Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern

BWV 001 // For the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary

(How beauteous beams the morning star) for soprano, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, corno I+II, oboe da caccia I+II, strings and continuo

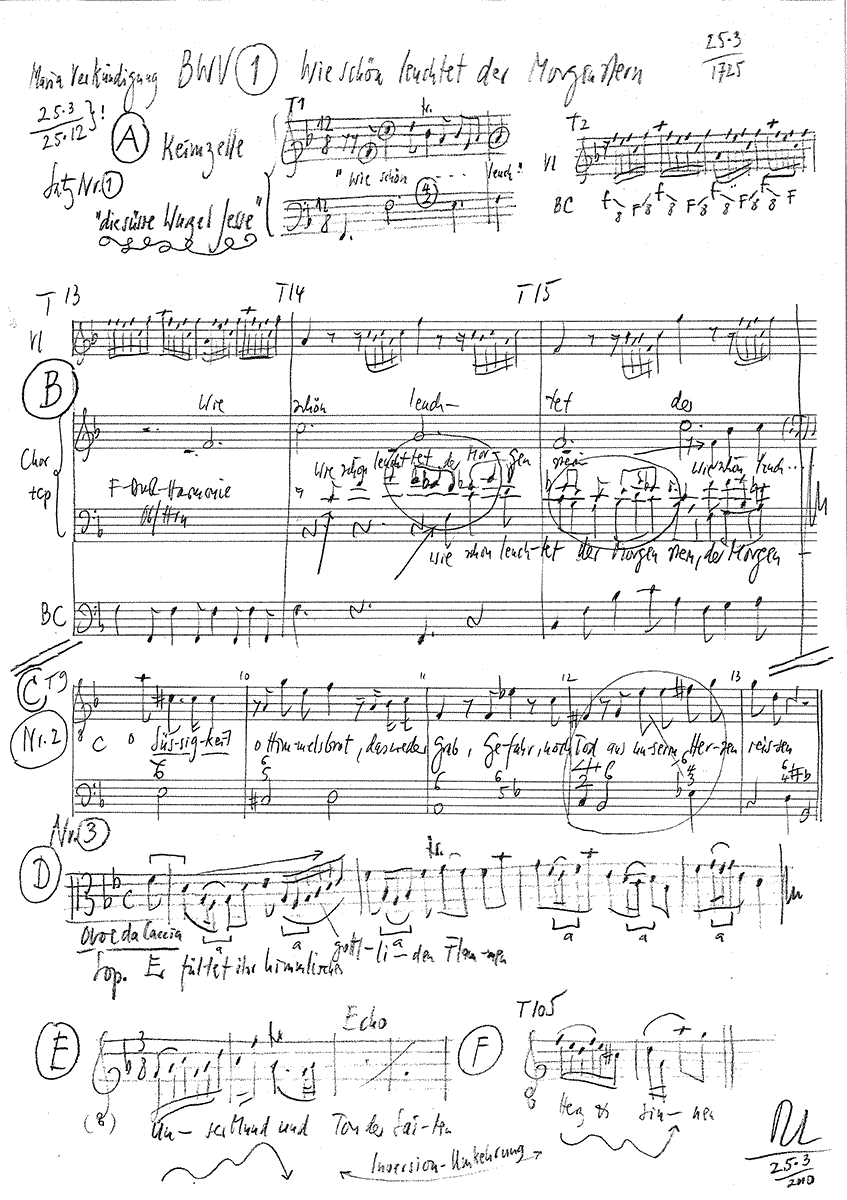

The cantata “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” (How beauteous beams the morning star), written for the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1725, completes Bach’s chorale cantata cycle of 1724. As it was the first work featured in the inaugural version of the Complete Works of Bach in 1851, it was later given the number BWV 1. The orchestration of this cantata is particularly exquisite: aside from four voices and the obligatory strings, it includes two concertante violins, two oboes da caccia and two horns – three uncommon pairings of solo instruments. The addition of brass instruments, however, was not necessarily unconventional for the orchestration of a celebratory hymn – Bach’s predecessor in Leipzig, Johann Kuhnau, also composed a “morning star” cantata with two obbligato horns.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Mirjam Berli, Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Sohn, Noëmi Tran Rediger

Alto

Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Damaris Nussbaumer, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Philippe Rayot, Oliver Rudin, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Plamena Nikitassova, Martin Korrodi, Christoph Rudolf, Ildiko Sajgo, Olivia Schenkel, Fanny Tschanz, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Oboe da caccia

Kerstin Kramp, Ingo Müller

Corno

Olivier Picon, Ella Vala Armansdottir

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Harpsichord

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Elisabeth Bronfen

Recording & editing

Recording date

03/26/2010

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 6

Philipp Nicolai, 1599

Text No. 2–5

Arranger unknown

First performance

The Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary,

25 March 1725

In-depth analysis

The opening choir, whose character sets the tone for the entire work, makes both effective and sensitive use of the rich orchestration. Written in a swaying 12⁄8 time, the concertante violins – effectively capturing the essence of the shining morning star – provide a decidedly gentle and decorative introduction. Inspired by the first lines of the chorale, their dance-like motif pervades the development of the entire movement. In the process, the individual instruments are not restricted to their own idiomatic material; instead, the various motifs roam through the entire orchestra – the typical long tones of the horns, for example, are first heard in the strings. In keeping with his approach for chorale cantatas, Bach weaves the lines of the hymn into this soundscape, intertwining the soprano melody with particularly imaginative pre-imitation in the lower voices. The obvious shift in the verse upon the words “lovely, kindly” is underscored by a change in the musical structure. Here, the initial chordal construction passes over to hymn-like rising figures that beautifully express the closing line “high and most richly exalted”.

Following this movement of heavenly sphere and peace is an equally enchanting recitative that textually bridges the events between the Annunciation and Christmas. The ensuing aria, an elegantly flowing movement, features a solo soprano voice over a pizzicato bass – the contrasting use of these two extreme registers is particularly striking. The addition of an oboe da caccia lends the movement a singularly intimate character, its warm and mellow tone translating perfectly the textual “flames both celestial and divine” that blaze only in the hearts of the faithful.

After the joyful and open-minded atmosphere of the bass recitative, the tenor aria, composed in a minuet-like 12⁄8 time, is reminiscent of a final movement of a double concerto for two violins and orchestra. The scoring for strings and voice is hardly surprising considering the wording of the text: “let our voice and strings resound”. Here, the tenor voice functions more as a third concertante part than as a soloist, and it is only in the extended middle section which speaks of “bringing honour with song” that the tenor voice comes clearly to the fore.

In the closing chorale, the sixth verse of Philipp Nicolais’s famous hymn from 1599, both horns figure again prominently. While the first horn doubles the soprano voice, the second horn sounds a magnificent countermotif – fittingly jubilant for the cantata’s finale.

Libretto

1. Chor

Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern

voll Gnad und Wahrheit von dem Herrn,

die süsse Wurzel Jesse.

Du Sohn David aus Jakobs Stamm,

mein König und mein Bräutigam,

hast mir mein Herz besessen,

lieblich, freundlich,

schön und herrlich, gross und ehrlich,

reich von Gaben,

hoch und sehr prächtig erhaben.

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Du wahrer Gottes und Marien Sohn,

du König derer Auserwählten,

wie süss ist uns dies Lebenswort,

nach dem die ersten Väter schon

so Jahr’ als Tage zählten,

das Gabriel mit Freuden dort

in Bethlehem verheissen;

o Süssigkeit, o Himmelbrot,

das weder Grab, Gefahr noch Tod

aus unsern Herzen reissen!

3. Arie (Sopran)

Erfüllet, ihr himmlischen, göttlichen Flammen,

die nach euch verlangende gläubige Brust!

Die Seelen empfinden die kräftigsten Triebe

der brünstigsten Liebe

und schmecken auf Erden die himmlische Lust.

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

Ein ird’scher Glanz, ein leiblich Licht

rührt meine Seele nicht;

ein Freudenschein ist mir von Gott entstanden,

denn ein vollkommnes Gut,

des Heilands Leib und Blut,

ist zur Erquickung da.

So muss uns ja

der überreiche Segen,

der uns von Ewigkeit bestimmt

und unser Glaube zu sich nimmt,

zum Dank und Preis bewegen.

5. Arie (Tenor)

Unser Mund und Ton der Saiten

sollen dir

für und für

Dank und Opfer zubereiten.

Herz und Sinnen sind erhoben,

lebenslang

mit Gesang,

grosser König, dich zu loben.

6. Choral

Wie bin ich doch so herzlich froh,

dass mein Schatz ist das A und O,

der Anfang und das Ende;

er wird mich doch zu seinem Preis

aufnehmen in das paradeis,

des klopf ich in die Hände.

Amen!

Amen!

Komm, du schöne Freudenkrone, bleib nicht lange,

deiner wart ich mit Verlangen.

Elisabeth Bronfen

“Twilight of the Soul”

Cultural-philosophical reflections on the cantata “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern”.

“How beautifully the morning star shines / full of grace and truth from the Lord, / the sweet root of Jesse.” So begins the Bach cantata on which I would like to develop some cultural-philosophical reflections. These deliberately lead a little away from biblical-theological thinking, but not too far, I hope. The morning praised by the cantata refers to the proclamation of the birth of Christ, thus representing a new beginning linked to the fulfilment of a promise. Thus, this morning star illuminates a day that is tantamount to a teleological promise, the longed-for redemption of humanity at the end of world history. My own work on how the night in Western culture is a privileged period for transgressing boundaries, which in a spiritual as well as moral sense signifies a transformation and at the same time a transmutation, ties in with the notion of a promising morning in two ways. It takes night for one to step into a morning; more precisely, it takes a spiritual derangement for the morning star to become the symbol of a spiritual dawn, a new dawn. With increasing secularisation, this idea is indeed conceived by our Western culture against the background of salvation history, but at the same time our modern morning star no longer brings its predetermined goal of an apocalyptic redemption of the world to the fore. It illuminates much more individualised stories of a new day.

At the same time, in the reconfiguration that the idea of an auspicious dawn has undergone in the Western pictorial repertoire, it is significant that the decisive passages of Christ’s life and passion receive their explosiveness against a nocturnal background and the spiritual darkness that corresponds to it. Coming into the world at night, Christ embodies a light prepared by God “to illuminate the sufferings, and to the praise of your people” (Luke 2:32). His worship is not only linked to repeated dream visions. The Passion of Jesus Christ also uses nocturnal scenes to dramaturgically underline the promise of a redemption from the world that will arise from the sacrifice of God’s Son: the Last Supper, the waiting in the Garden of Gethsemane, the descent from the cross and entombment, the resurrection. As the “other sun”, Christ brings light into the earthly night, illuminating both the despair of the believer and the betrayal of the doubter. Especially in painting, visual emphasis is repeatedly placed on this: The figure of Christ literally gives a light in the dark with his body, in order to invalidate with this “other light” the seduction emanating from demonic forces. From the end of the Passion story – and this is my point – we can say of the morning star and the light with which it illuminates the world anew: this star picks up a spiritual light which already illuminated the struggle between good and evil forces in the night. It continues this light, carries it over into a new day.

So how does my proposed figure of thought appear in the secularised thinking of modernity, that it takes the counter-period of night for the dawn to be significant? In my exploration of literary and visual night scenes, I have come across a wholly unexpected finding. That the night provides a stage for erotic excesses, forbidden adventures and violent assaults, as for all actions in general that one wants to ascribe to the demonic, is just as obvious as the fact that the night represents leisure and thus a liberation from the constraints of everyday life. What only becomes clear on closer inspection, however, is that, as is often the case in literary texts that deal with a spiritual or emotional awakening in the ethical sense, the night becomes the stage for self-questioning and self-questioning. In the night, the course is set that determines, on the one hand, who will enter a new day and who must remain in the night – madness, death – and, on the other hand, how the new day illuminated by a morning star might proceed. This is why the American philosopher Stanley Cavell also uses dawn as a symbol for a knowledge that can be gained during the night but must be forgotten again piecemeal upon awakening. In English, dawn means “morning” and is thus phonetically equivalent to the term for mourning. This leads to the following dictum for Cavell: The acquisition of knowledge leads to a mourning for all that one has to strip away in order to achieve a new beginning in the soul, like a new start into a morning. In other words: If one detaches oneself from cherished qualities and obsessions, which are therefore to be described as nocturnal because they are tantamount to an (albeit understandable) delusion, this step is to be understood as a dawning of the soul in the emphatic sense.

This train of thought is dramaturgically implemented in early modern times by Shakespeare, who has his lovers wake up at the edge of the fairy forest, illuminated by the morning star. The confusions of the previous summer night can only be remembered in a chimerical way. Nevertheless, these have contributed to the real lovers finding their way back to each other. At the height of modernity, in Arthur Schnitzler’s “Dream Novella”, the morning star at the end of the night is already a good deal gloomier. After a long wandering on the nocturnal streets of Vienna, which have led him from hysterical daughters and syphilis-stricken prostitutes to a secret orgy and finally to the morgue, Fridolin returns to his wife in the marital bed and finally confesses everything to her. As the morning star casts its light through the curtains of the bedchamber, the despairing husband bends to Albertine’s big bright eyes, “in which the morning now also seemed to rise”. The promise she announces to him is a sobering one. One can, she explains to the despairing Fridolin, “be grateful to fate (…) that we have escaped unscathed from all our adventures – from the real ones and from the dreamed ones”. To this she adds the assurance that “now we are well awake … for long”, but before Fridolin can add the word “for ever”, she herself limits the light of the morning star: “Never ask into the future.”

In the course of secularised modernity, as I had already indicated, the teleological ray of the morning star is weakened. Not in the literal fulfilment of a prophecy, but in a radically indeterminate, open future lies the hope of this dawn. Thus the last sentence of Schnitzler’s novella reads: “So the two lay in silence (…) until, as every morning at seven o’clock, there was a knock at the bedroom door, and (…) with a triumphant ray of light through the curtain gap and a bright child’s laughter from next door, the new day began.” Sobering and inspiring at the same time is this bourgeois-modern transcription of biblical thought. These figures – stand-ins for us – need a journey to the end of the night to come to the realisation that will allow them to change their lives. Detached from the references of everyday life, they can think of themselves anew. The morning star that illuminates their awakening is thus not only symbolic of the fact that they can wake up from all dream novellas. No matter how urgent the experience of this other knowledge may be, one must – and this is just as crucial – wake up at the end of the night. This modern morning star is emblematic of a necessity, even if not quite as teleologically conceived as the one from Bach’s cantata.

In order to bring this double movement once again to a concise image, which assigns a hinge function to the morning star, I would like to call on literature one last time, namely a scene from George Eliot’s grandiose social novel “Middlemarch”. Its heroine Dorothea, who likes to think of herself as a modern Saint Theresa, has spent the night in a state of mystical strife with herself and her God. At first, distraught over her lover’s supposed unfaithfulness, she had once again called up images of her failure before her inner eye. An accusation by others finally led to a salutary realisation – and that is why we speak here of that nightly enlightenment – which set the course for the coming day, both morally and spiritually. Dorothea realises that she has to abandon her selfish interests in order to assess her world more adequately by including all others who are also involved in her life world.

In the sense of the enlightenment that the light of Christ brings to a nocturnal mental struggle, this self-distance represents a redemption from her mental torment. With this thoroughly personalised promise, Eliot’s heroine falls asleep and wakes up at dawn with the question on her lips of how to act, now, today already. In this morning light, she goes to the window. Her gaze falls on a modern Holy Family: “On the country road was a man with a bundle on his back and a woman carrying her infant, in the field she saw moving figures – perhaps the shepherd with his dog. Far away in the stretched sky was the mother-of-pearl light; and she felt the greatness of the world and the manifold awakening of men to labour and endurance. She herself was a part of this random, pulsating life, and could neither gaze upon it as a mere spectator from her homely retreat, nor close her eyes to it in selfish lamentation.” The light of the morning star, with which a knowledge gained in the night can be carried over into a new day, makes a new day possible in the first place, this light provides the adequate correspondence for the still completely open decision to act. If the inspiring morning star takes up the light of a divine illumination in the night, then this beautiful glow is also the light by which those who are ready to step into a new day may orient themselves, even if one neither knows what this action will look like nor can calculate the consequences of this promise. One only knows that there has been a morning and that after every future night there will also be a new morning.

Literature

– Elisabeth Bronfen, Stanley Cavell. An Introduction, Hamburg 2009

– Elisabeth Bronfen, Thought Deeper than Day. A Cultural History of the Night, Munich 2008

– George Eliot, Middlemarch. Translated from the English by Ilse Leisi, Zurich 1962

– Arthur Schnitzler, Traumnovelle, in: Traumnovelle und andere Erzählungen, Frankfurt a. M. 1986

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).