Der Herr denket an uns

BWV 196 // For a wedding

(The Lord careth for us) for soprano, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Cornelia Fahrion, Noëmi Sohn Nad

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Sören Richter

Bass

Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Guisella Massa

Bassoon

Carles Cristóbal

Lute

Niels Pfeffer

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Michael Maul

Recording & editing

Recording date

17/03/2023

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

1707–1708 (possibly Arnstadt or Dornheim)

Text based on

Psalm 115:12–15

In-depth analysis

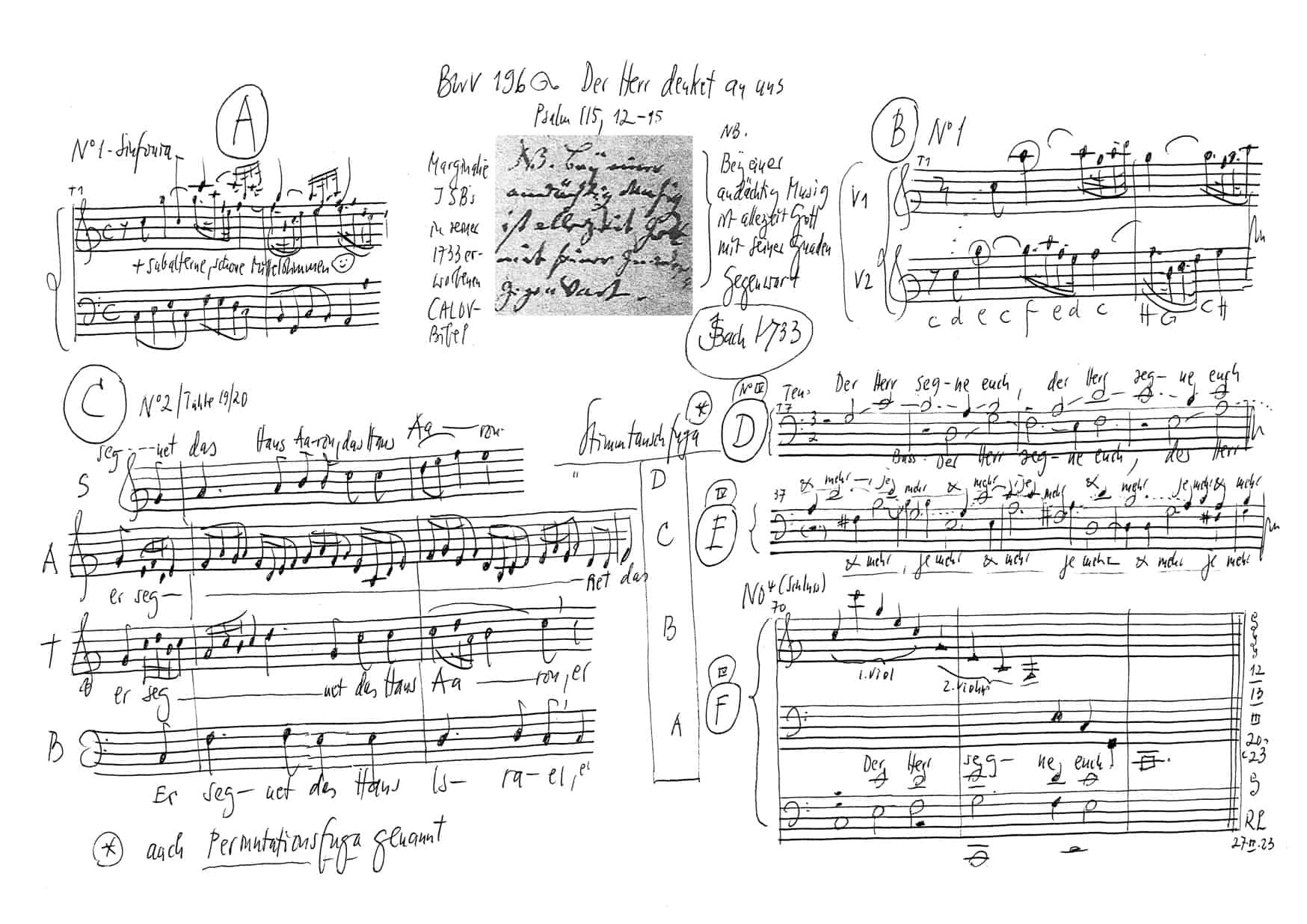

The score of BWV 196, one of Bach’s earliest cantatas, survives today only as a copy made by one of his students, making it impossible to determine which couple Bach was honouring with this wedding music. Although it is tempting to imagine that Bach composed the work for his own wedding to his cousin Maria Barbara, which took place on 17 October 1707 in Dornheim near Arnstadt, it could equally have been for the wedding of the Dornheim parson, Johann Lorenz Stauber, to a member of Bach’s extended family in June 1708.

Stylistically, the work represents a certain transitional period, as it exhibits individual movements but no recitatives and only tentative use of operatic da-capo-aria form; as such, it was likely composed in the first decade of the 18th century and not in connection with the official seat of a sovereign. Furthermore, instead of setting newly composed paraphrases of biblical texts, a practice already common among other composers, BWV 196 uses only words from the scriptures, verses 12 to 15 of Psalm 115, to realise a touching musical panorama of blessings that are of relevance for the individual, the family and the community.

The introductory sinfonia, a compact setting with a running bass, establishes a lively yet delicate tone, interweaving spirited ascending gestures and dotted figures à la Corelli. Given the dialogue-like nature of the movement, the listener may well ask whether the alternating harmonic tension and lightfooted resolution typical of this style projects an optimistic view of the bridal couple’s married future. Either way, the ensuing tutti movement echoes this gesture, and its two-part form of a loosely gestural prelude (“Der Herr denket an uns” – The Lord careth for us) and a didactic fugue (“Er segnet das Haus Israel” – He blesseth the house Israel), is distinctly informed by Bach’s experience as an organist. This is seen in the treatment of the strings, which are used to reinforce selected figures and successively increase the number of voices.

The A-minor soprano aria “Er segnet, die den Herren fürchten” (He blesseth those the Lord fearing) strikes an introspective tone. Over a lilting continuo, the voice and obbligato violin unite in a delicate and poignant duo, leaving the listener reluctant to let this 34-bar gem draw to a close; here, the contrasts in melody and pitch on the words “klein” (small) and “gross” (large) demonstrate not only Bach’s sure compositional eye but also his musical wit. The ensuing tenor and bass duet, shaped by block-style use of the strings, combines an ascending fourth leap on the words of blessing with flowing figures and is unafraid of indulging in dulcet consonances.

Following these gentle settings, the church once again resounds with energy and holy proclamations in the closing tutti movement. Driven by diverging semiquaver runs in the strings, the four vocal parts declaim the joyous text of the Psalm, alternating between block and staggered entries, ere an extended double-fugue setting on the word “Amen” again showcases the artistry of the wellwishing composer – who was perhaps the bridegroom himself.

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Chor

«Der Herr denket an uns und segnet uns. Er segnet das Haus Israel, er segnet das Haus Aaron.»

3. Arie — Sopran

«Er segnet, die den Herrn fürchten, beide, Kleine und Große.»

4. Arie — Duett: Tenor und Bass

«Der Herr segne euch je mehr und mehr, euch und eure Kinder. Der Herr segne euch.»

5. Chor

«Ihr seid die Gesegneten des Herrn, der Himmel und Erde gemacht hat; ihr seid die Gesegneten des Herrn. Amen.»

Michael Maul

Esteemed, artful, even dearly beloved Johann Sebastian Bach!

Allow me to write you a letter today, knowing full well that you will unfortunately not answer me – well, at least not in this life. Perhaps you would have no interest at all in even entering into an exchange with me – a scribbler limited to his words, who now and then sets himself up as an exegete of your works and an explainer of your life. For as your son Carl Philipp Emanuel already admonished your first biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel: “one has many abentheuerliche traditions of my father. Few of them may be true and belong to his youthful fencing pranks. The Blessed One never wanted to know anything about it; so leave these comical things [simply] out.”

But, dear Bach, if it may have been the case that you and your family wanted to be judged solely by your compositions, I must counter you with one thing: With your more than one thousand fantastic compositions on the one hand and the “oyster-like secrecy” so aptly attributed to you by your colleague Paul Hindemith on the other, you have done just about everything to ensure that we, the astonished posterity, constantly ask questions about when?, where?, how?, who? and why? And exactly for this reason I have to write you a letter today, because I simply want to get rid of my questions.

However, if I were to list all the questions I have for you now, this letter would become a novel. The piece that has just been played – an immensely fresh-sounding wedding cantata, composed at the very beginning of your career as a vocal composer, perhaps even written for your own wedding on October 17, 1708 – well, this piece prompts me to focus my questions on the genesis of your mastery. For one thing in particular drives me to wonder about your complete works: Even your earliest surviving vocal works – they all seem to date from the one year that you spent as organist in Mulhouse from July 1707 to June 1708 – all of these earliest cantatas are incredibly mature-looking compositions, indeed most are simply accomplished masterpieces. Let us think, for example, of your incredible “Actus tragicus” BWV 106, that epochal compositional examination of dying and the path to paradise, about which Alfred Dürr rightly writes that it is a piece of world literature, with which you, phenomenal Bach, left all your contemporaries far behind at a stroke. Or let us think of your choral cantata “Christ lag in Todesbanden” BWV 4 or your psalm concerto “Aus der Tiefe” BWV 131, both of which you also put down on paper at some point in your 22nd year in Mühlhausen.

Yes, and therefore I ask myself full of curiosity and at the same time somewhat desperately, because I don’t have a proper answer: What was the decisive factor that you were able to catapult yourself literally “from the depths” of the Thuringian province to the top of Protestant church music within a year. Of course, and this impresses me most of all: without breaking with tradition in your compositions. Quite the opposite: unlike your friend Georg Philipp Telemann, who at that time set out to fundamentally reform church music with the new form of the cantata consisting of freely composed arias, choruses and recitatives, in your first attempts at sung musical praise of God, which are documented to us, you exclusively used familiar genres. Like your ancestors and models, you composed sacred concertos on the basis of biblical and choral texts – the cantata that we perform here in Trogen today is formally a thoroughly antiquated psalm concerto. But, incredible Bach, how you experimented with these traditional forms, how you playfully mixed seemingly contradictory elements, never as an end in itself, but always in the service of musical text exegesis, yes, that was simply without precedent. At the same time, most of your early vocal works frankly do not at any point convey the impression of a searching beginner, but rather of an experienced, detached composer who had been washed with all the waters, who would have done nothing else in his lifetime than compose vocal music “Soli Deo Gloria”.

So, dear Bach, please tell me, how was this possible for you?

Well, since you won’t answer me, I’ll have to go looking for myself, and I hope I’m not offending you.

When I look at the text of our cantata today – it comes from the 115th Psalm and is in essence a kind of alternating song of priest and congregation of the chosen Israelite people – well, when I look at this text, one word catches my eye quite centrally, the word: bless, or in the last verse “the blessed of the Lord”. In fact, the word “bless” appears at least once in each of the four verses, and each time, dear Bach, you found a new form, a new musical thought, to illustrate this blessing, that is, God’s attention (with the effect of sending out happiness, protection and good prosperity to the blessed), splendidly in notes. Most touchingly, I think, in the magnificent soprano aria – the first full-blown aria, as far as I can see, in your entire cantata work. Here you have indeed bestowed the most beautiful melismas and embellishments on the word bless. And in the following duet, which is still completely rooted in the form of the music of your ancestors, the text dealing with the miraculous increase of blessing for the chosen people has inspired you to literally make the constant growth of blessing sound by means of skilful reverberations and echo effects.

Therefore, hand on heart, dearest sound speaker Bach: The word blessed obviously inspired you very much – and I assume: not least because you knew that you yourself had also received many blessings in your life.

To express myself more clearly: I do not mean so much that the good Lord – we are still talking about a wedding cantata, possibly composed for your own marriage – blessed you with a fair wife – although your Maria Barbara was undoubtedly a wonderful blessing for you. I rather mean, on the other hand, that God gave you something in life which you yourself certainly considered a very special gift: namely, a unique musical talent, or as you would have said, “good musical profectus.” And this not only to you: Your son Carl Philipp Emanuel expresses it in a touching way at the very beginning of the obituary for you that he wrote four years after your death. I may quote: “Johann Sebastian Bach belongs to a family to which love and skill for music seem to have been given by nature, as it were as a general gift for all its members.

Yes, you, the Bach family of musicians, starting with the sons of Veit Bach, the master baker from Wechma, were – to remain in the image of our 115th Psalm – blessed with musical talent, and they and their children’s children made their profession out of it, and it seems that the more they lived, the more they made music, se more they composed, the more they were blessed.

Blessed Bach, of course, today we have the impression that you have received the greatest portion of musical talent from God’s blessing pot within your family. Perhaps you would agree. But I suspect you would also counter that, at the same time, the good Lord has placed an outsized portion of hard trials upon you, and this already at a young age. For you certainly had a good start, so as the youngest offspring, as the Benjamin in the family of the Eisenach town piper Ambrosius Bach. But the fact that in your tenth year the Lord robbed you of your father and mother within only nine months was really a hard blow of fate and will have pulled your feet out from under you. But it was already apparent at that time that you were attracted to making music on keys. Your son describes in the necrology, but most certainly based on your own narrative:

“Johann Sebastian was not yet ten years old when he saw himself deprived of his parents by death. He went to Ohrdruff to his oldest brother Johann Christoph, organist there, and under his guidance laid the foundation for playing the piano. The desire of our little Johann Sebastian for music was already immense at this tender age. In a short time, he had completely mastered all the pieces that his brother had freely given him to learn. However, a book full of piano pieces by the most famous masters of the time […], which his brother possessed, was denied him, despite all pleading, who knows for what reasons. So his eagerness to get further and further gave him the following innocent fraud. The book lay in a cupboard that was merely locked with barred doors. So he took it out – because he could reach through the lattice with his small hands and roll up the book, which was only stapled in cardboard, in the cupboard – in this way, at night, when iedermann was in bed, and wrote it down […] at moonlight. After six months, this musical booty was happily in his hands. He secretly sought to make use of it with great eagerness, when, to his greatest heartache, his brother became aware of it and took away his copy, which he had made with so much effort, without mercy. A miser who lost a ship on the way from Peru with a hundred thousand thalers may give us a vivid idea of our little Johann Sebastian’s grief over this loss. He did not get the book back until after his brother’s death.

Well, dear Bach, in the touching moonshine anecdote your son draws the picture of you as an extremely talented budding musician, who was carried by the “zeal to get further and further”, and who subordinated everything, really A-L-L-E-S, to the unconditional will to develop his talent. Yes, even the imposed prohibitions of your big brother – after all, your voluntary breadwinner and surrogate father – could not stop your zeal, your eagerness to get further and further musically.

Honestly, ambitious Bach, I believe that immediately, because when I think of the determination, not to say the doggedness, with which you then went to work from the age of 18 on your first organist position in Arnstadt; how you “confundiret” (i.e., confused) the congregation there with wacky chorale accompaniments. and how you then, after the Superintendent had reprimanded you for this, lapsed into the opposite and demonstratively played much too short preludes, you insulted liverwurst, because you probably felt chronically underappreciated; or how you bravely refused to perform even one note of figural music in church with the B-flat line-up of the local school choir because the result would have been below your standard; how you then, barely 20 years old, attacked a 22-year-old high school student with your sword when he courageously confronted you because you had previously called him a “zippel bassoonist”, i.e. a lousy amateur, at a rehearsal in front of the entire team: Well, from my point of view, all this paints the picture of a rather obsessed young keyboard virtuoso, carried through and through by the “zeal to always get ahead”.

And this fiery zeal by no means stopped the moment you landed your first job. As it so aptly continues in your obituary:

“Here in Arnstadt, a particularly strong urge he had to hear as much as he could from good organists led him to travel on foot to Lübeck to listen to the famous organist at St. Mary’s Church, Diedrich Buxtehuden. He stayed there, not without benefit, for almost a quarter of a year.”

Yes, that’s right, dear Bach: a quarter of a year – and you accepted the fact that you exceeded your submitted vacation of four weeks by a factor of three. The telling off that you were allowed to listen to afterwards by your Arnstadt superiors certainly left you quite cold, because I assume: you, the musically so blessed one, saw yourself on a more important mission and definitely called to higher things. The Philistines were allowed to rage!

But be that as it may. When you then – because your own aspirations and the expectations of your Arnstadt authorities simply did not want to fit together – moved to Mühlhausen as organist in the early summer of 1707, you suddenly discovered an interest in church music beyond the organ – and gave the Mühlhausen people (and us astonished posterity) a handful of dreamlike first cantatas. Soon after your arrival, your patron, the influential Mühlhausen mayor Conrad Meckbach, celebrated his 70th birthday – perhaps his birthday or his name day. You will remember it well, honored Bach, because you also joined in the celebrations: with your cantata “Nach Dir, Herr, verlanget mich” BWV 150. At that time, you did everything you could to make the mixture of verses from the 25th Psalm and freely poetized texts strikingly meaningful with your sheet music, in other words: to make the words sing – freely according to the guiding principle that Martin Luther already preached: “God’s word wants to be preached and sung.” Because: “He who sings prays twice!”

In the middle of this cantata is the fifth verse of the psalm: “Guide me in your truth and teach me, for you are the God who helps me; daily I wait for you.” And here, blessed Bach, you presented a clou that always impresses and especially moves me. For in the first eight measures you drew a musical picture for the words “Guide me in your truth” that could hardly have been more vivid. While you have the four singers invoke God’s assistance six times in succession with the block-like exclamation “Leite mich” (“Guide me”), a scale runs in parallel, beginning low down in the bass and alternating in time, through all the vocal and instrumental voices in a purposeful upward direction until it finally arrives in the first violin, which finally reaches the three-note d and thus symbolically the kingdom of heaven. Highest art packed comprehensibly for everyone, in short: a stroke of genius!

Dear Bach, I do not know whether I, as a scribbler limited to my words, express myself clearly and whether your composition is still present to you now that you are reading my lines. Therefore, allow your faithful disciples of St. Gallen to pre-music this passage once for both of us:

*****

Dear Bach, could it be that you have been somewhat proud of having traced here, as it were, the miniature of an entire life’s journey within only eight bars of music? And could it also be that while you were pondering the right musical image for this text, your own life to date was also passing you by? In any case, I find that these eight bars are truly emblematic of you, the fascinating, ambitious and tremendously determined young Bach. For indeed, your first 22 years of life had been full of fateful events and a series of hard tests of your trust in God. At the same time, you indulged in many an escapade because, borne by the “zeal to always get ahead,” you literally wanted to go through the wall with your head. But in the end, several “divine fates” and, of course, your own irrepressible diligence have led you straight up the career ladder – like the scale in the cantata BWV 150.

And then, determined Bach, when you had been organist in Mühlhausen for barely a year and had just convinced the aldermen to substantially expand your instrument, the organ of the Blasius Church, at great expense, you left for Weimar on short notice. Disappointment all around; and the reasoning for this decision also makes me sit up and take notice. You wrote to the aldermen of Mühlhausen that you had always tried to perform “a regulated church music in God’s honor” – i.e. vocal music in the church service – and that you had therefore “acquired a good apparatus of the most exquisite church pieces […] at no extra cost. But it simply did not want to happen that the sung church music actually became part of your responsibility. Now, however, God had unexpectedly “arranged” for you to be appointed as organist in the court chapel of the Duke of Saxony-Weimar. And this divine providence you wanted to face, as you write, “for the preservation of my final purpose because of the well-fitting church music” now absolutely.

Yes, dear Bach, again you felt blessed and followed your mission, your final purpose, that is, the meaning you saw in your life. And if I were now to remind you further of what happened during your years in Weimar, Köthen and ultimately Leipzig, I would go on and on raving about the constancy with which you, as a composer, set yourself ever new, ever more difficult tasks and, even under the greatest time stress, at the latest in Leipzig, put masterpieces down on paper with fiery zeal at weekly intervals, in fact “Soli Deo Gloria”, that is, in honor of God alone.

Yes, our amazement at your tireless creativity, which was coupled with a unique artistic craft and an incorruptibly high standard for yourself, is almost boundless. And yes, I must resignedly confess. You and your mastery remain inexplicable to us.

‘Oyster-like secretive’ Bach, but could it be that you at least once let slip how you yourself explained the genesis of your genius? Back then, in the late 1730s, when the music publicist Johann Adolph Scheibe severely criticized you in a letter to the editor because of your allegedly unsingable, “turgid”, “confused” and therefore “against nature” composed vocal works. At that time, you commission your confidant Johann Abraham Birnbaum twice to publicly contradict Scheibe. There are two passages in Birnbaum’s long defense writings where I have the impression that you are speaking to us yourself. There it says, referring to your uniquely complex compositional style:

“What I have been able to achieve through diligence and practice, another person who has only half the nature and skill must also be able to achieve. … Everything is possible if one only wants to and makes the greatest effort to transform one’s natural abilities into skilful skills through untiring diligence.

And elsewhere Birnbaum says, referring to the often immeasurable difficulties, according to Scheibe, with which you regularly confronted your singers:

“He [meaning you, dear Bach] always sets according to the nature of the singers. At times, however, he gives the instrumentalists and singers the opportunity to attack each other a little more than usual, in order to bring out something that they initially thought impossible because they did not try. … But experience has taught that the impossible becomes possible when diligence, skill, and practice have happily overcome all difficulties.”

Yes, dear Bach, I believe these words remain simply the only answer you have given us to the question of the genesis of your genius: Constant diligence, fiery zeal – that is how you constantly outgrew yourself; and that is also why it was possible for you to put on paper such incomparable works in your very first year as a composer of cantatas. Nevertheless, highly industrious Bach, your answer turns out to be rather unsatisfactory for us astonished posterity, who would like to explain everything rationally. And this brings me back to the starting point of my letter, to your cantata “Der Herr denkt an uns” (The Lord thinks of us) with this very special emphasis on the word Gesegnet (Blessed). Yes, dear Bach, I believe you that you have indeed explored and plumbed the stormy sea of counterpoint with immeasurable diligence throughout your life, perhaps even like no other; and that, especially in your young years, you spent whole nights absorbing everything of good music that you could grasp, and instead of enjoying life, day and night you thought doggedly and with relish about the possibilities of processing musical themes. But even this does not adequately explain the genesis of your genius, because others were also diligent and obsessed, and you don’t always succeed at everything, and certainly not well (I myself also practiced the violin for eight hours a day at times, and I consider it a great blessing that you never had to listen to that).

In the end, dear Bach, you Oberfleißiger were also a blessed man of the Lord – a blessed man who developed his extraordinary gift with manic zeal throughout his life – and who, carried by his, as you yourself say, “final purpose” of composing “well-regulated church music in God’s honor”, truly advanced to the status of a minstrel of God.

Divine Bach, you know what, it is actually perfectly alright that you leave all my questions ironically unanswered and were as secretive as an oyster about the genesis of your art already during your lifetime. Because, and this is crucial, you delivered in full in your notes. And we are the ones who have to say something about it, namely an enormous thank you! Thank you, dear Bach, for your constant zeal and all the fruits of your diligence, with which we are truly “blessed” until today.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).