Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut

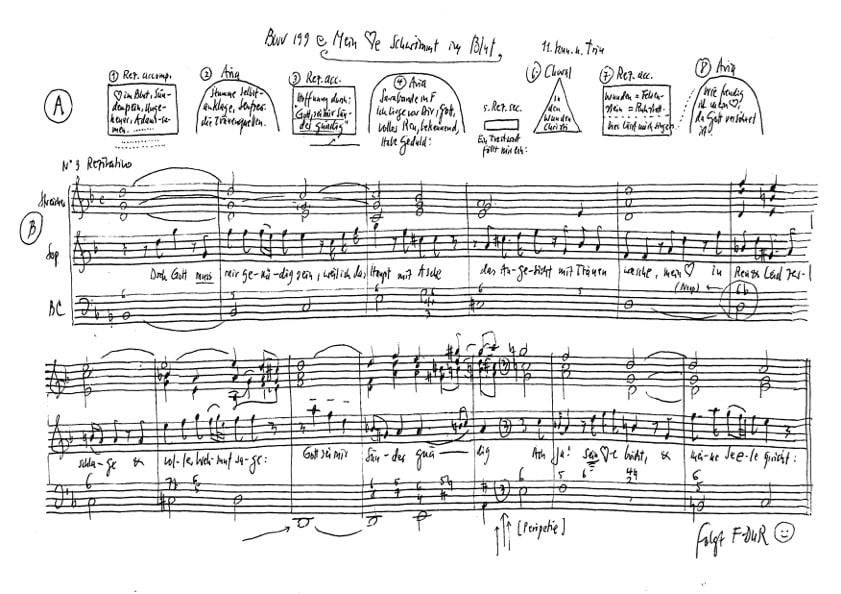

BWV 199 // for the Eleventh Sunday after Trinity

(My heart doth swim in blood) for soprano, oboe, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Theorbo

Fred Jacobs

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Emma Kirkby

Recording & editing

Recording date

23/11/2023

Recording location

Speicher AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

12 August 1714, Weimar

Text sources

Georg Christian Lehms (movements 1–5 and 7+8) Johann Heermann (movement 6)

Libretto

1. Rezitativ — Sopran

Mein Herze schwimmt im Blut,

weil mich der Sünden Brut

in Gottes heilgen Augen

zum Ungeheuer macht;

und mein Gewissen fühlet Pein,

weil mir die Sünden nichts als Höllenhenker sein.

Verhaßte Lasternacht,

du, du allein

hast mich in solche Not gebracht!

und du, du böser Adamssamen,

raubst meiner Seelen alle Ruh

und schließest ihr den Himmel zu!

Ach! unerhörter Schmerz!

Mein ausgedorrtes Herz

will ferner mehr kein Trost befeuchten;

und ich muß mich vor dem verstecken,

vor dem die Engel selbst ihr Angesicht verdecken.

2. Arie und Rezitativ — Sopran

Stumme Seufzer, stille Klagen,

ihr mögt meine Schmerzen sagen,

weil der Mund geschlossen ist.

Und ihr nassen Tränenquellen

könnt ein sichres Zeugnus stellen

wie mein sündlich Herz gebüßt.

Mein Herz ist itzt ein Tränenbrunn,

die Augen heiße Quellen.

Ach Gott! Wer wird dich doch zufriedenstellen?

3. Rezitativ — Sopran

Doch Gott muß mir genädig sein,

weil ich das Haupt mit Asche,

das Angesicht mit Tränen wasche,

mein Herz in Reu und Leid zerschlage

und voller Wehmut sage:

«Gott sei mir Sünder gnädig!»

Ach ja! sein Herze bricht,

und meine Seele spricht:

4. Arie — Sopran

Tief gebückt und voller Reue lieg ich,

liebster Gott, vor dir.

Ich bekenne meine Schuld,

aber habe doch Geduld,

habe doch Geduld mit mir!

5. Rezitativ — Sopran

Auf diese Schmerzensreu

Fällt mir alsdenn dies Trostwort bei:

6. Choral — Sopran

Ich, dein betrübtes Kind,

werf alle meine Sünd’,

so viel ihr’ in mir stecken

und mich so heftig schrecken,

in deine tiefen Wunden,

da ich stets Heil gefunden.

7. Rezitativ — Sopran

Ich lege mich in diese Wunden

als in den rechten Felsenstein;

die sollen meine Ruhstatt sein.

In diese will ich mich im Glauben schwingen

und drauf vergnügt und fröhlich singen.

8. Arie — Sopran

Wie freudig ist mein Herz,

da Gott versöhnet ist

und mir nach Reu und Leid

nicht mehr die Seligkeit

noch auch sein Herz verschließt.

Emma Kirkby

It is an honour and a pleasure for me to experience Bach Cantata 199 with you – with this inspiring ensemble.

What I have to say will be very personal, because I am neither a musicologist nor a theologian, but simply an enthusiast.

Bach offers us singers a marvellous balance of pleasure – one moment we are physically involved and the next we are listening spellbound to the commitment and skill of others; the singer is the happiest person in the room!

Thomas Morley, the English composer and theorist of the Renaissance, emphasised the great importance of the text for the singers and called it ” the living soul of music”; it should draw the listeners with golden chains to the contemplation of heavenly things.

This function of the text is also the only reason why the singers stand in the front row at a typical cantata performance, embedded in an ensemble of virtuoso musicians, all of whom play a decisive role in the interpretation of the work.

For singers, it is a joy to be an “instrument” among instruments!

However, it is important that the message of the work reaches the audience.

Bach’s obbligato parts demand beauty of tone and great skill from the instrumentalists, but also, as the treatises from the Renaissance onwards t, a certain “vocality” . I have often noticed this in the colleagues I have worked with: a musical eloquence attuned to the meaning and expression of the text; we musicians are all speakers and narrators.

I have spent a lifetime researching how I can best “embody” the texts , in all their diversity of expression and meaning.

Singers know that they have to use their whole body for an expressive performance. They work on body tension to maintain a beautiful line, a legato that connects the beautiful notes.

Attention is focussed on the vowels, sometimes unfortunately at the expense of the consonants, which are perceived as unpleasant interruptions. And so the primacy of the vocal line acts like a bulldozer, flattening all the consonants in its path.

The result is a serious loss of clarity, the text almost disappears in the marvellous sound… but what the heck: The audience has a text booklet in their hands! Even in Bach’s time, by the way…

When I started out as a young singer, I was as enthusiastic about the words as I was about the melody – I loved the complicated lyricism of John Dowland’s lute songs or the intricate stories of Renaissance rondeaux in three or more voices.

I was lucky enough to meet a wonderful singing teacher, Jessica Cash, who sadly passed away this summer. I owe her more than I can express.

On the very first day, she said to me: “Consonants are your best friends. They give you the best vowels! Every consonant should have a complete closure – because what doesn’t close properly t can’t open properly either…”

And about the Legato she said: “We all dream of a perfect Legato that runs smoothly and smoothly, like a Rolls Royce that magically glides along without any friction – but what actually drives this magical thing? A series of small explosions in the so-called combustion engine! And these explosions are our consonants, which give us our vowels, pure, bright and clear.”

So consonants are physically practical and effective things – they arise from emotions and they accompany emotions. When we are excited, shocked or angry, we react in English, and I think also in German, with strong consonants.

(an English example – …would be funny…)

We know that every intelligible speech requires the precise use of articulators: Lips, teeth, tongue.

But as soon as emotions arise, we need our whole body and should, as the saying goes, “speak from the heart” . And it is precisely the consonants, these apparent interruptions of the longed-for “legato line” , that come from the heart and lend our singing convincing emphasis.

These “consonant explosions” are also helpful for catching your breath.

If you only have a short moment to breathe, this will help:

You sing the preceding phrase with full energy and articulate the last consonant strongly and sensitively; this will activate your heart, your body tension and as a result you breathe briefly and dynamically – and lo and behold, the following syllable is full of power and energy! Now the ends of the word can also be heard well in a church.

I think that in this way you can retain Bach’s punctuation and sing the thought as naturally as if you were speaking it.

Many of Bach’s texts are emotionally charged – I would always go back to the consonants, because expressing these emotions requires full physical effort.

I have not yet mentioned a crucial physical means of expression: our hands!

They have a similarity to words and language; we talk with our hands in everyday life and even more so in important meetings when we have to react emotionally to a message or a new proposal, or when we have to put forward a plan or an argument of our own.

For centuries, training in rhetoric was part of every serious education, including that of Bach’s students in Leipzig. Among other things, they learnt to give a text persuasive power with the right gestures.

At a time when there was no electric light and no glasses for short-sighted people, people in the theatre and other public places were often unable to see the speakers’ faces clearly; meaningful gestures were therefore essential for communication.

The use of the hands also lends power and authority to the singing.

In Bach’s time, it was recommended to hold the hands at the level of the heart and make small gestures. This involves the whole body in conveying the message clearly and convincingly.

Even when singing from sheet music, the hands are at the level of the heart, can participate and expressively support the sound speech.

***

After these vocal considerations I would like to say a few words about Cantata 199, how I hear it and how I experience it.

It is dramatic and profound and yet very singable.

It is kindly written for the voice – but demands a total surrender to the emotions. It follows the journey of the heart and soul from the agonising awareness of sin to the overwhelming certainty of redemption.

The language is vivid at every point, with a succession of vivid images that demand complete dedication from the singer.

At the beginning, in the recitative, the singer freezes in horror, a monster fit only for hell and denied heaven; the heart is so “parched” that it has no chance of consolation – hidden from the eyes of God.

The first aria begins with a duet of anxious beauty in which the oboe and bass sob towards each other, the oboe with great leaps that turn into sighs, and the basses with waves of sorrow;

Then the singer comes and describes a paradox: She sighs and complains about her own sins, although her mouth is closed.

This is followed by a short seccor ecitative – with hot tears welling up from the heart, a direct plea to God: “Who will satisfy you?”

The next recitative answers this question, supported by all the strings:

“But God must be merciful to me” … when the sinner repents fully and completely, with ashes and tears.

This is followed by the plea: “God be merciful to me a sinner” , it is a memorable melody.

All this leads to an astonishing result: “Ah yes, his heart breaks, and my soul speaks…”

And this is followed by the central string aria, which is one of my absolute favourites.

She sets words of humble remorse in a solid triple time, like a solemn dance. Poignant dissonances and exclamations of remorse are woven into a comforting melody.

In the middle section, confessions of guilt alternate with fervent pleas for patience until the moment comes that is so unusual that I almost have no words for it: During the seventh and final petition, the light of redemption appears like the first rays of a sunrise.

From this point onwards, the journey of the heart and soul unfolds in ever more comforting and hopeful words.

The singer intones a chorale in which she casts all sins into the deep wounds of the Saviour – again over a rich and deeply soothing bass line.

The final recitative and the gigue overflow with joy and gratitude of the heart, “da Gott versöhnet ist” .

How fortunate it is for us tonight to hear this cantata a second time!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).