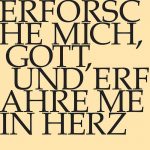

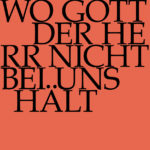

Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält

BWV 178 // For the Eight Sunday after Trinity

(Where God the Lord stands with us not) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Hilf, Herr! Die Heiligen haben abgenommen, und der Gläubigen ist wenig unter den Menschenkindern. – «Weil denn die Elenden verstört werden und die Armen seufzen, will ich auf», spricht der Herr, «ich will eine Hilfe schaffen dem, der sich darnach sehnt.» Die Rede des Herrn ist lauter wie durchläutert Silber im irdenen Tiegel, bewähret siebenmal.

So sind wir nun, liebe Brüder, Schuldner nicht dem Fleisch, dass wir nach dem Fleisch leben. Denn wo ihr nach dem Fleisch lebet, so werdet ihr sterben müssen; wo ihr aber durch den Geist des Fleisches Geschäfte tötet, so werdet ihr leben. Denn welche der Geist Gottes treibt, die sind Gottes Kinder. Denn ihr habt nicht einen knechtischen Geist empfangen, dass ihr euch abermals fürchten müsstet; sondern ihr habt einen kindlichen Geist empfangen, durch welchen wir rufen: Abba, lieber Vater! Derselbe Geist gibt Zeugnis unserm Geist, dass wir Gottes Kinder sind. Sind wir denn Kinder, so sind wir auch Erben, nämlich Gottes Erben und Miterben Christi, so wir anders mitleiden, auf dass wir auch mit zur Herrlichkeit erhoben werden.

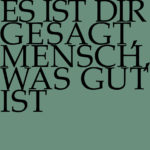

Sehet euch vor vor den falschen Propheten, die in Schafskleidern zu euch kommen, inwendig aber sind sie reissende Wölfe. An ihren Früchten sollt ihr sie erkennen. Kann man auch Trauben lesen von den Dornen oder Feigen von den Disteln? Also ein jeglicher guter Baum bringt gute Früchte; aber ein fauler Baum bringt arge Früchte. Ein guter Baum kann nicht arge Früchte bringen, und ein fauler Baum kann nicht gute Früchte bringen. Ein jeglicher Baum, der nicht gute Früchte bringt, wird abgehauen und ins Feuer geworfen. Darum an ihren Früchten sollt ihr sie erkennen. Es werden nicht alle, die zu mir sagen: «Herr, Herr!», in das Himmelreich kommen, sondern die den Willen tun meines Vaters im Himmel. Es werden viele zu mir sagen an jenem Tage: «Herr, Herr! Haben wir nicht in deinem Namen geweissagt, haben wir nicht in deinem Namen Teufel ausgetrieben, haben wir nicht in deinem Namen viele Taten getan?» Dann werde ich ihnen bekennen: Ich habe euch noch nie erkannt; weichet also von mir, ihr Übeltäter!

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Simone Schwark, Stephanie Pfeffer, Susanne Seitter, Mirjam Wernli, Baiba Urka

Alto

Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Lisa Weiss, Laura Binggeli, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Walter Siegel, Joël Morand, Manuel Gerber

Bass

Tobias Wicky, Christian Kotsis, Daniel Pérez, William Wood, Serafin Heusser

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler, Monika Baer, Aliza Vicente, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa Encinas

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Corno

Thomas Friedländer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Thomas Hürlimann

Recording & editing

Recording date

18/08/2023

Recording location

Speicher AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Composer of interlude to chorale no. 7 “Die Feind sind all in deiner Hand”

Thomas Leininger

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

30 July 1724, Leipzig

Text sources

Justus Jonas (movements 1, 4, 7 based on psalm 124); unknown (movements 2, 3, 5, 6)

In-depth analysis

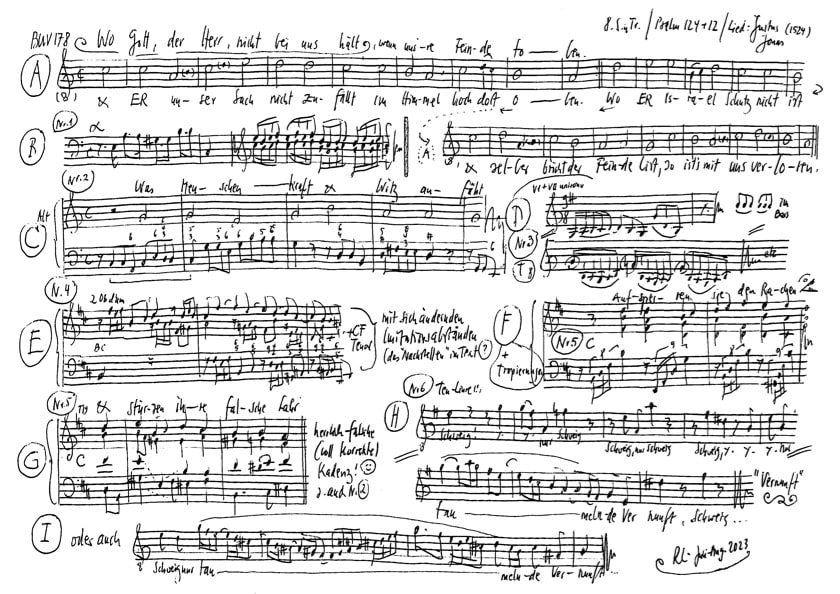

Inspired by the chorales for their respective Sunday or high feast day, the works in Bach’s second annual cantata cycle are fascinating in that they demonstrate an astonishing variety from week to week despite having the same basic approach. In the chorale cantata BWV 178 “Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält” (Where God the Lord stands with us not), composed in 1724 for the Eighth Sunday after Trinity, almost all the movements draw on the hymn (a rhyming version of Psalm 124 that Justus Jonas, a trusted colleague of Martin Luther, had written already in 1524), thus lending it the character of a chorale partita.

Scored for four-part choir, strings, two oboes, horn and continuo, the introductory chorus rivets listeners through its application of dramatic affect, rendering the vocal lines about strength under duress as an ominous natural spectacle. Terse, dotted rhythms and rapid circling figures evoke a sense of constant danger that is valiantly countered by the choir in long notes ere the erratic, staggered entries of the lower voices illustrate the furious “Toben” (raging) of Christ’s enemies. Here, Bach’s versatile treatment of the choir voices and pre-imitations displays great interpretive mastery that extends to images of bewildered, anxious stammering and raises the chorale chorus – charged with dark earnestness by the accompanying horn part – to a highlight in the cantata cycle.

The alto recitative continues this exploration of the chorale on two levels: the recitative insertions commenting on the chorale text are sung a tempo while the opening continuo phrase presents the first hymn line in quaver diminution – an effective motif that Bach repeats with piercing intensity at varying pitch levels. It is only against the backdrop of this relentless accompaniment, circling aimlessly in analogy to ungodly human activity, that the soloist’s calmly declaimed words of solace enable a measure of how much freedom is to be gained through the guidance of the Highest. Indeed, his mighty hand could hardly be better illustrated than by the tight structure of this setting.

With a gestural force reminiscent of Antonio Vivaldi’s Sea Storm concerti, the following aria employs the image of “wilde Meereswellen” (savage ocean waters) to depict the enemies attacking Christ’s church. No doubt the arrestingly realistic combination of even threenote figures in the continuo and swirling maelstroms in the unison violins was inspired by Bach’s own experience of the North German sea. Amid this musical tempest – at times openly raging, at times ominously deep – the bass soloist has to muster all his strength to keep his rolling “Schifflein” (little ship) on course.

The tenor recitative “Sie stellen uns wie Ketzern nach” (They lie in wait like heretics) leads from the raging storm into the snares of dogmatic interpretations. Accompanied by a trio of two oboes and continuo with interrelated motifs, the vocal soloist reintroduces the familiar chorale. Whether listeners choose to interpret the intense discourse of the soloistic woodwinds as ranting persecutors or as the insistent expression of promised salvation will have as much to do with their individual character and emotional state as it does with the answer to who is being silenced by the rabid descending motif of the terse continuo part.

The following approach to a Choral et Recitativo a tempo giusto offers a genuine surprise as Bach draws ever-new aspects from the already thoroughly explored hymn. Over a continuo part of octave arpeggios at continually varying pitches, the litany-style block presentation of each chorale line in four parts is interspersed with dramatic solo recitative passages.

In the tenor aria, this valiant self-assertion undergoes a further, and, from a present-day perspective, disturbing escalation; indeed, the standoff expressed in the abrupt, alternating motifs is no longer pitted solely against the snarling adversaries in this early Reformation battle hymn but also against “taumelnde Vernunft” (giddy intellect). What we today appreciate as a tool of well-considered judgement is decried in both text and music as untenable, erratic hubris that is best overcome by the Lutheran theology of the cross and the hope of redemption, as proffered by the tenor. It is then Bach’s musical interpretation following the pared down scoring and unadorned clarity of the middle section that delivers the longawaited solace – a potent turning point that, incidentally, should give pause to the notion favoured by many a scholar that Bach identified wholesale with the ideas of the Enlightenment.

After the many artful, chorale-based transformations, the two verses of the closing chorale hark back to the powerful essence of the hymn. Listeners may well question whether every member of Bach’s cosmopolitan Leipzig congregation agreed wholeheartedly with the chorale’s cosmologically underpinned rejection of the world, as does the industrious keyboard commentary on this recording.

Libretto

1. Chor

Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält,

wenn unsre Feinde toben,

und er unser Sach nicht zufällt

im Himmel hoch dort oben,

wo er Israel Schutz nicht ist

und selber bricht der Feinde List,

so ist‘s mit uns verloren.

2. Choral und Rezitativ — Alt

Was Menschenkraft und -witz anfäht,

soll uns billig nicht schrecken;

denn Gott der Höchste steht uns bei

und machet uns von ihren Stricken frei.

Er sitzet an der höchsten Stätt,

er wird ihrn Rat aufdecken.

Die Gott im Glauben fest umfassen,

will er niemals versäumen noch verlassen;

er stürzet der Verkehrten Rat

und hindert ihre böse Tat.

Wenn sie’s aufs klügste greifen an,

auf Schlangenlist und falsche Ränke sinnen,

der Bosheit Endzweck zu gewinnen;

so geht doch Gott ein ander Bahn:

er führt die Seinigen mit starker Hand

durchs Kreuzesmeer in das gelobte Land,

da wird er alles Unglück wenden.

Es steht in seinen Händen.

3. Arie — Bass

Gleichwie die wilden Meereswellen

mit Ungestüm ein Schiff zerschellen,

so raset auch der Feinde Wut

und raubt das beste Seelengut.

Sie wollen Satans Reich erweitern,

und Christi Schifflein soll zerscheitern.

4. Choral – Tenor

Sie stellen uns wie Ketzern nach,

nach unserm Blut sie trachten;

noch rühmen sie sich Christen auch,

die Gott allein groß achten.

Ach Gott, der teure Name dein

muß ihrer Schalkheit Deckel sein,

du wirst einmal aufwachen.

5. Choral und Rezitativ — Alt, Tenor, Bass

Auf sperren sie den Rachen weit,

Bass

nach Löwenart mit brüllendem Getöne;

sie fletschen ihre Mörderzähne

und wollen uns verschlingen.

Tenor

Jedoch,

Lob und Dank sei Gott allezeit;

Tenor

der Held aus Juda schützt uns noch,

es wird ihn’ nicht gelingen.

Alt

Sie werden wie die Spreu vergehn,

wenn seine Gläubigen wie grüne Bäume stehn.

Er wird ihrn Strick zerreißen gar

und stürzen ihre falsche Lahr.

Bass

Gott wird die törichten Propheten

mit Feuer seines Zornes töten,

und ihre Ketzerei verstören.

Sie werdens Gott nicht wehren.

6. Arie — Tenor

Schweig, schweig nur, taumelnde Vernunft!

Sprich nicht: Die Frommen sind verlorn,

das Kreuz hat sie nur neu geborn.

Denn denen, die auf Jesum hoffen,

steht stets die Tür der Gnaden offen;

und wenn sie Kreuz und Trübsal drückt,

so werden sie mit Trost erquickt.

7. Choral

1.

Die Feind sind all in deiner Hand,

darzu all ihr Gedanken;

ihr Anschläg sind dir, Herr, bekannt,

hilf nur, daß wir nicht wanken.

Vernunft wider den Glauben ficht,

aufs Künftge will sie trauen nicht,

da du wirst selber trösten.

2.

Den Himmel und auch die Erden

hast du, Herr Gott, gegründet;

dein Licht laß uns helle werden,

das Herz uns werd entzündet

in rechter Lieb des Glaubens dein,

bis an das End beständig sein.

Die Welt laß immer murren.

Thomas Hürlimann

I have gladly come to you, ladies and gentlemen – not only because the musical event shines beyond all borders, I have another reason. Appenzell belongs to my childhood country, which I wandered through hill and dale with my uncle in the years before elementary school. We wore the same clothes. On the head, as sun protection, a napkin lined at the corners, knickerbockers, nail shoes, backpack, walking stick. My stick had been shortened by my uncle to half its length; in his face smoked a Rössli stump, in mine burst from time to time the red bubble of a bazooka gum. So we went from “Säntisblick” to “Säntisblick”, my uncle would take a drink every time, and often his passion for introducing me to the secrets of mathematics took on threatening forms in the course of the long day’s hike. At that time, I taught myself to read by means of an illustrated Robinson book and with the gentle help of my grandmother; I was enthusiastic about adventurous sea voyages and had no use for the “sacred clarity of mathematics,” as my uncle invoked it with glazed eyes.

One afternoon it was a matter of probability theory. According to their laws, claimed the uncle, we would meet here, on the country road to Gontenbad, only in the “most unlikely case” an automobile with a Zug license plate. My pride in my homeland hurt, I shouted indignantly, “That’s not true!”

At first, the uncle got angry, but then he said confidently: “You can rely on mathematics. If a Zug car really does come by, you’ll get a nickel.”

After anxious minutes of waiting, a column of three distinguished convertibles crept up, all with sporty costumed crews, whitewall tires, and the foremost car with a clearly visible license plate: ZG, Zug, the blue-and-white crest. Before the uncle had recovered from his fright, the second car passed: ZG, train, the blue-white crest, just behind it car number three: ZG, train, the blue-white crest, and believe me, more important than the fortune won was the experience of the player, who was plunged into pure happiness by his hit.

*

Many years later, I had failed in my studies, I had lost everything playing poker in a gloomy pub at the Stuttgart train station. Hungry, thirsty, desperate, I threw myself on the mattress in the shabby boarding house where I had rented a room but not yet paid for it, took the dusty Bible from the nightstand, opened it above me – and down fluttered a whole bundle of beautiful green dollar bills. I suppressed the impulse to report my find, as well as the temptation to return to the poker game. Instead, I got myself some beer and cigarettes and immersed myself in the Old Testament, in the books of the prophets. Just as a gambler bets on luck, I told myself, the prophet bets on misfortune. So there had to be some kind of relationship, and since Isaiah, Amos and Habakkuk had an amazing hit rate, there was certainly something to learn from them. Now I was not so naive to seriously believe that by studying the Bible I would become a super gambler who knows in advance on which number the roulette ball would click. If this were possible, the casinos would probably be teeming with rabbis and pastors who were constantly breaking the bank. No, it didn’t work out that way. But what gave a simple shepherd like Jeremiah the vision to see beyond the edge of the present? What was his secret, his trick?

One afternoon he was grazing his flock under a piercing sun. Grumpy mood of dogs and sheep. The ground was sandy, only a few thorny bushes on which they nibbled their muzzles bloody. That the Lord was above them was beyond doubt, after all they were in His creation, but could it be, Jeremiah asked himself, that the Lord was asleep? And behold, the moment he thought this thought, a juniper branch showed itself to him. Thus was revealed to Jeremiah: God is awake.

*

Gambling, as every gambler knows, is unreasonable. As unreasonable as my assertion that a Zug automobile would appear on the road to Gontenbad, as unreasonable as the prophet’s saying that it would soon rain sulfur on Sodom. “What is, is reasonable”, Hegel holds against it, and all functionaries of this world might share his view. The unreasonable prophet and the unreasonable gambler, however, adhere to the cantata text you just heard: “Silence, silence, reeling reason! Speak not.”

Reason, Kant expresses it most clearly, covers only that part of reality which it has created itself. This applies to large parts of our thinking, including that of the planet, and in the field of natural science, where calculation, measurement, analysis, dissection are involved, the method is appropriate. “Man’s true being,” says Hegel, “is his deed.” Tat-logic, reason-determined. The juniper branch alone would never be recognized in this way. It is a beckoning coming from other dimensions. Aletheia, truth, Heidegger defines as that which “unbirches.” What reveals itself to us. As a doer, one has no chance there. In the grasping hand the branch would wither; it is a manifestation of the absolute, it blossoms in the wondering eye. The gambler experiences something similar when he bets against every mathematical probability and gets a full load from Fortuna’s cornucopia. Then the true being of man is not activity, but amazement. To accept. Accepting. Sinking humbly and gratefully to one’s knees when the blessing of money descends from the opened Bible. Or when the third convertible with the license plate ZG, Zug, blue-white coat of arms, purrs past. Reason has nothing more to say. It staggers off into the ditch, stunned.

*

Soon after Stuttgart, I freed myself from my passion for plays by outsourcing it to the stage. For years I occupied myself with Nestroy, in whom the fairy godmother represents the highest dramaturgical principle, but I never succeeded in transferring his tricks from Biedermeier to our thoroughly rationalized times. I was also unsuccessful when I let epiphanic moments flow into prose texts. Most of the time they fell victim to censorship in the final version, the censorship of my reason.

So I am aware that it is almost impossible to penetrate with words into areas which have not been colonized by reason. Sure, in the dreams this happens every night, but evenly, there formations appear to us which burst in the awakening like my bubble gum bubble at that time. Nevertheless, I would like to take the risk, because the mysterious door, which the cantata author and Bach evoke at the end of the tenor aria, is familiar to me – not from music, from the hospital.

It was the night before a life-defining operation. I was lying in sweaty pillows, hooked up to tubes, staring spellbound into the darkness. There, through the wide door, they would roll me out tomorrow and take me down in the goods lift, into the operating room. Last exit? A journey of no return? My fingers were clawed into the sheet, my heart was pounding up to my throat – and strangely, all of a sudden I became calm. How it happened, I don’t know, I can only say that it happened. It. It happened. It happened. The sickroom was suddenly the hall of a museum, and the only picture depicted a door in perfect beauty. It was the door I had just been staring at, but it no longer enclosed me in the confines of my fear, but opened up an unknown space. I was overcome by happiness, as I had been on the road to Gontenbad. Or like in the Stuttgart boarding house room when the blessing of dollars fell on me. I was now all gambler and all prophet, knowing: You have won, one way or the other. Either you will return to this room after the operation and a few days in intensive care, or behind the door of doors the timeless will receive you.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).