Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe

BWV 022 // For Estomihi

(Jesus took to him the twelve) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe, strings and continuo

“Note: this is the audition piece for Leipzig” – this note by one of Bach’s Leipzig copyists on BWV 22 “Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe” (Jesus took to him the twelve) confirms that this cantata was composed as part of Bach’s application for the position of Thomascantor. It is worth noting that the appointment of Bach, at that time Kapellmeister in Köthen, was not as self-evident as his posthumous fame would imply. In fact, following the death of Bach’s predecessor, Johann Kuhnau, on 5 June 1722, it was Georg Philipp Telemann, well-connected in Leipzig since his student days, who was initially sought for the post. It was not until Telemann declined the position that a formal application process for composers outside of Leipzig commenced. From the field of applicants, it was Bach and Johann Christian Graupner from Darmstadt who eventually received the opportunity to present two cantatas at a church service. Bach was assigned the occasion of Estomihi (the Sunday before Lent) on 7 February 1723 and completed the major part of his compositions in Köthen: the aforementioned BWV 22 for the sermon and BWV 23 “Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn” (Thou, very God and David’s son) for Communion.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Valentin Parli, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

John Holloway (special Guest), Renate Steinmann

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Stefanie Haegele

Bassoon

Dorothy Mosher

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Ingrid Grave

Recording & editing

Recording date

02/19/2010

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Quote from Luke 18

Text No. 2–4

Poet unknown

Text No. 5

Elisabeth Creutziger, 1524

First performance

Estomihi,

7 February 1723

In-depth analysis

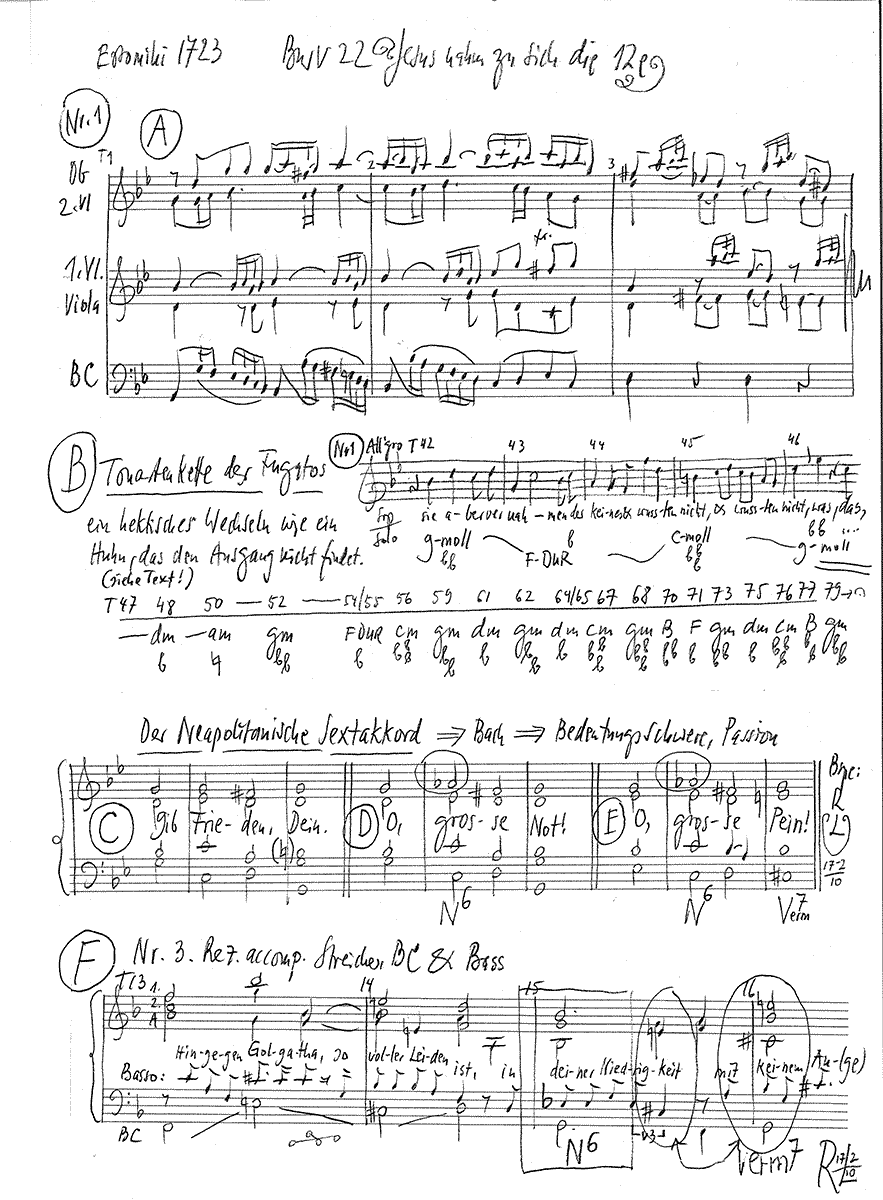

What is it that made “Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe” such an appropriate audition piece, and what vision of a “well-formed church music” (as the composer himself put it in 1730) made Bach a prime candidate in Leipzig where he was relatively unknown?

Firstly, Bach chose to compose a short, but colourful work of five diverse movements, each with a distinct character: a tutti opening with solo episodes, followed by an alto aria with obbligato oboe, a bass accompagnato with strings, a dance-like tenor aria with violins and viola, and a closing chorale with an independent orchestral underlay. Despite its clear formal development and melodic treatment, however, the work is not schematically conceived, and even the modified da capo aria shows remarkably inventive features.

In composing the opening movement, Bach skilfully avoided the pitfalls lurking in the li-bretto. While others may have artlessly misread the opening text and set it for tutti choir, Bach commences with a brief prelude of strings and solo oboe whose leitmotif introduces the theme of the phrase “We shall go up to Jerusalem”. A solo tenor then enters and, after a brief appearance, passes the floor to the bass, who, in Bach’s oeuvre, is often employed to deliver Christ’s word. Interestingly, in the tenor part, Bach suggestively stretches the word “twelve”, in reference to Christ’s disciples, over exactly twelve semiquavers. The bass arioso is then taken over by a four-part choral fugue, with the accompanying instruments entering last. The fact that Bach differentiates here between solo vocalists and supporting tutti singers explains why the usual practice of performing this section with a choir remains a contentious issue among specialists. In the concluding section, the disciples’ confusion described in the text is skilfully evoked through the use of abrupt pauses and tritone intervals – the greatest dissonance in baroque harmony. Finally, it is perhaps no great coincidence that the formal development of this movement, with its gradual intensification, mimicked the style of the immensely fashionable Telemann.

After this weighty first movement, the following aria “My Jesus, draw me unto thee” is a smoothly flowing trio of oboe, alto, and continuo, with which Bach aspired to demonstrate his abilities as a serious church composer. The recitative composition was a crucial requirement for such a posting, and Bach demonstrates his singular mastery of this element in the movement “My Jesus, draw me on”. Through its underlying string accompaniment, broad harmonic range and graceful solo voice, Bach succeeds in drawing out every facet of the text. Following these earnest tones, the lively minuet of the aria “My treasure of treasures” is rather folksy in character, while Bach’s melody for the closing chorale is downright catchy: strings and an oboe dance lightly over a cheerful bass, resulting in a remarkably tranquil melody despite the continuous semiquaver movement. Presented with such grace, the ponderous verse “Us mortify through kindness, awake us through thy grace” by Elisabeth Cruciger (1524) is rendered distinctly welcoming.

Bach’s audition piece for Estomihi of 1723 won over its audience with engaging melodies and formal precision without belying the composer’s superior skill. Nonetheless, it is entirely possible that only upon hearing his inaugural cantata of summer 1723 – a mammoth and highly experimental work – did the good citizens of Leipzig receive their first inkling as to the true extent of Bach’s artistic intentions.

Libretto

1. [Arioso und Chor] (Tenor, Bass, Chor)

Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe und sprach:

(Bass)

Sehet, wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem,

und es wird alles vollendet werden,

das geschrieben ist von des Menschen Sohn.

(Chor)

Sie aber vernahmen der keines und wussten

nicht, was das gesaget war.

2. Arie (Alt)

Mein Jesu, ziehe mich nach dir,

ich bin bereit, ich will von hier

und nach Jerusalem zu deinen Leiden gehn.

Wohl mir, wenn ich die Wichtigkeit

von dieser Leid- und Sterbenszeit

zu meinem Troste kann durchgehends

wohl verstehn!

3. Rezitativ (Bass)

Mein Jesu, ziehe mich, so werd ich laufen,

denn Fleisch und Blut verstehet ganz und gar

nebst deinen Jüngern nicht, was das gesaget

war.

Es sehnt sich nach der Welt und nach dem

grössten Haufen.

Sie wollen beiderseits, wenn du verkläret

bist,

zwar eine feste Burg auf Tabors Berge bauen;

hingegen Golgatha, so voller Leiden ist,

in deiner Niedrigkeit mit keinem Auge

schauen.

Ach! kreuzige bei mir in der verderbten Brust

zuvörderst diese Welt und die verbotne Lust,

so werd ich, was du sagst, vollkommen wohl

verstehen

und nach Jerusalem mit tausend Freuden

gehen.

4. Arie (Tenor)

Mein alles in allem, mein ewiges Gut,

verbessre das Herze, verändre den Mut;

Schlag alles darnieder,

was dieser Entsagung des Fleisches zuwider!

Doch wenn ich nun geistlich ertötet da bin,

so ziehe mich nach dir in Friede dahin!

5. Choral

Ertöt uns durch dein Güte,

erweck uns durch dein Gnad;

den alten Menschen kränke,

dass der neu’ leben mag wohl hie auf dieser Erden,

den Sinn und all Begehren

und G’danken hab’n zu dir.

Sr. Ingrid Grave

“That the new man may live”

“Jesus took to himself the twelve” – the hope of closeness at the time of death is the hope of life.

“Jesus took to himself the twelve” is the title of this evening’s cantata and this is also how its text begins. The words were recorded by the evangelist Luke. Who are the twelve? They are those men whom Jesus himself had chosen from the large circle of disciples and drawn into his immediate vicinity. Not now, shortly before his suffering, but earlier. He trusts these men to be able to endure the coming days of terror. “Behold, we go up to Jerusalem, and all things shall be accomplished (…)”. But they did not understand “what was said there.”

For who wants to understand the approaching catastrophe that is announced in a veiled way? In Jerusalem “all things will be accomplished that are written of the Son of Man”. What was written in the Holy Scriptures? Did the Twelve know it so well? Hardly! At least they could not make the connection between what was written and what was going on around them.

What was written, and what is written today? Printed for us and printed out on an infinite amount of paper! What could threaten us is spread out before our eyes every day. Or actually threatens us! We are only too happy to leave it where it is written! Regardless of this, we continue to walk doggedly, bravely or with slightly hidden resignation towards our Jerusalem! Or are we simply going because we have always been going in that direction?

Written almost two millennia ago, lifted up into my time, into our time, the biblical word gains a topicality, a liveliness that is alive to me, that is alive to us. We are already in the midst of it! The biblical word is followed by a text that in its language and style no longer seems to pass our lips. The unknown poet takes up what is written in the Bible and draws these words into his own life. He knows – unlike the Twelve – what will happen in Jerusalem, or more precisely, what happened there a long time ago. He is aware that just like the Twelve, I can miss the point because I am afraid to understand “what was said”. And not only because I am afraid, but also because I may refuse to accept the whole event – it is too terrible!

The demand and challenge is to enter into suffering with this Jesus. But it is important here to approach the text with attentiveness: Jesus did not demand. His words are rather a cautiously expressed expectation or request: Do not leave me alone in my humiliation. Jesus’ closest confidants hear it with their ears, but the words do not fall down into their hearts.

“My Jesu, draw me (…)”, now prays the unknown poet of the first cantata stanzas. In other words: Touch my heart! Only where the heart is touched does the strength of faithfulness to a person who has to go through suffering grow. Then “I will run” for this person, with this person – to the place of his suffering.

When my “flesh and blood” resists learning to understand and accept my own and other people’s suffering as reality, then, Jesus, pull me out of the “biggest pile”! I see him before me, this “heap”, this “greatest”, general. It is comfortable to run with it. In the general trend, suffering has neither meaning nor value. Happy is he who can suppress what is miserable in order to “build himself a strong fortress on Tabor’s mountains”.

The biblical Mount Tabor is the epitome of rapture and being taken out of worries, stress and everyday troubles. At least that is how it was understood by Peter, James and John. They are three of the twelve. Once Jesus had taken them aside and climbed Mount Tabor with them (cf. Matthew 17:1-9; Mark 9:2-9; Luke 9:28-36). Jesus prayed, and in praying his appearance changed. Jesus’ friends experience him in a light-transfigured state and see him in conversation with the two long-dead prophets Moses and Elijah. This experience triggers a confusion in Peter, James and John, a hovering between emotion, admiration and fear.

It is Peter who seems to be the first to get hold of himself: he wants to stay here, not go down from this mountain any more. He expresses his feelings and his longing: “It is good to be here, we want to build three huts here. – But this remains a wish! It is Jesus himself who descends from the mountain with the three. At that time they do not yet know how their revered Master will end and what valley of disappointment and dejection they will then have to walk through.

But now they turn their feet towards Jerusalem, perhaps already filled with the first dim suspicions that with the death of Jesus they too will have to bury all their illusions and fantasies of power there. Except for one – so the Bible reports – all the men of his trust abandoned their master Jesus at the decisive moment and took flight. The poet of the Bach cantata virtually pleads for the power of faithfulness. He knows too well that his “flesh and blood (…) Golgotha, (which) is so full of suffering, (…) will not look with any eye”. He asks for “spiritual mortification”. What – for God’s sake – should or must be “slain” in us in order for us to attain salvation? In fact, salvation and healing are not meant here as a consolation to an afterlife, under which modern man is less and less able to imagine anything.

It seems to me that “spiritual death” is about what we intellectual people narrow-mindedly and stubbornly squeeze into our plans. Everything is possible if transparent planning and competent advice go hand in hand. The head even knows how to block out an impending crisis in this respect for a long time. In this way, we can pass by Golgotha for years and decades, always new and different on the flight from Jerusalem. The head with its clever mind continuously invents and produces ingenious tricks to bypass Jerusalem. Something has to be prevented here, even “killed”, so that the heart and mind can speak to us again. The repression, the not wanting to be true, must be “killed” – for God’s sake. For it is God who lives in the bottom and abyss of our heart. Mysticism has always known this. We, on the other hand, know perfectly how to suppress what wants to rise from the depths of our heart: healing and salutary intuition, which can sometimes taste bitter.

This “my eternal good”, “my all in all” tells us to step out of the “biggest pile” and to dare the individual path into suffering. That takes courage! But the “eternal good” in me will equip me with the necessary courage, with strength and faithfulness. The fruit will be peace and the poet implies this: “So draw me after you in peace!” Peace was hardly what the Twelve had in their loopholes while their Master – far from them – bled to death on the cross in agony and loneliness.

Even if each person ultimately has to die their own death in their own loneliness, I believe it will be a comfort and help to me if someone is there to give me their closeness in these hours.

The text for the final chorale of the cantata was penned by a woman, the hymn poet Elisabeth Creutziger, who lived in the 16th century. This may be a coincidence. In the last hours of his life, some women, some disciples, were standing near the cross on which Jesus was hanged. This was probably no coincidence. They had obviously understood what was written and “what was said there”. But maybe not! They had simply followed their hearts. The heart sets out – without many questions – on the way to and with a person who is thrown into suffering.

“Awaken us through your grace”, says Elisabeth Creutziger. This – I think – had happened with the women. Grace had driven them – probably as a healing restlessness – to Jesus’ tomb on the third day. That was early in the morning, when it was still dark and the “biggest crowd” was still asleep. What they experience is transformation. They experience the dead as alive. He speaks a word of peace to them. The word of peace, the “Fear not”, is salvation and healing, it transforms their confused and traumatised psyche. “Mortify the old man, that he may live anew (…)”. Their souls were offended to the point of death, but now the women go into their new lives healed – with faith in life itself.

“That the ‘new’ (man) may live well here on this earth”, that is the wish of the 16th century cantata poet. The man of the 21st century, if he let his deepest longing speak, would hardly wish for anything else.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).