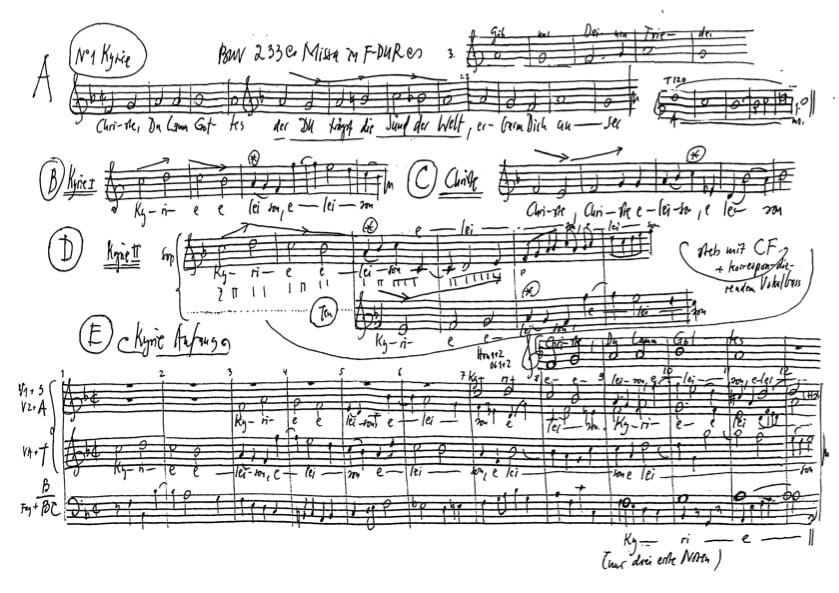

Messe F-Dur

BWV 233 //

(Mass in F Major) for soprano, alto and bass, vocal ensemble, horn I+II, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Simone Schwark, Mirjam Wernli, Lia Andres, Cornelia Fahrion, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad

Alto

Tobias Knaus, Antonia Frey, Lisa Weiss, Lea Scherer, Francisca Näf

Tenor

Sören Richter, Christian Rathgeber, Klemens Mölkner, Zacharie Fogal

Bass

Philippe Rayot, Christian Kotsis, Israel Martins, Tobias Wicky, Daniel Pérez

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Judith von der Goltz, Aliza Vicente

Viola

Sonoko Asabuki, Lucile Chionchini, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Horn

Stephan Katte, Thomas Friedländer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Jörg Frey

Recording & editing

Recording date

14/09/2023

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Cathedral

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

1738/1739 – Leipzig

Libretto

Kyrie

1. Chor

Kyrie eleison,

Christe eleison,

Kyrie eleison.

Gloria

2. Chor

Gloria in excelsis Deo,

et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Laudamus te, benedicimus te,

adoramus te, glorificamus te.

Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

3. Arie — Bass

Domine Deus, Rex coelestis,

Deus Pater omnipotens,

Domine Fili unigenite Jesu Christe,

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris.

4. Arie — Sopran

Qui tollis peccata mundi,

miserere nobis,

suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram patris,

miserere nobis.

5. Arie — Alt

Quoniam tu solus sanctus,

tu solus Dominus,

tu solus altissimus Jesu Christe.

6. Chor

Cum Sancto Spiritu

in gloria Dei Patris, amen.

Jörg Frey

Reflection on the occasion of the performance of the Mass in F major (BWV 233) by Johann Sebastian Bach on Thursday, September 14, 2023, in the Cathedral of St. Gallen

What a wonderful music this is, dear listening community! A music that can hardly be enjoyed soberly, that carries us away and brings us into ecstasy – out of us, somewhere else. To be out of oneself – completely with God and just in this completely with us.

This is true not only for Bach’s music, but also for the text that is heard in it, especially the Gloria, which unites us with the rejoicing of the angels after the supplication of the Kyrie eleison. We know the texts in Latin, but of course they were first composed and sung in Greek and then used in many languages in the liturgy, in Coptic, Latin and of course in German. “Allein Gott in der Höh sei Ehr”, in this song version Martin Luther adopted it into his “German Mass”, and so it resounds in every Lutheran service. In the Gloria, we participate in an almost two-thousand-year history of being holy outside ourselves, we follow in the footsteps, join in the singing of the praisers of all languages and generations in the higher choir.

But it’s not that simple. Can I just get up, resolve to think positively, and escape the adversities of our lives? I don’t think so. We cannot simply praise God, also because our human language can never adequately capture the essence of God. Tradition knows that we need help, the guidance of heavenly powers, inspiration and also instruction.

That is why the Kyrie stands at the beginning of the liturgical movement in the Mass. First a petition, an invocation from the depths: “Lord, have mercy! Christ, have mercy! Lord, have mercy!” Three times this cry resounds in Greek. And those who travel in Orthodox churches know it from supplications, from litanies, often repeated: “Kyrie eleison, kyrie eleison, kyrie eleison!” Where people are in distress and see the distress of their world, where human life is at an impasse, where sickness and death threaten it, it is the call from the depths, the petition to God or to the risen Christ, who is believed to be alive and present. “Have mercy on me!” said psalmists. “Lord, have mercy!” sick people cried out to Jesus. “Kyrie eleison!” sing the choirs of the praying of all generations. A push prayer, a supplication, a prayer of the heart, a mantra. Not many words, three times the same in the rhythm of the breath. An exclamation that gives breath and freedom.

And so it is also at the beginning of the Mass, of the service. When we enter a church, especially such a wonderful space as here in the St. Gallen Cathedral, we bring many things with us, burdens, worries, inner voices. And now the sky opens up under the vault, a wide space, but not an empty space. It is not the endless expanse of the universe, but the space of the philanthropic God that arches over us. There is one who invites us oppressed ones, comes to meet us, has mercy on us in a motherly and fatherly way, because he knows us, our life, our thoughts and worries, our conditio humana. “Lord, have mercy!” I breathe out and breathe in again. “Christ, have mercy!”

In the Lutheran liturgy, this is also connected with the confession that we need God’s help, His mercy, that we are also guilty again and again and that we cannot “by our own reason nor strength”[1] rise to joyful faith and praise. And the answer that the liturgist then gives – and I am a Lutheran pastor and have often said this to people – is the affirmation: Yes, God has had mercy on you, he forgives guilt, he opens new life where ours is in a dead end. He opens a wide space. And he opens the mouth so that it can then truly praise. Only then can we sing the glorious song: “Glory and thanks be to God alone for his grace!” Gloria in excelsis Deo!

And now we stand before this grandiose hymn, composed in the 4th century from older components. It has grown and yet has a recognizable structure: two parts, addressed to God and to Christ. In front a Bible verse and at the end a Trinitarian conclusion.

I would like to begin with the first main part, the praising address to God. These are words that take us into a deep sense of wonder and that lead us in this wonder beyond our own reality. They are spoken in the form of you, in short sentences, in rhythm: “Laudamus te, benedicimus te, adoramus te, glorificamus te…” – “We praise you, we glorify you, we adore you, we extol you, and we thank you because of your great glory.” And then follow only salutations, “Lord God, heavenly King, God the Father, Almighty.” One word follows the other in rhythm. They increase, they overlap, they end in word ecstasy.

But is it okay to talk like this? May one use homemade words about God, sing homemade hymns? Private psalms – psalmi idiotici? Should one not confine oneself to the biblical psalms? Not only among Reformed people in the Netherlands and South Africa there was this discussion about psalm songs and free hymns. Even in the early church of the third and fourth centuries, such newly composed psalms were at times controversial. And so that this popular hymn, the “Laudamus te…” or its Greek version, was not forbidden, it was prefaced with a Bible word, the hymnus angelicus, the angel’s song from the Christmas story: “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, and goodwill toward men” – this is the old Luther text that Bach set to music in his Christmas Oratorio, or more correctly according to the oldest Greek and also the Latin text: “to men of goodwill”, that is, to men in whom God is well pleased.

In the end, it is not about us feeling good – that too! But God is thanked for the fact that he is well-disposed to his creatures, that he is well-disposed to us and does us good. In concrete terms, in the biblical story: that he came into this world and to us human beings, in the birth of Jesus, the Savior, in the incarnation of the divine Word, which is sung about first by the angels and then also by human beings. “Gloria in excelsis Deo” (Glory to God in the highest) – and peace on earth! Shalom – Eirene – Pax. These are God’s thoughts for his world. Contrast program for a world of oppression and discord.

With the word from the Christmas story, the hymn is preceded by a key. Like a clef before the music. The framework for everything that follows is set. And it is explained why we can even begin to praise God ourselves: Because he has shown himself in the story of Jesus, in his words and deeds, and in what, according to early Christian interpretation, is the most important thing: in the forgiveness of sins, in the opening of new life, in the fact that I can start anew, even where my life is at a dead end. The praise of God is more than amazement at the sublime. It goes back to a reason: this reason is in the story of Jesus Christ, in whom God has shown himself as turned towards us.

Therefore, in the second part of the hymn, Jesus Christ is addressed, again in a series of predications that pass almost imperceptibly from addressing God to addressing Christ.

If before it was Deus Pater omnipotens (God, Father, Almighty), it continues with Domine Fili unigenite (Lord, only begotten Son), Jesus Christ, Lord, God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father. The praise is now for Jesus Christ, whose origin, according to the beginning of John’s Gospel, is in the eternity of God: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and God was the Word.”[2] This is elaborate mythology that connects heaven and earth: The Word of God that became flesh did not have its origin in human will, nor in a miraculous birth. The Logos came forth from the Father before all time. He is the Word of God, the Word of devotion, of love. That is why Jesus Christ is “glorified equal” with God. He is not a second God, but the word of the one God, the promise, the eternal yes.

And therefore Christ is now addressed to his action: “You who take away the sin of the world, have mercy on us! Who takest away the sin of the world, receive our supplications; who sitteth on the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us!” In praise, Christ is not distant past, but present, there with God for the people. In praise, heaven on earth is present. That is why in the hymn here – only very briefly – there is also a petition: “Have mercy on us; accept our supplication!” – hear us! It is an address to a living counterpart.

Following this, a threefold “solus” comes up. Christ is “alone the Holy One, alone the Lord, alone the Most High” – he alone is the Word of God in which God is spoken, he alone is the one in whom God wants to come close to us.

Such words gain weight where faith is called into question, where other powers want to dispute its place. In the Reformation era, “solus Christus, sola fide, solo verbo” (Christ alone, by faith alone, by the Word alone). Or even in the time of National Socialism, where the Swiss theologian Karl Barth formulated: “Jesus Christ … is the one Word of God, which we have to hear …”[3] No other criteria may apply. Not Christ and the emperor, Christ and the people, Christ and mammon. No: “You alone are the Holy One”, in whom God comes close to us.

And so the praise of Christ leads to the Trinitarian praise “cum Sancto Spiritu in gloria Dei Patris”. At the end there is again God, who is “all in all” (1 Cor. 15:28). From him goes forth the movement of salvation, toward him goes the movement of praise again. All in all.

It is a dense text, a soaring text. For a long time, the Gloria was sung only on particularly high feast days, at Christmas and other festivals, and it could be intoned only by the bishop. Only since the high Middle Ages has it been part of the fixed canon of the Mass. Perhaps also because now the honor of God had to be emphasized over the honor of the emperor. Perhaps there is also a truth in this: He who honors God and gives thanks to Him is free from human claims, he can keep his head straight and stand upright, because the powers of this world are relative, and peace is pronounced on the people of His good pleasure. I want to let this be valid, for me and for this world. And the old texts of the praise of God help for it.

So let us immerse ourselves once again in the music, the fervent plea for God’s mercy and the ecstatic praise of God that takes us beyond our reality so that we may find peace in it.

[1] Thus the formulation of Martin Luther in his Small Catechism in the explanation of the third article of faith.

[2] Joh. 1, 1.

[3] Barmer Theological Declaration, 1st Thesis.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).