Komm, du süße Todesstunde

BWV 161 // For the Sixteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Come, O death, thou sweetest hour) for alto and tenor, vocal ensemble, flute I+II, strings and continuo.

First performed in 1716, cantata BWV 161 (“Come, O death, thou sweetest hour”) is distinguished by a fresh style and sensitive interpretation that clearly indicate its composition during the “cantata spring” of Bach’s tenure as concertmaster of the Hofkapelle in Weimar. A later version also survives, with “modernised” orchestration (such as transverse flutes doubled by violins in place of recorders) that may reflect Bach’s changed circumstances during his Leipzig period. The later owner of the manuscript, Carl Friedrich Zelter, described the cantata as a “charming little masterpiece” although, as a child of the Enlightenment, he also wondered at the discrepancy between the bleakness of the poetry and the cheerful air of the music.

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Herr, Gott, du bist unsre Zuflucht für und für. Ehe denn die Berge wurden und die Erde und die Welt geschaffen wurden, bist du, Gott von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit, der du die Menschen lässest sterben und sprichst: «Kommt wieder, Menschenkinder!» Denn tausend Jahre sind vor dir wie der Tag, der gestern vergangen ist, und wie eine Nachtwache. – Lehre uns bedenken, dass wir sterben müssen, auf dass wir klug werden.

Darum bitte ich, dass ihr nicht müde werdet um meiner Trübsale willen, die ich für euch leide, welche euch eine Ehre sind. Derhalben beuge ich meine Kniee vor dem Vater unseres Herrn Jesu Christi, der der rechte Vater ist über alles, was da Kinder heisst im Himmel und auf Erden, dass er euch Kraft gebe nach dem Reichtum seiner Herrlichkeit, stark zu werden durch seinen Geist an dem inwendigen Menschen, dass Christus wohne durch den Glauben in euren Herzen und ihr durch die Liebe eingewurzelt und gegründet werdet, auf dass ihr begreifen möget mit allen Heiligen, welches da sei die Breite.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

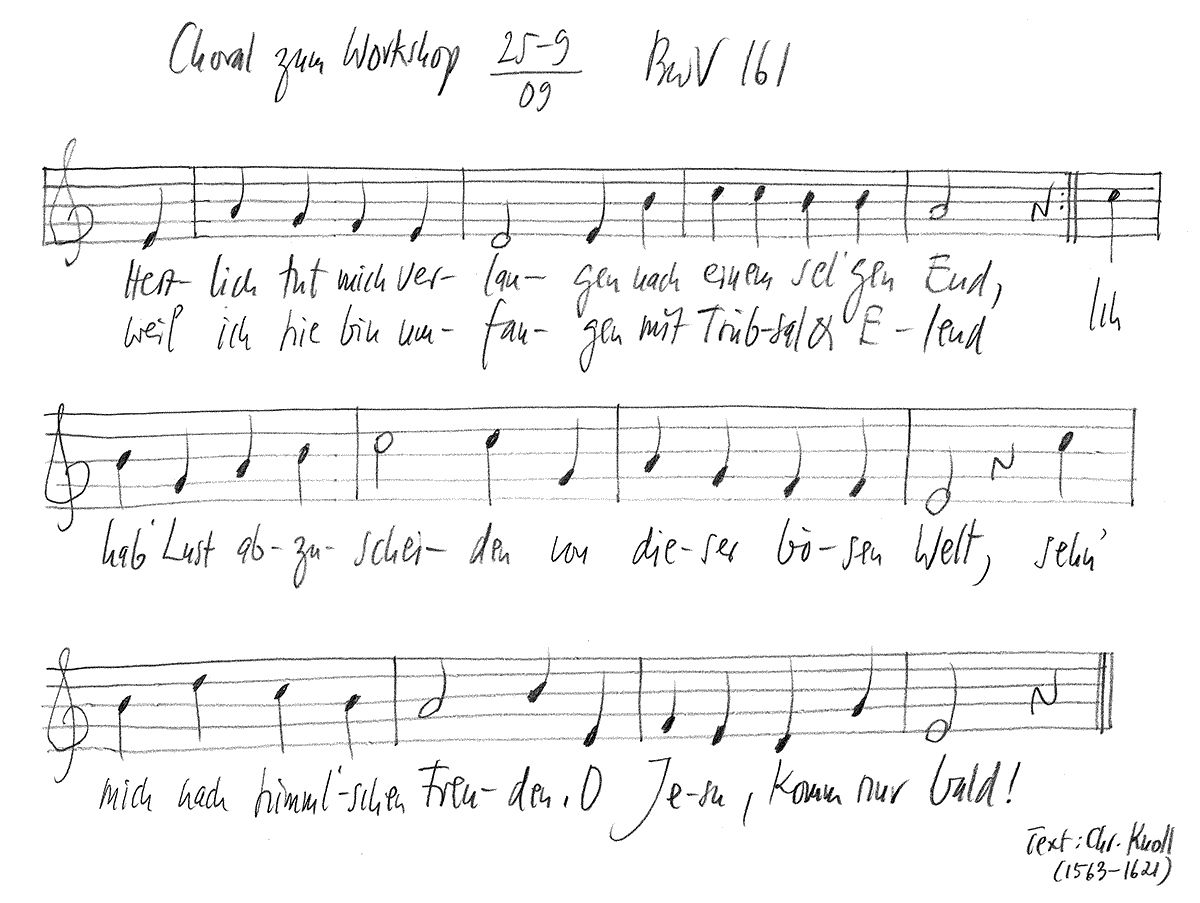

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Jennifer Rudin, Noëmi Tran Rediger

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Matthias Ebner, Fabrice Hayoz, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Fanny Tschanz

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Transverse flute

Claire Genewein, Martin Skamletz

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Alex Rübel

Recording & editing

Recording date

09/25/2009

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–5

Salomo Franck (1659–1725)

Text No. 1, 6 (Choral)

Christoph Knoll (1563–1621)

First performance

Sixteenth Sunday after Trinity,

27 September 1716

In-depth analysis

The introductory movement is based on a cryptic theological reference that links the fervent longing for one’s own death to the sweet honey that Samson harvested from the mouth of a slain lion (Judges 14). Capturing this mood, Bach opens the movement with a delicate trio setting for two transverse flutes and basso continuo whose head motive transforms even the notoriously lamenting sighs of these instruments into a tender cantilena. The alto soloist then enters, supplemented by a chorale melody played on the organ in bright, sesquialtera registration; in the later version the chorale insertion is instead scored for soprano, who sings the first verse “Heartfelt is now my yearning”.

The tenor recitative then answers with a veritable tirade against the world. Capitalising on the wordplays typical of librettist Salomo Franck, such as “Lust ist Last” (delights are burdens), the movement exposes various forms of deceptive beauty and false security, in which even the much-discussed comet that appeared around 1700 and was widely seen as a godly omen garners a mention. The recitative ends with an arioso passage alluding to the dictum “I desire to depart and be with Christ” from St Paul’s epistle to the Philippians, a passage that Buxtehude, Bach’s teacher, also set to music.

The tenor aria is underscored by a string ensemble, whose discreet rhythmic impulse shifts all emphasis onto the key word of “Verlangen” (desire); throughout the course of the movement, the vocal line seems to emerge from this material. The setting is graced by a particularly well-set viola part, and requires soulful music-making across complex phrasing and dramatic rests. Despite the lustre of the tenor lines, the lowness of the register restrains any brilliance – even in the vibrant middle section, the music remains a modest and insightful prayer.

The alto recitative is set as an accompagnato that employs the distinctive timbral combination of strings and transverse flutes. Throughout the setting, a veritable scene evolves that traverses from images of fear, to the knell of death and fanfares of resurrection. The rendering of the “sleep of death” is particularly effective here, with the sustained chords by the transverse flutes allowing the loving hands of the saviour to extend into the music.

This is followed by an enchanting ensemble movement in which Bach melds a rhythmic, speech-like string motive and a fluid transverse flute line with such finesse that the contrasting effect is enhanced rather than blurred. With its swirling wind parts and basset-style string writing the music is similar to the closing movements of the Brandenburg Concerti that Bach was soon to commence work on. The transparent choral setting, with its reflective style of voice pairings, creates the effect of an aria for four voices and, in various passages, anticipates Bach’s Passion compositions. By virtue of short phrases that progress to clear cadences, the movement possess a tangible charm that Bach does not attain again until composing his courtly occasional cantatas of the 1730s.

While the timbral quality of the transverse flute effectively expresses both life’s transience and a pastoral vision, the closing chorale brings any wavering to a brutal close with its pronouncement on the end of human existence that necessarily precedes any access to paradise. Here, the extremely subdued vocal setting is supplemented by a transverse flute obbligato, whose floating whirls can only be interpreted as the winds of eternity. In contrast to the untroubled equanimity of the preceding choral aria, this movement presents an unadorned view of the open grave: in this infinitely sad setting, we hear note for note that despite all rhetoric on the afterlife, the loss of parents, friends and children was as acutely painful in 1725 as it is today.

Libretto

1. Arie (Alt) und Choral (Sopran)

Komm, du süße Todesstunde,

da mein Geist

Honig speist

aus des Löwen Munde.

Mache meinen Abschied süße,

säume nicht,

letztes Licht,

daß ich meinen Heiland küsse.

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Welt! Deine Lust ist Last!

Dein Zucker ist mir als ein Gift verhaßt!

Dein Freudenlicht

ist mein Komete,

und wo man deine Rosen bricht,

sind Dornen ohne Zahl

zu meiner Seele Qual.

Der blasse Tod ist meine Morgenröte,

mit solcher geht mir auf die Sonne,

die Herrlichkeit und Himmelswonne.

Drum seufz ich recht von Herzensgrunde

nur nach der letzten Todesstunde!

Ich habe Lust, bei Christo bald zu weiden,

ich habe Lust, von dieser Welt zu scheiden.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Mein Verlangen

ist, den Heiland zu umfangen

und bei Christo bald zu sein.

Ob ich sterblich’ Asch und Erde

durch den Tod zermalmet werde,

wird der Seele reiner Schein

dennoch gleich den Engeln prangen.

4. Rezitativ (Alt)

Der Schluß ist nun gemacht,

Welt, gute Nacht!

Und kann ich nur den Trost erwerben,

in Jesu Armen bald zu sterben;

er ist mein sanfter Schlaf.

Das kühle Grab wird mich mit Rosen decken,

bis Jesus mich wird auferwecken,

bis er sein Schaf

führt auf die süße Lebensweide,

daß mich der Tod von ihm nicht scheide.

So brich herein, du froher Todestag,

so schlage doch, du letzter Stundenschlag!

5. Chor

Wenn es meines Gottes Wille,

wünsch ich, daß des Leibes Last

heute noch die Erde fülle

und der Geist, des Leibes Gast,

mit Unsterblichkeit sich kleide

in der süßen Himmelsfreude.

Jesu, komm und nimm mich fort!

Dieses sei mein letztes Wort.

6. Choral

Der Leib zwar in der Erden

von Würmen wird verzehrt,

doch auferweckt soll werden,

durch Christum schön verklärt,

wird leuchten als die Sonne

und leben ohne Not

in himml’scher Freud und Wonne.

Was schadt mir denn der Tod?