O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort

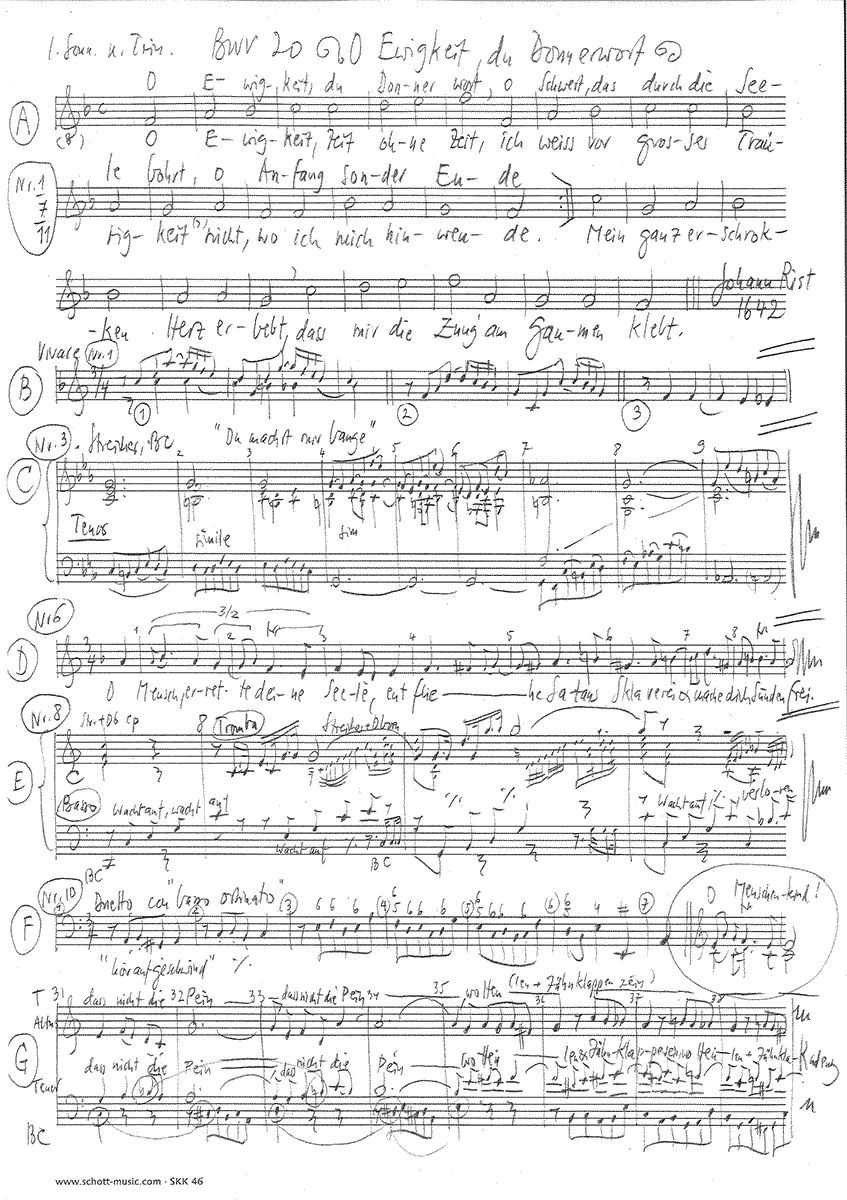

BWV 020 // For the First Sunday after Trinity

(Eternity, thou thundrous word) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I-III, tromba da tirarsi, trumpet, bassoon, strings and basso continuo

Cantata BWV 20, the first work in Bach’s second Leipzig cycle, was composed in 1724 for the First Sunday after Trinity. Based on a hymn by Johann Rist (1642), the libretto explores the theme of eternal damnation as told in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16), thus providing Bach with the framework for a veritable “music of terror” that torments the listener with the prospect of God’s eternal punishment while dramatically charging us to reform our ways and reject worldly pleasures.

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Meine Seele ist stille zu Gott, der mir hilft. Denn er ist mein Hort, meine Hilfe, mein Schutz, dass mich kein Fall stürzen wird, wie gross er ist.

Und wir haben erkannt und geglaubt die Liebe, die Gott zu uns hat. Gott ist Liebe; und wer in der Liebe bleibt, der bleibt in Gott und Gott in ihm. Darin ist die Liebe völlig bei uns, dass wir eine Freudigkeit haben am Tage des Gerichts; denn gleichwie er ist, so sind auch wir in dieser Welt. Furcht ist nicht in der Liebe, sondern die völlige Liebe treibt die Furcht aus; denn die Furcht hat Pein. Wer sich aber fürchtet, der ist nicht völlig in der Liebe. Lasset uns ihn lieben, denn er hat uns zuerst geliebt. So jemand spricht: «Ich liebe Gott», und hasst seinen Bruder, der ist ein Lügner. Denn wer seinen Bruder nicht liebt, den er sieht, wie kann er Gott lieben, den er nicht sieht? Und dies Gebot haben wir von ihm, dass wer Gott liebt, dass der auch seinen Bruder liebe.

Es war aber ein reicher Mann, der kleidete sich mit Purpur und köstlicher Leinwand und lebte alle Tage herrlich und in Freuden. Es war aber ein Armer mit Namen Lazarus, der lag vor seiner Tür voller Schwären und begehrte, sich zu sättigen von den Brosamen, die von des Reichen Tische fielen; doch kamen die Hunde und leckten ihm seine Schwären. Es begab sich aber, dass der Arme starb und ward getragen von den Engeln in Abrahams Schoss. Der Reiche aber starb und ward begraben. Als er nun in der Hölle und in der Qual war, hob er seine Augen auf und sah Abraham von ferne und Lazarus in seinem Schoss. Und er rief und sprach: «Vater Abraham, erbarme dich mein und sende Lazarus, dass er das Äusserste seines Fingers ins Wasser tauche und kühle meine Zunge; denn ich leide Pein in dieser Flamme.» Abraham aber sprach: «Gedenke, Sohn, dass du dein Gutes empfangen hast in deinem Leben, und Lazarus dagegen hat Böses empfangen; nun aber wird er getröstet, und du wirst gepeinigt. Und über das alles ist zwischen uns und euch eine grosse Kluft befestigt, dass die da wollten von hinnen hinabfahren zu euch, könnten nicht, und auch nicht von dannen zu uns herüberfahren.» Da sprach er: «So bitte ich dich, Vater, dass du ihn sendest in meines Vaters Haus; denn ich habe noch fünf Brüder, dass er ihnen bezeuge, auf dass sie nicht auch kommen an diesen Ort der Qual.» Abraham aber sprach zu ihm: «Sie haben Mose und die Propheten; lass sie dieselben hören.» Er aber sprach: «Nein, Vater Abraham! Sondern wenn einer von den Toten zu ihnen ginge, so würden sie Busse tun.» Er sprach zu ihm: «Hören sie Mose und die Propheten nicht, so werden sie auch nicht glauben, wenn jemand von den Toten aufstünde.»

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Guro Hjemli, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Damaris Rickhaus, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Elisabeth Kohler, Olivia Schenkel, Fanny Tschanz, Anita Zeller

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Ingo Müller, Shai Kribus

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Patrick Henrichs

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Sibylle Lewitscharoff

Recording & editing

Recording date

06/27/2014

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 7, 11

Johann Rist (1642)

Text No. 2–6, 8–10

Arranger unknown

First performance

First Sunday after Trinity,

11 June 1724

In-depth analysis

A particular characteristic of the chorale cantata cycle is the immediate introduction of the hymn text within the orchestral overture, a concept that Bach realises in exemplary fashion in the introductory chorus by creating two complementary planes of music. On the first, the arrival of the heavenly Lord and our fear of his judgement – the “sword that through the soul doth bore” – are depicted by the strings in the typical dotted rhythms and short, rapid figures of the French overture, while on the second, the oboes illustrate the word “eternity” through sustained long-notes in gradual, measured steps – a setting that not only achieves the scenic realism of the “thunderous word” but also captures the textual import and permanence of “eternity”. These planes prevail in constant thematic exchange between the instrumental groups almost throughout the entire movement and serve as a potent reminder that humans, in their fallibility, are perpetually torn between these conflicting spheres and that the dimension of “eternity” is ever-present as both a threat and a promise.

Bach integrates the chorale line for line into the orchestral material, reinforcing the soprano melody with a slide trumpet. When the lively triple time of the courtly overture emerges in the middle section (somewhat at odds with the sorrowful text and severe harmonies), humanity seems to be overwhelmed by the force of a punishing power, one that is just as much beyond its comprehension as the complexity of the fugue that is almost lost in the flowing music. After building up to an unexpected climax, a series of exclamations by the strings and woodwinds in contrary motion closes the movement, invoking a deep sense of horror. In the grip of this bodily experience of despair (“So much my frightened heart doth quake, that to my gums my tongue doth cake”) every remnant of peace and comfort has departed. It is difficult to conceive of an overture ending in F major ever expressing more devastating severity.

And yet the first recitative and tenor aria only serve to intensify the message of perpetual damnation (“endless time, thou mak’st me anxious”), with the ritornello of the aria taking up the sustained “eternity” motive of the overture, and the small intervals illustrating the trembling “anxiety”. In the B section, the spectre of hell is then conjured up in a flourish of baroque figures, yet the “flames which are forever burning” do not erupt from the orchestra, but from the soloist in a massive coloratura figure, evoking not only the judgement at the end of time but also revealing the mental processes of Bach’s extraordinary, and ultimately healing, creative genius.

With excessive power and eloquence, the ensuing bass recitative then contrasts time and eternity ere the bass aria justifies humankind’s self-inflicted torment in a dancelike, yet impassively dogmatic interpretation: “The Lord is just in all his dealings: the brief transgressions of this world, he hath such lasting pain ordained”. And, although the following alto aria “O man deliver this thy spirit” is a summons to “take flight from Satan’s slavery”, the vocalist can hardly break free from the resolute sarabande of the strings. Accordingly, the chorale verse leaves little scope for optimistic self-deception: “So long a God in heaven dwells, and over all the clouds doth swell, such torments will not be finished.”

Following this most terrifying sermon, the second part of the cantata continues in a similar vein, with the bass aria and its brilliant trumpet motives warning against “error’s slumber”. The recitative “Forsake, O man, the pleasure of this world” then numbers the ruinous sins under the threat of an untimely death, ere the alto and tenor, in a duet accompanied solely by succinct continuo figures, implore the worldly to see the error of their ways. Despite these well-meaning appeals, the allusion to the parable of the rich (every)man, the emphasis on the word “pain” in the harrowing opposition of the vocal parts, not to mention the closing chorale clearly reveal the threat of punishment to be omnipresent. Seen in this light, the abrupt turnaround in the final chorale line “take me then when thou dost please, Lord Jesus to thy joyful tent!” expresses a resigned acceptance that sorrow, pain and agony of the soul are never-ending in this world, and that it is beyond the power of humans alone to overcome them.

Libretto

Erster Teil

1. Chor

O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort,

o Schwert, das durch die Seele bohrt,

o Anfang sonder Ende!

O Ewigkeit, Zeit ohne Zeit,

ich weiss vor grosser Traurigkeit

nicht, wo ich mich hinwende.

Mein ganz erschrocken Herz erbebt,

dass mir die Zung am Gaumen klebt.

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Kein Unglück ist in aller Welt zu finden,

das ewig dauernd sei:

Es muss doch endlich mit der Zeit einmal verschwinden.

Ach! aber ach! die Pein der Ewigkeit hat nur kein Ziel;

sie treibet fort und fort ihr Marterspiel,

ja, wie selbst Jesus spricht,

aus ihr ist kein Erlösung nicht.

3. Arie (Tenor)

Ewigkeit, du machst mir bange,

ewig, ewig ist zu lange!

Ach, hier gilt fürwahr kein Scherz.

Flammen, die auf ewig brennen,

ist kein Feuer gleich zu nennen;

es erschrickt und bebt mein Herz,

wenn ich diese Pein bedenke

und den Sinn zur Höllen lenke.

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

Gesetzt, es dau’rte der Verdammten Qual

so viele Jahr, als an der Zahl

auf Erden Gras, am Himmel Sterne wären;

gesetzt, es sei die Pein so weit hinaus gestellt,

als Menschen in der Welt

von Anbeginn gewesen,

so wäre doch zuletzt

derselben Ziel und Maß gesetzt:

Sie müsste doch einmal aufhören.

Nun aber, wenn du die Gefahr,

Verdammter! tausend Millionen Jahr

mit allen Teufeln ausgestanden,

so ist doch nie der Schluss vorhanden;

die Zeit, so niemand zählen kann,

fängt jeden Augenblick

zu deiner Seelen ewgem Ungelück

sich stets von neuem an.

5. Arie (Bass)

Gott ist gerecht in seinen Werken:

Auf kurze Sünden dieser Welt

hat er so lange Pein bestellt;

ach wollte doch die Welt dies merken!

Kurz ist die Zeit, der Tod geschwind,

bedenke dies, o Menschenkind!

6. Arie (Altus)

O Mensch, errette deine Seele,

entfliehe Satans Sklaverei

und mache dich von Sünden frei,

damit in jener Schwefelhöhle

der Tod, so die Verdammten plagt,

nicht deine Seele ewig nagt.

O Mensch, errette deine Seele!

7. Choral

Solang ein Gott im Himmel lebt

und über alle Wolken schwebt,

wird solche Marter währen:

Es wird sie plagen Kält und Hitz,

Angst, Hunger, Schrecken, Feu‘r und Blitz

und sie doch nicht verzehren.

Denn wird sich enden diese Pein,

wenn Gott nicht mehr wird ewig sein.

Zweiter Teil

8. Arie (Bass)

Wacht auf, wacht auf, verlornen Schafe,

ermuntert euch vom Sündenschlafe

und bessert euer Leben bald!

Wacht auf, eh die Posaune schallt,

die euch mit Schrecken aus der Gruft

zum Richter aller Welt vor das Gerichte ruft!

9. Rezitativ (Altus)

Verlass, o Mensch, die Wollust dieser Welt,

Pracht, Hoffahrt, Reichtum, Ehr und Geld;

bedenke doch

in dieser Zeit annoch,

da dir der Baum des Lebens grünet,

was dir zu deinem Friede dienet!

Vielleicht ist dies der letzte Tag,

kein Mensch weiss, wenn er sterben mag.

Wie leicht, wie bald

ist mancher tot und kalt!

Man kann noch diese Nacht

den Sarg vor deine Türe bringen.

Drum sei vor allen Dingen

auf deiner Seelen Heil bedacht!

10. Arie (Duett Altus, Tenor)

O Menschenkind,

hör auf geschwind,

die Sünd und Welt zu lieben,

dass nicht die Pein,

wo Heulen und Zähnklappen sein,

dich ewig mag betrüben!

Ach spiegle dich am reichen Mann,

der in der Qual

auch nicht einmal

ein Tröpflein Wasser haben kann!

11. Choral

O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort,

o Schwert, das durch die Seele bohrt,

o Anfang sonder Ende!

O Ewigkeit, Zeit ohne Zeit,

ich weiß vor grosser Traurigkeit

nicht, wo ich mich hinwende.

Nimm du mich, wenn es dir gefällt,

Herr Jesu, in dein Freudenzelt!

Sibylle Lewitscharoff

No time for redemption?

The text of the cantata “O Eternity, Thou Word of Thunder” radicalises the possibility of divine punishment and speaks of the most terrible: the torments of sinful man can be infinite. The mystery of redemption seems far away, for the question of the hereafter remains unanswered and, translated into the here and now, becomes a question of conscience. Bach’s music, however, undermines the horror scenario and offers the reconciliation with which the word has such difficulty.

A monstrous text! Hardly reconciliatory, it has absolutely nothing of what today’s pastors and priests proclaim from their pulpits, no, rather not proclaim, but rather scatter among the people more or less casually as weak good news.

Here the weight of despair, the fear of the great reckoning is strong. But not only that, perhaps the fear is even greater that the reckoning and also the possible redemption could be delayed for all eternity. A deeply sinister thought, indeed.

The measure of time that is being taken into consideration here cannot really be grasped by man. Suppose the torment of the damned lasted longer than the earthly time envisaged through millennia. However, trembling and fright would then also be gone, for no human soul, in whatever state it may be after death, can be frightened and tremble for such an unceasingly long time. The conjured “thousand million years” are nothing here. Flying hell time, which at the same time bears the stamp of the everlasting. Terrible, terrible, if there is to be no end to the torment, no hope glimmering beneath that there will be an end to it one day.

It is, of course, a fright text, a fright cantata. It is meant to make sinful people repent in view of the almost infinite punishment that awaits the sinner in the background. For the sin is short, the life of the sinner is short, and the punishment imposed afterwards is all the longer.

In any case, redemption does not approach from eternity, on the contrary, it is the terribly stretched time in which no trustingly elevated state of being can be established, nothing similar to paradise, nothing that could even come close to the heavenly Jerusalem.

And in the middle of the chorale, there is a little crazy passage in which a thought flashes up that actually borders on blasphemy, for it says of the inhabitants of hell:

“They will be tormented by cold and heat,

fear, hunger, terror, fire and lightning.

and yet not consume them.

For this torment will come to an end

When God is no more eternal.”

“When God shall be eternal no more” is something a Christian had better not think of at all, it is almost blasphemy, even as a mere thought, for the substance of God consists precisely in His eternal existence from the beginning and into all time, with which something like a beginning of the divine existence is likewise extinguished, because His being stretches beyond it.

The horror, the torment of hell, even if they are musically hinted at – to capture them entirely in music is fundamentally difficult, the music is simply too beautiful for that, its euphony alone holds something redemptive in store, even if at the word “Donnerwort”, in order to evoke a little of the horror in the imagination, there is a sudden change to notes that follow one another quickly. If one did not know the text of the cantata and could not hear it in the song, one could freely imagine a glorious song of praise spiralling up to heaven, even singing of the delights of heaven after suffering.

In the Baroque era, people knew very well how to speak and sing of suffering. Despite its splendour, this period was also a time of darkness, in which the torment of the tormented human being was exhibited. The sweeping, curved forms in the churches, the much gold that was applied, could not hide this. This period was both great and gloomy. One only has to think of the Thirty Years’ War, which devastated the whole of Europe and depopulated huge swathes of land. The cantata is based on a hymn by Johannes Rist from 1642, when this unfortunate war was still in full swing. Later, some verses from it were used, and an unknown poet added the others.

Johann Sebastian Bach performed them for the first time in 1724, when the Thirty Years’ War was over, but its horrors must still have been vividly present in people’s memories. And these horrors were also very much alive in the imagination, in transformed fantasy form. It is not difficult to imagine how the suffering of the thousandfold maimed, the bitterly dead, the starved and the stricken by disease found their mental counterpart in tumultuous fantasies of hell.

God is presented as just in His works, but He is a punishing, inexorable God who does not forgive easily. There is also talk of the sword that He wields, a sword that bores through the soul of the sinner. And only at the very last, almost as if He had already been forgotten above all the punishments that come down on sinners and do not let them out of their clutches for a long, long eternity, does Jesus come into play – quite as if it were now being made up for, as if it were being remembered at the last moment that He still exists. And the desperate human being, who thinks his soul is already pierced by the sword of the judge, throws himself into Jesus’ arms or at least asks him to take care of him, because in Jesus the only hope is incarnated. In Jesus lives the promise of possibility that the sinner will escape the eternal torment of hell.

Above all, the hopeful man who loves the display of splendour is called up and reminded of his sins. That all this will be destroyed at once when man dies, that nothing of it will be found in the world beyond, is a traditional idea. It ties in with the Jesuan ideal of poverty, which says that the poor man will find a place in the kingdom of heaven much sooner than the rich man. The torment of the rich man is particularly illustrated here, for he feels an agonising thirst in hell and cannot even find a “drop of water”.

It is precisely the spring, the pure spring, from which the thirsty man drinks, that is often associated with Jesus Christ. Whoever is granted to drink from such a spring is already granted, as a sinful inhabitant of the earth, an ounce of purity, a tiny foretaste, as it were, of the purity and beauty of heaven.

The sinner should strive to emerge from the despair of eternity. The cantata is an artful threat, sounding in the sinner’s ears just in time for him to turn his evil life around. And the glorious music is the beautiful seductress to go with it. Music is rightly believed to have a deeper effect on the soul than all other arts, to be able to carry us up into another state of mind. And this different, refined and at the same time loosened state of mind is needed if such a difficult undertaking as the conversion of a sinner is to succeed.

I have no doubt that it is precisely the works of Johann Sebastian Bach that are capable of such a thing, if such a thing can be accomplished at all. With good reason, the composer is jokingly referred to as the fifth evangelist in the Protestant church. When I hear his St Matthew Passion in a church, I am close to tears in some places. There is a heartfelt art of persuasion at work, directed at the ears, which makes one imagine the stations of Jesus’ suffering more strongly, more intimately, than any picture panel, no matter how great, of which there are many.

It is true that I enjoy listening to a number of works of classical music, and Johann Sebastian Bach is my favourite, surpassing all other highly talented composers, but at the same time I feel little competent to talk about them. Because I had no musical upbringing and have never played an instrument, can only read a bit of music with a lot of difficulty. Nevertheless, Johann Sebastian Bach’s music touches me deeply. If I manage to give myself completely to it during a performance, I actually sense something like the possibility of seeming to be a better person, or at least a less bad person, and perhaps even of remaining so for a while. This may be an extremely naïve idea, but I am convinced that a musical masterpiece can also touch the childlike heart in the adult at the same time. It sets airy sails and is able to lead the mind to freer heights in which something like a delicate foretaste of redemption already drifts.

Great music is an enchanting, heart-bewitching dizziness; it can more easily tell of what we at best suspect, but about which we can know nothing in detail. Germs of hope blossom in it. Even if there is talk of pain and torment, and the tones bring sounds of pain to the ear. There is a power in her that overcomes the body. Sometimes it can even soften stony matter. Greek mythology has produced one of the most beautiful stories in this respect. Orpheus plays his lyre and the wild animals of the forest gather around him and listen attentively. All of a sudden, peace reigns among the creatures that would otherwise devour each other. There is even a legend about the famous singer that his song could even soften the stones. The Greeks knew it well: Paradise on earth, the magic of the Asphodelos meadows can be summoned most strongly by music. When I listen to “O Eternity, Thou Word of Thunder”, I don’t think so much about the punishments that may await me as an inveterate sinner for eons, how terribly stretched time is already stretched out over my head, time that “no one can count” and that will not be given a good ending, but I give myself to the music, give myself to the voices and feel something like a blissful being carried upwards that doesn’t quite want to fit the powerful threat of punishment. This music can’t help but give comfort through the painting of the hellish abandonment. And I willingly surrender to it.

And then there is this beautiful, renunciatory ending, sad, depressed, without momentum – “I know not for great sadness / Where I turn / Take me, if it please thee, / Lord Jesu, into thy tent of joy!” Perplexed melancholy prevails. Fear too. The weighted heart of man simply does not know what to do. And as if it could not continue to exist with its own heart, with its own soul, it hands over everything, everything that makes up the body, the spirit, the wandering thoughts, to Jesus Christ. And he should make everything good, wipe away the tears and lead us into his place of joy, no, not into a house, but into a tent that reminds us a little of a wedding tent stretched out on a flowering meadow.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).