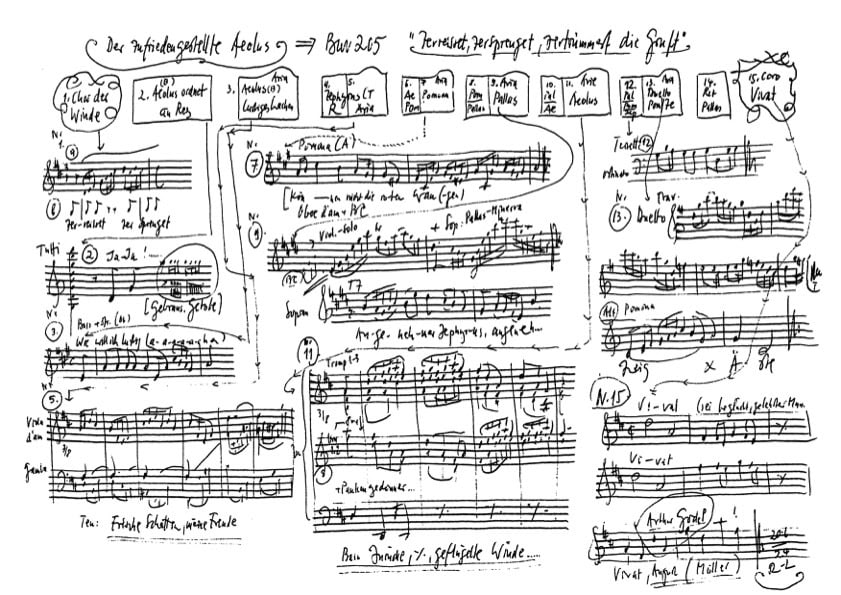

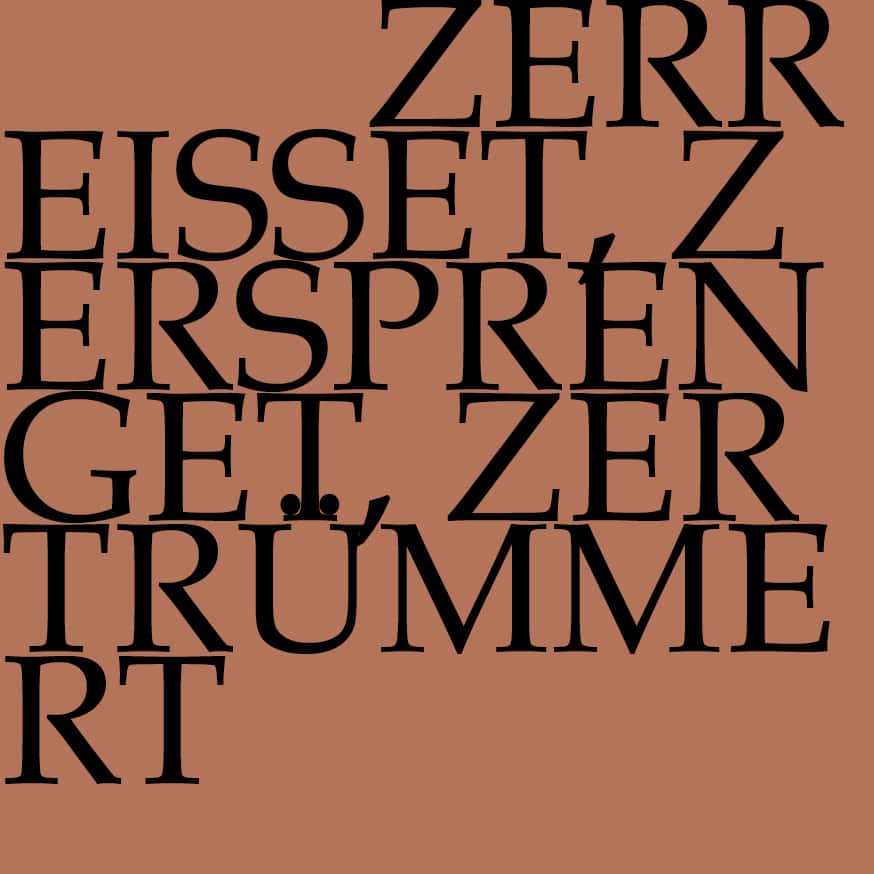

Zerreißet, zersprenget, zertrümmert die Gruft

BWV 205 // for the name day of Professor August Friedrich Müller (Dramma per musica)

(Demolish, disrupt it, destroy the lair) or the name day of Professor August Friedrich Müller (Dramma per musica), for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpets I-III, timpani, horn I+II, transverse flute I+II, oboe I+II, viola d’amore, viola da gamba, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Soprano

Ulrike Hofbauer

Alto

Claude Eichenberger

Tenor

Bernhard Berchtold

Bass

Dominik Wörner

Choir

Soprano

Alice Borciani, Cornelia Fahrion, Stephanie Pfeffer, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Antonia Frey, Tobias Knaus, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Zacharie Fogal, Joël Morand, Sören Richter

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, Peter Strömberg, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen, Dorothee Mühleisen, Judith von der Goltz

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sonoko Asabuki, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Viola da Gamba

Rebeka Rusó

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Rebekka Brunner

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Horn

Stephan Katte, Thomas Friedlaender

Trumpet

Jaroslav Rouček, Matthew Sadler, Alexander Samawicz

Timpani

Inez Ellmann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Arthur Godel

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Arthur Godel

Recording & editing

Recording date

28/06/2024

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Rudolf Steiner Schule

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First Performance

3 August 1725 – Leipzig

Text

Christian Friedrich Henrici 1725

In-depth analysis

The term “occasional works” used to describe the commissioned works Bach composed alongside his church music obligations does little justice to their artistic quality or compositional variety. Cantata BWV 205 is a case in point: written by the Thomascantor in August 1725 for the name-day of university professor August Friedrich Müller, the work breaks every mould in its ambition and range, marking a pinnacle among his dramatic compositions. The libretto by Henrici describing a celebration nigh blown away by the autumn winds provided a cast of contrasting characters; how Bach realised the musical setting, however, went above and beyond, as he once again transformed a one-off commission into an opportunity for artistic display.

The grandiose opening chorus unleashes a natural spectacle of sublime force; the winds, released from their summer lair, arrive in an orchestral prelude of rushing cascades and pounding quavers before swirling to the fore with wrathful cries and racing coloraturas. Here, Bach’s rare decision to assign individual parts to trumpets, horns, oboes and flutes in addition to the strings and timpani lends the movement a sonority capable of portraying all stages of a hurricane, through to the darkening of the sun.

Following this musical barrage, the wind god Aeolus sweeps into the bass recitative like an invincible general and, backed by the full orchestra, authorises his companions to put an end to summer with storms, floods and cold rains. The following aria “Wie will ich lustig lachen, wenn alles durcheinander geht” (How I will burst with laughter, when all is thoroughly confused), accompanied only by strings and an oboe, makes an amenable first impression with its compact, dance-like gesture. But Aeolus, who is evidently enjoying his rampage, reveals a disturbing energy when “die Dächer krachen” (the housetops shatter), illustrating how a deadly desire to destroy can lurk behind a sovereign’s polished smile.

The following pair of recitative and aria movements represents a first attempt at a diplomatic intervention. The south wind Zephyrus, portrayed by the tenor, conjures up the pleasures of a shady summer’s day to the noble duo-accompaniment of a viola da gamba and viola d’amore. But such elegiac music fails to fully persuade cold-blooded Aeolus to yield, and new intercessors are needed in the form of Pomona, goddess of the harvest, and Pallas, the personification of wisdom. Supported by a captivating oboe obbligato, Pomona’s aria seeks to elevate the “roten Wangen” (rosy cheeks) of ripe fruit, doubtless a double entendre, to a moment made for lingering. Yet it dawns on her, too, that such offerings will halt neither the fury of the wind god nor the passing of the seasons. Accordingly, Pallas Athene takes the lead in the ensuing duo recitative and then, in an aria with sweeping violin cantilenas and a delicate 12⁄8 pastoral gesture, begs the sabre-rattling Aeolus to allow her to continue caressing her beloved Zephyrus.

Alas, dreamy nostalgia alone has yet to placate the gods or those in political power. All the more important, then, to find their Achilles heel, which, in the following recitative, is unsurprisingly revealed to be the name of the cantata’s dedicatee. That the glowering misanthrope Aeolus then joins the singing of “mein Müller, mein August” (“my Müller, my August”), accompanied by shimmering flutes, would no doubt have raised a few smiles already in 1725.

Of course, a proud king does not suddenly abandon the battlefield. Rather, in his aria “Zurücke, zurücke, geflügelte Winde” (Retire now, retire now, ye wing-bearing tempests), Aeolus, accompanied by the full brass section, reasserts his true power by granting a reprieve. Here, the setting’s simple style and lilting 3⁄8 metre lend a courtly elegance to this heraldic display.

With the professor’s good name having restored the peace, the other protagonists can rejoice with newfound cheer in an arioso recitative, ere Zephyrus and Pomona unite in a duet with an obbligato flute to announce a feast replete with sweet treats and merry banter. In her final recitative, Pallas invites all present to join in the merrymaking but also reminds them of their duty to climb the “peaks of wisdom” in honour of their professor. While his endeavours for the benefit of scholarship and country are lauded in the quieter interludes of the closing chorus, they are nonetheless overshadowed by its exuberant tutti frame. That this final movement paid tribute to an untitled academic with cries of “Vivat August!” – and not the king of the same name – doubtless smacked of disrespect to some listeners. This was rectified by Bach in 1734 when he presented the cantata again to the new text of “Blast Lärmen, ihr Feinde” (Sound the alarm, you foes, BWV 205a) for the coronation of the king’s successor, Frederick Augustus II.

Libretto

1. Chor der Winde

Zerreißet, zersprenget, zertrümmert die Gruft,

Die unserm Wüten Grenze gibt!

Durchbrechet die Luft,

Daß selber die Sonne zur Finsternis werde,

Durchschneidet die Fluten, durchwühlet die Erde,

Daß sich der Himmel selbst betrübt!

2. Rezitativ — Bass (Aeolus)

Ja! ja! Die Stunden sind nunmehro nah,

Daß ich euch treuen Untertanen

Den Weg aus eurer Einsamkeit

Nach bald geschloßner Sommerszeit

Zur Freiheit werde bahnen.

Ich geb euch Macht,

Vom Abend bis zum Morgen,

Vom Mittag bis zur Mitternacht

Mit eurer Wut zu rasen,

Die Blumen, Blätter, Klee

Mit Kälte, Frost und Schnee

Entsetzlich anzublasen.

Ich geb euch Macht,

Die Zedern umzuschmeißen

Und Bergegipfel aufzureißen.

Ich geb euch Macht,

Die ungestümen Meeresfluten

Durch euren Nachdruck zu erhöhn,

Daß das Gestirne wird vermuten,

Ihr Feuer soll durch euch erlöschend untergehn.

3. Arie — Bass

Wie will ich lustig lachen,

Wenn alles durcheinandergeht!

Wenn selbst der Fels nicht sicher steht

Und wenn die Dächer krachen,

So will ich lustig lachen!

4. Rezitativ — Tenor

Gefürcht’ter Aeolus,

Dem ich im Schoße sonsten liege

Und deine Ruh vergnüge,

Laß deinen harten Schluß

Mich doch nicht allzufrüh erschrecken;

Verziehe, laß in dir,

Aus Gunst zu mir,

Ein Mitleid noch erwecken!

5. Arie — Tenor

Frische Schatten, meine Freude,

Sehet, wie ich schmerzlich scheide,

Kommt, bedauret meine Schmach!

Windet euch, verwaisten Zweige,

Ach! ich schweige,

Sehet mir nur jammernd nach!

6. Rezitativ — Bass

Beinahe wirst du mich bewegen.

Wie? seh ich nicht Pomona hier

Und, wo mir recht, die Pallas auch bei ihr?

Sagt, Werte, sagt, was fordert ihr von mir?

Euch ist gewiß sehr viel daran gelegen.

7. Arie — Alt

Können nicht die roten Wangen,

Womit meine Früchte prangen,

Dein ergrimmtes Herze fangen,

Ach, so sage, kannst du sehn,

Wie die Blätter von den Zweigen

Sich betrübt zur Erde beugen,

Um ihr Elend abzuneigen,

Das an ihnen soll geschehn.

8. Rezitativ — Alt, Sopran

Alt

So willst du, grimmger Aeolus,

Gleich wie ein Fels und Stein

Bei meinen Bitten sein?

Sopran

Wohlan! ich will und muß Auch meine Seufzer wagen,

Vielleicht wird mir,

Was er, Pomona, dir

Stillschweigend abgeschlagen,

Von ihm gewährt.

{Sopran, Alt}

Wohl! wenn er gegen {mich, dich} sich gütiger erklärt.

9. Arie — Sopran

Angenehmer Zephyrus,

Dein von Bisam reicher Kuß

Und dein lauschend Kühlen

Soll auf meinen Höhen spielen.

Großer König Aeolus,

Sage doch dem Zephyrus,

Daß sein bisamreicher Kuß

Und sein lauschend Kühlen

Soll auf meinen Höhen spielen.

10. Rezitativ — Sopran, Bass

Sopran

Mein Aeolus,

Ach! störe nicht die Fröhlichkeiten,

Weil meiner Musen Helikon

Ein Fest, ein‘ angenehme Feier

Auf seinen Gipfeln angestellt.

Bass

So sage mir:

Warum dann dir

Besonders dieser Tag so teuer,

So wert und heilig fällt?

O Nachteil und Verdruss!

Soll ich denn eines Weibes Willen

In meinem Regiment erfüllen?

Sopran

Mein Müller, mein August,

Der Pierinnen Freud und Lust

Bass

Dein Müller, dein August!

Sopran

Und mein geliebter Sohn,

Bass

Dein Müller, dein August!

Sopran

Erlebet die vergnügten Zeiten,

Da ihm die Ewigkeit

Sein weiser Name prophezeit.

Bass

Dein Müller! dein August!

Der Pierinnen Freud und Lust

Und dein geliebter Sohn,

Erlebet die vergnügten Zeiten,

Da ihm die Ewigkeit

Sein weiser Name prophezeit:

Wohlan! ich lasse mich bezwingen,

Euer Wunsch soll euch gelingen.

11. Arie — Bass

Zurücke, zurücke, geflügelten Winde,

Besänftiget euch;

Doch wehet ihr gleich,

So weht doch itzund nur gelinde!

12. Rezitativ — Sopran, Alt, Tenor

Sopran

Was Lust!

Alt

Was Freude!

Tenor

Welch Vergnügen!

alle

Entstehet in der Brust,

Daß sich nach unsrer Lust

Die Wünsche müssen fügen.

Tenor

So kann ich mich bei grünen Zweigen

Noch fernerhin vergnügt bezeigen.

Alt

So seh ich mein Ergötzen

An meinen reifen Schätzen.

Sopran

So richt ich in vergnügter Ruh

Meines Augusts Lustmahl zu.

Alt, Tenor

Wir sind zu deiner Fröhlichkeit

Mit gleicher Lust bereit.

13. Arie — Alt, Tenor

Alt

Zweig und Äste

Zollen dir zu deinem Feste

Ihrer Gaben Überfluß.

Tenor

Und mein Scherzen soll und muß,

Deinen August zu verehren,

Dieses Tages Lust vermehren.

{Alt, Tenor}

Ich bringe {die Früchte, mein Lispeln} mit Freuden herbei,

beide

Daß alles zum Scherzen vollkommener sei.

14. Rezitativ – Sopran

Ja, ja! ich lad euch selbst zu dieser Feier ein:

Erhebet euch zu meinen Spitzen,

Wo schon die Musen freudig sein

Und ganz entbrannt vor Eifer sitzen.

Auf! lasset uns, indem wir eilen,

Die Luft mit frohen Wünschen teilen!

15. Chor

Vivat August, August vivat,

Sei beglückt, gelehrter Mann!

Dein Vergnügen müsse blühen,

Daß dein Lehren, dein Bemühen

Möge solche Pflanzen ziehen,

Womit ein Land sich einstens schmücken kann.

From Arthur Godel

Reflection on the cantata BWV 205 “The Satisfied Aeolus”

Bach as a teacher

With today’s cantata, Leipzig students thanked an esteemed teacher, the law and philosophy lecturer August Friedrich Müller. For his 35th name day (Augustus), they commissioned a festive open-air cantata from the city’s first composer. Truly a sympathetic gesture of thanks!

It makes me think about Bach as a teacher. He worked for 27 years at the elite music school in the commercial city of Leipzig and as a composer he remains one of the great teachers to this day.

So I asked myself:

- How did Bach himself learn and how did he teach?

- What has he taught us, what has he taught me?

How it started for me

For me, it started (quite unnoticed) with Gounod! As a young violinist, I played his “Ave Maria” and only later discovered that this was my first Bach. I grew up with Mozart and Schubert, Bach came later. The de-Romanticised Baroque music I heard on the radio in our living room in my youth was labelled “sewing machine Baroque”. And that’s how some of it sounded.

Fortunately, a rebel like Harnoncourt soon came along and the historically-informed, so-called authentic style of playing was introduced. New life was breathed into baroque music. We all owe a great deal to historical Baroque and Bach research, and thanks to the performers who have been inspired by it, we are hearing Bach anew. I am thinking of Angela Hewitt, András Schiff, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Rudolf Lutz and many others.

From Vivaldi to Bach

However, my approach to Bach took a diversion via Vivaldi! As a young music student, I was given the opportunity to play Bach’s “A minor Concerto” as a soloist. In the large hall of the Grand Hotel on the Seelisberg, directly above the Rütli, in the hall where orange-robed gurus later taught transcendental meditation.

The music of the “A minor concerto” sounded familiar to me, as I had already played my way through countless Vivaldi concertos. I later discovered that Bach had also studied Vivaldi thoroughly and had even turned Vivaldi’s violin concertos into a one-man show for an organist. Bach owed the concertante vigour of many of his works to the Italians.

I was particularly moved by the slow movement of the Violin Concerto in A minor. Here, the solo violin floats above a firm, ostinato bass, free as a bird in the sky – it was highly expressive music. For the first time, I encountered Bach’s gripping expressiveness, which I would experience in an overwhelming variety years later in our cantata project. Not the gurus from Seelisberg, but Bach led me to a kind of transcendental meditation – or to put it more simply: to a fulfilled inwardness when listening to his music.

Polyphonic for violin solo

When I entered the conservatory, the sonatas and partitas for solo violin were on the study programme. I got closer to Bach by playing him. “Interpreting music: Make music”. I found this sentence by Adorno confirmed again and again (from: Fragment on Music and Language).

So now the solo sonatas, this artful polyphony for a monophonic instrument. In the not very extensive repertoire for solo violin, Bach’s “Chaconne” remains unrivalled for me, a cathedral of sound in 64 variations. The “Chaconne” is devilishly difficult. I was not surprised when I later learnt that Bach himself was an accomplished violinist – and he was also a highly productive learner in this case. A few contemporary virtuosos had already taken polyphonic playing on the monophonic instrument a long way; Bach, however, was the first to compose truly great music with it.

Ingenious learning ability

That’s how I see him: he learnt wherever he found something outstanding:

- as a young organist and composer with the old German organ masters Reincken and Buxtehude

- later the concertante style of Vivaldi

- the musical rhetoric of Schütz

- and finally even in his most talented sons the new style of sensibility!

Bach’s genius was also based on an ingenious ability to learn – and the ambition to further develop and surpass his role models. He used his sharp musical thinking to achieve this.

The rational stream

Bach was a highly rational composer. In the spirit of Kant, he achieved a high degree of compositional autonomy through radically independent thinking. The intellectual depth with which a musician reads the Bible and how he translates his insights and his faith into musical images that can be experienced by the senses is historically unique – against the backdrop of a skilfully crafted musical setting. Just think of the opening chorus of the St Matthew Passion, for example, about which books could be written, or the polyphonic marvels of many choral movements in the cantatas. Bach explored everything that was musically possible at the time, expanded and varied the cantata form many times and even flirted with opera, which did not (or no longer) exist as an institution in Leipzig at the time. The cantata in today’s concert, explicitly labelled as a “dramma per musica”, is an example of this.

Ordo and harmony

I also had to discover the rational Bach first. I was helped by a teacher at the conservatory, Peter Benary, a musicologist and composer from Thuringia, Bach’s neighbourhood. He showed us, for example, the construction plans on which Bach’s works are based: On a large scale, for example, the axially symmetrical arrangement in the Credo of the “Mass in B minor”, or on a smaller scale the balanced motivic interplay in the Inventions.

I now realised why I feel so uplifted when listening to Bach’s music; it is this order that prevails over everything and creates harmony. In the understanding of the time, it was the image of the divine order, but it continues to have an effect even today with a changed world view. Why this is so remains a mystery to me, but it is a fact.

A happy time back then, which – as the philosopher Leibniz put it – was convinced: “God has recognised the best of all worlds through his wisdom, chosen it through his goodness and realised it through his power.” It is this happiness of an ordered, harmonious universe that we experience and perhaps also seek in Bach’s music. Before we return to a completely different world …

Inventions

Back to the conservatory again: the lessons went one step further from analysis to practice, and we were asked to write short piano pieces in the style of Bach’s two-part Inventions. Only then did we realise how foresightedly Bach had set his themes, already keeping all contrapuntal variations in mind, and how elegantly, even expressively and never schematically he developed these “Inventiones”. How awkward and angular our attempts were in comparison.

Bach wrote the Inventions (which you may also have played at some point) for the piano and composition lessons of his eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann.

Passionate pedagogue

Bach was a passionate pedagogue and systematic composer, as is typical of German Baroque composers. However, none of his contemporaries created such a large series of pedagogical works, which are also great music, for example:

- the inventions

- the Well-Tempered Clavier

- the Orgelbüchlein (the great school of chorale arrangements).

He presented these three collections of works when he applied to Leipzig as proof of his pedagogical skills as a piano and composition teacher. He moved to Germany’s most renowned university city. The Enlightenment thinkers there focussed entirely on pedagogy – pedagogy as the best way to self-development and intellectual independence. This was also the case for August Friedrich Müller, the lecturer honoured with our cantata.

Bach remained his own teacher for the rest of his life, or to use the language of sport, his only challenger. When the famous French organist Marchand was to compete with him and Bach heard about it, he left the field in a hurry. He quickly realised that Bach was and remained in a class of his own.

Consistency and universality

The technique of counterpoint, of which he was the undisputed master, remained the epitome of musical erudition far beyond the Baroque period – from Mozart to Mendelssohn, from late Beethoven to Brahms and perhaps to this day. However, it is not only his mastery of compositional technique that draws composers and us today to Bach:

It is the coherence of his music.

It is the universality of his music.

It speaks directly to us across the centuries.

And asks the big, unanswerable questions.

It remains open to new interpretations.

Bach’s complete vocal works

Over the years, we have experienced the almost inexhaustible wealth of Bach in our large Bach project. The multidimensionality and depth of his vocal work was revealed to us: didactically, musically and theologically. Over 200 cantatas, and each one is always new!

Even the baroque cantata texts, to which Bach gave his interpretation, became the key to big questions for us. Thanks to our two “teachers”, the well-educated theologians Karl Graf and Niklaus Peter. Our reflectionists also play a part. Starting from a key word in the cantata, they build a bridge to the present, as I have tried to do today with the topic of “Bach as a teacher”.

My thanks

I was able to experience fifteen years of Bach cantatas with you; it was the most valuable listening school of my life. Realised by a passionate teacher, a conductor, dear Ruedi, who takes the royal road of musical didactics anew every month: the direct connection between the explanatory word and the music that can be heard.

Truly, your introductions and above all your interpretations offer us the masterclass of a highly versatile musician. You have the musical language of Bach down pat and speak it as an improviser and composer.

A big thank you also to all of you, singers and musicians, you open up Bach to us with great skill and dedication – the spark jumps over to us. Understanding and enjoying Bach requires performers of your quality!

Nevertheless, with no other composer do I have the feeling that I still don’t fully understand him. Bach remains a life project. We are in good company. Carl Friedrich Zelter, Goethe’s musical advisor and patron of Mendelssohn, spent a lifetime studying Bach. He came to the conclusion:

“Bach clear – but ultimately inexplicable.”

(Many thanks to Kerstin Wiese from the Bach Archive Leipzig for her expert review of the speech)

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).