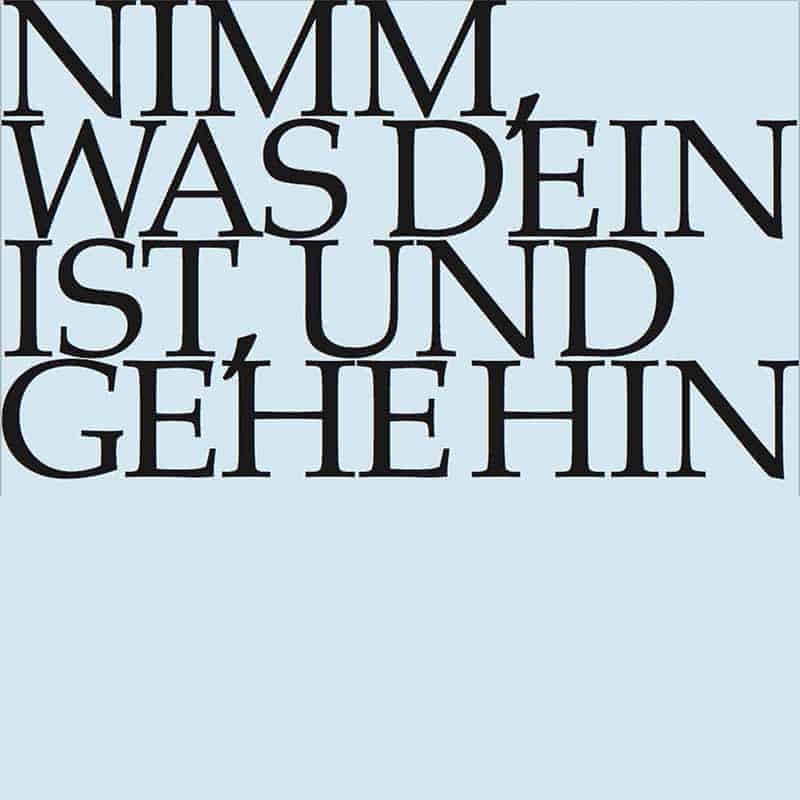

Nimm, was dein ist, und gehe hin

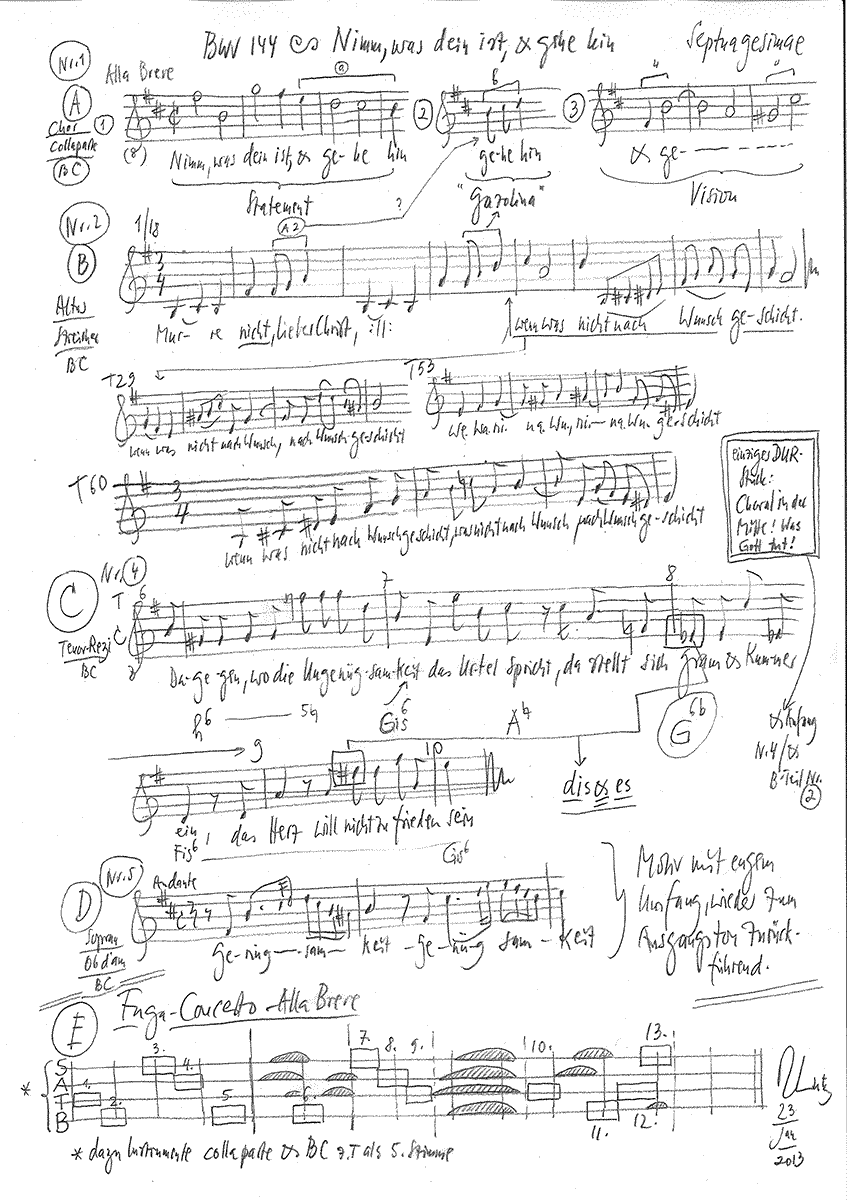

BWV 144 // For Septuagesimae

(Take what is thine and go away) for soprano, alto and tenor, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Herr, strafe mich nicht in deinem Zorn und züchtige mich nicht in deinem Grimm. Denn deine Pfeile stecken in mir, und deine Hand drückt mich. Es ist nichts Gesundes an meinem Leibe vor deinem Drohen und ist kein Fried in meinen Gebeinen vor meiner Sünde. – Verlass mich nicht, Herr! Mein Gott, sei nicht ferne von mir! Eile, mir beizustehen, Herr, meine Hilfe!

Wisset ihr nicht, dass die, so in Schranken laufen, die laufen alle, aber einer erlangt das Kleinod? Laufet nun also, dass ihr es ergreifet! Ein jeglicher aber, der da kämpft, enthält sich alles Dinges; jene also, dass sie eine vergängliche Krone empfangen, wir aber eine unvergängliche. Ich laufe aber also, nicht als aufs Ungewisse; ich fechte also, nicht als der in die Luft streicht; sondern ich betäube meinen Leib und zähme ihn, dass ich nicht den andern predige und selbst verwerflich werde. Ich will euch aber, liebe Brüder, nicht verhalten, dass unsre Väter sind alle unter der Wolke gewesen und sind alle durchs Meer gegangen und sind alle auf Mose getauft mit der Wolke und dem Meer und haben alle einerlei geistliche Speise gegessen und haben alle einerlei geistlichen Trank getrunken; sie tranken aber von dem geistlichen Fels, der mitfolgte, welcher war Christus. Aber an ihrer vielen hatte Gott kein Wohlgefallen; denn sie wurden niedergeschlagen in der Wüste.

Das Himmelreich ist gleich einem Hausvater, der am Morgen ausging, Arbeiter zu mieten in seinen Weinberg. Und da er mit den Arbeitern eins ward um einen Groschen zum Tagelohn, sandte er sie in seinen Weinberg. Und ging aus um die dritte Stunde und sah andere an dem Markte müssig stehen und sprach zu ihnen: «Gehet ihr auch hin in den Weinberg; ich will euch geben, was recht ist.» Und sie gingen hin. Abermals ging er aus um die sechste und neunte Stunde und tat gleichalso. Um die elfte Stunde aber ging er aus und fand andere müssig stehen und sprach zu ihnen: «Was stehet ihr hier den ganzen Tag müssig?» Sie sprachen zu ihm: «Es hat uns niemand gedingt.» Er sprach zu ihnen: «Gehet auch ihr hin in den Weinberg, und was recht sein wird, soll euch werden.» Da es nun Abend ward, sprach der Herr des Weinbergs zu seinem Schaffner: «Rufe die Arbeiter und gib ihnen den Lohn und heb an an den letzten bis zu den ersten.» Da kamen, die um die elfte Stunde gedingt waren, und empfing ein jeglicher seinen Groschen. Da aber die ersten kamen, meinten sie, sie würden mehr empfangen; und sie empfingen auch ein jeglicher seinen Groschen. Und da sie ihn empfingen, murrten sie wider den Hausvater und sprachen: «Diese letzten haben nur eine Stunde gearbeitet, und du hast sie uns gleich gemacht, die wir des Tages Last und Hitze getragen haben.» Er antwortete aber und sagte zu einem unter ihnen: «Mein Freund, ich tue dir nicht unrecht. Bist du nicht mit mir eins geworden um einen Groschen? Nimm, was dein ist, und gehe hin! Ich will aber diesem letzten geben gleich wie dir. Oder habe ich nicht Macht, zu tun, was ich will, mit dem Meinen? Siehst du darum scheel, dass ich so gütig bin?» Also werden die Letzten die Ersten und die Ersten die Letzten sein. Denn viele sind berufen, aber wenige sind auserwählt.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Mirjam Berli, Guro Hjemli, Jennifer Rudin, Susanne Seitter

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Fündeling, Francisca Näf, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Raphael Höhn

Bass

Valentin Parli, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Monika Altorfer, Yuko Ishikawa, Martin Korrodi, Marita Seeger

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp

Oboe d’amore

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Gerhard Walter

Recording & editing

Recording date

01/25/2013

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Quote from Matthew 20:14

Text No. 3

Samuel Rodigast (1649–1708)

Text No. 6

Albrecht von Preussen (1490–1568)

Text No. 2, 4, 5

Poet unknown

First performance

Septuagesima Sunday,

6 February 1724

In-depth analysis

Composed in 1724, BWV 144 “Nimm, was dein ist, und gehe hin” (Take what is thine and go away) is inspired by the well-known parable of the workers in the vineyard. As in BWV 14, the opening movement is set as a motet, yet Bach could have hardly interpreted the formal concept of a vocal setting strictly accompanied by instrumental voices more differently than in these two works! Whereas “Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit” (Were God not with us all this time, BWV 14) portrays the gritty affect of a threatening situation, the introductory chorus of BWV 144 draws on the Bible dictum’s descriptive impulses to act, which are portrayed here as a gesture of offering-deeds. Indeed, already in 18th century publications, commentators lauded the skill with which Bach worked with contrasting motives to convey the inherent acceleration between the statuary opening “Nimm, was dein ist” (take what is yours) and the vivid imperative “Gehe hin, gehe hin, gehe hin” (go away, go away, go away).

After the opening movement (whose laconic efficiency is reminiscent of some turba choruses from Bach’s Passions), the restrained aura and reflective rhythm of the following alto aria introduce a sense of calm, despite the muted E minor key and recurring tremololike figures in the string parts. And in fact, the setting presents an admonishment not to “murren” (murmur) but to renounce selfish desires and bear one’s share, or cross, with patience. In this aria, both the length and the somewhat resigned tone bear witness to the difficulty in persuading old Adam to give up his destructive egotism in a spirit of insightful gratitude.

In this situation, the following chorale verse “Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan” (What God doth, that is rightly done) comes across as a deliberate intervention stemming from the crisis-tested voice of experience that, with a clear shift to the bright key of G major, fosters a sense of community and goodwill for new beginnings.

The tenor recitative then sings the praises of a well-understood “Genügsamkeit” (moderation), which is celebrated by a standard, regular cadence and contrasted with the harmonically aggrieved tones of discontent arising from harbouring excessive demands. Here, the manner in which Bach and his librettist evoke the opening motive of the preceding hymn verse “Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan” as a kind of lost melodic paradise gives potent expression to a powerful allusion.

Set in a moderate andante tempo and the key of B minor (a tonality otherwise reserved for expressing ardent striving for salvation), the soprano aria lauds that form of higher contentment that could also be interpreted as the fruit of truly knowing God and nothing short of a wise rule to live by. That an oboe d’amore sings its spectral song here is fitting with the aura of a setting that affirms this inspired restraint through its modest use of compositional means.

The closing chorale “Was mein Gott will, das g‘scheh allzeit” (What my God will, let be alway) reinforces this tendency to move beyond the self in a powerful cantional setting that transforms Albrecht von Brandenburg’s early hymn of consolation into a hopeful confession of faith for Bach’s era – and indeed all time.

Libretto

1. Chor

»Nimm, was dein ist, und gehe hin.«

2. Arie (Alt)

Murre nicht,

lieber Christ,

wenn was nicht nach Wunsch geschicht;

sondern sei mit dem zufrieden,

was dir dein Gott hat beschieden,

er weiß, was dir nützlich ist.

3. Choral

Was Gott tut, das ist wohl getan,

es bleibt gerecht sein Wille;

wie er fängt meine Sachen an,

will ich ihm halten stille.

Er ist mein Gott,

der in der Not

mich wohl weiß zu erhalten:

drum lass’ ich ihn nur walten.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Wo die Genügsamkeit regiert

und überall das Ruder führt,

da ist der Mensch vergnügt

mit dem, wie es Gott fügt.

Dagegen, wo die Ungenügsamkeit das Urtel spricht,

da stellt sich Gram und Kummer ein,

das Herz will nicht zufrieden sein,

und man gedenket nicht daran:

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan.

5. Arie (Sopran)

Genügsamkeit

ist ein Schatz in diesem Leben,

welcher kann Vergnügung geben

in der größten Traurigkeit,

Genügsamkeit.

Denn es lässet sich in allen

Gottes Fügung wohl gefallen

Genügsamkeit.

6. Choral

Was mein Gott will, das gscheh allzeit,

sein Will, der ist der beste.

Zu helfen den’n er ist bereit,

die an ihn gläuben feste.

Er hilft aus Not, der fromme Gott,

und züchtiget mit Maßen.

Wer Gott vertraut, fest auf ihn baut,

den will er nicht verlassen.