Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden

BWV 1083 // Unspecified occasion

(Lord, annul all my transgressions) for soprano and alto, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sonoko Asabuki, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Frank Urbaniok

Recording & editing

Recording date

22/11/2024

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Kirche St. Laurenzen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

Period of composition

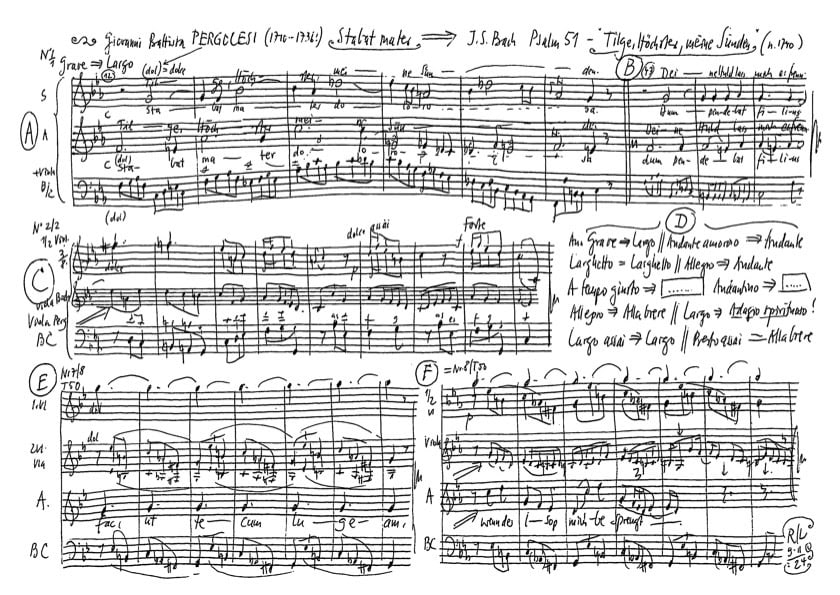

Approx. 1746–1747, arrangement of «Stabat mater» by G. B. Pergolesi

Text

Adaptation of psalm 51, poet unknown

Libretto

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi:

«Stabat mater» Nr. 1 & 12

Wortnahe und unrhythmische Übersetzung von Fr. Gregor Baumhof, OSB

Nr. 1

Stabat mater dolorosa,

iuxta crucem lacrimosa,

dum pendebat filius.

Nr. 12

Quando corpus morietur

fac ut animae donetur

paradisi gloria.

Amen.

Johann Sebastian Bach:

BWV 1083 «Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden»

Versus 1 — Sopran, Alt

Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden,

deinen Eifer laß verschwinden,

laß mich deine Huld erfreun.

Versus 2 — Sopran

Ist mein Herz in Missetaten

und in große Schuld geraten,

wasch es selber, mach es rein.

Versus 3 — Sopran, Alt

Missetaten, die mich drücken,

muß ich mir itzt selbst aufrücken;

Vater, ich bin nicht gerecht.

Versus 4 — Alt

Dich erzürnt mein Tun und Lassen,

meinen Wandel mußt du hassen,

weil die Sünde mich geschwächt.

Versus 5 — Sopran, Alt

Wer wird seine Schuld verneinen

oder gar gerecht erscheinen?

Ich bin doch ein Sündenknecht.

Wer wird, Herr, dein Urteil mindern

oder deinen Ausspruch hindern?

Du bist recht, dein Wort ist recht.

Versus 6 — Sopran, Alt

Sieh, ich bin in Sünd empfangen,

Sünde wurde ja begangen,

da wo ich erzeuget ward.

Versus 7 — Sopran

Sieh, du willst die Wahrheit haben,

die geheimen Weisheitsgaben

hast du selbst mir offenbart.

Versus 8 — Alt

Wasche mich doch rein von Sünden,

daß kein Makel mehr zu finden,

wenn der Isop mich besprengt.

Versus 9 — Sopran, Alt

Laß mich Freud und Wonne spüren,

daß die Beine triumphieren,

da dein Kreuz mich hart gedrängt.

Versus 10 — Sopran, Alt

Schaue nicht auf meine Sünden,

tilge sie, laß sie verschwinden,

Geist und Herze schaffe neu.

Stoß mich nicht von deinen Augen,

und soll fort mein Wandel taugen,

o, so steh dein Geist mir bei.

Gib, o Höchster, Trost ins Herze,

heile wieder nach dem Schmerze,

Es enthalte mich dein Geist.

Denn ich will die Sünder lehren,

daß sie sich zu dir bekehren

und nicht tun, was Sünde heißt.

Laß, o Tilger, meiner Sünden,

alle Blutschuld gar verschwinden,

daß mein Loblied, Herr, dich ehrt.

Versus 11 — Alt

Öffne Lippen, Mund und Seele,

daß ich deinen Ruhm erzähle,

der alleine dir gehört.

Versus 12 — Sopran, Alt

Denn du willst kein Opfer haben,

sonsten brächt ich meine Gaben,

Rauch und Brand gefällt dir nicht.

Herz und Geist, voll Angst und Grämen,

wirst du, Höchster, nicht beschämen,

weil dir das dein Herze bricht.

Versus 13 — Sopran, Alt

Laß dein Zion blühend dauern,

baue die verfallnen Mauern,

alsdann opfern wir erfreut;

alsdann soll dein Ruhm erschallen,

alsdann werden dir gefallen

Opfer der Gerechtigkeit.

Versus 14 — Sopran, Alt

Amen.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Reflection on BWV 1083

Frank Urbaniok

Bach’s cantata is a haunting plea, presented in a slightly oppressive manner. The sinner, burdened with guilt for his misdeeds, begs God for forgiveness: ‘Tilge, Höchster, meine Sünden’ (Most High, blot out my sins).

Guilt, atonement and forgiveness are topics that have occupied people for thousands of years. Guilt is the starting point to which atonement and forgiveness relate. Atonement is, not always, but often a punishment. It is therefore a reaction to guilt. Forgiveness seeks to wipe out the guilt, to eliminate it from the world. Based on this context, it makes sense to first deal with the starting point. So what is guilt?

Two forms of guilt

Guilt comes in two forms. One form is a kind of measuring system. It assesses how serious the offence is. The more serious it is, the greater the guilt. A person has been killed. The court’s job is to find out whether the defendant is guilty and, if so, how serious his guilt is. The severity of the guilt determines the punishment. In the case of a deliberate killing, it is a minimum of five and a maximum of twenty years, depending on how serious the guilt of the perpetrator is.

The other form of guilt is the feeling of guilt. Because it is a feeling, it is highly subjective. There are psychopaths who commit the most horrific crimes. But they don’t lose any sleep over it. Because they don’t feel guilt. Then there are people who have done nothing at all. Nevertheless, they are plagued by a feeling of severe guilt. This can be a symptom of a mental illness, such as a severe depression. The person has done nothing. Yet they feel guilty, and this feeling of guilt can be very tormenting.

Guilt as a business model

It is to the Catholic Church’s credit that it discovered that feelings of guilt are an excellent tool for controlling or even oppressing people. After all, I cannot escape the feeling of guilt that I carry within me. If we succeed in setting up very rigid moral rules in which human nature is bound to become entangled, then many people will walk around with a feeling of guilt. People with feelings of guilt do not rebel, they comply. If you now promise these people to free them from their feelings of guilt, at least temporarily, then that is a perfect business model. Even before a person is born, their account is already debited with original sin. What does the cantata say? ‘See! I am conceived in sin, sin was indeed committed, where I was generated.’

So, humans are already born with guilt. And the only instance that can alleviate this sense of guilt and make it easier for humans is the same instance that permanently reminds them – or should one say, constantly talks them into – having incurred guilt. By submitting and obeying, humans are offered the prospect of reducing their guilt through forgiveness.

The evolutionary meaning of feelings of guilt

We might ask ourselves why we have feelings of guilt at all. What are they good for? As so often, evolution provides the answer. Evolution is not about God, religion, human rights, truth or other highly respected values. It only recognises one currency: improving the ability of the species to survive. So, over millions of years, evolution is constantly looking for improvements that enable one species to have a better chance of survival in competition with other living beings. No more and no less.

Evolution is humourless. It is never about great values or the individual. This can easily be illustrated by an example: rabbits. The evolutionary business model of rabbits is as follows: rabbits are primarily food for other animals that feed on them. Evolution has designed rabbits to reproduce faster than they are eaten. This shows what I mean by evolution being humourless. The only thing that counts is the survival of the species.

And why then do we need a sense of guilt? To answer that, we have to understand how Homo sapiens, indeed how many living creatures on this planet, are constructed. There are two fundamental principles: selfish self-assertion on the one hand and the potential for cooperation on the other.

Selfish self-assertion is an irrepressible life energy and aggressive primal force. It is all about survival, asserting oneself and beating competitors out of the field. In its purest form, it is unscrupulous, uninhibited and boundless. The lion eats the cubs of its predecessor so that its genes can assert themselves without competition. It’s not a nice character trait, but the principle of selfish self-assertion is present to a greater or lesser extent in every living creature. Friedrich Nietzsche aptly called it the will to power. By this he meant that an irrepressible, archaic and ultimately selfish driving force exists in every living creature.

The opposite principle is the potential for cooperation. This can also be seen everywhere in nature. There are schools of fish, prides of lions and herds of ungulates. Here, too, evolution pursues only one goal: the cooperation of individuals in a group increases their chances of survival compared to trying it alone. Cooperation thrives on relationships, bonds and empathy.

Evolution has invested in better teeth for the lion, in better poison for the snake and in better brains for Homo sapiens. This catapults both our selfish self-assertion and our potential for cooperation into previously unimagined dimensions. This is why we can wage horrific wars and destroy the foundations of our own existence, but also organise groups of millions of individuals.

Most people have a good balance of both principles. They have a healthy sense of self-interest and sufficient assertiveness to avoid falling by the wayside. But they can also cooperate and connect with others in work groups or private relationships.

However, there are also people for whom these principles are totally exaggerated individually. The already mentioned psychopaths, for example, are only interested in whether something is useful to them or not. So nothing with cooperation, but the enforcement of their own interests is at the expense of others. They embody the principle of selfish self-assertion at the expense of cooperation in its purest form. Their motto is: assert themselves and profit without regard for others. On the other hand, there are also people who have too much potential for cooperation. They are dependent, can no longer make their own decisions, always have to ask someone else and permanently subordinate themselves. These extremes show what these principles look like in their purest form. As I said, most people have them in a weaker form. Depending on the situation, one or the other is in the foreground.

When it comes to the potential for cooperation, guilt comes into play. Because cooperation with guilt works better than without guilt. That is why evolution has built it into us. When people feel responsible and feel guilty when they make mistakes, the group is more capable of surviving and therefore more successful. Evolution says: a group with individuals with a built-in sense of guilt works better than a bunch of uninhibited egoists. This is because the sense of guilt acts as a brake on the uninhibited pursuit of selfish self-assertion. In addition to guilt, there are other feelings with a similar function, such as shame or regret.

Forgiveness

And what about forgiveness? There are cultures where blood feuds cause much suffering over generations through revenge and counter-revenge. From an evolutionary point of view, it therefore makes sense to be able to resolve misconduct. In this context, forgiveness has two positive aspects in the case of crimes. It reduces the perpetrator’s sense of guilt and can help the victim to find peace again. That may well be. But perhaps it is impossible to ever draw a line under a very serious offence. In that case, it is unacceptable to try to influence victims to finally forgive the perpetrator just because all those not affected want to have an ideal world again.

The guilt and prevention principle

The second quality of guilt is guilt as a unit of measurement. The state’s monopoly on violence and punishment was a huge step forward for civilisation. Before that, people had to defend themselves and react when a family member was injured or killed. If punishment is not carried out by the state, arbitrariness and chaos are the result. But the state needed a yardstick to impose the punishments. We do not believe in an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Because of our Christian tradition, it made sense to choose guilt as a measuring system.

The guilt principle is always oriented towards the past. I ask: How serious is your guilt for what you did in the past?

Unlike the guilt principle, the prevention principle is directed towards the future. The question is not, what was your guilt in the past? The question now is, how dangerous is the offender likely to be in the future? In other words, how high is the risk that the offender will rape another woman or kill someone? For a long time, the rights of victims and the principle of prevention played no role in criminal law. This has only changed in the recent past. I have always believed that the principles of guilt and prevention must be balanced. Assessing the danger posed by a perpetrator is the key process for preventing crimes and protecting potential victims. Only if you know exactly how dangerous a perpetrator is, can you know which measures can be used to reduce that danger.

If someone threatens another person’s life, then from the point of view of guilt, this is not a serious crime with only a minor penalty. But the question of the severity of the guilt is unimportant here. The crucial question is: does the offender carry out his threat and commit a homicide? This example shows that the principle of prevention and the question of dangerousness are quite separate from the principle of guilt. This principle of prevention, which is about avoiding future crimes, is crucial for the safety of the population.

False accusations

I would now like to come to a conclusion. You have heard two short audio clips. They are about a woman who was wrongly sentenced to many years in prison due to a false accusation. False accusations are a completely different side of guilt. This is about people who have done nothing, but who are nevertheless accused of an offence and unfortunately often convicted. This is terrible, and these people are victims. Due to various social developments, false accusations are on the rise. This is an issue that is still under the radar in public, the media and the judiciary and is not yet sufficiently recognised. It is true that the credibility of victims should not be generally questioned. However, this does not mean that the statements of alleged victims should be accepted uncritically. Unfortunately, however, this is happening more and more often today, according to the motto: victims are always right. In this social trend, however, there are an increasing number of freeloaders who abuse this, and that is why false accusations are on the rise. Victims of such false accusations have so far had no lobby and are socially stigmatised.