Tue Rechnung, Donnerwort

BWV 168 // For the Ninth Sunday after Trinity

(Make a reck’ning! Thund’rous word) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, oboe d’amore I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo

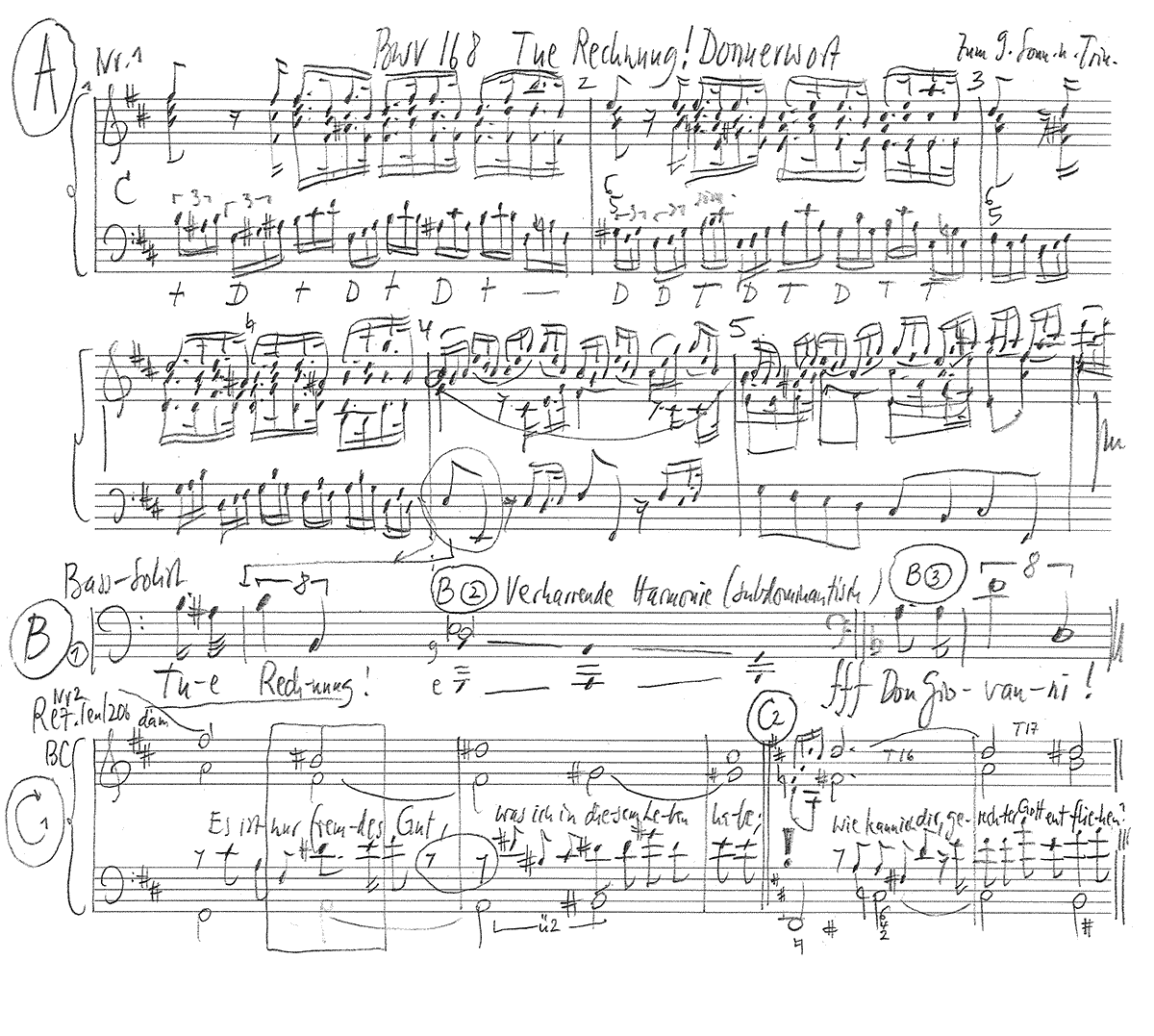

The cantata “Tue Rechnung! Donnerwort” (Make a reck’ning! Thunderous word), probably performed for the first time in 1725, numbers among Bach’s most dramatic compositions. Indeed, the work adopts an arresting tone from the opening phrase: in a setting of garish luminance – a musical pendant to the artworks of Bosch and Grünewald – the fiery introductory aria storms without warning, like a spiritual tax inspector, into the house of the soul, an image underscored by whipping dotted rhythms and hasty triplet passages alternating over a mercilessly driving continuo line.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen

Viola

Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Kerstin Kramp, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Rudolf Lutz

Harpsichord

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Martin Janssen

Recording & editing

Recording date

02/22/2013

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–5

Salomo Franck, 1715

Text No. 6

Bartholomäus Ringwaldt, 1588

First performance

Ninth Sunday after Trinity,

29 July 1725

In-depth analysis

The cantata “Tue Rechnung! Donnerwort” (Make a reck’ning! Thunderous word), probably performed for the first time in 1725, numbers among Bach’s most dramatic compositions. Indeed, the work adopts an arresting tone from the opening phrase: in a setting of garish luminance – a musical pendant to the artworks of Bosch and Grünewald – the fiery introductory aria storms without warning, like a spiritual tax inspector, into the house of the soul, an image underscored by whipping dotted rhythms and hasty triplet passages alternating over a mercilessly driving continuo line. For this text, in which a God enraged by the masses demands a reckoning, Bach could, with good conscience, breach his contract and compose an (otherwise forbidden) operatic scene of high drama that may well have knocked many a good citizen of Leipzig off their family church pew.

Accompanied by two oboe’s d’amore, the following tenor recitative, despite its tendency to a sublime tone, further exploits not only the accounting term of “errors”, but also, as the students of Leipzig were certainly wont to do, “The many things which God hath lent me”. It is thus probably no small coincidence that the movement bears resemblance to the Judas aria from the second version of the St John Passion (“Crush me, crush me you rocks and hills!”), also composed in 1725.

This is followed by an intense, erudite aria trio that provocatively underscores the financial imagery of the text: “Principal and interest also, These my debts, both large and small, Must one day be reckoned all”. In a tense, pedantic setting in F-sharp minor, Bach evokes the image of book-keeping in a “soul-based” economy; the implications were doubtlessly understood all too well in Leipzig – a city of merchants, trade fairs and all-pervasive corruptibility. In view of this chastisement for worshipping Mammon, it would be fair to interpret the scoring of oboes d’amore more as a symbol of business-like, cosmopolitan elegance than of godly courtship. And yet their unison scoring still awakens a glimmer of hope that a unifying, amicable settlement may ultimately be proffered…

This shift in focus is sustained in the bass recitative, whose central message of “live and despair thou not!” would seem nigh impossible following the raging summons from the heavenly tax officials. And yet, the poor sinner, plagued by his own conscience, now stands like a petrified bill-dodger whose unpayable bill has already been settled by an unknown benefactor. The notion that all debts are settled through Christ as guarantor and sacrificial lamb cuts to the heart of the Lutheran doctrine of justification through faith, which in this cantata is not so much spelt out as calculated through in a highly original fashion. Good deeds are no prerequisite for heavenly forgiveness; rather, forgiveness is the consequence of a good role model, as is underscored by the image of the just master. With this exhortation to “make prudent use of Mammon”, the librettist eschews a trite, non-binding critique of wealth, suggesting instead a pragmatic path of action that will do more than simply open the doors to “heaven’s shelters”.

The liberating strength inherent in this change in is expressed in the ensuing duet “Heart, break free of Mammon’s fetters” with inimitable skill. Characterised by an agitated main figure and clear vocal cues, the ostinato continuo and vocalists leave no doubt as to their resolve to cast off all earthly goods in order to die a gentle and blessed death. The fact that the three-part aria, comprising a disguised recapitulation, is already over after only 52 stirring bars is part of the interpretive plan: what is clear in the face of time and eternity, needs no further words – but rather strength and courage to change one’s ways. The closing chorale thus expresses its humble prayer for strength with a joyous spirit. All mention of bills and balances is past: the humble Christian, having shed the trappings of earthly wealth, stands in his hour of death alone and, but for his true faith, naked and poor before his creator.

Libretto

1. Arie (Bass)

Tue Rechnung! Donnerwort,

das die Felsen selbst zerspaltet,

Wort, wovon mein Blut erkaltet!

Tue Rechnung! Seele, fort!

Ach, du mußt Gott wiedergeben

seine Güter, Leib und Leben!

Tue Rechnung! Donnerwort!

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Es ist nur fremdes Gut,

was ich in diesem Leben habe;

Geist, Leben, Mut und Blut

und Amt und Stand ist meines Gottes Gabe,

es ist mir zum Verwalten

und treulich damit hauszuhalten

von hohen Händen anvertraut.

Ach! aber ach! mir graut,

wenn ich in mein Gewissen gehe

und meine Rechnungen so voll Defekte sehe!

Ich habe Tag und Nacht

die Güter, die mir Gott verliehen,

kaltsinnig durchgebracht!

Wie kann ich dir, gerechter Gott, entfliehen?

Ich rufe flehentlich:

Ihr Berge fallt! ihr Hügel, decket mich

vor Gottes Zorngerichte

und vor dem Blitz von seinem Angesichte!

3. Arie (Tenor)

Kapital und Interessen,

meine Schulden groß und klein

müssen einst verrechnet sein.

Alles, was ich schuldig blieben,

ist in Gottes Buch geschrieben

als mit Stahl und Demantstein.

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

Jedoch, erschrocknes Herz,

leb und verzage nicht!

Tritt freudig vor Gericht!

Und überführt dich dein Gewissen,

du werdest hier verstummen müssen,

so schau den Bürgen an,

der alle Schulden abgetan!

Es ist bezahlt und völlig abgeführt,

was du, o Mensch,

in Rechnung schuldig blieben;

des Lammes Blut, o großes Lieben!

Hat deine Schuld durchstrichen

und dich mit Gott verglichen!

Es ist bezahlt, du bist quittiert!

Indessen,

weil du weißt,

daß du Haushalter seist,

so sei bemüht und unvergessen,

den Mammon klüglich anzuwenden,

den Armen wohlzutun,

so wirst du, wenn sich Zeit und Leben enden,

in Himmelshütten sicher ruhn.

5. Arie (Duett Sopran, Alt)

Herz, zerreiß des Mammons Kette,

Hände, streuet Gutes aus!

Machet sanft mein Sterbebette,

bauet mir ein festes Haus,

das im Himmel ewig bleibet,

wenn der Erden Gut zerstäubet.

6. Choral

Stärk mich mit deinem Freudengeist,

heil mich mit deinen Wunden,

wasch mich mit deinem Todesschweiß

in meiner letzten Stunden;

und nimm mich einst, wenn dirs gefällt,

in wahrem Glauben von der Welt

zu deinen Auserwählten.