Bringet dem Herrn Ehre seines Namens

BWV 148 // For the Seventeenth Sunday after Trinity

(Bring to the Lord honour for his name’s sake) for alto and tenor, vocal ensemble, trumpet, oboe I-III, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Opfere Gott Dank und bezahle dem Höchsten deine Gelübde und rufe mich an in der Not, so will ich dich erretten, so sollst du mich preisen. – Wer Dank opfert, der preiset mich; und da ist der Weg, dass ich ihm zeige das Heil Gottes.

So ermahne nun euch ich Gefangener in dem Herrn, dass ihr wandelt, wie sich’s gebührt eurer Berufung, mit der ihr berufen seid, mit aller Demut und Sanftmut, mit Geduld, und vertraget einer den andern in der Liebe und seid fleissig, zu halten die Einigkeit im Geist durch das Band des Friedens: ein Leib und ein Geist, wie ihr auch berufen seid auf einerlei Hoffnung eurer Berufung; ein Herr, ein Glaube, eine Taufe; ein Gott und Vater unser aller, der da ist über euch allen und durch euch alle und in euch allen.

Und es begab sich, dass er kam in ein Haus eines Obersten der Pharisäer an einem Sabbat, das Brot zu essen; und sie hatten acht auf ihn. Und siehe, da war ein Mensch vor ihm, der war wassersüchtig. Und Jesus antwortete und sagte zu den Schriftgelehrten und Pharisäern und sprach: «Ist’s auch recht, am Sabbat zu heilen?» Sie aber schwiegen still. Und er griff ihn an und heilte ihn und liess ihn gehen. Und er antwortete und sprach zu ihnen: «Welcher ist unter euch, dem sein Ochse oder Esel in den Brunnen fällt und der nicht alsbald ihn herauszieht am Sabbattage?» Und sie konnten ihm darauf nicht wieder Antwort geben. Er sagte aber ein Gleichnis zu den Gästen, da er merkte, wie sie erwählten, obenan zu sitzen, und sprach zu ihnen: «Wenn du von jemand geladen wirst zur Hochzeit, so setze dich nicht obenan, dass nicht etwa ein Vornehmerer denn du von ihm geladen sei, und dann komme, der dich und ihn geladen hat, und spreche zu dir: ‹Weiche diesem!› Und du müsstest dann mit Scham untenan sitzen. Sondern wenn du geladen wirst, so gehe hin und setze dich untenan, auf dass, wenn da kommt, der dich geladen hat, er spreche zu dir: ‹Freund, rücke hinauf!› Dann wirst du Ehre haben vor denen, die mit dir zu Tische sitzen. Denn wer sich selbst erhöht, der soll erniedrigt werden; und wer sich selbst erniedrigt, der soll erhöht werden.»

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Cornelia Fahrion, Ulla Westvik, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger

Alto

Anne Bierwirth, Antonia Frey, Laura Kull, Simon Savoy, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Tobias Mäthger, Klemens Mölkner, Tiago Oliveira

Bass

Grégoire May, Christian Kotsis, Simón Millán, Tobias Wicky, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler Gomez, Olivia Schenkel, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Clara Espinosa Encinas, Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Jaroslav Rouček

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Thomas Metzinger

Recording & editing

Recording date

25/10/2024

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

19 September 1723 or 23 September 1725, Leipzig

Text

Movement 1: Psalm 29:2; movements 2–5: unknown poet (based on Picander, 1725); movement 6: no extant text, supplemented with text by Lübeck (before 1603)

In-depth analysis

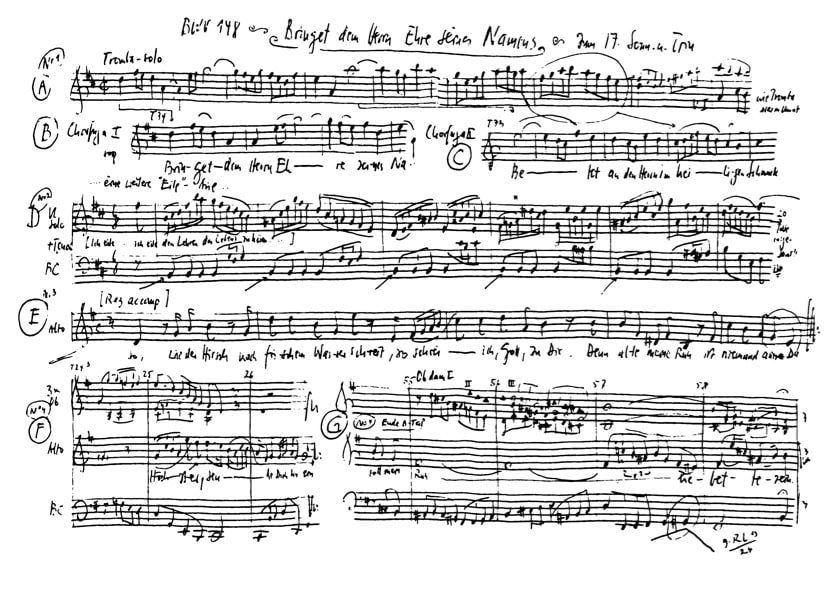

The surviving sources for BWV 148 were passed down posthumously by Bach’s students, and key questions regarding the librettist and date of composition remain unanswered. The musical material, however, strongly indicates that the work originated during Bach’s mature Leipzig period in the mid-1720s. The opening chorus, set to a verse from Psalm 29, offers a compact setting of a biblical dictum, featuring a brilliant trumpet solo in splendid concertante dialogue with the accompanying strings. The vocal parts initially take up these motifs in block-like declamations, from which delicate imitative passages repeatedly emerge, without diminishing the movement’s compelling energy.

This virtuosic flair remains prominent in the following tenor aria. Drawing on the key words “Ich eile” (I hasten), the setting unfolds as a veritable perpetuum mobile for violin, tenor and continuo. Nonetheless, the underlying virtue of faithful “hören” (listening) imbues the movement with a humbly subdued character, thus explaining Bach’s choice of a muted, B minor key. The middle section then blossoms into a rapturous vision of fulfilled musical proclamation: “Wie rufen so schöne das frohe Getöne zum Lobe des Höchsten die Seligen aus” (How lovely a summons of sounds of glad music to praise of the Highest his saints there to make).

This urgent longing for God’s word and spiritual nourishment finds poignant expression in the alto recitative. Commencing with the famous opening of Psalm 42 (“So, wie der Hirsch nach frischem Wasser schreit” – Like as the hart for cooling waters cries) and employing a deeply expressive G-major string accompagnato, the movement unfolds as a study of a life shaped by faith and bearing witness, one that extends to inner union with God: “denn Gott wohnt selbst in mir” (For God doth dwell in me). In the alto aria, too, this interior experience of uplifting love evolves into a musical happening. In a setting accompanied by two emblematic oboes d’amore as well as a taille and continuo, the vocalist imitates the woodwinds’ breathy timbre, conveying a gesture of complete openness to the healing message and presence of the Highest. The entire movement is imbued with an infectious lightness that appears unencumbered by all earthly gravity through “Glaube, Liebe, Dulden und Hoffen” (faith and love and trust and patience).

The ensuing tenor recitative unfolds in dramatic twists and turns, imploring God’s spirit to be a comforting companion in life – one who will guide the believer in godly conduct until the practice of regular Sunday worship gives way to the eternal “grossen Sabbat” (mighty Sabbath) in heaven. The closing chorale, marked by a subdued earnestness, survives only as a cantional setting with a cantus firmus. Though the original text remains unknown, the music is most familiar today as the hymn “Auf meinen lieben Gott” (In my beloved God). Our recording follows the recommendation of the New Bach Edition in using that hymn’s sixth verse “Amen zu aller Stund” (Amen at every hour) – an apt choice, as the final phrase praising God’s name echoes the import of the opening chorus, bringing the cantata to a theologically coherent close.

Libretto

1. Chor

Bringet dem Herrn Ehre seines Namens,

betet an den Herrn im heiligen Schmuck!

2. Arie — Tenor

Ich eile, die Lehren des Lebens zu hören,

und suche mit Freuden das heilige Haus.

Wie rufen so schöne

das frohe Getöne

zum Lobe des Höchsten die Seligen aus!

3. Rezitativ — Alt

So, wie der Hirsch nach frischem Wasser schreit,

so schrei ich, Gott, zu dir.

Denn alle meine Ruh

ist niemand außer du.

Wie heilig und wie teuer

ist, Höchster, deine Sabbatsfeier!

Da preis ich deine Macht

in der Gemeine der Gerechten.

O! wenn die Kinder dieser Nacht

die Lieblichkeit bedächten!

Denn Gott wohnt selbst in mir.

4. Arie — Alt

Mund und Herze steht dir offen,

Höchster, senke dich hinein!

Ich in dich, und du in mich;

Glaube, Liebe, Dulden, Hoffen

soll mein Ruhebette sein.

5. Rezitativ — Tenor

Bleib auch, mein Gott, in mir

und gib mir deinen Geist,

der mich nach deinem Wort regiere,

daß ich so einen Wandel führe,

der dir gefällig heißt,

damit ich nach der Zeit

in deiner Herrlichkeit,

mein lieber Gott, mit dir

den großen Sabbat möge halten!

6. Choral

Amen zu aller Stund

sprech ich aus Herzensgrund;

du wollest uns tun leiten,

Herr Christ, zu allen Zeiten,

auf daß wir deinen Namen

ewiglich preisen. Amen.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Thomas Metzinger

What is spirituality?

Why is sacred music so beautiful? Why does it sometimes touch us so differently, in a much deeper way than other forms and types of music? What exactly is this special kind of inwardness – and what is it anyway: “spirituality”?

1

Spirituality – as I said in my essay “Spirituality and intellectual honesty”[1] – is basically the exact opposite of religion. The opposite of religion is not science, but spirituality. Many people have long been searching for a radically honest, intellectually honest form of spirituality. But what could that actually mean? Intellectual honesty means that you are simply not prepared to lie to yourself. It also has something to do with very old-fashioned values such as decency, sincerity and honesty towards oneself, with a certain form of “inner decency”. You could perhaps say that intellectual honesty is a very conservative way of being truly subversive.

As we all know, a rebellion against organised religion has taken place over the last fifty years, at least initially very successfully. Far away from the churches, something new has emerged, a global spiritual counterculture – and at least in parts it is still a genuine “spiritual counterculture” today. Countless people have taken matters into their own hands, and this development can be considered one of the most important cultural innovations of the 20th century in Western countries.

In the current, living manifestations of spirituality, however, it is primarily about practice and not so much about theory. It is about a certain form of inner action and not about piety or dogmatic adherence to certain beliefs. Spirituality is essentially an epistemic attitude. Spiritual people do not want to believe, they want to know. It is about an experience-based form of cognition that has to do with a very precise but gentle form of inner awareness, with bodily experience and the systematic cultivation of certain altered states of consciousness. Typically, the form of knowledge sought is described as a very specific form of self-knowledge that is not only liberating but also reflexively focussed on the spiritual practitioner’s own consciousness. One could say that it is about awareness as such, dissolving the subject-object structure and going beyond the individual first-person perspective.

In his sermon Iusti vivent in aeternum, Meister Eckhart (1260-1328) said:

“Some simple-minded people believe that they should see God as if he were standing there and they here. That is not the case. God and I are one.”

At the end of the first recitative of our cantata, it says: “For God himself dwells in me.” Spiritual realisation therefore often occurs in connection with the systematic cultivation of certain altered states of consciousness, so-called “non-dual” states.

2

A few years ago, I founded a scientific research project in which we are investigating the experience of “pure consciousness” in meditation in great detail. Mankind knows many different words for this experience: one example is Meister Eckhart’s “soul ground”, the “groundless ground of the Godhead”, of which he says:

“All our perfection and all our bliss depend on crossing and transcending all that is creaturely, all that exists, and coming to the ground that is groundless.”

Sermon Adolescens, tibi dico: surge

Beguine of Hadewijch (also known as Hadewijch of Antwerp or Hadewijch of Brabant) was a member of European women’s mysticism, a philosopher, poet and mystic of the 13th century – and she was already saying the same thing before Eckhart. She already used the two terms “reason” (gront in Middle Dutch) and “groundlessness” (grondeloesheit). And interestingly enough, it is precisely this “groundless ground” that is also a classic motif of Buddhist philosophy.

Asian terms for pure consciousness are, for example, the dharmakāya (the “truth body” of the Buddhist Pāli canon); rig pa (in Tibetan Dzogchen the “pure awareness”, the “realisation of the ground”, the spontaneous presence of the original “primordial awareness”); samādhi (the “level intellect”, as we find it in the Bhagavad Gita or in the Yoga Sūtra of Patañjali); sat-chit-ananda (“pure being, consciousness and bliss” in Hindu philosophy); turīya (since the oldest Upanishads, the idea of a fourth state of “pure consciousness” that underlies the three ordinary states – waking, dreaming and dreamless deep sleep); or ye shes (the “timeless awareness of primal wakefulness”, for example in Vajrayāna Buddhism).

As part of our research project, together with my Swiss colleague Alex Gamma, I interviewed more than 3,500 meditators from 57 countries in detail about their experience of pure consciousness. I won’t bother you with scientific details now, if you want to know more about this, you can find it in my book “The Elephant and the Blind”.[2] What is interesting, however, is how many meditators, when asked by us to describe a single, paradigmatic experience of pure awareness, testified to a deep sense of profundity and existential relevance. At the same time, however, it became apparent how few of them chose to interpret their experience in explicitly religious terminology. And yet they do exist. Here are three examples:

267 […] It was a very profound experience for me. It was as if I had got an impression of what “God” really is for the first time.

540 […] At the same time, the flow of my thoughts decreases more and more, and my consciousness becomes very quiet and peaceful. But this is only a transitional stage. Because after a while there is a feeling of increasing expansion, not only of consciousness but also of the body. The feeling that accompanies this is love. As a Christian, I perceive it as God’s love touching me and at the same time igniting my love for him and all creatures within me.

3579 Again and again in meditation I experience that I feel as one with God and God in everything. This is the God of all religions, not that of Christianity, detached from space and time. It is difficult to put into words because it is first and foremost an experience of oneness. There is no more ‘I’ or ‘not I’. I feel one with the primordial source, completely within and completely without. All separation is cancelled. There is only total presence. All conflicts, everything is void and no longer exists.

3

We have psychometrically analysed the description given by meditators around the world, which has led to a 12-factor statistical solution.[3] Again, no scientific details, but I think factor 8 is most relevant to our question. We have called it “emptiness and non-egoic self-awareness”. I think that this factor probably most clearly expresses the spiritual essence (i.e.: the “spirituality”) of the experience in question. Let’s stay concrete again, here are three experience reports for you:

1350 […] When the corresponding state arises, it is like the seeing of seeing or the awareness of being aware.

1545 […] A non-physical space arose in me, which enlarged from moment to moment and in which the boundaries between the perceiver and the perceived object became blurred. At the same time, this space was aware of itself. […]

156 This was predominantly an experience of emptiness, not as an object, but as self-recognising emptiness/consciousness. There was much clarity (self-recognising awareness) and a joy that lasted for several days. […]

I think this quality of non-egoic self-awareness perhaps comes closest to what many describe as an irreducibly spiritual state of consciousness: it is perhaps what characterises the deepest meaning of the word “spirituality”. A form of conscious experience and cognition that is completely independent of religious belief systems. It is the phenomenological anchor for what many meditators describe afterwards as the spiritual essence of their experience or even as their “true self”.

2120 […] I became aware of the fact that “thinking” does not have primacy in my experience, but that awareness has primacy. Thinking takes place in this awareness, which is also aware of itself.

Perhaps most importantly, the experience feels like the non-dual version of self-knowledge, like a particularly intimate form of being-in-contact-with-self: yes, consciousness is aware of itself, but in the experience itself there is neither subject nor object.

[…] It was a clear awareness, but without thought; non-dual (no subject-object, but also not so much of a wholeness). I wasn’t quite sure about “time” or “space” or “thought” or “body” (or didn’t feel it). But I knew that something/someone (I assume: myself) existed then and now. It certainly wasn’t “enlightenment”, just awareness manifesting itself while no thoughts were present. It is the background awareness behind all thoughts and perceptions, and it knows itself.

No one has seen this aspect of spiritual experience as clearly as the Tibetan Buddhists. To conclude on a very concrete note, here are three classic quotes with practical instructions:

Rgyal ba Yang dgon pa (1213-1258), who died shortly before Meister Eckhart was born:

“This naked clarity and emptiness beyond the intellect. If you let it be itself naturally, then it will recognise itself. […] Her self-realisation is the core of the practice. When she meets herself face to face, she dissolves into herself.”

Song of the Seven Introductions II (2, 4)

For the Tibetans, it is not about making something, but only about recognising something. Here, half a century later, Longchen Rabjam (1308-1363):

“It’s about staying in the continuum of recognition without fabricating anything.”

The Precious Treasury of the Basic Space of Phenomena (11)

And at the time of Martin Luther, Dakpo Tashi Namgyal (ca. 1513-1587) said:

“When stillness is there, recognise exactly that within the stillness and maintain it with reflective mindfulness.”

Moonbeams of Mahāmudrā II (10)

So what has our research shown? The quality of experience in question is not ego-like, it has nothing evaluative, selective or active about it. In other words, it is effortless, does not represent a reaction to anything and is not purposeful. Accordingly, it does not contain a consciously experienced feeling of control. Nobody possesses it. There is no feeling of being mine. It is holistic, it lacks internal structure. In this case, the phenomenal signature of self-knowledge also has no autobiographical component. It appears as timeless and spontaneously present: there is therefore no “inner narrative”, it has nothing to do with personality traits or self-conscious mental behaviour, including self-referential thoughts or emotions. If we really take the phenomenology in question seriously, then there is a strong sense in which self-recognising pure consciousness has nothing to do with you.

This specific form of inner experience was already well known to those scholar-practitioners who came many centuries before us and was precisely described by them, for example in the form of the Tibetan rang rig ye shes, which is translated as “self-recognising timeless awareness” or “self-recognising alertness”. The bridge to the Western tradition is clearly recognisable: after all, the philosophical point of Meister Eckhart’s concept of the “ground of the soul” is precisely that the non-dual knowledge of God is a form of self-knowledge.

At the beginning I asked: Why is sacred music so beautiful? What exactly is this special kind of inwardness? My provisional answer is: truly sacred music does not transport us into a metaphysical dream world, but rather enables a very specific form of self-knowledge and spiritual clarity.

So what is “spirituality”? Spiritual persons are people who have an openness to the form of realisation inherent in these states of consciousness and who therefore cultivate them in their own spiritual practice. If spirituality is seen as a characteristic of states of consciousness, then it is non-egoic self-awareness: it is the simple and pure awareness of awareness itself, it is the quiet clarity that has awakened to itself. And spiritual music is precisely the music that leads us to such states of consciousness.

If it is true that the quality of self-recognising awareness, completely liberated from a sense of self, is always already within us, but that we cannot “make” it and actually only have to recognise it, and if it is really true that this clear stillness, constantly awakening to itself, is the very essence of what spirituality actually, in reality, is – then we should also be able to discover precisely this stillness behind the music, in the states of consciousness that Johann Sebastian Bach’s work opens up for us.

[1] T. Metzinger (2014), Der Ego-Tunnel, Munich: Piper, pp. 373-413. See also https://thomasmetzinger.com/.

[2] T. Metzinger (2023), Der Elefant und die Blinden, Berlin, Munich: Berlin Verlag.

[3] A. Gamma & T. Metzinger (2021), The Minimal Phenomenal Experience questionnaire (MPE-92M): Towards a phenomenological profile of “pure awareness” experiences in meditators. PLOS ONE 16 (7): e0253694.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253694. See also https://mpe-project.info.