Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit

BWV 106 // Funeral music

(God’s own time is the very finest time) «Actus tragicus», for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, recorders I+II, viola da gamba I+II and basso continuo

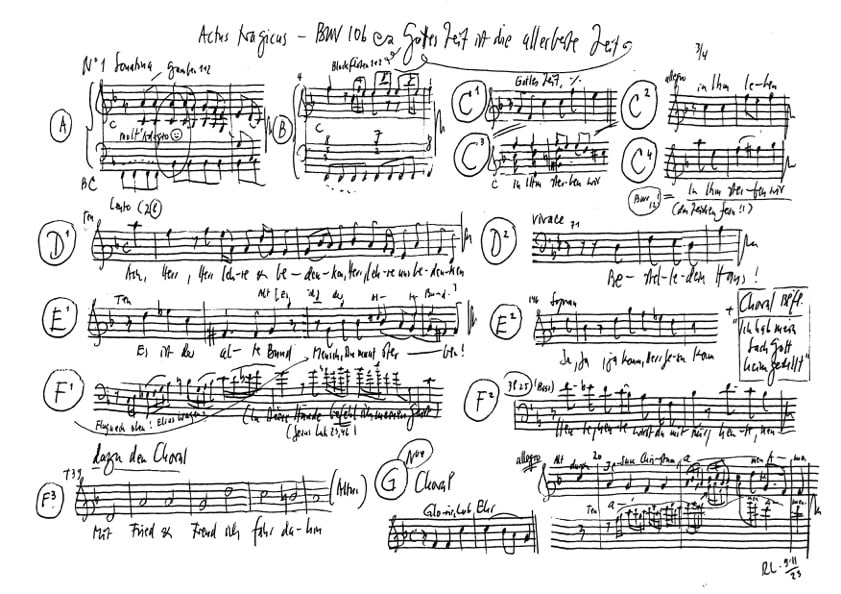

“Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” (God’s own time is the very finest time) was originally scheduled for performance on Friday 20 March 2020 in Speicher. Corona, however, put an abrupt end to all our plans, and instead that black Friday marked the start of a one-year concert sabbatical and a time of uncertainty for our organisation. In lieu of the cantata concert, our artistic director Rudolf Lutz performed as a one-man ensemble.

Introduction to cantata BWV 106 at the keyboard; an organ concert improvisation based on the “Actus Tragicus”

The reflective lecture for the cantata was to be held by our esteemed colleague Prof. Dr Ekkehart Reinelt from the foundation board of the International J. S. Bach Foundation Zurich; it had been his long-held wish to be the speaker for this specific work. In the meantime, he has unfortunately become too frail to perform this role.

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Bonus material

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violoncello

Bettina Messerschmidt

Viola da gamba

Rebeka Rusó, Martin Zeller

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Recorder

Annina Stahlberger, Teresa Hackel

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Theorbo

Fred Jacobs

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Luise Reddemann

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/11/2023

Recording location

Speicher AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

Unknown (possibly 10 August 1707

in Mühlhausen)

Texts

Acts 17:28 (movement 2.a); Psalm 90:12 (movement 2.b); Isaiah 38, 1 (movement 2.c); Johann Leon (movement 2.d); Luke 23:46 & Psalm 31:6 (movement 3.a); Luke 23:43 & Martin Luther (movement 3.b); Adam Reusner (movement 4)

In-depth analysis

Whether Albert Schweitzer truly would have foregone all of Bach’s other church cantatas for more works like the Actus tragicus is something he can no longer tell us. Nonetheless, his pointed remark speaks volumes about the composition’s appeal: although the instrumentation and form are uncommon in Bach’s mature sacred oeuvre, the work garnered an extraordinary amount of attention and appreciation upon its initial printing in 1830, also among the Mendelssohn Bartholdy family and their circle.

It was rather by chance, however, that “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” (God’s own time is the very finest time) ever became known in the music world. Indeed, the oldest surviving copy is dated 1768, and to this day, the exact composition period, purpose and pitch of the work remain unknown. Despite this uncertainty, however, the old-fashioned scoring featuring two recorders and two violas da gamba and the texts made up exclusively of Bible verses and a chorale suggest a funeral setting, hence the work’s posthumous nickname “Actus tragicus”. Researchers have suggested several possible dedicatees who died around 1707/08, for instance the Mühlhausen mayor Adolf Strecker or Bach’s uncle Tobias Lämmerhirt from Erfurt, but while such assumptions are feasible from a stylistic and historical perspective, they remain unproven. Whatever the exact occasion, Bach drew on the free, sacred concerto form to craft a moving contemplation on death and eternal life with multiple scene changes that provide scope for exploring all shades of grief, devotion and hope.

With gently circling flute figures and a continuo suggesting the tolling of bells, the opening sinfonia evokes the ideal image of a tranquil funeral procession. The first major section for the full ensemble then charts the way to our inevitable end: from the didactic opening words (“Gottes Zeit” – God’s time) to the diligently woven threads of life (“in ihm leben, weben und sind wir” – in him living, moving, we exist), on to the incisive finality of death (“in ihm sterben wir” – in him shall we die), an imploring plea (“ach Herr, lehre uns bedenken” – Ah, Lord, teach us to remember) and an irrefutable memento mori (“bestelle dein Haus” – set ready thine house). The extended fugue, with its abruptly descending head motif and relentlessly ticking continuo, then places the death of an individual in the context of a long, Old Testament genealogy (“Es ist der alte Bund” – This is the ancient law). Meanwhile, the comforting promise of the New Covenant is aptly anticipated by the instrumental chorale “Ich hab mein Sach Gott heimgestellt” (I have left all that concerns me up to God) and the soprano’s increasingly ecstatic words of assent that are sustained to the final breath (“Ja komm, Herr Jesu, komm” – Yes, come, Lord Jesus).

Opening the second major section, the alto solo “In deine Hände” (Into thine hands) leads the way to calmer pastures, with the continuo lines ascending heavenward and the open arc of the vocal gestures underscoring the readiness, freed of all earthly burdens, to entrust oneself to the “getreuer Gott” (faithful God). In the ensuing promise “Heute wirst Du mit mir im Paradies sein” (This day shalt thou with me in paradise be) sung by the bass and echoed in the imitations of the violas da gamba, the alto can then confidently weave in the Lutheran-Simeon hymn “Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin” (In peace and joy do I depart), with the singing strings offering an ever-so gentle accompaniment.

With the depths of pain and sorrow thus traversed, the final chorus emerges as a contemplative yet radiant song of praise. Although this movement, too, formally works through an early Reformation chorale verse (“In dich hab ich gehoffet, Herr” – In Thee, Lord, have I put my trust, 1533), the lively alternation of vocal quartet and instrumental lines transform the music into a setting of buoyant ease. Set as a virtuoso fugue, the final line “Durch Jesum Christum Amen” (Through Jesus Christ, Lord, Amen) lends the work’s conclusion a confident strength that may seem at odds with our modern understanding of timid piety but that, in truth, may reflect precisely the smiling, hopeful way we wish to be remembered by our loved ones.

Libretto

1. Sonatina

2.a Chor

Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit.

«In ihm leben, weben und sind wir,»

solange er will.

In ihm sterben wir zur rechter Zeit,

wenn er will.

2.b Arioso — Tenor

Ach, Herr, «lehre uns bedenken,

daß wir sterben müssen,

auf daß wir klug werden.»

2.c Arie — Bass

«Bestelle dein Haus; denn du wirst sterben

und nicht lebendig bleiben!

Bestelle dein Haus!»

2.d Chor — Sopran

Alt, Tenor, Bass

«Es ist der alte Bund:» Mensch, «du mußt sterben!»

Sopran

«Ja, komm, Herr Jesu!»

3.a Arie — Alt

«In deine Hände befehl ich meinen Geist;

du hast mich erlöset, Herr, du getreuer Gott.»

3.b Arioso — Bass; Choral

Bass

«Heute wirst du mit mir im Paradies sein.»

Alt

Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin in Gottes Willen,

getrost ist mir mein Herz und Sinn, sanft und stille,

wie Gott mir verheißen hat:

Der Tod ist mein Schlaf worden.

4. Chor

Glorie, Lob, Ehr und Herrlichkeit

sei dir, Gott Vater und Sohn bereit,

dem Heilgen Geist mit Namen!

Die göttlich Kraft

macht uns sieghaft

durch Jesum Christum, amen.

Luise Reddemann

Thank you very much for inviting me to speak to you here.

The cantata performed today has been with me for decades. I find it very comforting, precisely because it also acknowledges pain. It is considered a great masterpiece by a very young man, as Bach was just 22 years old when he wrote it. Not least because of his biography and the loss of both parents by the age of 10, the young Bach knew about grief and the need for consolation.

I am always enthusiastic about this cantata and delighted by the beautiful recorder sonatina at the beginning and the sung text:

“God’s time is the very best time. In him we live, weave and are as long as he wills. In him we die in due time, when he wills.”

I would like to refer to this passage here, followed by

“Oh Lord, teach us to remember that we must die so that we may become wise” from Psalm 90, i.e. ancient wisdom.

A young man can say that God’s time is the very best time and that God determines the right time for us to die. This young man was also wise. However, in his time people were generally more accepting of our mortality, or more precisely, they accepted this fact and did not suppress it as much as possible.

Nietzsche could recommend that a delicious, fragrant drop of frivolity could be added to every life precisely because of the certain prospect of death.

A delicious, fragrant drop of frivolity could undoubtedly do us good again at the moment. The art of living probably lies in practising acceptance of what happens to us. Unfortunately, we would rather imagine that we have control over almost everything. This is why I find the statement that God’s time is the very best time to be a wise and, for me, comforting statement that should not be underestimated. Because how often do we take ourselves and the things that affect us too seriously and too importantly and see too little of the big picture?

What does the cantata say to me? First of all, Bach’s recorders convey something playful and cheerful to me. It could be an invitation to discover life as a whole, even with pain, because of the realization of our finiteness, as Rose Ausländer describes it:

“Noch bist du da / Wirf deine Angst / in die Luft /” (from: Rose Ausländer: Gesammelte Werke, Bd. V: Ich höre das Herz des Oleanders, S.-Fischer-Verlag, Frankfurt a.M. 1995), an invitation to be aware of our finiteness and to encounter the life that is still there with an open heart.

Bertolt Brecht (1954 /1990, p. 1022) also commented indirectly on finiteness in his poem “Pleasures”, which can invite us to be open and grateful for the simple things in our lives and to appreciate them, such as: “The first look out of the window in the morning / The old book found again / Enthusiastic faces / … Old music / Comfortable shoes / Understanding / New music / Writing, plants / Traveling / Singing / Being friendly.”

These days, we could all be invited to use cheerfulness to take some of the weight off the difficult issues so that they don’t overwhelm us. We have no solutions for many things, but have to live with the difficult questions. Reflecting on the simple and friendly aspects of our lives could at least do us good in between.

Whatever the cantata “God’s time” may mean for individuals – I don’t want to and can’t interpret it theologically, there are more qualified people to do so – joy, hope and confidence always resonate. As a psychotherapist who helps many people who are under severe stress, it is particularly important to me to look at the whole of our lives. Suffering and joy are part of the whole of our lives and this is what the cantata conveys to me.

It is emphasized that this cantata must be a cantata of mourning. We don’t know exactly. If that is the case, then this young man Sebastian must have sensed that there is a path from mourning to confidence. And these are perhaps the most important messages for us: we cannot determine everything, especially not how much time we have on earth, and yet there is still reason for joy and confidence. And the cantata can be an invitation for us to reflect on this more, especially when things get difficult. And to be grateful for the friendly gifts of life that are already available, as Brecht’s poem points out. For me, the statements in the cantata and Brecht’s poem complement each other.

I would like to briefly refer here to an aria composed over 20 years later, namely “Wie will ich mich freuen, wie will ich mich laben” from the cantata “Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal”. In the time between these two cantatas, Bach had to go through much pain. I find it all the more remarkable that he repeatedly finds ways to find cheerfulness and serenity. In the later cantata 146, it says towards the end: “How will I rejoice, how will I refresh myself when all transient tribulation is over! Then I will shine like the stars and shine like the sun, no mourning, weeping or crying will disturb my heavenly bliss.”

In both cantatas, the solution lies, as was customary at the time, more in heaven, i.e. in the other dimension after death.

I would like to suggest that we allow ourselves to experience heaven at least once in a while, it is up to us whether we allow ourselves to do so.

It seems to me that one solution is for us to strive for kindness. Kindness with ourselves, kindness with loved ones, but also with distant ones and ultimately kindness with creation as a whole, which can be expressed in gratitude. The phrase “God’s time is the very best time” echoes this gratitude for me.

Life becomes easier when we are mindful of the many small and larger things in everyday life that are given to us by life and which are by no means a matter of course, and consciously perceive them with gratitude instead of taking them for granted. Small moments of joy and happiness can gain depth through gratitude. Gratitude thus becomes a helpful means of combating deficit orientation – not by glossing over things, but by taking a closer look and seeing and accepting life as a whole, with joyful moments alongside the difficult ones. Then, for example, it can become clear that it does you good to be grateful to people who give you a friendly smile and perhaps even smile back. Many good things are given to us by many people and non-human beings. Realizing this can make life richer and more valuable and open and widen the heart. Moving away from thinking exclusively in terms of lack and discovering abundance as a positive good has given many of my patients a new perspective on others and on life. We cannot exist without others and other things; becoming gratefully aware of this can become a source of joy and loving feelings.

However, it would be euphemistic to only hear that the cantata is about joy. In my view, it is about saying yes to the whole of our lives. So it is also and especially about saying yes to our finiteness.

We can ask ourselves how we deal with the fact that there is suffering that we cannot remove from our lives. And can we “send” ourselves into things? Or would we rather complain?

Are we ready to “praise” life/God or the beings to whom we owe joyful things, in the sense of joyful gratitude?

Are we ready, as Hilde Domin (1959/2022, p. 14) once described it,

to walk “- almost without fear – in time with our hearts, as if we were protected as long as love does not cease”?

For me, many of Bach’s cantatas are works that help me to walk again and again “almost without fear”, i.e. comforting promises.

So allow me to share a few thoughts on the current situation, inspired as a psychoanalyst by one of my important teachers:

The willingness to commit acts of war has increased almost exponentially in recent weeks. There is a letter from Sigmund Freud to Albert Einstein from 1932 in which Freud says that there is probably no way that people could get along without aggression; at best, he hoped, psychoanalysis would be able to contribute to more friendliness (Einstein & Freud, 1933, p. 53 f.). Today, the American psychoanalyst Donna Orange (2011, p. 50, 59) advocates compassion again and again, referring to the philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas (1991/1995, p. 138 f.), who often referred to the phrase “after you” – après vous – as an impressive and simple reminder that we should give way to others.

When I refer to Bach’s early cantata, I hope that more and more people will be found who do not deny their aggression and anger, but who try to take more respectful paths instead of threatening others with death or even killing them, i.e. who are prepared to focus more on what we have in common as human beings, to accept suffering as a constant of human life and not to forget cheerfulness, which is also echoed in the cantata.

Here in Switzerland, you have managed to live without war and without participating in wars for centuries. I ask you to speak up and point out that it is possible to live without waging war. Which does not necessarily mean that you have to give in. Please take what you know about peaceableness and willingness to compromise into the world, not least because we can all know that there is greater than self-centeredness. This cantata can invite us to do so.

Literature

Brecht, Bertolt (1990): Amusements. In: Bertolt Brecht, Collected Works, vol. 10: Poems. (3rd unedited reprint; p. 1022). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp (originally published in 1954).

Domin, Hilde (2022): Balance. In: Hilde Domin, Sämtliche Gedichte (5th, uned. ed.; p. 14). Frankfurt: Fischer (originally published in 1959).

Einstein, Albert & Freud, Sigmund (1933): Why war? Paris: International Institute for Intellectual Cooperation.

Lévinas, Emmanuel (1995): Between us. Versuche über das Denken an den Anderen (Series: Edition Akzente). Munich: Hanser (French original published 1991).

Orange, Donna M. (2011): The Suffering Stranger. Hermeneutics for Everyday Clinical Practice. New York: Routledge.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).