O heilges Geist- und Wasserbad

BWV 165 // For Trinity Sunday

(O Holy Spirit’s water bath) for Trinity (First Sunday after Pentecost), for soprano, alto, tenor and bass; strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Judith von der Goltz, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Sonoko Asabuki, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Helen Schüngel-Straumann

Recording & editing

Recording date

19/03/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

16 June 1715, Weimar

Text

Salomo Franck (movements 1–5)

Ludwig Helmbold (movement 6)

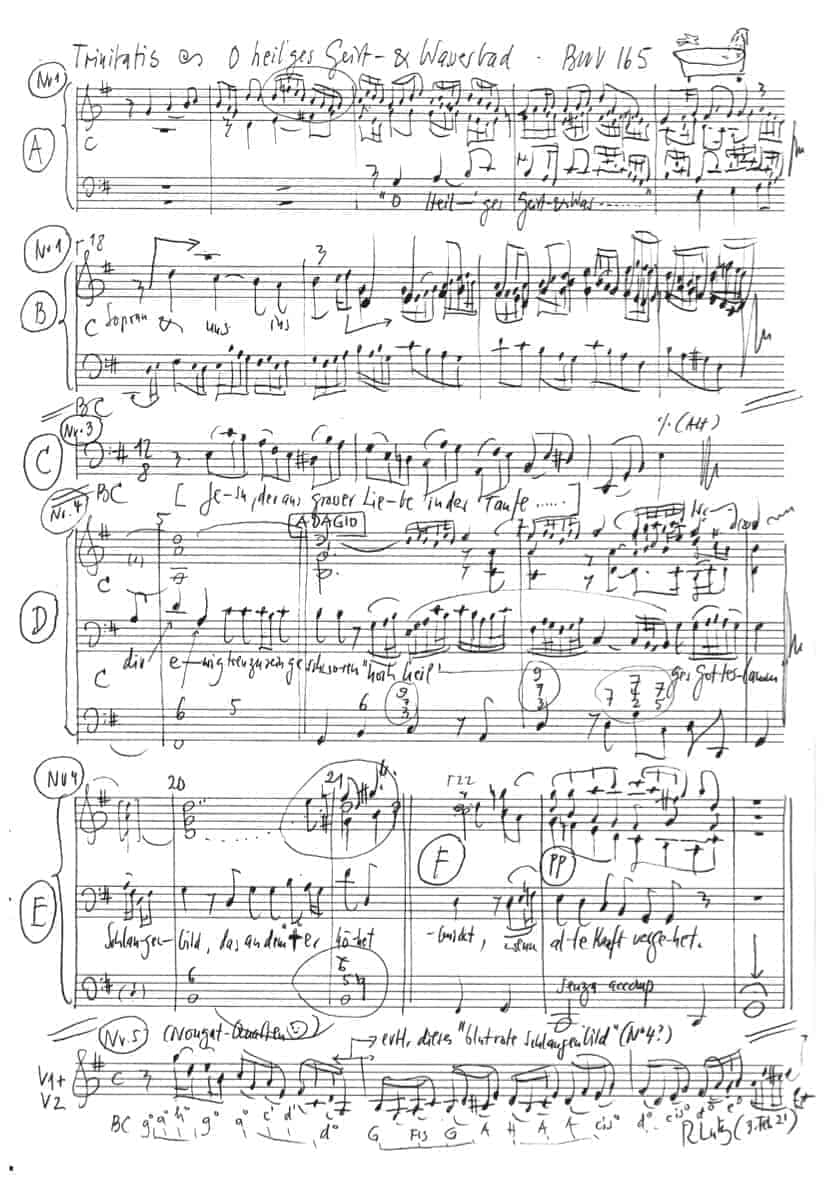

In-depth analysis

At first glance, cantata BWV 165 “O heilges Geist- und Wasserbad” (O Holy Spirit’s water bath 165) may appear somewhat uninspired compared to Bach’s other works for Trinity Sunday, lacking as it does a powerful opening tutti movement and being orchestrated for strings only. Nonetheless, the cantata, which was most likely composed in 1715 in Weimar and probably adapted in 1724 for performance in Leipzig, embodies the distinct qualities of Bach’s Weimar cantata style; in addition to the light transparency of sound, there is a strong focus on the libretto by Salomo Franck, which here, as ever, is distinguished by its particular eloquence and powerful imagery.

In the introductory soprano aria, the strict, fugue-like style of the string entries is combined with an elegant flexibility in their melodic arcs to capture both the earnest nature of the narrative as well as the healing sweetness of the transformative sacrament of baptism. To an extent, this euphonious setting emerges from nowhere, engendering a palpable sense of something coming into being – a “neues Leben” (new life) that unfolds bar by bar and is thus entered in the “score of eternity”.

In the bass recitative, the librettist dramatically contrasts “verdammte Adamserben” (Adam’s cursed offspring) with the “seliger Christ” (blessed Christian), thus vividly manifesting the merciful – albeit undeserved – gift of being a child of God. The text is abundant in possibility, and Bach skilfully sets every line with a keen sense of drama and a rich harmonic vocabulary. The idea to stress the word “selig” (blessed) with a dissonant seventh interval and thus pave the way for the total union with Christ in the brightest key of C major is nothing short of genius – yet it is precisely these bold strokes, woven masterfully throughout the vocal line, that render Bach’s recitatives so convincing, making even the most profound statements readily clear to both ear and heart.

It is therefore unsurprising that the following aria, scored solely for an alto soloist and continuo, succeeds in evoking a scene of elegiac beauty. The floating 12⁄ 8 metre and gentle continuo triads furnish the vocal soloist with the backdrop for an introspective prayer that, in a clouded E minor tone, also expresses Jesus’ powerful act of love and our lifelong work to please God.

The following “Recitativo con strumenti” interrupts such premature complacency by following up the opening praise for the “hochheiligs Gotteslamm” (holy lamb of God) with forceful self-recrimination for having repeatedly broken the “Taufbund” (bond of baptism). The ensuing appeal for mercy, underscored by a ceremonial string part, culminates in the double metaphor of the serpent, which was first responsible for humanity’s fall from grace and which Moses later raised on a cross as a symbol of healing. The way Bach transforms the snake’s deadly venom into the ultimately curative medicine of the viaticum is at once fully an interpretation of the baroque era, yet timeless in the gentle power of its solace.

The following tenor aria, too, seems beholden to this remarkably bold image of Christ as the “Heilsschlänglein” (healing serpent), with unisono violins darting up and down in endless lines of paired slurs set over relaxed continuo quavers; in the setting, Bach evidently drew inspiration from Franck’s penchant for contrastive pairs and word play. As throughout the entire cantata, comparatively few bars suffice – with a judicious use of musical devices – to paint a precise image that haunts listeners long after the music ceases.

In good Lutheran fashion, the closing hymn verse from Ludwig Helmboldt’s chorale “Nun lasst uns Gott dem Herren” (Now let us thank God, the Lord, 1575) summarises the cantata’s message of the word of God, baptism, and the Eucharist. In this setting, the accent on the uplifting “Heiliger Geist” (Holy Spirit) complements the skilfully integrated passing notes that, as with the organ interlude we chose to add for this recording, imbue the simple chorale with an inner radiance.

Libretto

1. Arie — Sopran

O heilges Geist und Wasserbad,

das Gottes Reich uns einverleibet

und uns ins Buch des Lebens schreibet! O Flut, die alle Missetat

durch ihre Wunderkraft ertränket

und uns das neue Leben schenket!

O heilges Geist und Wasserbad!

2. Rezitativ — Bass

Die sündige Geburt verdammter Adamserben

gebieret Gottes Zorn, den Tod und das Verderben.

Denn was vom Fleisch geboren ist,

ist nichts als Fleisch, von Sünden angestecket,

vergiftet und beflecket.

Wie selig ist ein Christ!

Er wird im Geist- und Wasserbade

ein Kind der Seligkeit und Gnade.

Er ziehet Christum an

und seiner Unschuld weiße Seide,

er wird mit Christi Blut, der Ehren Purpurkleide,

im Taufbad angetan.

3. Arie — Alt

Jesu, der aus großer Liebe

in der Taufe mir verschriebe Leben,

Heil und Seligkeit,

hilf, daß ich mich dessen freue

und den Gnadenbund erneue

in der ganzen Lebenszeit.

4. Rezitativ — Bass

Ich habe ja, mein Seelenbräutigam,

da du mich neu geboren,

dir ewig treu zu sein geschworen,

hochheilges Gotteslamm;

doch hab ich, ach! den Taufbund oft gebrochen

und nicht erfüllt, was ich versprochen,

erbarme, Jesu, dich

aus Gnaden über mich!

Vergib mir die begangne Sünde,

du weißt, mein Gott, wie schmerzlich ich empfinde

der alten Schlangen Stich;

das Sündengift verderbt mir Leib und Seele,

hilf, daß ich gläubig dich erwähle,

blutrotes Schlangenbild,

das an dem Kreuz erhöhet,

das alle Schmerzen stillt

und mich erquickt, wenn alle Kraft vergehet.

5. Arie — Tenor

Jesu, meines Todes Tod,

laß in meinem Leben

und in meiner letzten Not

mir für Augen schweben,

daß du mein Heilschlänglein seist

vor das Gift der Sünde!

Heile, Jesu, Seel und Geist,

daß ich Leben finde!

6. Choral

Sein Wort, sein Tauf, sein Nachtmahl

dient wider allen Unfall,

der heilge Geist im Glauben

lehrt uns darauf vertrauen.

The Paradise Serpent

Dear listeners

In the sung text by Bach there is a snake that tries to seduce people in the garden (paradise). It is therefore a negative actor in the so-called paradise story; it is an animal, but it can speak and is described as “wise”. However, this would be better translated as “cunning/cunning” than “all the beasts of the field that YHWH-God had created”. A positive expression like “wisdom/cunning” is not used, so one can already guess that she is up to no good.

The text with the serpent-woman conversation is a separate piece in Genesis 3 and has roots in traditions from the Near East. There, there are numerous creation stories that always revolve from the creation of human beings by the gods to their destruction in a great flood. Numerous such myths are centuries older than the account in the Bible. They all have the same arc of tension from a good creation by the gods and then, because of human transgressions, to a great flood that again destroys all humans except one who is saved.

In our story the woman is addressed by the serpent, she wants to become wise, she promises herself that from the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.

The text reads exactly:

“But the serpent was more cunning than all the beasts of the field which YHWH-God had made. And she said to the woman, ‘Did God really say you must not eat of any tree of the garden?’ Then the woman said to the serpent, ‘Of the fruit of the trees of the garden we may eat; only of the fruit of the tree in the midst of the garden hath God said: ‘Do not even touch it, or you will die! Then the serpent said to the woman, ‘By no means will you die, but God knows that as soon as you eat of it your eyes will open and you will be like God, knowing what is good and what is evil’. And the woman saw that it was good to eat of the tree, and that it was lovely to look upon, and desirable, because it made one wise; and she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband beside her, and he did eat also. Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they put fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.” (Genesis 3:1-7)

So this is about “good and evil” and becoming wise. The woman’s desire for wisdom is certainly not evil. But the serpent unsettles the woman and drives her up the garden path. Cunningly, he asks the question “Did God really say…?” and thus forces the woman to defend God. They are only not allowed to eat from a tree in the middle of the garden. A word like “seduction” does not appear in the text, later it only says that the serpent “deceived” the woman.

After the people have eaten, however, they do not recognise their greater cleverness, but only their nakedness. Thus the serpent has wriggled around the two concepts of “good and evil” to achieve its goal.

How, in fact, can evil enter into the harmonious paradise? This is a question that cannot be solved, an inexplicable event. By the way, the serpent did not lie at all, people do not die after eating the fruit, they are only driven out of the garden later.

The serpent is a mythologically very important animal, it was an extremely colourful figure in the Near East centuries before our Bible text was written. It can stand for good, but also for evil, for life, but also for death. In the story of paradise, however, it has a purely negative function. Theologically, however, it is important to note that the culprit in the Bible is clearly the serpent.

In later times, especially throughout Christian history, the serpent has been interpreted as the devil/Satan. There is nothing of this in Genesis 3, the text explicitly states that it is a creature of God. Instead of the serpent, the Christian story then blames Eve, the woman, for the transgression. As a temptress, as inferior, as subservient to man, as dangerous, etc., Eve has been denigrated, and this for almost 2000 years.

The Church Father Augustine was completely wrong here when he said that the devil, Satan, had turned to woman because she was the weaker, the more easily seduced. He would not have dared to approach man, the image of God. This conclusion, which is completely deviant from the ancient oriental tradition, has caused an immense amount of harm to women. – The word “Fall of Man” also comes from Augustine; this term is not found in the entire Hebrew Bible. Also in the story of paradise there is no word for “sin”, only in the following chapter Genesis 4, where the first man outside paradise, Cain, slays his brother Abel, is this term found for the first time. The terms sin, original sin and fall of man all come from Augustine’s interpretation of Genesis.

The consequences for a Christian image of women were catastrophic; this has only been set right since the 20th century. The name Eve – Hebrew chawwah – comes from chay = life and it is said at the end of the chapter: “She is the mother of all living things.” This phrase is seen by many exegetes as a remnant of a goddess. The fact that the whole Hebrew Bible knows nothing of a “Fall” or original sin confirms the Jewish tradition. There, such a negative interpretation for the woman does not occur. Rather, Eve is highly revered as “mother of us all” and chawwah is a popular female name in Israel. I cannot pursue this problem about the misogyny of the Christian tradition here, this would be a wide field, about which there is my Eve book.

The question that arises here is: Why does the serpent only speak to the woman, when the man is next to her? It has often been noticed that the man seems like an extra, he doesn’t say a word in this whole scene, he just eats.

There are profound reasons for this in the oriental tradition: the woman as the one who passes on life is much more connected to life than the man. In a pre-scriptural time, the woman was the decisive person, everything depended on her, especially the continuity of humanity. It was a time when men were still unaware of their own part in the beginning of life. At that time, the main goddesses were female, e.g. Innana in Mesopotamia. It was only between 4000 and 3000 BC that the main goddesses were degraded to wives of the gods. The various changes did not happen suddenly, of course, but in long processes. Snake goddesses as well as mother goddesses existed until Greek and Roman times. In Egypt, the earth god Geb had a snake’s head, and in Greece snake goddesses were still sold as figurines until more recent times. Snakes and snake goddesses were also associated with a tree everywhere, especially in Egypt.

In Mesopotamian tradition, the snake plays very different roles. There is older evidence, in the Ancient Near East and also in Egypt, that there it is responsible not only for death and evil, but also for life.

The mythical serpent was also always closely associated with the tree. The Tree of Life, which stands in the middle of the Garden of Eden, is a relic of this Mesopotamian tradition. Whoever eats of its fruit acquires eternal life. In the story of paradise this tree plays no role, there it is the tree of the “knowledge of good and evil”. This is the tree from which people are forbidden to eat. So there were actually two trees in the middle of the garden, the “tree of life” from the ancient Orient and the tree of the “knowledge of good and evil”, which was important for the authors of the story of paradise. This is difficult to understand for today’s logic, but it was normal for the thinking of that time: one leaves the traditional and simply adds the new.

How does this positive role of the serpent in Mesopotamia manifest itself long before our biblical story? Whoever finds this tree of life and eats of its fruit acquires eternal life. Man has changed very little in the last 4000-5000 years. Everyone wanted to live longer, if possible even eternally (like the gods). So there were many means of prolonging one’s life – think that the average mortality was little more than 30 years – there were ointments or waters into which one could climb and then emerge rejuvenated. Cosmetic surgery did not yet exist, but all kinds of means to prolong life did. But whoever found the “tree of life” would gain eternal life.

So what does all this have to do with the snake? In the last 150 years, a wealth of texts from the Near East have been found and deciphered. People always wanted to know where they came from, so there are numerous creation stories, named after their beginnings: Enuma Elish, the Athrachasis myth and many others. I can only bring one example here that fits our theme, namely from the Epic of Gilgamesh. This scripture, of which there are many variants, is also quite well known. In it, there is a scene with the serpent that is very revealing for the question of life and death. This scene suggests that the snake was seen both negatively and positively. The hero of the story, a demigod, is desperate to find the tree of life in order to live forever. He cannot come to terms with human finitude. So he sets out on his journey, has many adventures and encounters with other people, then he finally gets lucky and finds the Tree of Life. He picks from its leaves. But because he is so tired from his many hardships and adventures, he sits down on the edge of a well, puts the herb beside him and falls asleep. Then a snake crawls up out of the well and eats the herb away from him. When he awakes, he is inconsolable… now the snake has attained eternal life! (Gilgamesh XI/304 f.)

How can it be that the snake was understood as a symbol of life, even eternal life? It was a very dangerous animal, especially in the heat of the Near East, so how could it become a symbol of eternal life and health? – There are several explanations. One obvious reason is that people hardly ever found dead snakes, which hid in caves when they were about to die. What people did find, however, were skins that dried in the sun. From this they concluded that the snakes always rejuvenated themselves and never died. This view lasted for a very long time: the snake as a symbol of health and long life! In Hellenistic times, it became the Aesculapian snake, which lasted for more than 2000 years. Today, you will hardly find a pharmacy that does not have an Aesculapian snake coiled around a staff on its logo, symbolising health and long life.

There is even a passage in the Old Testament that confirms this positive view: In pre-exilic times, a bronze staff with a snake, the “brazen serpent”, stood in the Jerusalem temple. Whoever looked up to it became healthy. It was once erected by Moses, but later removed by an Israelite king.

The cantata also speaks of an elevated serpent on the cross – almost like the bronze serpent – as the beginning of the new time of salvation.

After the many positive occurrences of the mythical serpent, however, I have to come back to the everyday life of that time. There, the snake was an immensely dangerous animal. It crept up almost silently, it was treacherous and its venom was usually deadly. There are numerous mentions of the dangerous snake, I will just present one particular text here that makes this very starkly clear. – Just as humanity in many places had a narrative about the beginning, a creation story with a paradisiacal state, so there was also in each case a myth about an end time, eschatology, where everything then becomes harmonious and good again. A passage from the prophet Isaiah from the 8th century B.C. can prove this well.

“At the end of the days it will come to pass:

And the wolf shall dwell with the lamb

and the hyena shall lie down with the kid

and the lion will eat straw like the ox.

And the suckling shall feast at the hole of the viper,

and the infant shall stretch forth his hand unto the den of vipers…”

(Isaiah 11:6-8)

In this promise it is said that the infant can play carefree at the hole of the vipers! Like people, toddlers were not much different then than they are now. As soon as the little ones can crawl or walk, they have to feel the world everywhere. They especially love to stick their little fingers into hollows, holes and the like. In those days, they were mostly outdoors and not as sheltered as they are today. Today, responsible parents put lids over all sockets when the little ones crawl around in the house so that they do not come into contact with electricity. – The fact that the prophet Isaiah mentions the danger of the snake in connection with lions and hyenas confirms the dangerousness of this insidious creeping animal. There are no figures or statistics on how many infants died from snakebites at that time, in addition to the already high infant mortality rate. But there must have been a great many, otherwise the Prophet would not have listed them in such a prominent place.

So how is it that the same animal could become a symbol of both life and death and good and evil? We cannot resolve this discrepancy, it is a stark contrast – in French we would say: Les extrèmes se touchent – but at the same time they also belong closely together. It is the ambivalence of life and death, good and evil, which causes problems everywhere and cannot be completely explained anywhere. We have to endure this ambivalence, and every thinking person has to deal with it.

———————————

For further reading:

Helen Schüngel-Straumann: EVA – the first woman in the Bible: Cause of all evil? Paderborn, 2014

Othmar Keel: The Position of Women in the Narrative of Creation and the Fall. In: Orientation 39 (1975), pp. 74-76.

Silvia Schroer: The Branch Goddess in Palestine/Israel. In: Max Küchler/Christoph Uehlinger (eds.): Jerusalem. Texts – Images – Stones (NTOA 6). Fribourg/Göttingen, 1987, pp. 201-225.

Urs Winter: Woman and Goddess. Exegetical and Iconographic Studies on the Female Image of God in Ancient Israel and its Environment (OBO 53). Fribourg/Göttingen, 1983, 2nd ed., 1987

The Epic of Gilgamesh, several editions, e.g. Reclam.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).