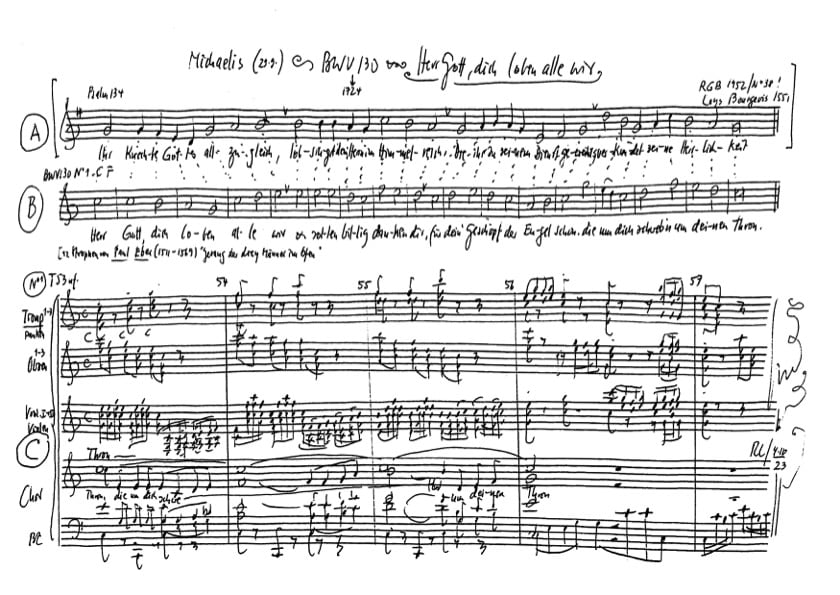

Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir

BWV 130 // Feast of St Michael and All Angels

(Lord God, we praise thee every one) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpets I–III, timpani, transverse flute, oboe I–III, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Stephanie Pfeffer, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Antonia Frey, Laura Kull, Alexandra Rawohl, Simon Savoy, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Sören Richter, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Simón Millán, Julian Redlin, Peter Strömberg, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Elisabeth Kohler, Aliza Vicente, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Clara Espinosa Encinas, Laura Alvarado

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Jaroslav Rouček, Karel Mnuk, Pavel Janeček

Timpani

Martin Homann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Walter Sparn

Recording & editing

Recording date

27/10/2023

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Composer of chorale interlude, chorale No. 6 “Darum wir billig loben dich”

Thomas Leininger

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

29 September 1724, Leipzig

Text sources

Paul Eber (movements 1, 6); unknown (movements 2–5)

In-depth analysis

The introductory chorus to the cantata “Herr Gott, dich loben wir alle” (Lord God, we praise thee every one, BWV 130) presents a striking reminder of why some chorales of the Reformation era were perceived as veritable battle songs. Indeed, this setting of Paul Eber’s hymn from 1561 is so strident in character that the work’s relationship to the Feast of St. Michael and the final War of Heaven waged by the angels against Satan is made audible from the very first bar, despite the fact that neither event is mentioned in the initial verse of the text. This celebratory music, which was performed on 29 September 1724 as part of Bach’s chorale cantata cycle, opens with exceptional force: fortified by the stable key of C major, three “army divisions” of trumpets plus timpani, three oboes, and strings try to outgun one other with loud fanfare volleys ere the orchestral barrage gives way to an alternating choral “cannonade” that blazes a trail for the triumphant soprano hymn melody accompanied by dynamic lower voices. In this captivating, rapidly unfolding setting, we sense just how much mobilising energy the Christian – and here distinctly Lutheran – declaration of faith was capable of releasing in Bach’s Pre-Enlightenment era. At the same time, we can distinguish the contours of a splendidly armed “Lord almighty”, who, in Bach’s times, was at least the equal of the “Prince of peace” we feel more attuned to today.

In the alto recitative, this grand hymn of praise gives way to an argumentative commentary that declares the radiance and assistance of the angels as proof of God’s devotion to humankind, thereby relating St. Michael’s victory in the Book of Revelation to the daily challenges facing Bach’s contemporaries. The winged attendants are then invoked with the attributes of wisdom and proximity to Christ ere the mention of Satan, marked by a devilish dissonance, provokes the renewed intervention of the “army divisions”. Accordingly, the bass aria “Der alte Drache brennt vor Neid” (The ancient serpent burns with spite) is scored in emblematic fashion for three trumpets and timpani, with the opening fanfares, drum rolls and sonorous low register of the solo voice enhancing the atmosphere of perpetual threat in strictly naturalistic style. Here, Bach employs the natural trumpets so effectively and flexibly that, despite their limited range of playable notes, they embody both danger and salvation, rendering every nuance of valiant self-assertion audible. In this astonishing musical portrait, it is evident that Bach, like Luther, believed fully in the physical presence but also inherent vulnerability of the devil. For that reason, it was no doubt solely for pragmatic reasons that Bach replaced the trumpet choir with strings in a later re-performance of the work.

Gentler tones imbue the following accompagnato recitative, whose soprano and tenor duet alludes not only to the “Anschläge des Satans” (the onslaught of Satan) but also refers to the protection of the angels as a higher dimension of being through its shimmering timbre and allusion to the biblical example of Daniel in the den of lions. As such, the angels form a tangible reality in the here and now as approachable messengers of heaven. This is why the tenor aria, a dance-like setting with elegant transverse flute figures, appeals to the prince of all angels to forever help his faithful followers through the reassuring employment of such a “Heldenscharen” (heroic lofty throng). That the middle section of this rather cosy setting then provides a vision of Elijah and his Chariot of Fire, likewise drawn heavenwards by angels, belongs to the surprises of this Michaelmas cantata and also proves that Bach, unlike lesser composers of his time, refrained from dulling effects through excessive repetition.

Bach did, however, experiment with mirroring effects, and in the two-verse closing chorale he not only doubled the vocal parts with strings and oboes but also added brass figures to lend the setting a grandeur that corresponds to the opening chorus. While a text indication in the sources (“Und bitten” – And ask) enables the second verse to be completed using Eber’s hymn, the reference in the first verse to “billig Lob” (which can be read today as either “cheap praise” or “willing praise”) is, contrary to the interpretation of many a modern-day concert planer on a tight budget, unlikely a form of subversive protest on the part of the Thomascantor, despite suffering the same financial plight.

Libretto

1. Chor

Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir

und sollen billig danken dir

für dein Geschöpf der Engel schon,

die um dich schweb’n um deinen Thron.

2. Rezitativ — Alt

Ihr heller Glanz und hohe Weisheit zeigt,

wie Gott sich zu uns Menschen neigt,

der solche Helden, solche Waffen

vor uns geschaffen.

Sie ruhen ihm zu Ehren nicht;

ihr ganzer Fleiß ist nur dahin gericht’,

daß sie, Herr Christe, um dich sein

und um dein armes Häufelein:

Wie nötig ist doch diese Wacht

bei Satans Grimm und Macht?

3. Arie — Bass

Der alte Drache brennt vor Neid

und dichtet stets auf neues Leid,

daß er das kleine Häuflein trennet.

Er tilgte gern, was Gottes ist,

bald braucht er List,

weil er nicht Rast noch Ruhe kennet.

4. Rezitativ — Duett: Sopran und Tenor

Wohl aber uns, daß Tag und Nacht

die Schar der Engel wacht,

des Satans Anschlag zu zerstören!

Ein Daniel, so unter Löwen sitzt,

erfährt, wie ihn die Hand des Engels schützt.

Wenn dort die Glut

in Babels Ofen keinen Schaden tut,

so lassen Gläubige ein Danklied hören.

So stellt sich in Gefahr

noch itzt der Engel Hülfe dar.

5. Arie — Tenor

Laß, o Fürst der Cherubinen,

dieser Helden hohe Schar

immerdar

deine Gläubigen bedienen,

daß sie auf Elias’ Wagen

sie zu dir gen Himmel tragen.

6. Choral

1. Darum wir billig loben dich

und danken dir, Gott, ewiglich,

wie auch der lieben Engel Schar

dich preisen heut und immerdar.

2. Und bitten dich, wollst allezeit

dieselben heißen sein bereit,

zu schützen deine kleine Herd,

so hält dein göttlichs Wort in Wert.

Walter Sparn

(1) It takes a while, dear listeners, for the fortissimo of the trumpets and the beats of the timpani to fade away and for what Bach wanted the listeners of his cantata to hear to take effect internally, for which he also used the playful delicacy of a transverse flute. Well, Bach had good reason to perform magnificently on St Michael’s Day 1724, if only because he had three trumpets, oboes and strings at his disposal and was able to compose the high jubilation of victory that we have just heard for his top trumpeter. He was able to entrust his vocalists with particularly difficult, expressive parts, such as the fierce bass aria or the dance-like tenor aria. With all this, Bach was also able to fulfil the expectations of his employer, the self-confident Leipzig Council: The day had to be prestigious, as the rich city was filled with the discerning merchants of the St Michael’s Fair.

However, the theologically well-versed St Thomas’ cantor also had spiritual reasons for such a festive cantata. Committed to the Lutheran Formula of Concord, he had to musically present the sermon pericopes prescribed for the feast of St Michael the Archangel and all the angels. These were the introit from Psalm 103, which praises the angels as “strong heroes”, and the gospel from Matthew 28, according to which the guardian angels of even the least esteemed people always see the face of God in heaven (Mt. 18, 1-10). Even more important was the epistle from the Apocalypse of John (12:7-12). It presents the heavenly battle and the triumph of Michael’s angelic hosts over the “old dragon”, the deadly accuser, in a very vivid way, but it also says that Satan, who was thrown to earth, still threatens the saints now and seeks to seduce them into apostasy. The cantata focuses on this “now” in remembrance of Michael’s victory over the tormenting spirit; it is not only the now of the Leipzig congregation, but it is also our now.

For this message, Bach and his librettist drew on a hymn of thanksgiving for the creation and the work of the angels, which in turn interprets those biblical texts. It was the so-called “Song of the Day”, which was therefore widely used in Lutheran hymnals. Of course, it was not in Reformed hymnals; after all, its melody comes from the Geneva Psalter of 1551; we sang both versions of the melody earlier. Incidentally, the current Lutheran hymnal has discarded this old-fashioned song – ironically, it is included in the collection of new (!) songs called “Atmet auf” with 10 full verses. Ah, the angels are feeling better now …

As you already know, the poet Paul Eber adapted a Latin poem of thanksgiving for the angels written by his teacher Melanchthon into German. Melanchthon has the particular distinction of unabashedly distancing himself from the traditional doctrine of angels. This angelology had speculatively imagined the angels as pure spiritual beings who, in multiple hierarchies, fill the cosmos between the heaven of God above and the earth below, hovering together and thus guaranteeing the harmonies of the spheres. Well, they didn’t flutter or drink wine, as Niklaus Peter jokingly said, but Melanchthon already rejected the cosmic round dance of angels as speculative, and one enlightened theologian even spoke of “metaphysical bats”. The problem with this is that we enlightened people can no longer associate the starry sky not only with angels, but also with God, and perhaps not even with ourselves. Melanchthon, Paul Eber and the cantata only say about the angels what is written in the biblical texts: that they are commissioned to deliver God’s word to us humans and to protect the faithful. However, this has a prehistory in heaven, their victory over Satan and his angels, as strong heroes, indeed as God’s weapons. However, their leader Michael is not even mentioned by name; only the tenor aria addresses the “prince of the cherubs”, but not the “dragon slayer” or “guardian of souls”, as which he was iconographically omnipresent. Similarly, there is no mention of an end-time battle, rather the cantata is reminiscent of this battle. Its fortissimi are not the tumult of battle, as is often said, but the fanfares of victory that resound after the decisive battle.

(2) In the recitatives and arias between the opening and closing chorales, the cantata explicates the reason for the angelic thanksgiving. It is the preservation of the faithful on earth. Even after the battle in heaven has been fought, “Satan’s fury and power” can still be a threat to their lives, which he tries to bring about without “rest and quiet” and with “cunning”, as the bass aria quotes from Eber’s song. In the anthropocentric stylisation of the angels, the librettist goes so far as to say that God created the angels for the sake of mankind, “before us”, as the alto recitative puts it, as companions of Christ and protectors of his faithful, as Melanchthon had already formulated.

Because the angels are also not allowed to rest in the face of Satan’s machinations, “all their diligence” is focussed on preserving the faithful. The cantata simultaneously intones the victory achieved and the diligence still required by the angels: with trumpet fanfares that ascend in harmonic triads and with scurrying circles of semiquavers in the strings around descending quavers. The latter sounds almost like a beehive! The librettist makes no comment on this, instead turning his attention to the Christians protected by the angel’s diligence. In the alto recitative and bass aria, he quotes the old image of the small and persecuted “poor little hive” from Eber and Melanchthon’s text. For Melanchthon and Eber, who were writing before the Religious Peace of Augsburg in 1555, this image corresponded to the real situation, namely the deadly threat to Protestants posed by their military suppression and extermination by Emperor Charles V.

In Leipzig in 1724, however, Lutheran Christians were members of an established state church. Perhaps the cantata wanted to veiledly draw attention to the fact that this church, which was still stable in terms of canon law, was by no means unchallenged, but was gradually eroding. This was due, for example, to the conversion of the sovereign, who was actually responsible for the cura religionis, to Catholicism, and even more so to the religious irritation caused by successful pietism and diffuse Enlightenment endeavours. Bach himself experienced this negatively in his collaboration with his authorised superiors, but also turned it around productively in his vocal compositional work, which integrated Lutheran-Orthodox, Pietist and early Enlightenment concerns. The anniversary of the Augsburg Confession in 1730 was soon to demonstrate how unstable the Saxon church was.

The bass aria addresses the real situation of this church with the key word of separation, even with the phonetic separation in “tre—e—e—net”. But while Melanchthon used two or even three verses on the threat, Bach simultaneously reminds us with the victory trumpets that the situation no longer needs to be objectively frightening, thus leading us to the core message of the cantata: “But well for us, that day and night / the host of angels watches to destroy Satan’s attack!” The soprano and tenor repeated this simultaneously and offset, so to speak, continuously. The indisputable biblical examples of angelic vigilance from the Book of Daniel, the den of lions and the fiery furnace, substantiate the final assertion of the recitative: “So in danger / still now the angels’ help presents itself.” Listen more closely to how the linking of two voices with the juxtaposition of diminished seventh chords and pure triads emphasises the superiority of preservation over threat in this Now!

Here we should take another look at the fierce bass aria. Its position between the alto recitative and the duet recitative makes it impossible to regard it as the centrepiece of the cantata and even to perform it separately. From the libretto, it is certainly not to be expected that it was orchestrated with timpani and trumpets like the chorale, but without the strings. But in this way it evokes the battle won in heaven in the face of the still threatening situation. This is no theatrical thunder, but rather, if I may say so, builds a dam of sound against depressive despondency and trumpets the already certain end of evil. But perhaps Bach was also able to see this, because ten years later he replaced the trumpets with strings. His later two St Michael’s cantatas and those of his sons Johann Christoph and Carl Philipp Emanuel can also be heard as a response to this ambiguity.

(3) The focus of our cantata on the guardian angels reaches its goal in the tenor aria, in my opinion quite decisively. Its text has no model in Paul Eber or Melanchthon, but is poetry by the librettist, who perhaps documents with the separately emphasised “immerdar” that he is quite familiar with Melanchthon’s stylistically very complicated “sapphic” poem. The accompaniment of the voice rising to the “high flock” – sursum corda – by the delicately moving transverse flute and the fine pizzicato of the continuo lead a prayer in the calm pace of a gavotte. This gives courage to the in itself audacious suggestion that the angels should “serve” the faithful forever and ultimately carry them to the heaven of God and the angels in the prophet Elijah’s chariot of fire. And it protects the “well but us” from self-assurance. Both the energy of victory and the need for protection are emphasised in the two verses of the final chorale, now in ¾ time. They also distinguish between thanks and petition. Ruedi Lutz has expressed this wonderfully by clearly toning down the forte of the thanksgiving in the transition to the petition and emphasising the modesty of prayer. He has rightly allowed this quiet hesitation to flow into the certainty of faith of those who “hold the divine word in high esteem” by allowing themselves to be assured of Christ’s victory over the old dragon.

Allow me to mention something else that you and I cannot hear. The cantata, whose autograph score is kept in Nuremberg, comprises 354 bars. If you divide it into 6 x 59 bars and convert the number 59 into letters (Bach often did this the other way round), you get the word “Gloria” (7+11+14+17+9+1). Make your own rhyme with this interpretation key … My personal rhyme – and please don’t think that a Lutheran has it easier than a Reformed – my rhyme boils down to gratitude for every angel that I encounter. Be it as an unexpected guest in the house or as my little granddaughter, whose cheerful play of life is allowed to contradict the toughest evil, or be it the unexpectedly good word, whose speaker doesn’t even know that it has brightened my soul. Post-metaphysical bats or esoteric kitsch – I stick to the stereoscopic view that not only children have. Artists have it too, artists of language, images and sounds. I hope you, too, will listen to the cantata again as a sounding ladder to heaven, where you can exercise your religious imagination when it comes to angels and experience something surprising. So, a sounding ladder to heaven!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).