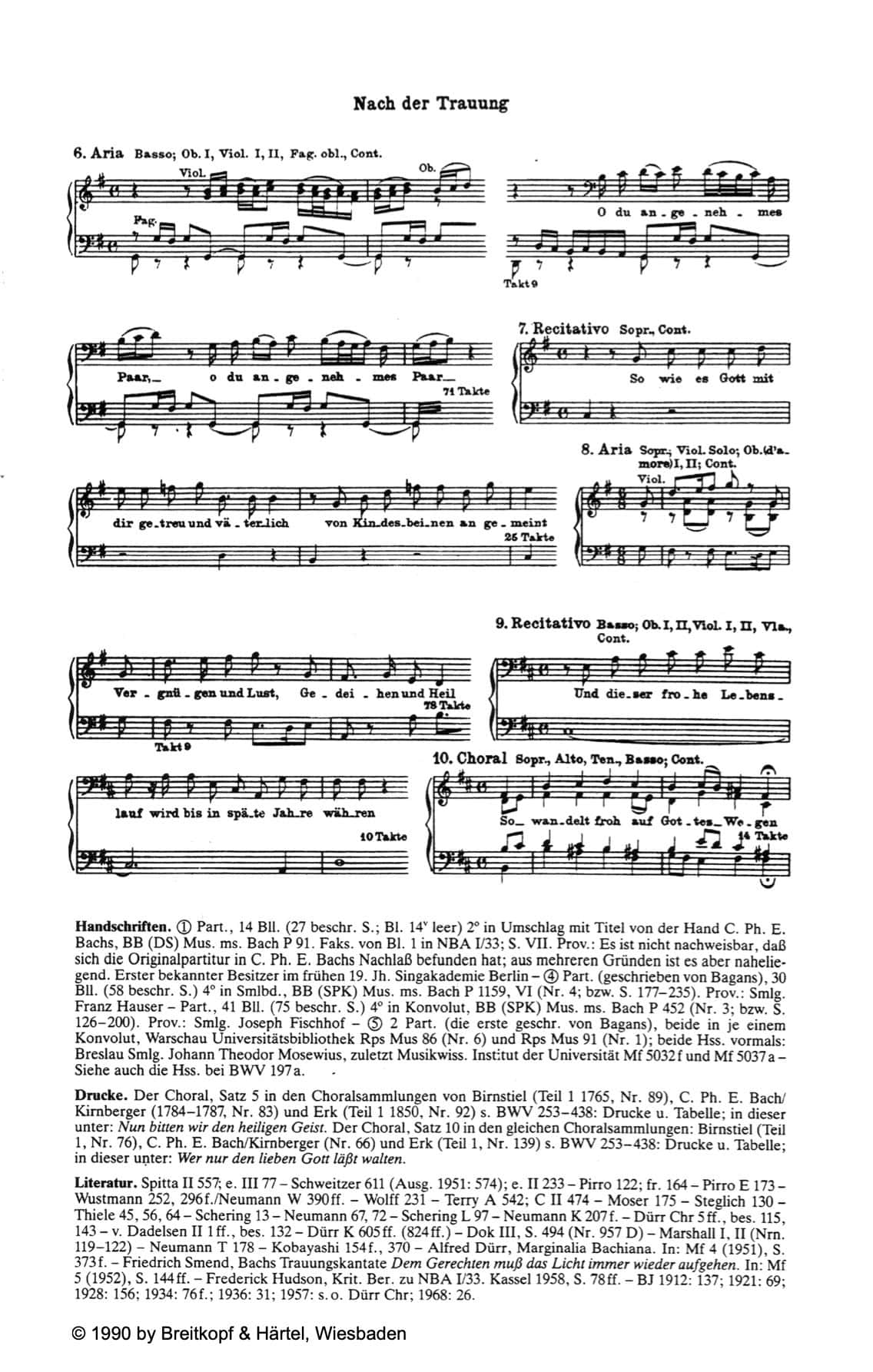

Gott ist unsre Zuversicht

BWV 197 // For a wedding

(God is our true confidence) for soprano, alto and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I-III, timpani, oboe I+II and oboe d’amore I+II, strings and basso continuo

Choir

Soprano

Alice Borciani, Katharina Held, Simone Schwark, Gunta Smirnova, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Baiba Urka

Alto

Nanora Büttiker, Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Alexandra Rawohl, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Klemens Mölkner, Joël Morand, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Christian Kotsis, Daniel Pérez

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Andrea Brunner, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler Gomes, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Jakob Valentin Herzog

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Josefa Winterfeld

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Jaroslav Rouček, Karel Mnuk, Pavel Janeček

Timpani

Georg Tausch

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Jonas Grethlein

Recording & editing

Recording date

21/03/2025

Recording location

Trogen (AR) // Evang. Kirche Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performanceFirst performance

Around 1736/1737, Leipzig or surrounding region

Text

Unknown poet

(Partly a parody of BWV 197a and BWV 249a)

Movement 5: “Nun bitten wir den Heiligen Geist”

(M. Luther, 1524), verse 3

Movement 10: (no text in surviving score):

“Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten”

(G. Neumark, 1641), probably verse 7

Libretto

1. Chor

Versus 1

Der Herr ist mein getreuer Hirt,

hält mich in seiner Hute,

darin mir gar nichts mangeln wird

irgend an einem Gute.

Er weidet mich ohn Unterlaß,

darauf wächst das wohlschmeckend Gras

seines heilsamen Wortes.

2. Rezitativ – Bass

Gott ist und bleibt der beste Sorger,

er hält am besten Haus.

Er führet unser Tun zuweilen wunderlich,

jedennoch fröhlich aus.

Wohin der Vorsatz nicht gedacht,

was die Vernunft unmöglich macht,

das füget sich.

Er hat das Glück der Kinder, die ihn lieben,

von Jugend an in seine Hand geschrieben.

3. Arie — Alt

Schläfert allen Sorgenkummer

in den Schlummer

kindlichen Vertrauens ein.

Gottes Augen, welche wachen,

und die unser Leitstern sein,

werden alles selber machen.

4. Rezitativ – Bass

Drum folget Gott und seinem Triebe.

Das ist die rechte Bahn.

Die führet durch Gefahr

auch endlich in das Kanaan,

und durch von ihm geprüfte Liebe,

auch an sein heiliges Altar,

und bindet Herz und Herz zusammen,

Herr! sei du selbst mit diesen Flammen!

5. Choral

Du süße Lieb, schenk uns deine Gunst,

laß uns empfinden der Liebe Brunst,

daß wir uns von Herzen einander lieben,

und in Fried auf einem Sinne bleiben.

Kyrie eleis!

Zweiter Teil

6. Arie – Bass

O du angenehmes Paar,

dir wird eitel Heil begegnen,

Gott wird dich aus Zion segnen

und dich leiten immerdar,

o du angenehmes Paar!

7. Rezitativ – Sopran

So wie es Gott mit dir

getreu und väterlich

von Kindesbeinen an gemeint,

so will er für und für

dein allerbester Freund

bis an das Ende bleiben.

Und also kannst du sicher gläuben,

er wird dir nie

bei deiner Hände Schweiß und Müh

kein Gutes lassen fehlen.

Wohl dir, dein Glück ist nicht zu zählen.

8. Arie – Sopran

Vergnügen und Lust,

Gedeihen und Heil

wird wachsen und stärken und laben.

Das Auge, die Brust

wird ewig sein Teil

an süßer Zufriedenheit haben.

9. Rezitativ – Bass

Und dieser frohe Lebenslauf

wird bis in späte Jahre währen.

Denn Gottes Güte hat kein Ziel,

die schenkt dir viel,

ja mehr, als selbst das Herze kann begehren.

Verlasse dich gewiß darauf.

10. Choral

So wandelt froh auf Gottes Wegen,

und was ihr tut, das tut getreu!

Verdienet eures Gottes Segen,

denn der ist alle Morgen neu:

denn welcher seine Zuversicht

auf Gott setzt, den verläßt er nicht.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Jonas Grethlein

‘God is our confidence, we trust in his hands.’ This is how the cantata begins, the first part of which we have just heard. It was composed by Bach for a church wedding. We are also in a church today, but not at a wedding, but at a secular concert. The text of the cantata also seems far removed from our world: trust in God is at its centre, not only introducing the cantata but also bringing it to a close: ‘For whoever puts their trust in God will not be abandoned by him,’ it says at the end. Secularisation has not completely banished God from modern society, but it has made him one ideological option among many: Some believe in God, others don’t, and still others don’t want to commit to whether or not there is a God.

There also seems to be no room for confidence in our time. The urgency with which politicians and psychologists appeal to us to look to the future with confidence testifies to how difficult it is for us to be confident. The conflict in the Middle East has escalated, the war in Ukraine continues, the economy is not picking up, many observe a polarisation of society and are concerned about the success of populist politicians. Above all this lies a dark cloud of climate change. We look to the future with confidence – but how can we do so when that future seems threatened, when we don’t know what state we are leaving the Earth in for our children and grandchildren?

Should we then concentrate entirely on the music, the instruments and the sound of the voices, ignoring what they are singing? Does the cantata move us only aesthetically, without saying anything to us? I must object to that ex officio – after all, it is my job to give you a few thoughts before the second part of the cantata. But I also want to object to that, because even though the cantata seems foreign to us in its world view and mood, it offers images and concepts that can inspire us to reflect, even and perhaps especially today.

Let us begin with what is opposed to confidence and is directly accessible to us in the present-day polycrisis. In the first aria, the alto, today the countertenor Alex Potter, sings about God: ‘Put to sleep all sorrows / in the slumber / of childlike trust’. A beautiful image: a child falls asleep, his breathing slows and becomes regular; his eyelids flutter a few more times before they finally lower; trusting his parents, the child feels safe and lets himself fall asleep. His worries and concerns also fall asleep with him.

If we are troubled by something that went badly in the past, then like confidence, worries are directed towards the future. The place of worry in our lives is explained by an ancient legend found in a collection of fables from the imperial era: ‘Once upon a time, worry was crossing a river, we read there, when she saw clayey soil. She took a piece of it and began to shape it. While she was contemplating what she had created, Jupiter, the father of the gods, approached her. Worry asked him to give her clay figure a mind. Jupiter granted her wish. But when Worry wanted to give the figure her name, Jupiter refused her this wish – the being should bear his name. While Worry and Jupiter were arguing over the name, the Earth also rose up and demanded that the figure should be named after her. After all, clay comes from her.

Unable to agree, the disputants took Saturn as their judge. He pronounced the following verdict: ‘You, Jupiter, because you provided the spirit, shall receive the spirit at its death; you, Earth, because you provided the body, shall receive the body. However, since Worry was the first to form this being, Worry may possess it as long as it lives. As for the name, the being shall be called ‘homo’, human, because it is made of earth, ‘humus’.’

You don’t have to be a classical philologist to come across this story. It can also be found in Martin Heidegger. In Being and Time, he presents the fable as an early, poetic reflection on care as the temporal basic structure of existence. Heidegger recognises the importance of the future for human existence: unlike animals, humans are open to the future; they are not determined by instinct, but can and must project themselves into the future. But Heidegger defines this openness one-sidedly as care. However, alongside the anxious view of what is to come, there is also hope, which expects something good from the future. When hope intensifies into certainty, it becomes confidence.

Our cantata takes this temporal openness of the human being as its starting point and names both sides. But in trusting in God, Bach puts confidence in the foreground and lets it calm worry, even put it to sleep. Concern is transferred to God as a form of care. Thus the bass, today Dominik Wörner, proclaims at the beginning of his first recitative: ‘God is and remains the best provider, / he keeps the best house.’ Another meaningful image: the world as God’s house, God’s care for man as housekeeping.

In Greek, housekeeping is called oikonomia, in Latin oeconomia. Our word ‘economy’ is derived from the ancient term, but the two are not synonymous. In addition to the economic dimension, oeconomia also encompasses the religious, social and legal aspects of household management. Along with material provision, it encompasses the ritual worship of the gods, the relationship of the paterfamilias to his wife and children, and the treatment of slaves and employees.

Oeconomia is a very broad concept. Ancient literary critics used it to refer to the arrangement of events in a narrative, or the plot. In turn, early Christian authors spoke of God’s plan of salvation as an economy. The history of the world is a household that God administers in the best possible way. Just as a landowner takes care of everything, his fields and animals as well as his family and workers, God has also set up his creation so that all living things have their place. Therefore, people can look to the future with confidence, not only to their further life in this world, but also to the hereafter, where resurrection awaits them. When Bach writes ‘God is and remains the best provider, / he keeps the best house’, he means this Christian economy of salvation.

Economics is also important in our world, but without the dimension of the hereafter. On the one hand, the ups and downs of the economy dominate our headlines. ‘It’s the economy, stupid,’ said Bill Clinton in 1992, winning the US presidential election with this slogan. Only rarely do presidents and parties in Western democracies manage to stay in power when the economy is not doing well. The cultural sector also suffers from a sluggish economy – concerts and theatre performances, exhibitions and readings have to be financed somehow.

But the economy is also a cause for concern in another way. Climate change is essentially the product of the pursuit of growth, which is deeply embedded in our economy. This dynamic is vividly illustrated by the stock market. The curve of the DAX may slump briefly, as it did during the coronavirus pandemic, but it is inexorably rising from the bottom left to the top right. But not only production and gross domestic product are increasing, so is the emission of pollutants. As early as 1972, the Club of Rome warned of the limits to growth and concluded that a continuation of our economic activities would lead the planet into the abyss. Politicians with an affinity for technology rely on new technologies that are supposed to reduce the economy’s consumption of resources without slowing down its growth. Activists are sceptical – they believe that only an end to economic growth can save the balance on Earth.

Our cantata also speaks of growth. The soprano Miriam Feuersinger begins her aria with the promise: ‘Pleasure and delight, / prosperity and salvation / will grow and strengthen and refresh.’ Before that, she stated in the recitative: ‘Your happiness cannot be counted,’ and in the concluding recitative, the bass promises: ‘For God’s goodness has no end, / it gives you much, / yes, more than even the heart can desire. / You can be sure of that.’ In Bach’s economy of salvation, limitless growth is the promise of God’s grace; in modern economics, it has become a threat to humanity and the Earth.

In the cantata, God appears not only as a sustainable economist, but also as a father, and humanity as his children. Their trust in him is childlike, as we have already heard. In the soprano recitative, it also says: ‘Just as God has treated you / faithfully and fatherly / from childhood, / so he will remain / your very best friend / for ever.’ In the next sentence, the soprano promises humans good ‘through the sweat of your brow and your toil’.

With Hannah Arendt, we can translate this image of God’s hardworking children into secular language. Whereas Heidegger defines existence through being towards death, Arendt focuses on birth. We humans, according to her thesis, are fundamentally characterised by our ‘birth’. The possibility of a new beginning is grounded in being born. Just as a child enters into life, we can always make a fresh start.

Human activity is also emphasised in the concluding chorale of our cantata: ‘So walk gladly in God’s ways, / and what you do, do faithfully! / Earn your God’s blessing, / for it is new every morning; / for whoever puts their trust / in God, he will not abandon them.’ Just how much Bach emphasises human endeavour here is shown by a comparison with the model on which he liberally draws, the hymn ‘Wer nur den lieben Gott läßt walten’ (Let God Rule). The original has ‘And trust in heaven’s abundant blessings / They will be renewed with you’, whereas in our cantata it is ‘Earn your God’s blessing, / For it is new every morning’. Here, Bach is on a collision course with the Protestant doctrine of justification, according to which a person can only become righteous through God’s grace, not through their own actions.

But let’s leave theology aside. Confidence, that is one message of our cantata, is not a passive attitude. Even when it is directed towards God, it is closely linked to human activity. Optimism gives us the strength to start anew every morning. At the same time, optimism is strengthened by being active. Those who experience their own actions as effective develop trust. Our cantata highlights the limits of human beings – whether their works bear fruit is not in their hands – but it emphasises the industriousness of their actions.

However different the context of the original performance and however remote Bach’s world of thought may seem to us, we cannot ignore the text when we hear the music. However we follow the performance, whether as Christians or Jews, as Muslims or Buddhists, as atheists or agnostics, it leads us with confidence and concern into a fundamental area of tension in our lives. Above all, however, this meditation finds expression in the sound of the instruments and the voices of the singers. Bach not only allows us to reflect on hope – in the second part, which we will now hear, he also allows us to feel it with his music, especially in a time of crisis.