Sie werden aus Saba alle kommen

BWV 065 // Epiphany

(They shall from Sheba all be coming) for the Feast of Epiphany, for tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn I+II, recorder I+II, oboe da caccia I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger Alexa Vogel, Anna Walker, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Dina König, Francisca Näf, Simon Savoy

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Achim Glatz, Tobias Mäthger, Joël Morand

Bass

Serafin Heusser, Simón Millán, Daniel Pérez, Retus Pfister, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Ildiko Sajgo, Cecilie Valter, Aliza Vicente Aranda

Viola

Peter Barczi, Sarah Mühlethaler, Rafael Roth

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Guisella Massa

Corni da caccia

Stephan Katte, Olivier Picon

Recorder

Annina Stahlberger, Teresa Hackel

Oboe da caccia

Andreas Helm, Thomas Meraner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Arend Hoyer

Recording & editing

Recording date

15/01/2021

Recording location

St.Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

6 January 1724, Leipzig

Text

Isaiah 60:6 (movement 1); Johann Spangenberg (movement 2); anonymous (movements 3–6); Sebastian Franck (movement 7)

In-depth analysis

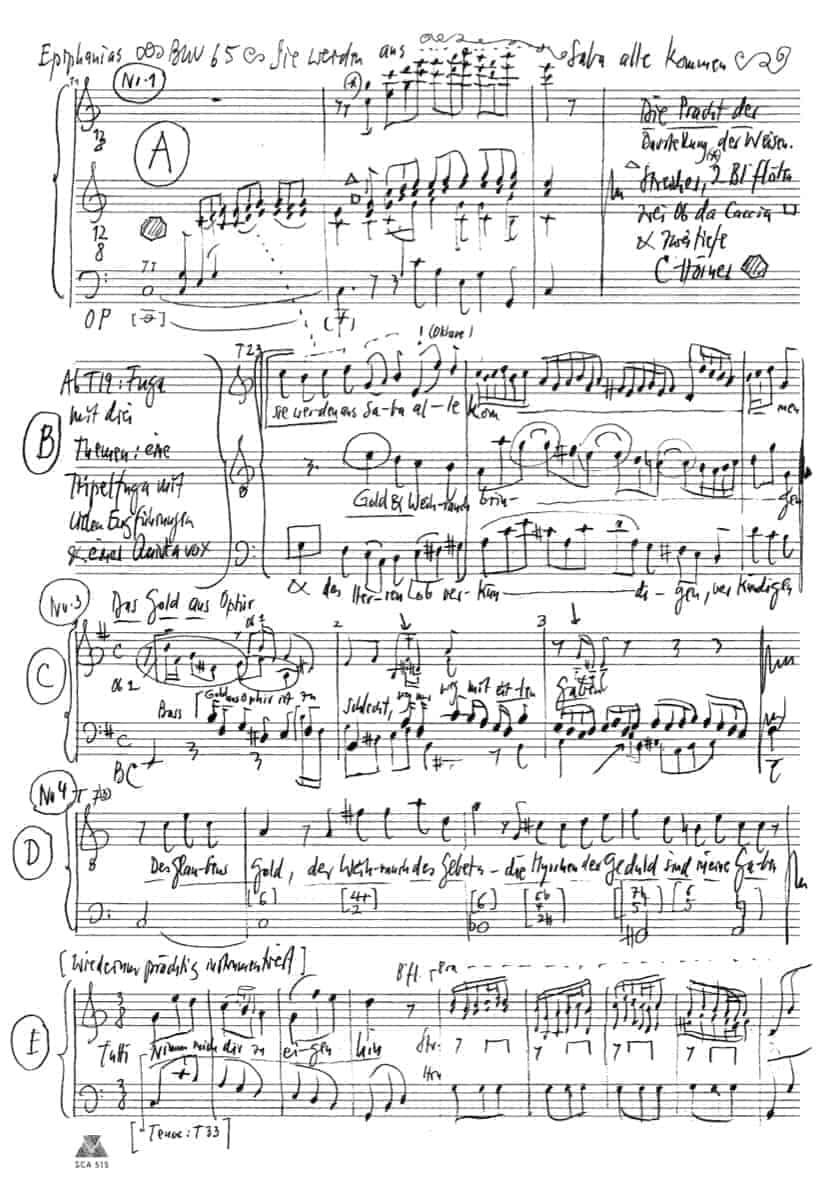

Cantata BWV 65 was first performed on 6 January 1724. As befits the Feast of Epiphany, its introductory chorus is characterised by festive tones and a buoyant, ceremonial style. Commencing with splendid horns paired with pastoral recorders and oboes da caccia, the opening section portrays the kings and shepherds congregating at the manger in a scene seemingly bathed in the light of the morning star. The series of instrumental passages then give way to a choral section of imitative lines and syllabic phrases from which an expansive fugue almost imperceptibly emerges. A complex structure with regular countersubjects ensues, ere Bach reintroduces the festive horn figures and unison passages of the opening section to round off the movement. The fact that he later reused the majestic, flowing introductory theme in his Organ Prelude in C Major BWV 547/1 proves the value he placed on this catchy Inventio.

Surprisingly, this introduction is followed by a further tutti movement, a chorale setting of “Die Kön‘ge aus Saba kamen dar” (The kings from out Sheba came then forth), a verse from the medieval hymn “Ein Kind geborn zu Bethlehem” (A child is born in Bethlehem). While the archaic melody served to bring the congregation of 1724 closer to the Feast Day events lauded in the previous concertante setting, copies from the chorale-obsessed 19th century indicate that this movement was then mistaken for the actual beginning of the cantata.

In a style typical of the baroque, the following bass recitative alludes to and combines different narratives from both the Old and New Testaments. As prophesised by Isaiah, the seed of Jesse’s tree has bloomed in Bethlehem, and the Magi with their gifts represent a summons to go to the manger and, like blessed Simeon, recognise baby Jesus as the “Licht der Heiden” (light of the nations). The bass aria, featuring a warm and deep oboe da caccia melody over a laconic continuo accompaniment, then reinforces the notion that the most noble gift humankind can offer is a faithful heart. Accordingly, even gold from the land of Ophir, the ancient African Eldorado, pales in comparison: at the manger, all idle treasures of the world are inadequate. That this criticism of excavating Mammon and mining earth’s treasures laid an axe to the root of Sachsen prosperity – and was belied by Bach’s own shareholdings in later years – renders this moral position somewhat akin to an over-zealous New Year’s resolution.

The tenor recitative restates this imploring plea to not disdain the humbly offered heart – a heart that as a creation of God carries within it “des Glaubens Gold” (the gold of faith), “Weihrauch des Gebets” (frankincense of prayer) and “Myrrhen der Geduld” (myrrh of patience). The human, transformed by God through faith, becomes earth’s greatest treasure, which bears the promise of a reunion with the Saviour in heaven.

Thus reconciled with God, the tenor embarks on an aria, a minuet in sacred style that in its mixture of magnificence and playfulness harks back to the introductory chorus. In this elegant, mellifluous setting, the noble heart is portrayed as a precious gift that enables the faithful to approach the Highest with both confidence and humility – an ideal combination that proved perpetually elusive to Bach in his dealings with his own superiors.

Following this concertante, suite-like setting, listeners might fairly expect to hear a summary of the cantata’s message in the closing chorale. Bach, however, left no indication of his selected text in the score, making the choice of chorale verse a matter of interpretation. Whereas the New Bach Edition uses a verse from Paul Gerhardt’s hymn “Ich hab in Gottes Herz und Sinn” (I have to God’s own heart and mind), this recording employs a text from the Coburg song book of 1645, a suggestion put forth by Martin Petzold.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Sie werden aus Saba alle kommen, Gold und Weihrauch bringen und des Herren Lob verkündigen.»

2. Choral

Die Kön’ge aus Saba kamen dar,

Gold, Weihrauch, Myrrhen brachten sie dar,

alleluja, alleluja!

3. Rezitativ — Bass

Was dort Jesaias vorhergesehn,

das ist zu Bethlehem geschehn.

Hier stellen sich die Weisen

bei Jesu Krippen ein

und wollen ihn als ihren König preisen.

Gold, Weihrauch, Myrrhen sind

die köstlichen Geschenke,

womit sie dieses Jesuskind

zu Bethlehem im Stall beehren.

Mein Jesu, wenn ich itzt an meine Pflicht gedenke,

muß ich mich auch zu deiner Krippen kehren

und gleichfalls dankbar sein:

Denn dieser Tag ist mir ein Tag der Freuden,

da du, o Lebensfürst,

das Licht der Heiden

und ihr Erlöser wirst.

Was aber bring ich wohl, du Himmelskönig?

Ist dir mein Herze nicht zuwenig,

so nimm es gnädig an,

weil ich nichts Edlers bringen kann.

4. Arie — Bass

Gold aus Ophir ist zu schlecht,

weg, nur weg mit eitlen Gaben,

die ihr aus der Erden brecht!

Jesus will das Herze haben.

Schenke dies, o Christenschar,

Jesu zu dem neuen Jahr!

5. Rezitativ — Tenor

Verschmähe nicht,

du, meiner Seelen Licht,

mein Herz, das ich in Demut zu dir bringe.

Es schließt ja solche Dinge

in sich zugleich mit ein,

die deines Geistes Früchte sein.

Des Glaubens Gold, der Weihrauch des Gebets,

die Myrrhen der Geduld sind meine Gaben,

die sollst du, Jesu, für und für

zum Eigentum und zum Geschenke haben.

Gib aber dich auch selber mir,

so machst du mich zum Reichsten auf der Erden;

denn, hab ich dich, so muß

des größten Reichtums Überfluß

mir dermaleinst im Himmel werden.

6. Arie — Tenor

Nimm mich dir zu eigen hin,

nimm mein Herze zum Geschenke.

Alles, alles, was ich bin,

was ich rede, tu und denke,

soll, mein Heiland, nur allein

dir zum Dienst gewidmet sein.

7. Choral

Hier ist mein Herz, Herr, nimm es hin,

Dir hab ich es ergeben.

Welt immer fort aus meinem Sinn

Mit deinem bösen Leben:

Dein Tun und Tand hat nicht Bestand,

Das bin ich worden innen.

Drum schwingt aus dir sich mit Begier

Mein freier Geist von hinnen.

Arend Hoyer

Bach and the emergency chaplain

The more I engage with Bach’s music, the more I become aware that it transports me to another world every time. It is not the 300-year-old sounds that do this, or the flowery lyricism of the cantatas – at some point you get used to them and they become present to you. No, the demand that this music, this poetry clothed in sound, makes on me confronts me with an understanding of the world for which my mind was not made. What is brought to me is experience compressed into word and sound, is science clothed in the garb of poetry and music.

At this point, it is important to become aware of the enormous cultural upheaval that just barely spared Leipzig during Bach’s lifetime, or whose harbingers are only just reaching the city and just barely touching Bach’s music without influencing it more deeply. Leipzig, which is actually a cosmopolitan trade fair city, is still only on the threshold of the Enlightenment with its cult and music – I understand this to mean the younger, hard Enlightenment, as clearly represented by an Immanuel Kant a few decades after Bach; the form of enlightenment that no longer seeks to mediate between the book of nature and the book of revelation, but instead places the individual entirely on his or her own understanding and no doubt still accepts nature, but no book, no tradition – and even less tolerates a story in the canon of discourses guiding knowledge, such as that of the wise men from the Orient. What we have since become accustomed to is knowledge without heritage, without collected, mediated knowledge, without Greek or Latin.

But this is precisely the basis of the culture within which Bach writes his music: Greek and Roman, Near Eastern antiquity, books without end – not to mention the Book of Books – names, references, a compilation of doctrinal formations and individual doctrines, a layering of experiences, contexts and narratives; a world that somehow and mysteriously holds together, a unity of theology, philosophy, geometry, natural history, mathematics, astronomy, rhetoric: Science as art and art as science, all this regionally different and denominationally competing, but ultimately coherent, forming a mystical unity, bringing this world and the other world into conversation. Art liquefies the knowledge that has been collected and compressed over the centuries: Through measure, number, and weight, all phenomena can be accessed and actualized: Christian revelation with the cultural treasures of pagan antiquity, preaching with Greek and Roman rhetoric, opera with Jesus, worship with everyday life. Old and new complement each other, insight and devotion, pleasure and seriousness, humour and truth, order and freedom, pomp and simplicity, poverty and excess: all together without distinction, the one merging into the other, nature and spirit, knowledge and faith, body and soul, thinking and feeling, the individual and the whole, contradiction and wisdom, I, you and we, above and below, what is currently fashionable with the tried and tested. This is Bach’s science – where there is the All-One to see, hear, feel and understand and all questions are answered if you navigate within the systems just long enough.

And we today stand in a completely different place and have become completely blind to the All-One. The wise men from the Orient, mutated into kings, are orientalizing romance and nothing more. A fragrance from the Arabian Nights with its precious woods, spices, incense, a caravan led over dunes by moonlight and comet light with its camel drivers, musicians beating muffled drums and playing nasally shawms. Quite appropriately, we cannot help but smile at the staging of the royal procession in the first two movements of this cantata and dismiss as sentimental the attempt at actualization in the arias and recitatives that follow.

Indeed: sentimentality and kitsch have no place in my work as a chaplain, especially as an emergency chaplain. Here a logic has come to its end: A small business was painstakingly created and brought to flower. Now, however, a police officer sits at the breakfast table, which is only half cleared, the five-month pregnant wife with an immigrant background speaks little and only broken English, the district doctor examines the body of the forty-year-old who died of a heart attack this morning.

This is our world, facts that our life stories will come up against at some point, sooner or later. No escape, no “sweet consolation,” as in the sermons of a Salomon Deyling, who worked in Leipzig at the same time as Bach. No being lifted up into a greater whole, no confession except to oneself and to one’s own achievement. Important, very important, of course, the relatives and the circle of friends. But even there the helpless answer to all questions remains the same. At some point someone pronounces it: “Life goes on.” That’s as far as our horizon goes.

And I, as a pastor, in the midst of it, quietly encourage to find a language again for what we have experienced and thus prevent post-traumatic disorders.

Far closer to us than the Kings of Sheba and the grateful heart of the Bach Cantata is the story of the failure of one Torquato Tasso, as described by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his eponymous artist drama. Tasso lives as an artist at an Italian court and, according to Goethe, fails because of unrequited love, misunderstood art and the lack of freedom that comes with his status. Shortly before the curtain falls, Goethe has him speak before Antonio, his personal enemy and nonetheless companion in adversity:

Broken is the wheel, and it cracks

The ship on all sides. Bursting tears

The floor’s coming up under my feet!

I’ll take you in hand and foot!

So at last the skipper still clings

Stuck to the rock he was supposed to fail.

This image of the sailor who holds on to the same rock on which his ship was wrecked accompanies me as a pastor and in general as a theologian and observer of my time and my own life.

It is a counter-intuitive and at the same time inescapably logical train of thought: to what else

should one cling but to the rock on which his ship wrecked? So we are guided and steered by facts far more than by thoughts and fail, one sooner, the other later on some rock, that of our own health, that of an economic crisis, a crisis of faith, orientation or relationships, clinging on, looking for answers and of course finding none – except: “Life goes on. ”

A corps à corps with a life that gets in the way like Tasso’s rock, which appears at a time when one’s logic has come to an end. To the question “What now? ” we get the only answer: keep going! The body of the man, who of course did not want to go to the doctor the night before, still lies intubated on the floor. The child they share is growing in the wife’s womb. Is this not a mocking symbol of the inescapable “life goes on”?

Back to Bach: the

sailor with his broken rudder naturally also has a place with him – in the ideal-typical I, in the spiritual – as well as secular – stories and dialogues told in the cantatas, passions and oratorios. But theologically and philosophically speaking, the ground beneath one’s feet doesn’t just break at the end of the drama, but at its beginning. Bach’s I’s have long been aware of their abysses, struggle through the tangle of life, gasp for breath, accuse themselves and are carried along by poetry and music, which together re-stage figures from the Bible, but also a Hercules at the crossroads, astrologers and kings, in order to better accompany this errant I on its process of reconciliation with its own existence. In my eyes, Bach’s music is the knowledge of past millennia that is made available in each case, which, through harmonies, rhythms and echoes of further melodies and texts that are sometimes surprising even to our ears, opens up to the dispatcher as well as to the mind, and helps both to detach themselves from the rock of their own life’s tragedy and, accompanied and encouraged, to venture out onto the open water again.

In the course of my pastoral work I stand, sit and wander through the family home of the deceased, sometimes talking to the mother, sometimes to the father, sometimes to the neighbour. For a time I sit with the young widow in the attic. Relatives come to see her and leave. And I sit upright like a Mesopotamian sculpture from the Louvre, not taking up much space, hands clasped together, but sharing in what is happening and speaking when the silence becomes oppressive. This I see as my task for the moment, looking at the woman with benevolence as a mostly silent witness to a truth that must still remain barred to the woman, to those present, and to myself by the massive rock on whose hard flank her husband and her own life failed this morning. Perhaps those present read in my attitude and in my features the message, “Life goes on.” But perhaps they can also read from this scene the solidarity of those who have failed, and from the affection of a stranger, but friendly and almost familiar person, they can draw courage again to find a new language for the future life enriched with new knowledge and new experiences.

Bach and his science remain foreign to me. Nevertheless, this helps me not to lose my footing in a time exposed to the roughness of facts and to regard myself as an often silent witness of a life that has always meant well with us – and means well with us now.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).