Amore traditore

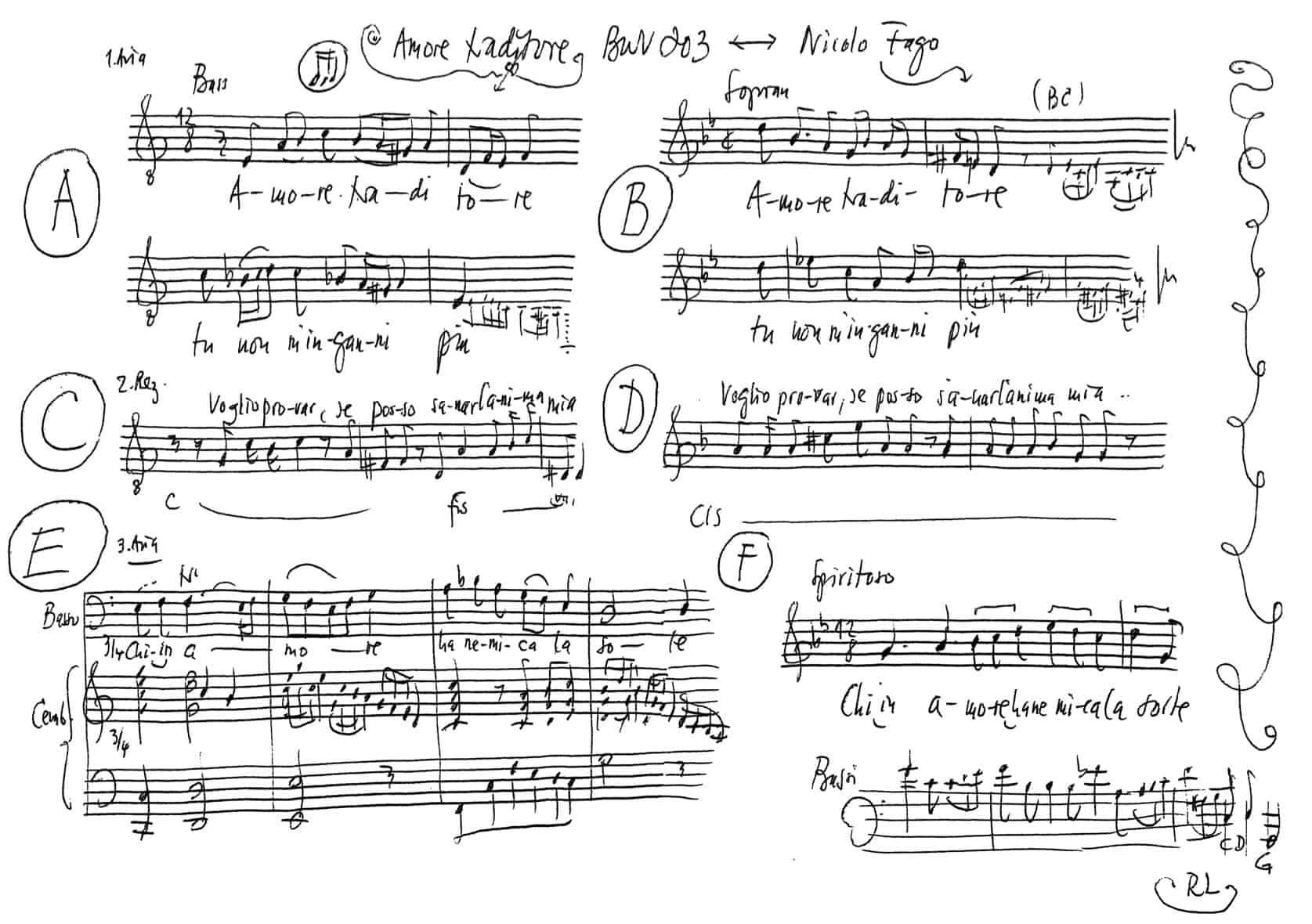

BWV 203 // saecular cantata

For bass and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Bass

Dominik Wörner

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Alice Borciani, Maya Amrein, Johannes Lang, Dominik Wörner

Reflective lecture

Speakers

Johannes Lang

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/06/2022

Recording location

Rorschach SG (Schweiz) // Würth-Haus

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

“First performance

Unknown (Köthen in 1719?)

Text

Source unknown”

Libretto

1. Arie — Bass

Amore traditore,

tu non m’inganni più.

Non voglio più catene,

non voglio affanni, pene,

cordoglio e servitù.

1. Arie — Bass

O Liebe, du Verräterin,

von dir sag ich mich frei.

So werf ich ab die Ketten,

mich aus der Qual zu retten,

aus Kummer und Sklaverei.

2. Rezitativ — Bass

Voglio provar,

se posso sanar

l’anima mia dalla piaga fatale,

e viver si può senza il tuo strale;

non sia più la speranza

lusinga del dolore,

e la gioja nel mio core,

più tuo scherzo sara nella mia costanza.

2. Rezitativ — Bass

Nun will ich seh’n,

ob’s möglich, mein Herz

wieder zu heilen von dem tödlichen Schlage.

Dein Pfeil soll nimmermehr mein Herz verwunden,

nicht sei die Hoffnung länger

mein Trost in bittern Schmerzen,

und nicht bringt dein zärtlich Kosen,

dein bezaubernder Reiz den Entschluss zum Wanken.

3. Arie — Bass

Chi in amore ha nemica la sorte,

è follia, se non lascia d’amar,

sprezzi l’alma le crude ritorte,

se non trova mercede al penar.

3. Arie — Bass

Lass dich nimmer von der Liebe berücken,

wenn das Glück dir Gewährung nicht gibt.

Brich die Fesseln, die eng dich umstricken,

wirst nicht endlich du wiedergeliebt.

Johannes Lang

Reflection on the “Italian Bach

Held on the occasion of the concert of the J. S. Bach Foundation in the Würth House, Rorschach, on 24 June 2022

Bach’s musical development is intensively linked to Weimar. When Bach came to Weimar in July 1708, he found a musical life at court that brought entirely new influences. In order to trace the development, it is worthwhile to first look at Bach’s cantata style “before” Weimar.

- Pure choral texts or pure biblical text (Lutheran Orthodoxy)

- Frequent instrumentation with two tenor voices/violas

- No recitatives (avoidance of an operatic style)

- Examples are BWV 4, 131 and 106

Music example:

BWV 4, Sinfonia- Beginning (Listen here for the affect in which the chorale quotation is incorporated).

In Weimar, Bach found a “court of the world”, supplied with the best music from Europe, especially from Italy. What was the fascination?

Listen to the following music examples:

BWV 593, 2nd movement

https://youtu.be/Z-xvW920gqk?t=249

Transcribed for organ by Bach in Weimar, this Concerto is full of expansiveness and poetry in the second movement, the kind that almost only Vivaldi can conjure up.

BWV 593, 3rd movement

The last movement is bursting with virtuosity and fire. The “concertante principle” with alternating solo and tutti parts can also be heard well. Here, too, there are passages full of breadth and very slow harmonic tempi.

This music must have been played up and down the court and was so popular that it did not stop at the church doors: Bach certainly not only transcribed these Vivaldi concertos for the organ, he certainly played them. In addition, there are fugues based on themes by Italian composers such as Legrenzi and Corelli, as well as almost innumerable transcriptions for harpsichord of Vivaldi concertos.

In addition, there was a highly talented young prince in Weimar who composed himself and whose concertos Bach transcribed for the organ.

Music example:

BWV 595

How did this influence Bach’s own style?

First, the question of why Bach did not compose instrumental concertos based on the Italian model in Weimar, but only in Köthen. This was certainly due to the fact that his rank was lower than that of Kapellmeister. Bach was only promoted to the third position after he was given the additional position of concert master at the end of 1713 and then at the beginning of 1714, following a successful application to Halle. From then on, Bach had to compose cantatas every month. The Italian influence is already clearly audible in the first cantata for Palmarum 1714.

Music examples:

BWV 182, Sinfonia (Listen to the Italian affect of expansiveness and poetry)

https://youtu.be/dc8nT_dHCjk?t=40

The instrumentation is nevertheless still very similar to the early works before Weimar (two violas, etc.) and the style of the opening chorus is in the form of the permutation fugue, as can also be found in the pre-Weimar period.

BWV 182, Recitativo

https://youtu.be/dc8nT_dHCjk?t=366

This is a very early example of a recitative which, except for the beginning, is more of an arioso.

BWV 182, final movement

https://youtu.be/dc8nT_dHCjk?t=1444

Form of a virtuoso concerto fugue.

How did Bach’s style develop further in Weimar? At the end of his time in Weimar, he composed BWV 70, a work which unfortunately has not been preserved in the original Weimar version.

Music example:

BWV 70, Entrance Chorus

https://youtu.be/PXaeE0J4pxg?t=30

Here Bach already seems to have arrived completely in his personal style with internalised Italian influences:

- concertante principle (choir comes only after prelude)

- flat passage in the prelude with slow harmonic progression

- Unison conclusion at the end of the prelude builds a bridge to BWV 593

Conclusion:

The Italian style had a decisive influence on Bach. This resulted in a synthesis that Bach himself obviously liked so much that he had the Weimar cantatas performed again in Leipzig in an edited form.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).