Der Friede sei mit dir

BWV 158 // For the Third day of Easter

(May peace now be with thee) for bass, vocal ensemble, oboe, strings and basso continuo

Bach’s third bass cantata, BWV 158, is often to be found on CD compilations together with the famous “Kreuzstab” and “Ich habe genug” bass cantatas, and while this makes for most sensible programming, BWV 158 generally seems to come off as the poor cousin of the trio. Indeed, the cantata’s disparate themes of rejection of the world and the Easter message lends the composition a somewhat bizarre tension, a circumstance that may well be explained by the work’s divergent manuscripts, which survive only in transcripts by Bach’s students. Nevertheless, the cantata’s extant sources suggest that it was initially written for the Feast of Purification (Simeon’s Day, 2 February), and then reassigned in part and reorchestrated for the Third Day of Easter.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Bass

Peter Harvey

Choir

Soprano

Noëmi Sohn Nad

Alto

Antonia Frey

Tenor

Raphael Höhn

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Ingo Müller

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Hans Rudolf Merz

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/04/2015

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

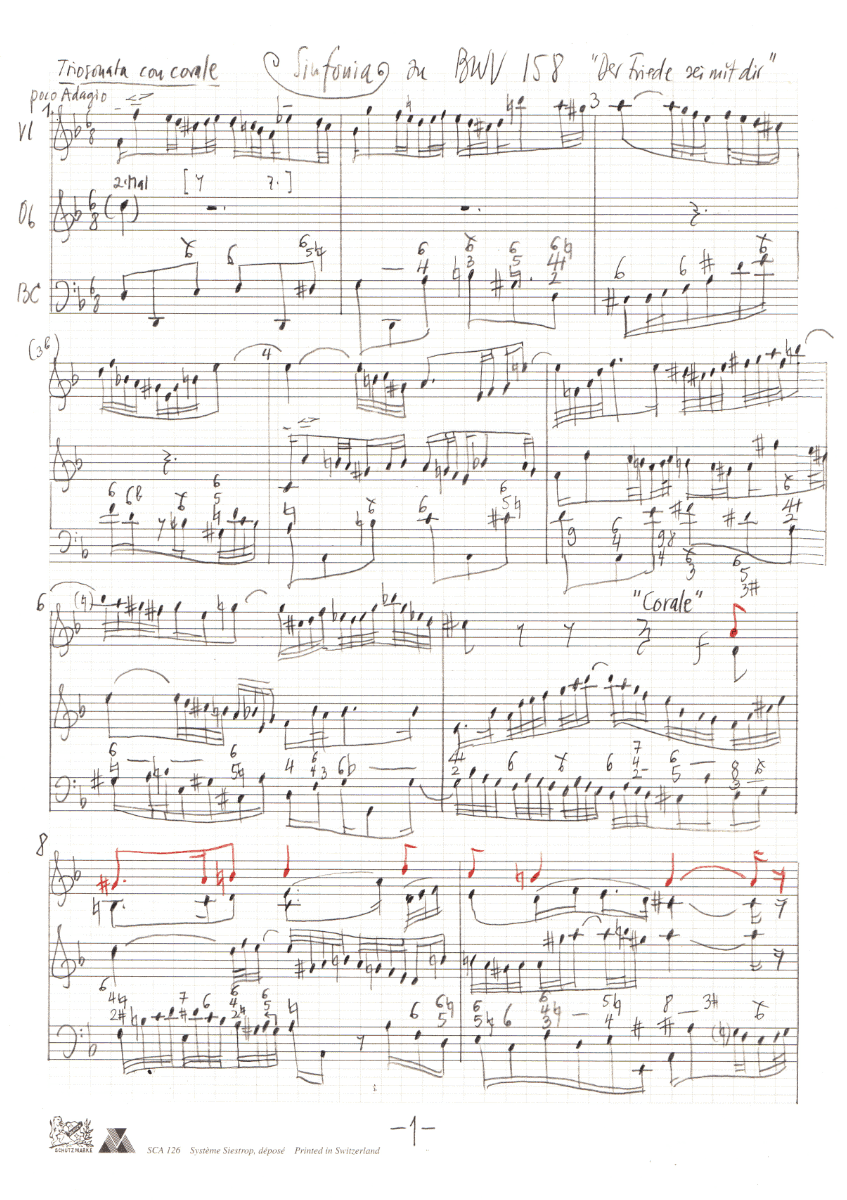

Composer of sinfonia No. 1

Rudolf Lutz

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–3

Poet unknown, with

hymn by Georg Albinus interpolated in No. 2, 1649

Text No. 4

Martin Luther, 1524

First performance

Possibly on 3rd Day of Easter,

(27 April) 1734 (?)

In-depth analysis

Rudolf Lutz’s addition of a chorale-based sinfonia resolves the unsatisfying musical gaps in this constellation by rounding out and clarifying the Easter relevance of the cantata in a way that was not accomplished by Bach’s contemporaries.

The expansive recitative is set in a style that would be well suited to argumentatively developing the bible dictum of the lost tutti movement, and melds the blessing “May peace now be with thee” – pronounced in arioso style three times throughout the movement – with a memorable recitation describing Easter as the victory of the lamb and the liberation from oppressive law. Here, the key word “peace” is lent a broad interpretation, one that suggests the drying of all tears, the deliverance to a state free of falsity and sorrow, and thus to a meeting between God and man in his natural human state; in this setting, Christ does not speak through the mouth of a priestly intercessor, but rather, “he saith himself to thee” and thus directly to all persons of good will.

The aria and chorale “World, farewell, of thee I’m weary” links the bass’s world-weary rejection of earthly turmoil with a soprano setting of the chorale bearing the same name by Johann Georg Albinus (1649). But in contrast to many other such double movements, Bach does not add the chorale text here to comment on the freely versed text, thus giving voice at a second level to what may have been unutterable by the solo voice. Rather, both text levels here are identical in a way that summons an extraordinary intensity against the backdrop of the Passion. The actual “star” of this setting, however, is the solo violin, which, like in the aria “Keep thou, my heart now, this most blessed wonder” of the Christmas Oratorio, reveals Bach’s special relationship to the instrument that, as a concertmaster, he had fully mastered. Here, the wise naivety and noble cantilena of the violin part lends the movement a heavenly dimension, giving poignant musical expression to earthly suffering and the worthy strivings of humankind to attain a more perfect state.

The bass recitative “O Lord, now govern all my thoughts” returns again to the farewell metaphor of Simeon’s Day and expresses final submission to God’s will. Here, the faithful are not only willing, but sincerely relieved, to lay down their earthly woes and take up the “heavenly crown“ of the righteous. The somewhat abrupt transition to the closing chorale “Here is the proper Easter lamb“ is probably the result of the cantata’s patchy source materials and revision – and yet it can still be appreciated as a theologically sound interpretation of transcendent bliss.

Libretto

1. Rezitativ (Bass)

Der Friede sei mit dir,

du ängstliches Gewissen!

Dein Mittler stehet hier,

der hat dein Schuldenbuch

und des Gesetzes Fluch

verglichen und zerrissen.

Der Friede sei mit dir,

der Fürste dieser Welt,

der deiner Seele nachgestellt,

ist durch des Lammes Blut

bezwungen und gefällt.

Mein Herz, was bist du so betrübt,

da dich doch Gott durch Christum liebt?

Er selber spricht zu mir:

Der Friede sei mit dir!

2. Arie (Bass) und Choral (Sopran)

Welt, ade, ich bin dein müde,

Salems Hütten stehn mir an;

Welt, ade, ich bin dein müde,

ich will nach dem Himmel zu,

wo ich Gott in Ruh und Friede

ewig selig schauen kann.

da wird sein der rechte Friede

und die ewig stolze Ruh.

Da bleib ich, da hab ich Vergnügen

zu wohnen,

da prang ich gezieret mit himmlischen Kronen.

Welt, bei dir ist Krieg und Streit,

nichts denn lauter Eitelkeit;

in dem Himmel allezeit

Friede, Freud und Seligkeit.

3. Rezitativ (Bass)

Nun Herr, regiere meinen Sinn,

damit ich auf der Welt,

so lang es dir mich hier

zu lassen noch gefällt,

ein Kind des Friedens bin,

und laß mich zu dir aus meinen Leiden

wie Simeon in Frieden scheiden!

Da bleib ich, da hab ich Vergnügen

zu wohnen,

da prang ich gezieret mit himmlischen Kronen.

4. Choral

Hier ist das rechte Osterlamm,

davon Gott hat geboten;

das ist hoch an des Kreuzes Stamm

in heißer Lieb gebraten.

Des Blut zeichnet unsre Tür;

das hält der Glaub dem Tode für;

der Würger kann uns nicht rühren.

Alleluja!

Rudolf Lutz’s addition of a chorale-based sinfonia resolves the unsatisfying musical gaps in this constellation by rounding out and clarifying the Easter relevance of the cantata in a way that was not accomplished by Bach’s contemporaries.