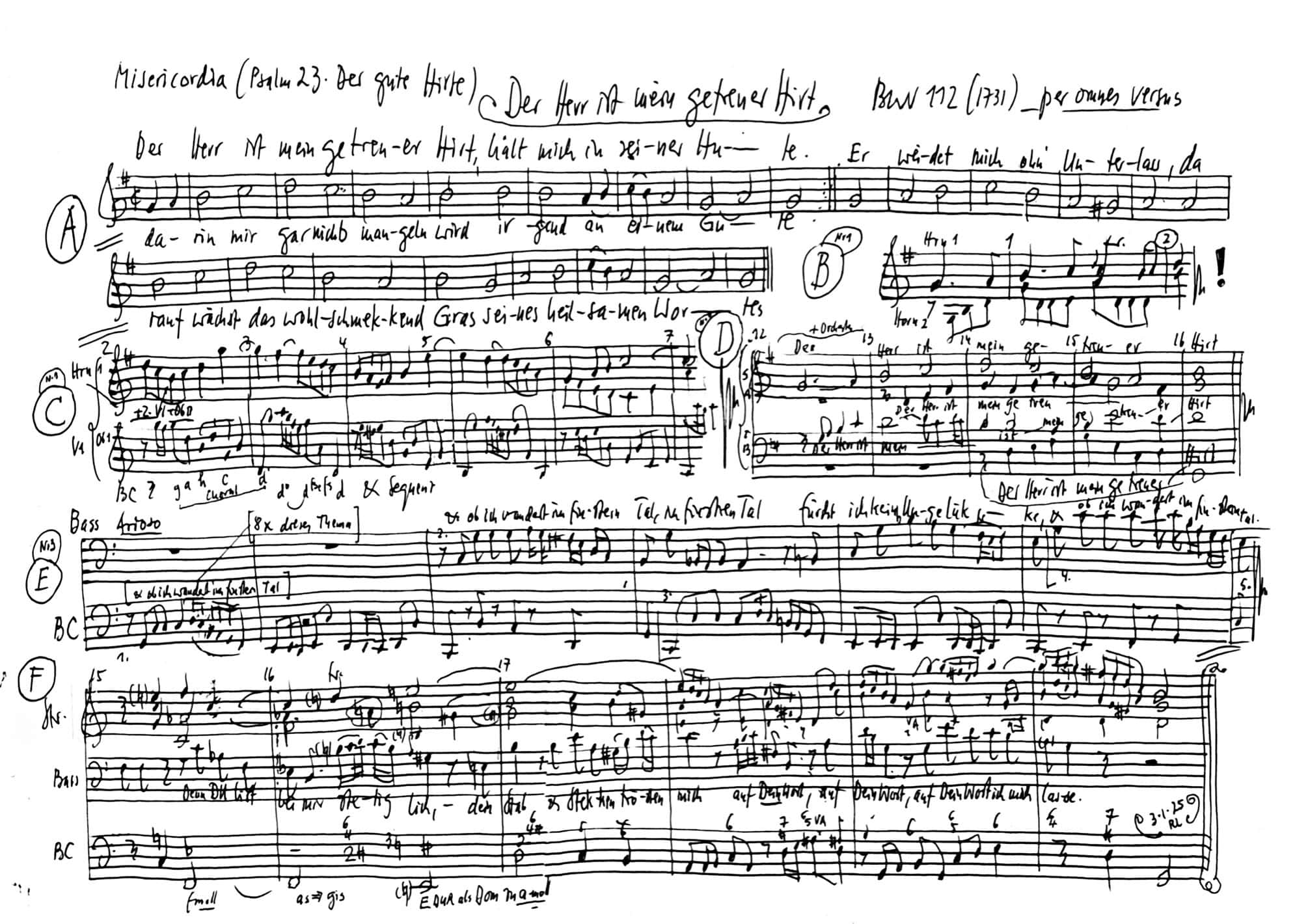

Der Herr ist mein getreuer Hirt

BWV 112 // For Misericordias Domini (Second Sunday after Easter)

(The Lord is now my shepherd true) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn I+II, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Choir

Soprano

Alice Borciani, Cornelia Fahrion, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Anne Bierwirth, Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Laura Kull, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Tobias Mäthger, Tiago Oliveira, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen

Viola

Martina Bischof, Lucile Chionchini, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Linda Alijaj, Mei Kamikawa

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Horn

Stephan Katte, Thomas Friedlaender

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Béatrice Acklin

Recording & editing

Recording date

21/01/2025

Recording location

Trogen (AR) // Evang. Kirche Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

8 April 1731, Leipzig

Text

Based on Psalm 23, poet unknown

Libretto

1. Chor

Versus 1

Der Herr ist mein getreuer Hirt,

hält mich in seiner Hute,

darin mir gar nichts mangeln wird

irgend an einem Gute.

Er weidet mich ohn Unterlaß,

darauf wächst das wohlschmeckend Gras

seines heilsamen Wortes.

2. Arie – Alt

Versus 2

Zum reinen Wasser er mich weist,

das mich erquicken tue.

Das ist sein fronheiliger Geist,

der macht mich wohlgemute.

Er führet mich auf rechter Straß

seiner Geboten ohn Ablaß

von wegen seines Namens willen.

3. Rezitativ – Bass

Versus 3

Und ob ich wandert im finstern Tal,

fürcht ich kein Ungelücke

in Verfolgung, Leiden, Trübsal

und dieser Welte Tücke:

denn du bist bei mir stetiglich,

dein Stab und Stecken trösten mich,

auf dein Wort ich mich lasse.

4. Arie – Duett Sopran und Tenor

Versus 4

Du bereitest für mir einen Tisch

für mein’ Feinden allenthalben,

machst mein Herze unverzagt und frisch,

mein Haupt tust du mir salben

mit deinem Geist, der Freuden Öl,

und schenkest voll ein meiner Seel

deiner geistlichen Freuden.

5. Choral

Versus ultimus

Gutes und die Barmherzigkeit

folgen mir nach im Leben,

und ich werd bleiben allezeit

im Haus des Herren eben,

auf Erd in christlicher Gemein,

und nach dem Tod da werd ich sein

bei Christo, meinem Herren

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com)

J. S. Bach Foundation – Reflection on the cantata: ‘The Lord is my faithful shepherd’

by Béatrice Acklin

‘The Lord is my faithful shepherd’ – a shepherd? Possibly even with sheepdogs to bark at those who stray? Doesn’t the image of a shepherd bypass what makes humans special, namely our ability to determine what we do and which path we take? Doesn’t the image of a shepherd smack of the masses and the collective, of pushing and shoving, of herd animals and bellwethers, while we as modern people place particular value on unique and distinctive life plans and outstanding biographies?

The point of the psalm ‘The Lord is my shepherd’ is not, of course, to ignore human freedom, but to ask: on whom does a person orientate themselves when they shape their lives and go their own way? However great our freedom to determine our own lives may be, it is difficult for us to find orientation within ourselves; it must come from outside. Or, to stay with the image: we are incapable of being our own shepherd.

We come into the world unasked, and we leave unwillingly. What is possible in between depends on many factors, most of which are beyond our control. The scope for shaping our lives shrinks to nothing in the end. Even the results of our self-determined actions or omissions are then taken out of our hands. Sandwiched between a beginning and an end, life raises the question of what our bearings are, especially when we run into difficulties.

For the person praying Psalm 23, as the cantata text suggests, the point of orientation seems clear. The four-hundred-year-old text reads:

‘And though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death

I will fear no evil

For you are with me

Your rod and your staff, they comfort me

On your word I rely.’

What gives the person praying orientation is not looking at themselves – and certainly not at political pied pipers who make promises of salvation of all kinds. What gives the person praying in the psalm orientation is looking at him, whom Jews, Christians and Muslims call the “Most Merciful” and who is described by Kafka as a “light-filled abyss”.

The words of the person praying, whose ‘reliance’ on God’s word also holds true ‘in the dark valley’, express a trust in God that is probably alien to most modern people – these ‘orientation orphans’, as Hermann Lübbe says.

On 1 November 1755, All Saints’ Day, when thousands of believers were crowding into the churches of Lisbon to attend mass, the city was hit by a strong earthquake shortly before 10 o’clock. Churches and other buildings collapsed and buried countless victims under their debris. The candles lit in honour of the saints fell to the ground and set entire districts on fire. The earthquake, which almost completely destroyed Lisbon and cost the lives of tens of thousands of people within a few minutes, shattered the trust in God and the world of an entire generation and left theologians in dire need of an explanation: How could a good and almighty God, on All Saints’ Day of all days, allow the faithful to die indiscriminately and cruelly? The age-old question of theodicy was posed with renewed urgency in Lisbon.

The question of how God can allow such blatant injustices also preoccupied the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. In his novel The Brothers Karamazov, he has one of his main characters, Ivan Karamazov, say the following: ‘I’m not talking about the sufferings of the great. They ate the apple from the Tree of Knowledge, to hell with them, but the children, the children. Why have they also become the fertiliser for God’s future heaven? This entry price is far too high for me. That is why I hasten to return my ticket to God.’ In the face of the unspeakable suffering of children and all their unrecognised tears, Ivan Karamazov wants nothing more to do with this God, he no longer trusts him and returns his ticket to heaven “with all due respect”.

While ‘trust in God’ was the actual basic form of trust for people of earlier times, the Enlightenment worked towards trusting in people as fundamentally good, reasonable and therefore reliable beings instead of trusting in God. However, this belief has not withstood reality. While it is true that trust in God may have largely been abandoned with the Enlightenment, trust in rational human beings has also proved fragile. As a risky advance, trust is a cheque on the future, which always carries the risk of disappointment. And as a network between people, trust only lasts until the first suspicion tears it apart.

Adele Raemer, a well-known blogger, regularly reported on life on the border and how she picked up sick people from the other side of the border and drove them to distant hospitals for treatment. In her blogs, she told of how, despite all political adversity, mutual trust grew and friendships developed across the border. On that Saturday morning of 7 October, when the unthinkable happened and she miraculously survived in her hiding place in the kibbutz, Adele Raemer received dozens of WhatsApp messages from friends in Gaza asking how she was doing. To this day, Adele Raemer says, she still doesn’t know whether they really wanted to know how she was doing – or whether they just wanted to find out where she was.

Where trust is damaged or betrayed, mistrust arises. Trust does not just disappear, but is increasingly permeated and absorbed by mistrust: the person whose trust is absorbed by mistrust soon sees nothing but rivals everywhere. Anyone who has lost their trust in those in government will soon suspect conspiracies everywhere. And if you are the head of government who has to ask for a vote of confidence, it’s likely to be the end of the road for you.

We all live with trust, and without trust we would not be able to get out of bed in the morning, said the sociologist Niklas Luhmann. Nevertheless, trust is not something that can be acquired. Like all the important things in life – decisive encounters, love, friendship – trust is not available, it cannot be summarised in Excel spreadsheets. Trust does not come about as a result of planning; we cannot manufacture it ourselves, we can only give it. Trust has to do with not-knowing, it contains elements that transcend reason.

This is where the field of religion opens up: in religions, trust is the foundation and is called faith. In the Christian tradition, faith and trust are often interwoven to the point of being indistinguishable. Faith is described as relying on, as trusting in God – in something greater than ourselves.

Unlike people in the modern world, people in the past whose world view extended beyond the rational did not abandon their trust in God despite contrasting experiences. They suffered because of God, because of his darkness, his absence, his silence, his incomprehensibility, but none of this prevented them from trusting him despite everything, from relying on him existentially. They held on to God and continued to seek him even where everything actually spoke against God.

An impressive example of this is the story of Job:

It tells of God and the devil meeting to discuss Job. The devil claims that Job is only a believer because he is rich and has no other reason to complain – and he bets that Job will turn away from God as soon as suffering befalls him. God takes up the wager. Thereupon, one misfortune after another befalls Job: everything is taken from him, including his own health, family, possessions, land, and friends. But Job does not turn away from God. He cries out and accuses God, asking Him again and again what he has done to deserve this. But he does not let go of him and continues to place his trust in him. In the end, the devil has to admit defeat and Job – or so the story goes – receives back what he had lost, double and triple.

The person praying in Psalm 23, probably the most famous psalm in the Bible, also clings to God despite or precisely in the face of all the adversities of life. At the beginning, he speaks of God as the shepherd in the third person. He does not speak to God, but about him, as theologians tend to do. Then suddenly the ‘he’ becomes a ‘you’, a counterpart. An austere theological sentence becomes an intimate prayer.

Faith may no longer be able to move mountains, but modernity has also grown old: two world wars, totalitarian catastrophes and the global helplessness in the face of a tiny virus present a balance sheet that does little to strengthen confidence in reason. It seems as if the Enlightenment, too, has exhausted itself, as if its arguments, too, lack the depth of conviction. Particularly in disorienting and bleak times, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s ‘feeling of absolute dependence’ may be more familiar to many an enlightened ‘despiser of religion’ than he would like. In the face of illness and death, in existential situations in which we become all too aware of our finite rationality and realise that, even as autonomous subjects, we do not owe our lives to ourselves – in such moments, the enlightened world view is hardly likely to help as a substitute for faith.

When the scream breaks, when our voice fails us, the lamenting and sighing, the simple melody and the lament of Bach’s cantatas, which contain every conceivable human feeling, envelop the wounded soul like a protective cloak. When we are lost for words, the psalmists, these ancient biblical poets, lend us words of lament and questioning, of consolation and hope. And if our trust in God – ‘the immortal rumor’, as Robert Spaemann called it – if our trust in God is about to take flight, then we can find someone in the psalmist of Psalm 23 who will support our faith, which has long since ceased to be arrogant and is now only fickle.

Perhaps the trust expressed in Psalm 23 is like rowing: we go through life trusting, not like walkers, who have the past behind them and the future ahead of them. Rather, we row with the future behind us and the past before us. The longer we row, the more landscape spreads out before our eyes. It is only when we look back that we recognise how individual pieces of the puzzle of our lives fit together and make sense.