Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz

BWV 138 // For the Fifteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Why are you troubled, my heart?) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe d’amore I+II, strings and continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

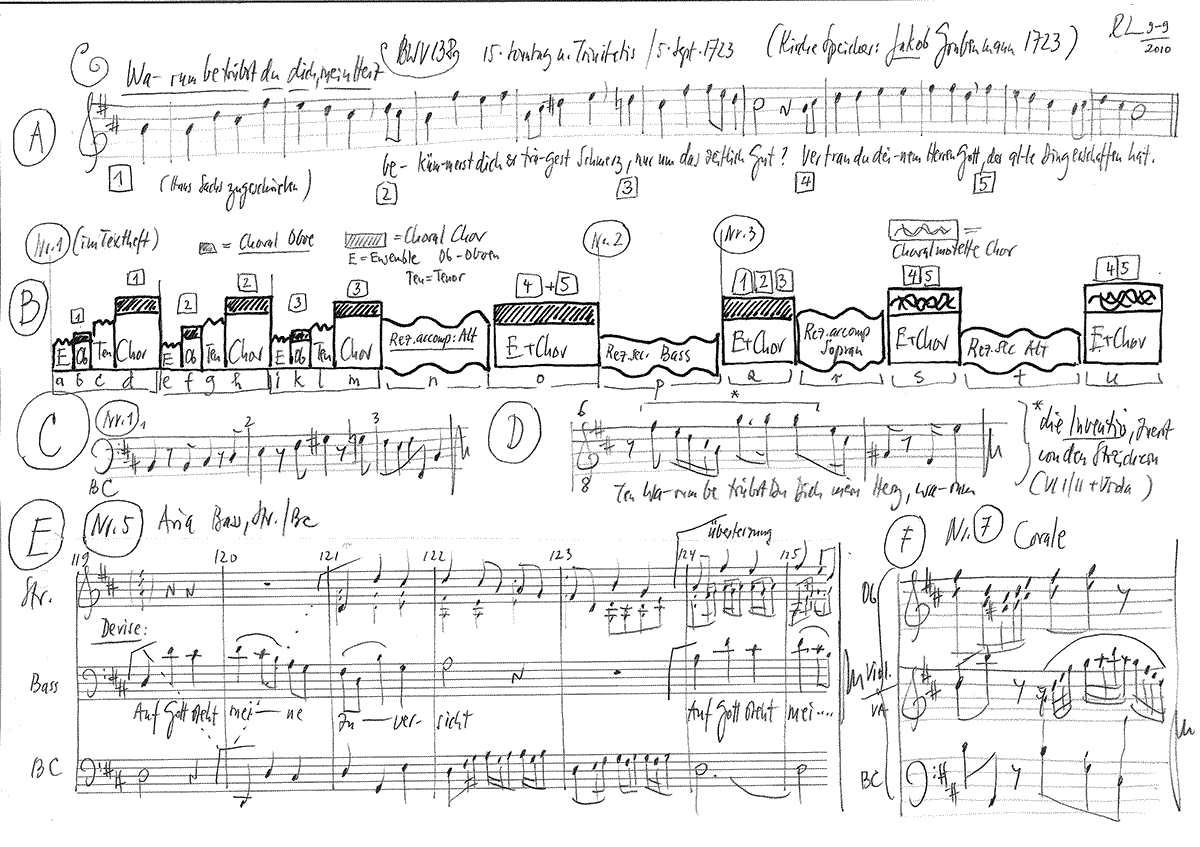

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Leonie Gloor, Noëmi Sohn, Mirjam Berli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Jan Börner, Simon Savoy, Olivia Heiniger

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Clemens Flämig

Bass

Michael Blume, Fabrice Hayoz, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Plamena Nikitassova, Monika Baer, Christine Baumann, Christoph Rudolf, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Luise Baumgartl, Thomas Meraner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Theorbo

Juan Sebastian Lima

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Christoph Wolff

Recording & editing

Recording date

09/10/2010

Recording location

Speicher AR, Switzerland

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet unknown

First performance

Fifteenth Sunday after Trinity,

5 September 1723

In-depth analysis

Although cantata BWV 138 likewise stems from Bach’s first Leipzig cantata cycle, it is significantly more modern in style than BWV 89, which at least idiomatically belongs to his Weimar period. Indeed, BWV 138, with its cantus firmus foundation, varied interaction between choral hymn singing and free soloistic commentary, and convincing orchestral interpretation of the Reformation song seems much like a preview of the chorale cantata cycle of 1724/25.

The orchestral prelude, scored for an elegiac string group and warmly singing oboes d’amore, lends the introductory chorus an equally ethereal and tragic undertone that, beyond the alternating vocal soli and tutti lines, makes effective use of the archaic hymn melody composed by an unknown Nuremberg Meistersinger. In the nigh static phrases and poignant lament of the collective ensemble, a sense of despair verging on a death wish takes shape that renders the later shift to wholesome trust in God all the more effective.

The following recitative con coro continues this gesture of self-recrimination in heartrending metaphors, which allows the hymn lines, presented in a simple cantional setting with echoing oboe figures, to appear like comfort emerging from afar. The repeat of the last two verse lines in imitative motet style (“dein Vater und dein Herre Gott” – Thy Father and the Lord thy God) contradicts the logic of the verse structure and seems a conscious decision to set the chorale with a Romantic aesthetic and interpretation “avant la lettre”.

Accordingly, the tension between lament and confidence gives way in the following tenor recitative to a spirit of self-encouragement that stuffs all worries “unters Kissen” (under the pillow), thus enabling the ensuing minuet bass aria to freely sing God’s praises. Although the couplets in this rondo setting still refer to “Sorgen”, “Armut” and “Leid” (apprehension, want and sadness), the last word is reserved for the increasingly hymnlike presentation of the motto “Auf Gott steht meine Zuversicht, mein Glaube lässt ihn walten” (With God stands all my confidence, my faith shall let him govern).

A short alto recitative then lauds this hardwon peace of mind as a foretaste of the afterlife ere the closing chorale proves Bach to be a sensitive reformer of church-music tradition. As in cantata BWV 22, which he wrote for Estomihi in 1723 as part of his job application in Leipzig, Bach eschews a simple chorale setting and instead embeds the return to the opening hymn in a spirited orchestral setting that brings the elegiac singing and sharp B-minor tonality to full musical blossom. The way the oboe phrases and shimmering running string passages inspire each other and drive the music forward is of rare beauty and transforms the archaic hymn from 1561 into a song of gripping currency and relevance.

Libretto

1. Choral und Rezitativ (Alt)

Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz?

bekümmerst dich und trägest Schmerz

nur um das zeitliche Gut?

Ach! ich bin arm,

mich drücken schwere Sorgen.

Vom Abend bis zum Morgen

währt meine liebe Not.

Daß Gott erbarm!

Wer wird mich noch erlösen

vom Leibe dieser bösen

und argen Welt?

Wie elend ists um mich bestellt!

Ach! wär ich doch nur tot!

Vertrau du deinem Herren Gott,

der alle Ding erschaffen hat.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Ich bin veracht’,

der Herr hat mich zum Leiden

am Tage seines Zorns gemacht;

der Vorrat, hauszuhalten,

ist ziemlich klein;

man schenkt mir vor den Wein der Freuden

den bittern Kelch der Tränen ein.

Wie kann ich nun mein Amt mit Ruh verwalten,

wenn Seufzer meine Speise und Tränen

das Getränke sein?

3. Choral und Rezitativ (Sopran, Alt)

Er kann und will dich lassen nicht,

Er weiß gar wohl, was dir gebricht,

Himmel und Erd ist sein!

Sopran

Ach, wie?

Gott sorget freilich vor das Vieh,

er gibt den Vögeln seine Speise,

er sättiget die jungen Raben,

nur ich, ich weiß nicht, auf was Weise

ich armes Kind

mein bißchen Brot soll haben,

wo ist jemand, der sich zu meiner Rettung findt?

Dein Vater und dein Herre Gott,

der dir beisteht in aller Not.

Alt

der dir beisteht in aller Not.

Ich bin verlassen,

es scheint,

als wollte mich auch Gott bei meiner Armut hassen,

da er’s doch immer gut mit mir gemeint.

Ach Sorgen,

ach werdet ihr denn alle Morgen

und alle Tage wieder neu?

So klag ich immerfort:

Ach! Armut! hartes Wort,

wer steht mir denn in meinem Kummer bei?

Dein Vater und dein Herre Gott,

der steht dir bei in aller Not.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Ach süßer Trost! Wenn Gott mich nicht verlassen

und nicht versäumen will,

so kann ich in der Still

und in Geduld mich fassen.

Die Welt mag immerhin mich hassen,

so werf ich meine Sorgen

mit Freuden auf den Herrn,

und hilft er heute nicht, so hilft er mir doch morgen.

Nun leg ich herzlich gern

die Sorgen unters Kissen

und mag nichts mehr als dies zu meinem Troste wissen:

5. Arie (Bass)

Auf Gott steht meine Zuversicht,

mein Glaube läßt ihn walten.

Nun kann mich keine Sorge nagen,

nun kann mich auch kein Armut plagen.

Auf Gott steht meine Zuversicht!

Auch mitten in dem größten Leide

bleibt er mein Vater, meine Freude,

er will mich wunderlich erhalten.

6. Rezitativ (Alt)

Ei nun!

so will ich auch recht sanfte ruhn.

Euch, Sorgen! sei der Scheidebrief gegeben.

Nun kann ich wie im Himmel leben.

7. Choral

Weil du mein Gott und Vater bist,

dein Kind wirst du verlassen nicht,

du väterliches Herz!

Ich bin ein armer Erdenkloß,

auf Erden weiß ich keinen Trost.