Nun danket alle Gott

BWV 192 // For Reformation Sunday

(Now thank ye all our God) for Reformation Sunday, for soprano and bass, vocal ensemble, strings, transverse flute I+II, oboe I+II and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Jessica Jans, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Anna Walker, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Tobias Knaus, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Alexandra Rawohl, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Manuel Gerber, Raphael Höhn, Sören Richter

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Grégoire May, Retus Pfister, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Elisabeth Kohler, Olivia Schenkel, Aliza Vicente, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama Herzig, Rebekka Brunner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa Encinas

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter, Thomas Leininger

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Abt Urban Federer

Recording & editing

Recording date

23/04/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Composer of bourée anglaise & gigue (introductory workshop)

Thomas Leininger

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

4 June 1730 – Sangerhausen palace church

Text

Martin Rinckart

In-depth analysis

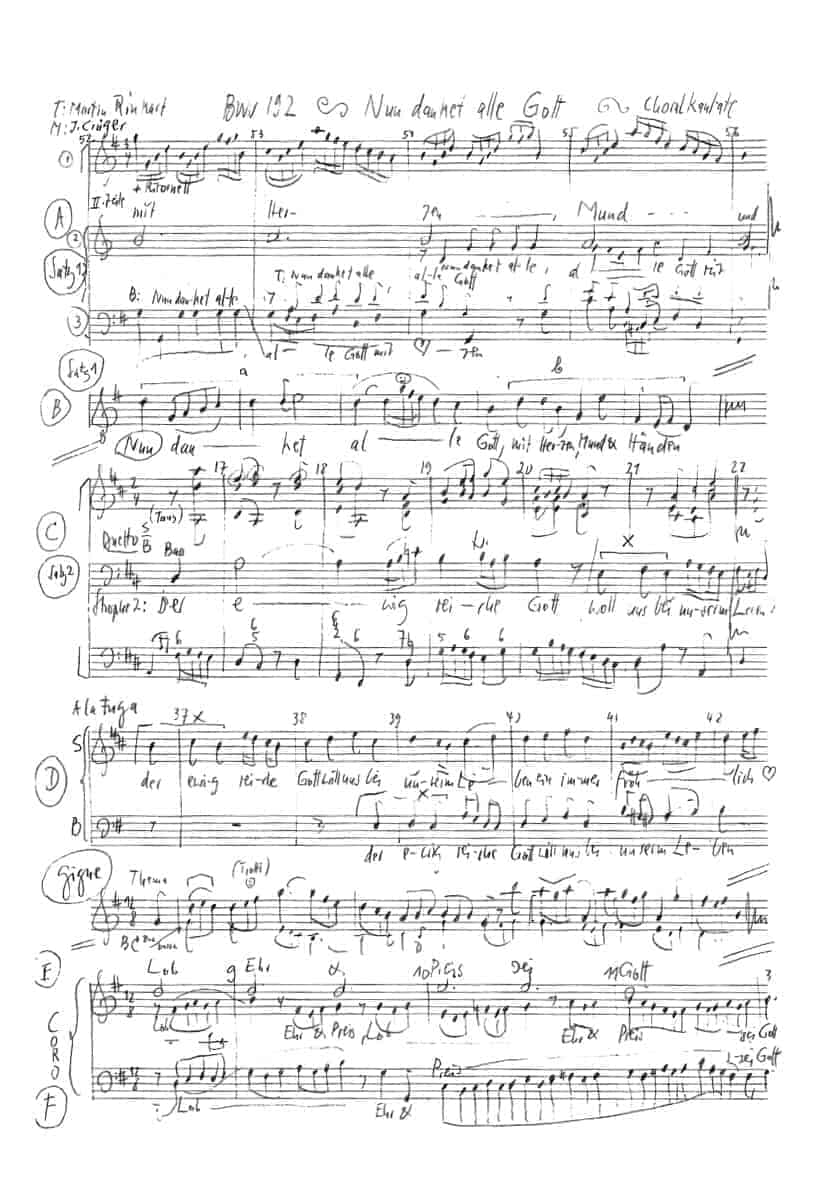

Like cantata BWV 184, BWV 192 also bears characteristics of courtly music style. Composed in 1730, it is one of Bach’s later sacred works and belongs to a group of four chorale cantatas per omnes versus – cantatas based on a straight hymn text with no alterations or additions by a contemporary librettist. While the exact occasion for the composition is unknown, the idea that it may have been commissioned by the Weissenfels court, with which Bach had long been connected and from which he had received the title of Kapellmeister in 1729, is in no way contradicted by the work’s elegant style and dance-inspired forms.

Set with four woodwinds, a lively, airy tone pervades the opening orchestral ritornello; when the vocal parts enter, they become part of this joyous momentum despite the gravitas of their opening motet-style phrase. While Bach assigns the Cantus firmus as usual to the soprano voice, he also integrates it into the choral aria, with its instrumental interludes and tutti figures, and transforms the typical pre-imitations of the lower voices into a confident, continuous part-chorus, thus creating an inspired concerto grosso that allows the setting to emerge as an ingenious innovation in the chorale cantata form – a development that no doubt also reflects Bach’s response to changing audience expectations. Because the original tenor part is lost, performance of the work is dependent on reconstructions; in this recording, we have chosen Detlev Schulten’s newer reconstruction rather than the version in the New Bach Edition contributed by Alfred Dürr.

Opening in equally vibrant style, the following aria for soprano and bass does not initially call to mind a chorale arrangement. Here, Bach juxtaposes jaunty orchestral figures with broad vocal phrases to attain – even by Bach’s standards – a particularly successful mix of rhythmic concision and hymnic cantabile. That the listener regrets the relative brevity of this structurally coherent movement is also not an effect to be taken for granted in the master’s music.

With its gigue-like style, the beginning of the closing chorus is akin to the finale of an orchestral suite; indeed, as the original score is lost and only the performing parts have survived, the possibility that the movement derives from an instrumental work cannot be ruled out. In this setting, the soprano projects soaring, long-note phrases of thanks while the lower vocal parts positively seem to dance: just as this cantata shows that high praise of God can also have an infectiously joyous side, it equally proves that Bach’s reverence for the Lutheran chorale did not exclude a bold and creative approach.

Libretto

1. Chor

Versus 1

Nun danket alle Gott

mit Herzen, Mund und Händen, der große Dinge tut

an uns und allen Enden,

der uns von Mutterleib

und Kindesbeinen an

unzählig viel zugut

und noch jetzund getan.

2. Arie — Sopran, Bass

Versus 2

Der ewig reiche Gott

woll uns bei unserm Leben

ein immer fröhlich Herz

und edlen Frieden geben

und uns in seiner Gnad

erhalten fort und fort

und uns aus aller Not

erlösen hier und dort.

3. Chor

Versus 3

Lob, Ehr und Preis sei Gott,

dem Vater und dem Sohne

und dem, der beiden gleich

im hohen Himmelsthrone,

dem dreieinigen Gott,

als der ursprünglich war

und ist und bleiben wird

Abbot Urban Federer

Cantata BWV 192 “Now thank ye all our God” – a formation of the heart

Ladies and gentlemen, I must confess: When I was invited to present my thoughts on Cantata 192 by Johann Sebastian Bach, there was a disappointment: 192? I don’t even know that one. And when, after a first glance at the internet, it is less clear than after reading today’s programme what this cantata was actually written for, and I also read that this cantata has not survived in its entirety, this increases my question mark: What should I say about this cantata? My answer is quite sober: nothing beyond the music and text! This cantata throws me – and thus also you – back to what is available. In the cathedral of St. Gallen, I would mark out the surroundings of this baroque music, which had already been written for 25 years when the cathedral of St. Gallen was built. In this Olma Hall, I am left in all sobriety with one of Bach’s shortest cantatas.

So I seek an entry point for my thoughts via my experience. And here two problems arise for me: It is true that the chorale cantata sets to music in three movements the three verses of the famous hymn “Now thank ye all our God”. But for me, this song in particular – together with other chorales – has been “sung to death” too often. What do I mean by this not very nice expression? Forget the fresh music-making of earlier. Imagine a church service on a Sunday morning, attended by people who have not yet fully emerged from the rumpled state of sleep and whose 20th birthday was a few years ago. Now the organ starts the chorale: The use of the voices is already sticky, the song doesn’t get off the ground right from the start and the first rise of the melody is slightly below the organ tone. At such a moment, I have only one thought: “Not this song again! How many verses does it have? Only three? Okay, that works…” This is no way to sing a praise of God that uplifts people and brings us real joy. When singing like this, I understand younger people, for example, who find this kind of song boring and would like better music in church. And the content doesn’t help either, to name my second problem. Can I today, with a view to our world, simply start with the words “Now thank ye all our God”, of whom it is then also said that he has “done us countless too good […] from the womb to this day”? How serious are we about this thanksgiving in view of the flood of refugees, the increasing poverty even in our latitudes, the pandemic, the never-ending wars and the threatening environmental issues?

Bach would not be Bach if music did not first come to my aid in my questions. The first chorale movement begins in a lively three-four time. Music and words seem sublime and playful at the same time, until the actual chorale melody begins. The second movement is dance-like and the third movement, as a final praise to God, is also dance-like. It is therefore difficult to sing this chorale to death. Rather, we would have to stand up in the first movement and lightly dance the chorale from the aria onwards. This cantata therefore aims at our attitude, if not outwardly, then certainly inwardly. This sung thanksgiving wants to lift us all up, to uplift man! And in the relationship between music and word, Bach also provides me with answers to my second problem: how to deal with this all too self-evident thanksgiving. When the chorus solemnly begins to give thanks to God, an almost jocular play with the words “with heart, mouth and hands” begins even before the cantus firmus. It is as if the cantata wants to hammer home at this point that we should stand as whole people and give thanks. This reminds me of my religious rule, in which St. Benedict wrote in the 6th century: “When singing the psalms, let us stand in such a way that our mind and heart are in harmony with our voice” (RB 19, 7). Those who pray and sing prayerfully do not do so in alienation from the world, from the body, from our thoughts. He who sings thanks opens his own heart and enters into a relationship. That is why St Benedict has us monks and nuns sing first thing every morning with Psalm 95: “Today, when you hear his voice, do not harden your hearts!” (RB pr 10).

Whoever opens her or his heart to God, so a first statement of this cantata, can give thanks without excluding the problems of the world. Bach shows that he wants thanks in any case at the end of this movement, where the choir begins to give thanks once more, although the verse has already been sung, only to end up surprisingly quickly in the final sound. Obviously, not only the finished person can give thanks. On the contrary, those who already have everything find it difficult to be grateful. Are we grateful people when we are happy? Or are we not much happier when we can be grateful? The relationship with God, with the One who transcends us, enables us to be grateful. The monk should cry out “Thanks be to God!” when a poor person or a guest knocks at the doors of the monastery (cf. RB 66, 3). He should do this in the awareness that the people of Israel were only guests in Egypt and thus experienced what it means to be a stranger and an outcast. And the monk should give thanks because in Christ’s suffering the door to God was opened to us completely. Gratitude is therefore a basic Christian attitude that does not exclude suffering, but allows us to persevere precisely in our problems. Otherwise, the cross would not be at the centre of Christianity.

There is also a play between words and music in the aria of the second stanza. In a dance-like duet between soprano and bass, the words “peace” and “joyful” enter into dialogue with each other, as if peace and a joyful heart produce each other. For the Rule of Bene-dict, it is clear that peace, for example, is not to be had easily, but to be striven for, even fought for. Thus it demands: “Seek peace and pursue it!” (RB pr 17, after Ps 34:15). And St Benedict speaks of joy most of all in the chapter on the fast. Obviously, expectation can lead to more joy. Man should not lose the elasticity of the soul. The Rule says: “Expect the holy feast of Easter in the joy and longing of the spirit” (RB 49, 7). In this direct comparison of the cantata with the Rule of Benedict, not only thanksgiving, but also joy and peace are not merely a matter of feeling, but an attitude of the heart that does not make us bitter, but allows us to grow in longing.

If I understand Cantata 192 here as a formation of the heart that leads us to thanksgiving, peace and joy, I find this concern also reflected in the biblical book of Jesus Sirach, whose text is the basis for the song “Now thank ye all our God”. After the words that our cantata sets to music – thanksgiving to God and the wish that God give us gladness of heart and peace – Jesus Sirach goes on to say: “Blessed is he who dwells on these things and takes them to heart and becomes wise. For if he does this, he has strength for everything, because the light of the Lord is his track” (Sir 50:28 f.). The text itself, on which Martin Rinckart bases himself, thus aims at the formation of the heart. It is therefore only logical for me that Bach’s music also wants to fill our hearts with gratitude, joy and peace. Praise to God should uplift and uplift people, when singing, playing and listening!

So I don’t have to be in a perfect mood and situation when the first bars of the chorale “Now thank ye all our God” sound. The actual foundation of thanksgiving is not found in feelings and optimal conditions, but in what the Benedictine Rule calls the “expectation of Easter in longing and joy”. In the cantata, this idea is found again for me in the duet between soprano and bass. As between joy and peace, there is also a dance-like play in the aria between the expressions “out of all distress” and “redeem”. In the redemptive Easter, our longing finds its goal and rest! According to this music, gratitude, joy and peace have a basis where man faces his needs and fears and believes that there is an Easter, or if you like it differently: that there is a goal of our longing, especially in all our needs.

Since out of the relationship with the living God our heart can be filled with thanksgiving, joy, peace and hope in every situation, the lilting praise of God bubbles forth dance-like in the last movement of the cantata. Out of this formation of the heart, Jesus Sirach can also exclaim in gratitude, following the words I quoted earlier: “Blessed is the Lord for ever and ever! Amen, amen!” (Sir 50:29). For St Benedict, too, the relationship with the living God aims at a joyful heart: “But whoever continues in the monastic life, his heart becomes wide, and he walks the path of God’s commandments in unspeakable happiness of love.” For Martin Rinckart, the heart also becomes wide in the relationship with God, “as it was in the beginning / and is and will remain / so now and forever”. And us? We too can join in this series of the formation of the heart through the praise of God. For us, it is Bach’s music that uplifts us and gives us joy. Therefore, dear listener, but also esteemed musicians, let us play, sing and listen to the cantata again with an open heart, so that it also says for us: “Today, when you hear his voice, do not harden your hearts. Rather, seek peace and pursue it”.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).