Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit

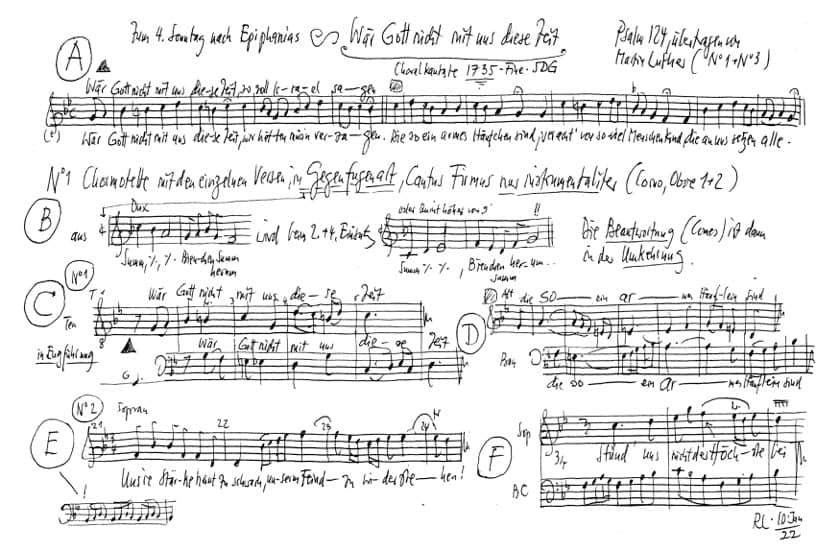

BWV 014 // For the Fourth Sunday after Epiphany

(Were God not with us all this time) for soprano, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, corno, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Alice Borciani, Cornelia Fahrion, Olivia Fündeling, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Baiba Urka

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Simon Savoy

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Zacharie Fogal, Joël Morand, Sören Richter

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Ildikó Sajgó, Judith von der Goltz

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Thomas Meraner

Corno

Stefan Katte

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Eduard Käser

Recording & editing

Recording date

18/02/2022

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

30 January 1735, Leipzig

Text

Martin Luther (movements 1 and 5), unknown source (movements 2–4)

In-depth analysis

According to a note in Bach’s own hand at the end of the original score, BWV 14 was composed for first performance on 30 January 1735. Subsequently added to the chorale cantata cycle of 1724/25, which originally featured no composition for the Fourth Sunday after Epiphany, the work numbers among Bach’s very last sacred cantatas. In keeping with both the particularly old chorale written by Martin Luther himself and Bach’s own heightened interest in early contrapuntal style during the 1730s, the introductory chorus is not composed in the concertante orchestral style typical of most of the chorale cantatas, but in the form of a polyphonic vocal motet. The development in Bach’s compositional art since the 1720s is evident in other ways, too: the vocal parts are doubled by strings and the chorale cantus firmus is assigned to two oboes and a cornett to realise a fully five-part setting. Moreover, the use of chromatic effect, syncopation and appoggiaturas lends the part writing a touch of gallant affect, introducing a compelling tension between the underlying archaic idiom and a deeply elegiac modernity.

The following soprano aria, by contrast, is firmly anchored in the sound and clear tonality of the late baroque. The fanfare-like horn part accompanied by strings joins forces with the agile soprano voice to muster a defiant energy that strives to evoke the “Stärke” (strength) described in the text – yet only to prove more clearly its inadequacy in the face of God and the enemies of his creation. That this powerful scene is punctuated by moments of introspection, particularly in the middle section, is exemplary of the vivid portrayal of affect in Bach’s mature works.

The tenor recitative radicalises the message of the aria in a merciless statement: without God, without the active protection of our mightiest brother-in-arms, humankind would be helplessly exposed to the tyranny of the enemy – as expressed in the wild rise and fall of the continuo line and dark D minor tonality – and likely “längst nicht mehr am Leben” (long no more with the living).

After such a terrifying scene, a shift to gentler tones would be in line with the typical light-and-dark contrast of most baroque cantatas and operas. And while Bach certainly fulfils this understandable wish in the following bass aria, the dramatic G minor key and strict, imitative character of the three accompanying voices (oboes I/II and continuo) in no way mitigate the earnest nature of the threat. Accordingly, the vocal cantilena resembles less a joyous refrain than an entreaty to hold strong behind the triple line of defence, whose life-saving firepower may be required at any moment. That, beyond hopes for a better life in the afterworld, there are possibly no real prospects for salvation is at least suggested in the whirling phrases of this desperately courageous music.

And so, the orchestrally accompanied closing chorale soldiers onwards and upwards over pain-filled semitones. Martin Luther’s drastic imagery is consonant with an atmosphere of existential contention, in which, then as now, a decision must be taken, regardless of the risk. The unadorned, purposeful music pervading the entire cantata never interjects itself joyously into this narrative, but rather underscores the thrust of the apodictic message of “now or never”.

Libretto

1. Chor

Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit,

so soll Israel sagen,

wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit,

wir hätten müssen verzagen,

die so ein armes Häuflein sind,

veracht’ von so viel Menschenkind,

die an uns setzen alle.

2. Arie — Sopran

Unsre Stärke heißt zu schwach,

unserm Feind zu widerstehen.

Stünd uns nicht der Höchste bei,

würd uns ihre Tyrannei

bald bis an das Leben gehen.

3. Rezitativ — Tenor

Ja, hätt es Gott nur zugegeben,

wir wären längst nicht mehr am Leben,

sie rissen uns aus Rachgier hin,

so zornig ist auf uns ihr Sinn.

Es hätt uns ihre Wut

wie eine wilde Flut

und als beschäumte Wasser überschwemmet,

und niemand hätte die Gewalt gehemmet.

4. Arie — Bass

Gott, bei deinem starken Schützen

sind wir vor den Feinden frei.

Wenn sie sich als wilde Wellen

uns aus Grimm entgegenstellen,

stehn uns deine Hände bei.

5. Choral

Gott Lob und Dank, der nicht zugab,

daß ihr Schlund uns möcht fangen.

Wie ein Vogel des Stricks kömmt ab,

ist unsre Seel entgangen.

Strick ist entzwei und wir sind frei,

des Herren Name steht uns bei,

des Gottes Himmels und Erden.

Eduard Käser

“Were God not with us all this time…”

“Were God not with us all this time” – in the text of the cantata, the subjunctive is striking: “would”, “would have”, “would be”, “would stand”. The subjunctive expresses assurance, gratitude, encouragement, but also being chosen. Moreover, one could see in it a kind of proof of God: If God did not exist, then the people of Israel – as the choir sings – “would no longer be alive”. But now they are alive, so there is God, the protector. The existence of the Israelites is “evidence” of God’s support. That sounds plausible, but the logic of this reversal is fragile – and it also tends towards dogmatism. I do not want to go into that here. Faith, after all, is not a matter of “evidence-based”.

The text spontaneously appeals to me for another reason. I love the subjunctive. The formula “What if…?” or “What if not…?” has been part of my thinking kit since I studied theoretical physics. Therefore, I would like to take a closer look at this wonderful instrument of the subjunctive in the following quarter of an hour – which may be a little unusual for you at first. And it will not be grammatical considerations.

***

Physical first. Theoretical physics always plays a game of what-if in its models, it juggles with hypotheses. Today in cosmic format. Why is the world the way it is? Physicists like to answer this question by using the subjunctive. As you know, the standard model of cosmology assumes a big bang. It represents nothing other than a primordial energy source. It is from this that the elementary particles arise and the universe expands.

And here the physicists argue formally quite similarly to the cantata text. Of course, they do not say: “If God were not with us…”, they say: “If there had not been a very specific relationship between energy density and expansion rate at the beginning of the universe, there would be no galaxies, stars, planets and physicists puzzling over this relationship”. In fact, in the history of the universe, from the Big Bang to us in this room today, there have been an enormous number of improbable fine-tunings, so that the question almost inevitably arises as to whether all these improbabilities are due to chance alone, or whether something like an inscrutable direction has controlled the whole thing. You are probably familiar with the debate on so-called Intelligent Design. This is no longer a subject for physics, but with such questions of origin, quite a few physicists – whether they like it or not – slip from physics into metaphysics.

***

Let’s stay on less slippery ground. For example, on the ground of history. Historians also ask the what-if question. For example, the Briton Niall Ferguson. He has brought so-called “virtual history” into the discussion, that is, playing out scenarios and sequences of events as they might or might not have happened. What if Jesus Christ had not been crucified? Probably there would be no martyrs, no crusades, no church music, no Bach Cantata 14, no lecture in Trogen. Many historicists turn up their noses. This is ridiculous, idle fiction, they say, and anyway their business is primarily to record what has been and what has happened. But the smart Ferguson wanted to challenge precisely this canonical self-image. Historical facts are not unshakeable, they are always interpreted, no matter how objectively they are presented. Historiography is ultimately narration.

Virtual history is therefore not directed against the objectivity of historical facts, but against an overly rigid, a “deterministic” historical view of things; against the idea that we cannot escape the entanglements of events. Things did not necessarily have to turn out the way they did. History is always factually underdetermined. We know dismayingly little about the past. And we compensate for this ignorance with what-if thinking. One should only admit this. That can loosen blockades, open horizons. What can be imagined differently can also be shaped differently. That’s why it’s good for historiography to be seasoned with a pinch of imaginative salt.

***

Our whole life consists of what-if stories, in philosopher’s jargon: of counterfactual scenarios. The ability to distinguish between the factual and the counterfactual is probably a unique feature of humans. All other animals perceive what is, we also perceive what could be. We always live in virtual worlds, even before the metaverse of Facebook. What-if thinking is the root of science, technology, literature, all creativity and culture. It can be fact-based – often a necessity – but it can also do without facts or even be directed against facts. We recently call this alternative facts. A dictionary of neologisms describes alternative facts as false information that asserts itself as a different point of view. Alternative facts are typical “for-me” facts, those that confirm my view. “The earth is flat”: false. “For me, the earth is flat”: alternative. But be careful, the phrase can backfire. Then it simply reads: “I am a flat-head.”

It is interesting in this context that we experience counterfactual scenarios as semi-real. David Hume, one of the first critical philosophical surveyors of the human mind, in his “Treatise on Human Nature” gives the example of a man in an iron cage securely fastened to a tower at a lofty height. Despite the safety, this man could not help trembling. Why not? Because he can well imagine falling down. Our imagination always exceeds the limits of the real situation. And it can make us tremble. Emotions do not distinguish between fact and fake. That’s why disinformation wars primarily target emotions. As another Briton, the poet T.S. Eliot, wrote: “Mankind cannot bear too much reality.” I don’t know, but isn’t that the perfect characterisation of our situation today?

***

Hume’s example leads me to another aspect of what-if. The cantata text explicitly says: We Israelites are in trouble, and what if God did not stand by us. So this figure of thought is based on the real threat of the enemies: “Their thirst for vengeance would tears us apart /

So wrathful are their thoughts towards us.” Now there is the inversion that plays on the ima-ginary threat: We are not currently in predicament, but what if we were threatened with one? It seems to me that we really need to get into the habit of asking this question now that the pandemic measures have been lifted. The figure of thought is ancient. It comes from the Greek school of the Stoics and is called anticipation of the bad – prae-meditatio malorum. What if the worst, the worst possible thing happened? What if new corona variants emerged?

The Stoics did not see this as fear-mongering, but on the contrary: an exercise in fear mitigation. Imagining the bad simply means switching from the sufferer’s to the observer’s perspective. I will give you an example from the Roman Seneca. One of his famous works is the Letters to Lucilius, practical advice to a younger interlocutor. The 24th letter is about a legal dispute in which Lucilius is afraid of his adversary’s retaliation. Seneca recommends a change of perspective: “… I will lead thee by another way to peace of mind. If you wish to rid yourself of all anxiety, imagine everything you fear as really imminent; measure out for yourself the size of the evil, whatever it may be, and weigh your fear: you will certainly find that either what you fear is not important or does not last.”

In other words, if you can imagine the worst, you can imagine ways out. The stoic does not want to burden himself with unnecessary worries – then he would be a neurotic – but rather to expand reality to include the imaginary. The imaginary sharpens the eye for the real. Ali S. Khan, former director of the US Public Health Protection Agency, was asked about the disastrous development of Covid-19 in the US in May 2020. “Was it a lack of scientific information or a lack of money?” the interviewer wanted to know. Khan’s response, “A lack of imagination.”

***

In short, the world is not simply what is the case. The world is everything that awaits us. In other words, more than we expect, can expect. “This time…” – the time of the pandemic – has sufficiently demonstrated to us the unpredictable complexity of events and their consequences. For a long time it was uncertain whether I would be able to present my reflection here in Trogen. Now you have heard it. And we might be inclined to interpret this event in the sense of the cantata text, as “Were God not with us…”. – I, however, lack this faithfulness. But I hear it in Bach’s music, as a kind of serenity, of humility, perhaps even of secular religiosity. An inner consolidation from the subjunctive. I think we will need it badly in the future.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).