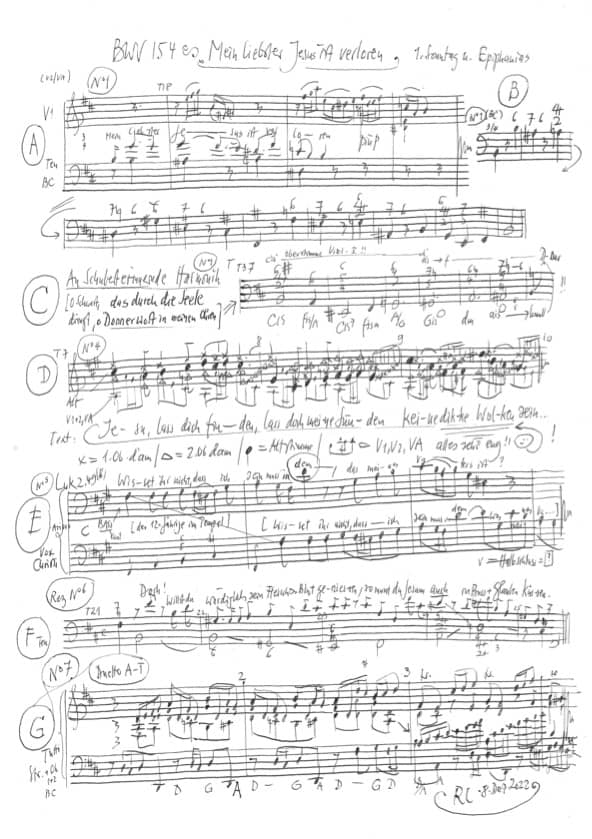

Mein liebster Jesus ist verloren

BWV 154 // For the First Sunday after Epiphany

(My precious Jesus now hath vanished) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe d’amore I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen, Dorothee Mühleisen, Petra Melicharek

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sonoko Asabuki, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe d’amore

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter, Anselm Hartinger

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Alfred Pfabigan

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/02/2023

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

9 January 1724, Leipzig

Text

Unknown source (movements 1, 2, 4, 6, 7); Martin Jahn (movement 3); Gospel of Luke 2:49 (movement 5); Christian Keymann (movement 8)

In-depth analysis

Personal experience has taught many of us how fleeting the joy of Christmas can be, and the brief nature of the season is reflected in the events of the liturgical year, too. Indeed, although the period of Epiphany is still bathed in the light of the nativity, it foreshadows the newborn Christ’s ultimate path to the cross and his departure from this world. A portent of this is seen in the story of Jesus being found in the temple after leaving his parents without permission, a narrative that in Baroque times was interpreted more broadly as a symbol of the separation of the faithful soul and the church from their Saviour.

It is this interpretation, then, that comes to bear in the cantata “Mein liebster Jesus ist verloren” (My precious Jesus now hath vanished), which was first performed on 9 January 1724. In keeping with the reference to personal loss, the opening movement is not assigned to the choir, but to a solo tenor. In this pain-filled B-minor setting, the strings swell to an impassioned lament, only for their dotted, overture-like gesture to repeatedly subside into an unanswered piano. The reference in the ensuing lines to Johann Rist’s hymn “O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort” (Eternity, thou thundrous word) is echoed in the tremolo orchestral accompaniment, a figure that not coincidentally recalls Bach’s setting of the same hymn in the cantata BWV 60 composed only a few weeks earlier.

The tenor recitative, too, alludes to the search for Jesus set out in Luke, but recasts it as the “brünstiges Verlangen” (fervent desiring) of the faithful soul for the Saviour, the loss of whom is described as the greatest possible misfortune. The four-part chorale setting of “Jesu, mein Hort und Erretter” (Jesus, my shield and redeemer) then, as it were, offers the congregation the opportunity to join in the search; here, we can still detect the “liebstes Jesulein” (dearest Jesus child) of the Christmas story behind the “starker Schlangentreter” (mighty serpent-slayer). Accordingly, Bach portrays this devout quest in a pastoral 12/8-time aria in which the solo alto lines nestle closely to the two trusting, murmuring oboes. In this setting, the obstacle posed by the “dicke Sündenwolken” (swelling clouds) seems to have already been charmed away by the aria music with its high bassett accompaniment.

By contrast, Jesus’ well-known answer, “Wisset ihr nicht, dass ich sein muss in dem, was meines Vaters ist” (Know ye then not that I must be there where my Father’s business is), is conceived as the weighty appearance of a protagonist who is not quick to let himself be “found” and instrumentalised. The arioso setting is thus assigned to the pointedly unchildlike bass voice, which is coupled with a melodically equal continuo in an industrious duet that evokes less the bliss of the manger scene than the Saviour’s assiduous “treading of the winepress.” The tenor recitative then describes the biblical scene of reunion in the love language of the Song of Solomon. Upon the invitation to follow Jesus into his temple, however, the personal sense of pious awakening gives way again to a broad confessional commitment to the community of church and sacrament.

With all affliction thus overcome, the festive alto and tenor duet is free to celebrate this new-found unity. In view of the imitative beginning of the final section “Ich will dich mein Jesu nun nimmermehr lassen” (I will, O my Jesus, now nevermore leave thee), it cannot be ruled out that this dance-like setting accompanied by strings and woodwinds originates from an older cantata, perhaps even from a secular, congratulatory work.

No chorale can express this confidence of spirit better than Christian Keimann’s powerful confessional hymn from 1658. Evidently, the notion of a personal bond with Jesus embodied by the cantata was so salient that Bach and his unknown librettist took the liberty of modifying the sixth verse of the hymn such that it begins with the opening phrase “Meinen Jesum lass ich nicht” (This my Jesus I’ll not leave).

Libretto

1. Arie — Tenor

Mein liebster Jesus ist verloren:

O Wort, das mir Verzweiflung bringt,

o Schwert, das durch die Seele dringt,

o Donnerwort in meinen Ohren.

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Wo treff ich meinen Jesum an,

wer zeiget mir die Bahn,

wo meiner Seelen brünstiges Verlangen,

mein Heiland, hingegangen?

Kein Unglück kann mich so empfindlich rühren,

als wenn ich Jesum soll verlieren.

3. Choral

Jesu, mein Hort und Erretter,

Jesu, meine Zuversicht,

Jesu, starker Schlangentreter,

Jesu, meines Lebens Licht!

Wie verlanget meinem Herzen,

Jesulein, nach dir mit Schmerzen!

Komm, ach komm, ich warte dein,

komm, o liebstes Jesulein!

4. Arie — Alt

Jesu, laß dich finden,

laß doch meine Sünden

keine dicke Wolken sein,

wo du dich zum Schrecken

willst für mich verstecken,

stelle dich bald wieder ein!

5. Arioso — Bass

«Wisset ihr nicht, daß ich sein muß in dem, das meines

Vaters ist?»

6. Rezitativ — Tenor

Dies ist die Stimme meines Freundes,

Gott Lob und Dank!

Mein Jesu, mein getreuer Hort,

läßt durch sein Wort

sich wieder tröstlich hören;

ich war vor Schmerzen krank,

der Jammer wollte mir das Mark

in Beinen fast verzehren;

nun aber wird mein Glaube wieder stark,

nun bin ich höchst erfreut;

denn ich erblicke meiner Seelen Wonne,

den Heiland, meine Sonne,

der nach betrübter Trauernacht

durch seinen Glanz mein Herze fröhlich macht.

Auf, Seele, mache dich bereit!

Du mußt zu ihm

in seines Vaters Haus, hin in den Tempel ziehn;

da läßt er sich in seinem Wort erblicken,

da will er dich im Sakrament erquicken;

doch, willst du würdiglich sein Fleisch und Blut genießen,

so mußt du Jesum auch in Buß und Glauben küssen.

7. Arie — Duett: Alt und Tenor

Wohl mir, Jesus ist gefunden,

nun bin ich nicht mehr betrübt.

Der, den meine Seele liebt,

zeigt sich mir zur frohen Stunden.

Ich will dich, mein Jesu, nun nimmermehr lassen,

ich will dich im Glauben beständig umfassen.

8. Choral

Meinen Jesum laß ich nicht,

geh ihm ewig an der Seiten;

Christus läßt mich für und für

zu den Lebensbächlein leiten.

Selig, wer mit mir so spricht:

Meinen Jesum laß ich nicht.

Alfred Pfabigan

“You’ll laugh, the Bible!” with these oft-quoted words, the thirty-year-old Bert Brecht is said to have answered the question of a reporter from the Ullstein magazine “Die Dame” about the most important book in world literature in 1928, i.e. after the great success of the “Threepenny Opera”.

This is often interpreted as a provocation by the then already communist-minded aspiring literary figure, but beware: Brecht had enjoyed a religious upbringing, the fifteen-year-old’s first dramatic fragment – it was premiered in 2013 in Augsburg’s Barfüsserkirche, where Brecht was baptised and confirmed – is entitled “The Bible”, and allusions to constellations and episodes from the Holy Scriptures run through the work.

But does such a judgement not require a certain reading attitude? Above all, how did Brecht deal with the promise of salvation proclaimed in the Gospels? The episodes from Jesus’ life reported in the Gospels allow for several perspectives. Many deal with deeply human events and constellations – birth, death, sin, longing, punishment and forgiveness – and at the same time, in accordance with the dual nature of the protagonist, refer to the eschatological dimension. When read in the flowing text, it is obvious; if we pick out one of the pieces, many of them invite us to a seeming universalisation. This is probably an essential seductive strategy of the text: that the everyday, in all its occasional drama, but also its case-by-case banality, points to the higher.

Brecht could not escape this, even if he individualises the collective redemption through the buccaneer Jenny and introduces a “ship with twenty sails” as the redeemer.

Such a quasi-secularised reading is also promoted by Max Weber’s classic diagnosis of the “disenchantment” of the world, of a sober, pragmatic, rule-oriented way of thinking as a characteristic of modernity. Apparently, the disappearance of what Weber calls “magic” also means an impoverishment, sometimes even a mortification of those who still attribute a higher significance to “magic” – if we take off the cultural-critical glasses, then the “disenchantment” often causes a trivialisation. But as a heuristic procedure, it expands the spectrum of meaning of the text.

This also applies to Luke 2:41-50, from whose context, using spiritual poetry, the textual material of the cantata BWV 154 originates. “My dearest Jesus is lost”, “where do I find him?”, “let yourself be found” are the central textual statements. Luke reports a story deeply rooted in everyday human life, an incident of the kind reported to us with some regularity in the tabloid press. It happened to a single family, but at the same time it heralds the disruption of everyday life that will change not only the life of this family, but that of an entire society.

Apparently, the protagonists are simple people, a carpenter, his wife and a son. But Luke has informed us beforehand that the father Joseph is from the lineage of David, and will later confirm this with a precise list of ancestors. There has been talk early on, strange events have taken place around pregnancy and childbirth, and the child is connected to the slaughter ordered by Herod.

Following the religious regulations, this family made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem for Passover and presented their son, who had matured from a child to a youth, in the temple. The return home was probably hurried or poorly organised – perhaps the parents also trusted in the adolescent’s maturity, whatever the case may be: after one day it turns out: Jesus is not in the travelling party! Three themes are alluded to from now on: Despair – separation – the imposition that the double character of the youth initially means for his mother. All three will lead us from the sphere of everyday life into that of the child’s divine character – so it is the separation that I will make from now on, against the intention of the text as a whole and isolated as an episode.

The parents hurry back to Jerusalem, wondering through the presumed whereabouts of the son for three days that must seem endless to them. The fantasies that torment them in their seemingly endless search are understandable, Luke remains – as usually – terse; but the theme of the lost child is and will always be artistically portrayed: Did the child suffer an accident, did she get lost in search of her parents, did she even fall victim to a crime, like the little girl in Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s “Promises” – or was she simply disobedient and will now experience adventures similar to those of little Kevin in the film “Home Alone 2: Lost in New York”?

Finally – probably already totally dissolved – the parents go back to the starting point, to the temple, and find Jesus among the teachers who were supposed to question him, as listeners and disputants. And the boy, whose “insight and answers” amazed everyone, succeeded in doing so for several days.

This sounds like a happy ending, almost like the original version of Andersen’s child who perceives more than those in power, but it gives the incident a new everyday quality. The word “Jesus boy”, used in many translations, misses the reality of an adolescent in that time and geographical space – Jesus is on the threshold of coming of age. This also brings us to an archetypal situation: the adolescent has gone his own way, as is typical of his age. And in doing so, he has caused his mother pain and fear.

And at the same time, another aspect familiar to us is alluded to here: the parents’ grandiose astonishment at the peculiarity of an exceptional child and the resulting notorious difficulties in understanding. The rule-breaking characteristic of puberty reinforces this constellation.

But this child, this youngster, goes beyond the scope of a mere human exceptionality – he is not one of those “highly gifted” who, misunderstood by parents and teachers to whom they are superior, are often discriminated against as being less gifted. The incomprehension and despair of parents who realise that their child is someone else and lives beyond the limits of understanding despite all willingness to tolerantly “understand”. He is the Son of God, and that gives the three aspects the bridge into metaphysics. Mary and Joseph are more than desperate parents, they stand for the image of a humanity in search of God. Jesus is more than an adolescent in search of autonomy – he, who until now has only been someone to be discussed, will define himself here for the first time. And in doing so, he will touch on another theme – in an all-too-familiar reading: that of the child who doubts the legitimacy of his father and thinks more highly of the true father. This adolescent thus lives in two spheres, but at first he does not rebel, but “was subject to them”.

But before that, in response to Mary’s accusation that Joseph – who is called his father here – and she had sought him with pain, he affirms his otherness: “Why did you seek me? Did you not know that I must be in that which is my Father’s?” Jesus is outing himself here. The fact that the parents “did not understand the word” hints at a central theme of his life: the struggle for recognition as the Son of God and the associated special character of his earthly mission. At the speech fight in the temple, for example, the Pharisees will ask the carpenter’s son about his “authority”. And the inhabitants of Gadara will ask him – notwithstanding the healing of a possessed fellow citizen – to leave their town. The phenomenon of God becoming man is indeed unthinkable and unacceptable according to an everyday logic.

As far as the attitude of the Mother of God is concerned, is there a contradiction between Luke and John 2:4 or can we see a development here? In the account of the wedding at Cana it is ever suggested that Mary had an ulterior motive in telling Jesus that the wine was running out, and that Jesus initially rebuffs – “Woman, what about me and you? My hour has not yet come?” – but then is obedient, so to speak, and turns water into wine. That’s when the mother-son dynamic changed: Jesus performs his first miracle at the command of and in agreement with his mother.

The struggle for “authority” begins in this confrontation of the 13-year-old with the teachers, and it is no wonder that the question of the content of these conversations already occupied the apocrypha and pseudo-epigraphs – for example, the Gospel of the Childhood of Thomas, written in the second century, which not only attributes miracles to the child Jesus, which we also find in the legends surrounding Buddha, but also has him act wickedly.

The content of these conversations also occupies pious poetry. Particularly worthy of mention is the Graz musician and disciple of Paganini Jacob Lorber (1800-1864), the self-proclaimed “writing servant of God”, to whom the command “Take the stylus and write” was revealed in 1840 and who – according to his statement – filled about 25 books with 10,000 printed pages more or less in one go without supporting literature on the dictation of God. As a supplement to his “Youth of Jesus”, a new revelation of the apocryphal Protoevangelium of Jacobus, he wrote in 1859/60 the 150 printed pages of “The Three Days in the Temple”. Here Jesus argues with the teachers – asking about the earthly presence of the Virgin and her Son prophesied by Isaiah, and insisting that Mary and he are them. “What would you do if I were the Messiah?” he says here.

An international Jacob Lorber community still distributes the books today; they dispute the monopoly of the evangelists and believe in permanent revelation. The enigma that Luke gives us by his concealment of the content of the conversation is obviously difficult to bear.

The content of the conversations in the temple also preoccupied the Portuguese Nobel Prize winner José Saramago, who published a “Gospel of Jesus” in 1991, in which the Lord narrates in first person. The Vatican criticised the writing as blasphemous. In this subversive text, Jesus suffers from his dual existence, his mission and feels guilty about his earthly way of life. In the temple, he still speaks of his father being dead and focuses on a single question: the hereditability of guilt and thus the justification of the idea of original sin because of the offence of Adam and Eve.

Brecht and Saramago have led us to the political left, from which I would like to cite a somewhat absurd example at the end. In the context of the personality cult around the president of the People’s Republic of Korea, who died in 1994, his childhood story is presented to every North Korean in multi-volume biographies as teaching material for the Juche philosophy he founded. Episodes from this fake biography adorn the country’s empty highways in monumental paintings. And are performed in stage revues. Many of these episodes use elements from Christian folklore: at the birth of the future dictator, a star hovers over the hut, little Kim Il Sung turns mud into sparrows that fly away, as in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, and as a thirteen-year-old he presents his concept of an autonomous future, the Juche, in a party hall of the nationalists fighting against the Japanese occupation.

What Herbert Marcuse called the “longing for the wholly other” gives even these texts supported by state violence an obvious attractiveness. But Luke warns against this: when he has Jesus remind Mary of his true Father, earthly concerns lose their meaning – the secular “wholly other” contradicts the idea of the process of salvation that gives the Gospel its meaning. Mary had to experience this in the gentle warning of her son.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).