Gott, wie dein Name, so ist auch dein Ruhm

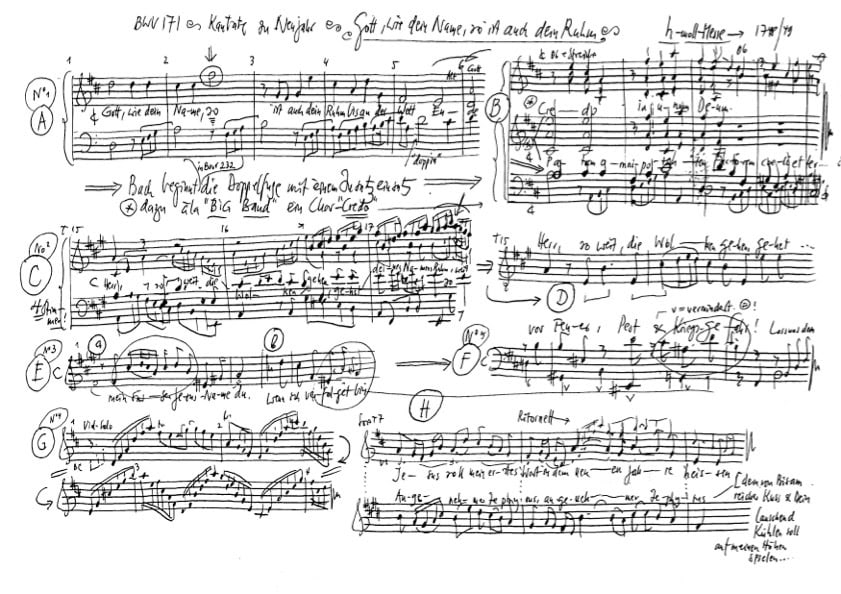

BWV 171 // New Year's Day (Feast of the Circumcision)

(God, as thy name is, so is, too, thy fame) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I-III, timpani, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Choir

Soprano

Maria Deger, Stephanie Pfeffer, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Rodrigo Carreto, Zacharie Fogal, Florian Glaus, Christian Rathgeber

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Johannes Hill, Israel Martins, Grégoire May, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler Gomes, Olivia Schenkel, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Claire Foltzer

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer

Timpani

Martin Homann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speakers

Anna Koim and Stefan Riedener

Recording & editing

Recording date

10/01/2025

Recording location

Trogen (AR) // Evang. Kirche Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

1 January 1729, Leipzig

Text

Christian Friedrich Henrici, 1728

Movement 1: Psalm 48:11

Movement 6: “Jesu, nun sei gepreiset”

(Johann Hermann, 1593), verse 2

Libretto

1. Chor

«Gott, wie dein Name, so ist auch dein Ruhm bis an der Welt Ende»

2. Arie – Tenor

Herr, so weit die Wolken gehen,

gehet deines Namens Ruhm.

Alles, was die Lippen rührt,

alles, was noch Odem führt,

wird dich in der Macht erhöhen.

3. Rezitativ – Alt

Du süßer Jesus-Name du,

in dir ist meine Ruh,

du bist mein Trost auf Erden,

wie kann denn mir

im Kreuze bange werden?

Du bist mein festes Schloß und mein Panier,

da lauf ich hin,

wenn ich verfolget bin.

Du bist mein Leben und mein Licht,

mein Ehre, meine Zuversicht,

mein Beistand in Gefahr

und mein Geschenk zum neuen Jahr.

4. Arie – Sopran

Jesus soll mein erstes Wort

in dem neuen Jahre heißen.

Fort und fort

lacht sein Nam in meinem Munde,

und in meiner letzten Stunde

ist Jesus auch mein letztes Wort.

5. Rezitativ – Bass

Und da du, Herr, gesagt:

Bittet nur in meinem Namen,

so ist alles Ja! und Amen!

So flehen wir,

du Heiland aller Welt, zu dir:

Verstoß uns ferner nicht,

behüt uns dieses Jahr

für Feuer, Pest und Kriegsgefahr!

Laß uns dein Wort, das helle Licht,

noch rein und lauter brennen;

gib unsrer Obrigkeit

und dem gesamten Lande

dein Heil des Segens zu erkennen;

gib allezeit

Glück und Heil zu allem Stande.

Wir bitten, Herr, in deinem Namen,

sprich: ja! darzu, sprich: Amen, amen!

6. Choral

Laß uns das Jahr vollbringen

zu Lob dem Namen dein,

daß wir demselben singen

in der Christen Gemein.

Wollst uns das Leben fristen

durch dein allmächtig Hand,

erhalt dein liebe Christen

und unser Vaterland!

Dein Segen zu uns wende,

gib Fried an allem Ende,

gib unverfälscht im Lande

dein seligmachend Wort,

die Teufel mach zuschanden

hier und an allem Ort!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Anna Koim and Stefan Riedener

A Cantata of the Earth: Cosmology according to Bach

‘What is the human? The human is a space, an opening,

where the universe celebrates its existence.’

Brian Swimme (born 1950)

1

When Johann Sebastian Bach worked in the evenings, he used candles or oil lamps. Ten of his twenty children died before they reached adulthood. At that time, very few people could read. It was not until a hundred years later that Charles Darwin would discover the principle of evolution. And another hundred years later, Georges Lemaître would recognise with amazement that the universe is not at rest, but is expanding.

How differently Bach must have experienced the world! Why are there crows, sitting on the ridge of the Leipzig Thomaskirche, the stars, the people? Why do these children die so early? And what is our function in the circle of this great event? It must have been a great mystery. Perhaps Bach sometimes stood at the graves of his children and rubbed his eyes.

And yet he had some kind of answer to all these questions. For Bach, God was the ground beneath everything, the unity in the whole, the horizon. Whatever Bach did, he saw as having its origin in God. And he did it with the aim of honouring and serving God. So Bach headed almost all his works with Jesu Juva, ‘Jesus help’. And he signed many of his scores with Soli Deo Gloria, ‘To God alone be the glory’.

The text of our cantata speaks from the heart of this worldview. God is the source of all that happens. He is the source of the community to which we ultimately belong – the community of Christians. And he justifies the purpose of our lives. ‘You are my life and my light, my honour, my confidence.’ – ‘Turn your blessing upon us, give peace at every end.’ – ‘Let us accomplish the year […] to praise the name of your, that we may sing in the Christian community.’

2

But what do these lines say to us? For some of us, Bach’s God is still the reason in this way today. And that is wonderful, of course. But for both of us, that is not true. For us, ‘Jesus’ is not the first and last word. What is our orientation? What is our reason; what community do we belong to; and what is our responsibility in it?

For many of us, the only horizon left is the human one. Our history goes back at most to our own family or country. And our responsibility stops at the latest with other people today. We hardly have any cosmological sense of something greater, something sacred. We are only rooted in ourselves.

This point of view is disastrous. In 2025, we no longer stand before the coffins of children snatched from us by an unfathomable fate. We stand before the bones of an entire planet that we are devastating in our aberration. ‘Everything that moves the lips, everything that still has breath, will increase you in power.’ We are hearing this cantata in the sixth great dying of the Earth’s history. We have the Earth in a stranglehold. The threats we create are even greater than ‘fire, plague and war’. And we don’t even rub our eyes. We wash our hands and look the other way, plunging into a gaping abyss. And how far our feelings reach – whether they stop at humans or include a larger circle – could determine how brutally we fall and how much we take with us.

So what can guide us – if not Bach’s God and not simply man?

3

Today, we know scientifically where everything comes from. This universe was born fourteen billion years ago in a great, silent flaring up of energy, matter, space and time. The carbon, calcium and iron that we are made of were formed in stars over billions of years of work, and hurled into space when the stars died. We are descendants of the stars. We are what we are because the sun burns itself into light every second; because four billion years ago the first cell was brought to life; because over millions of years our ancestors were exposed to the pull of the earth, the mountains, the winds, the light, and so our bones and our perception were formed. And still the stars explode around us and space expands, giving birth to the universe anew.

In this great birth, the origin is simple. This expanding universe is the source of everything. In the forest of Trogen, a deer lowers its head to drink at a puddle. The crows in Leipzig flap from St Thomas’s Church into the shimmering sky. The Earth turns towards the sun and turns away from it. Everything that exists is a form of the universe – a way in which it expresses itself. Everything that happens is part of the unfolding of this One.

Our ‘gift for the new year’ is this grand story. It is our story, each of ours. To open ourselves to this broad horizon can carry and orient us.

4

So this cantata also begins fourteen billion years ago. For its existence, too, atoms, galaxies and planets are needed. It needed the attempts of trillions of creatures before us. And these were only possible through the sun’s unceasing bestowal. We have the sun to thank for this cantata, the bacteria, the blackbirds. It is not simply Bach’s cantata. It is a cantata of the earth, of the Milky Way. It is an expression of the whole. In this music, the universe celebrates itself in musical form. And in the same way, it is not just our hearing. We too are a mode of existence of the whole. It is the universe that hears through us. Even at this moment, we are dependent on the whole cosmic process. Without the work of the ocean currents, the Earth’s magnetic field, and the earthworms, we would not be able to sit here.

Once I stood in front of a rock face at sunset. The clouds in the sky glowed, and so did the heather on the slopes. Two falcons flew over the wall, called out to the sky and plunged through the air. We were all at home on these slopes. We were all signatures of this wild, glowing, dancing cosmos.

Our community is thus larger than our small family, than the community of Christians, larger still than humanity. It is the community of all the components of the universe: the longhorn beetles, the granite boulders, the moons of Jupiter. The ‘you’ that we address at the beginning of this year and that catches us in our bottomless fall is this unity of the cosmos. And the ‘we’ encompasses all forms of being in it.

5

And what role do we humans play in this great community? Within us, the Earth has produced beings through whom the universe can consciously experience, reflect and celebrate. If we do not honour the universe, no one and nothing will. And then it lies there in its splendour and is not recognised – like a child who learns to walk and is not seen, who begins to speak and is not heard. And so we feel a responsibility akin to Bach’s: to marvel, to honour, to serve – right now, in the great collapse of the Earth community. That is our task. And could there be a more beautiful one?

Bach fulfilled this task with consummate mastery. In his work, he celebrates our rich universe of moths and mosses, buffaloes, clouds and stardust. At least, that’s how we can hear it, too.

And how do we face up to this responsibility – we who are not Bach? When we open ourselves to the cosmic dimension of our existence, everything is placed in a larger framework. It is a shattering experience. Our destruction of the earth is a cosmic offence. It is a failure to fulfil our role in the whole. We need a close relationship with the universe. One day we will have to become present for the Earth in a life-affirming way. But when we feel this demand in the light of our great history, our grief is transformed into an invigorating force. For the life that is demanded of us is not a renunciation in favour of the Other – but a turning towards our very own destiny and thus a celebration, in new rituals before new altars.

6

This is how we feel about our origin, our community, our task. ‘Man is a space, an opening through which the universe celebrates its existence.’ Bach can provide us with the hymns for this. But it is up to us to celebrate the festival. – How dark the eagle owl calls out of the north face on midsummer’s night! How proudly the fire lily stands at the back of the valley under the tall larches. – At the beginning of this year, we want to kneel before a robin and greet the old maple. We want to feel the rain on our faces. We want to remember plankton, the origin of photosynthesis, gravity. And if we really do that, we will gradually start to live completely differently. We will open our eyes to our fall. We will stand in the alleys of our cities, shuddering, feeling the great pain of our devastation. We will plant a large garden, free the calves, dance around bright fires with our children.