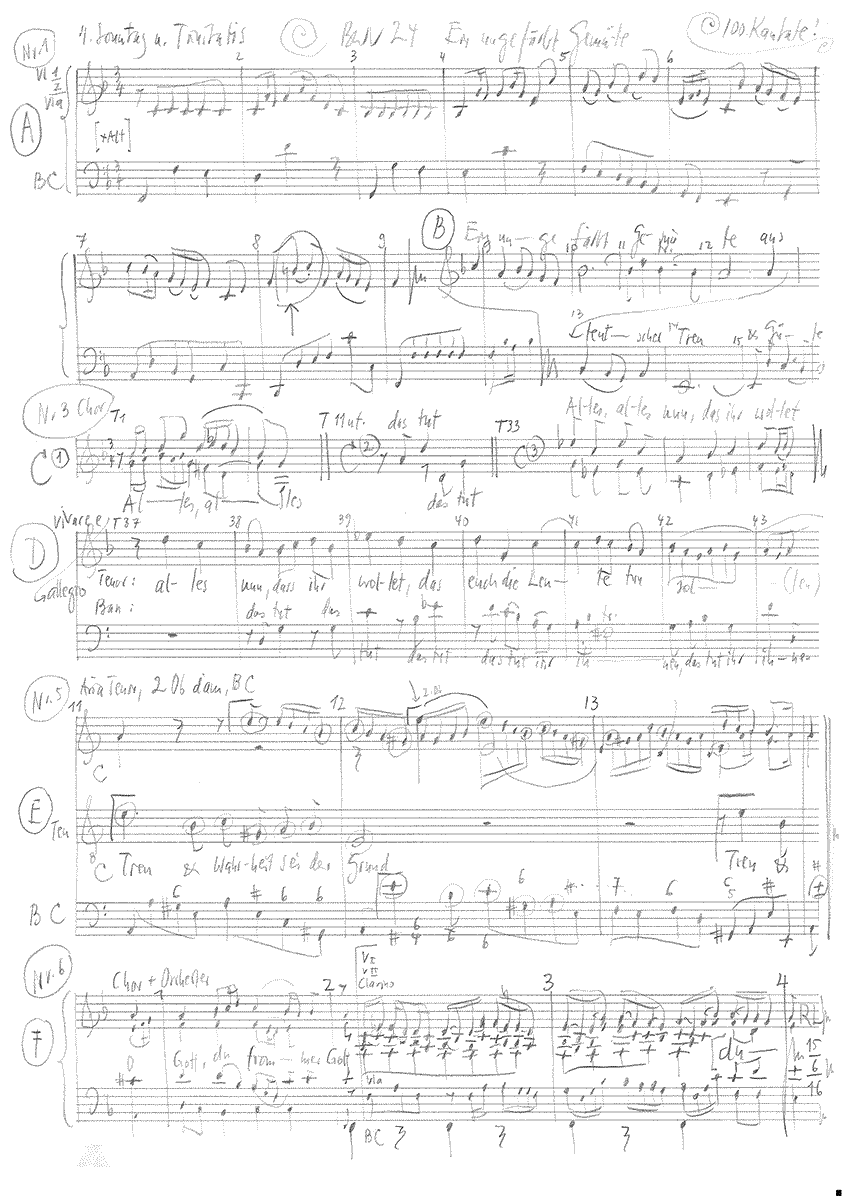

Ein ungefärbt Gemüte

BWV 024 // For the Fourth Sunday after Trinity

(An undisguised intention) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, oboe díamore I+II, trumpet, strings and basso contiuno

Although cantata BWV 24, “An undisguised intention”, was first performed on 20 June 1723 in Leipzig, it is related in tone to Bach’s Weimar cantatas, perhaps to provide stylistic unity with cantata BWV 185, “O heart filled with mercy and love everlasting”, which was reperformed in the same church service. The libretto by Erdmann Neumeister, which rebukes and woos by turn, sets the stage for an unmistakably moralising cantata that was well suited to performance in the vice-ridden commercial cities of Leipzig and Hamburg.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Mirjam Wernli Berli, Olivia Fündeling, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel, Anna Walker

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Liliana Lafranchi, Damaris Rickhaus, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Sören Richter, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Valentin Parli, Daniel Pérez, Retus Pfister, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Yuko Ishikawa, Elisabeth Kohler, Olivia Schenkel, Anita Zeller

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Zimmermann, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp

Oboe d’amore

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Aleida Assmann

Recording & editing

Recording date

17.06.2016

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 2, 4, 5

Erdmann Neumeister, 1717

Text No. 3

Matthew 7:12

Text No. 6

Johann Heermann, 1630

First performance

Fourth Sunday after Trinity,

20 June 1723

In-depth analysis

The introductory aria is unusually catchy in nature, with the alto soloist accompanied by a continuo part that alternates between leisurely strides and sprightly movements. The repeated notes of the unison strings, too, could be interpreted as a currish gait or a sneering stance – but they may equally stand for the natural wholesomeness of a simple citizen of Thüringen, who, with his “faith and kindness”, reveals a certain charm “before God and man” and even dares choose a contested direction on “life’s compass”. Indeed, this unsophisticated but kind-hearted fellow may be a self-portrait of Bach himself. Yet the “undisguised” motive also calls to mind the noble simplicity of idealised ancestors, as found, for example, in Telemann, whose “Ouvertüre des Nations anciennes et modernes” was seemingly a bespoke composition for the ancient Germanic peoples. Such a character topos captures the stereotype of German selfperception in early modern times – an identity based on a clear disassociation from the fickleness of a foreign Pope and the menial fawning at the Spanish-Habsburg imperial court.

The tenor recitative then raises the moral discourse to a firm level. In this setting, the rare virtue of “sincerity” is distinguished as one of “God’s most gracious blessings”, which is then countered with a pessimistic understanding of humanity – God alone can preserve us from our “evil contrivance”. This leads into an arioso conclusion, expressed with the full grace of virtue, that declaims the golden rule: “Upon thyself impress the form, Which thou wouldst have thy neighbour own”. The tutti chorus then reinforces this message with a Bible verse from Matthew 7:12, finally employing the fullensemble sound of choir and orchestra, and adding a solo trumpet. With this double setting of the text, Bach returns to a successful approach from his first Leipzig cantatas, which often comprised a paired setting of a concertante prelude and a vocal fugue that successively increased in voicing (vocal solos + instruments + vocal ripieno). This chorus, which resembles a collective self-admonishment, thus acts as a postponed “opening movement” of the cantata; the complexity of the successive entries evokes the difficulty of truly seeing conflicts through the eyes of others.

Set to an accompagnato of hammer-like blows, the bass recitative attacks the devilish vice of hypocrisy, before taking falseness to task. In quasi buffoonish twists and turns, the music unmasks the “monsters” disguised as angels as well as the proverbial “wolf in sheep’s clothing”. The arioso conclusion “May God above protect me now from this” thus approaches a hypocritical theatricality that recalls a caricature of a sanctimonious pulpiteer.

This mood is countered in the tenor aria by a hermetic world of “trust and truth” that nonetheless radiates warmth through the mellow timbre of the oboes d’amore. Here, the listener can retreat from the vice-ridden marketplace into a cosy room – perhaps one where grace is being said over a meagre, but lovingly prepared meal. While the imitative entries suggest followers of Christ, the motive of jolting, downward leaps plays on the difficulty of living a life of virtue. Ultimately, the aria imparts that only the unity of word and deed can make us “God and angels like”; the setting’s use of through-composed form rather than dacapo form is an apt reflection of this message.

Surprisingly, the chorale prayer “O God, thou righteous God” is not set in simple fourpart harmony, but instead features rich orchestration and instrumental episodes that, particularly through the low repeated notes of the trumpet part, recall the opening movement – indeed, Bach treats this chorale with an opulence and tenderness that is almost prescient of Mendelssohn. In this setting, the inner joy of a magnanimous spirit is revealed, while the interspersed sighs suggest the difficulty of abiding by Neumeister’s injunctions to his flock. The dense melodic progression that Bach assigns to the “uncorrupted” soul evokes a group of pilgrims huddled together in prayer against a storm; the chorale then closes with an extended phrase of rapturous tenderness. We can only speculate on whether the merchants and guild masters of Leipzig ultimately settled their bill of exchange to the Kingdom of Heaven – Bach and Neumeister, for their part, did all they could to honour such debts, and in doing so reached beyond the ancient Germanic tribes to all Christian people.

Libretto

1. Arie (Alt)

Ein ungefärbt Gemüte

an teutscher Treu und Güte

macht uns vor Gott und Menschen schön.

Der Christen Tun und Handel,

ihr ganzer Lebenswandel

soll auf dergleichem Fuße stehn.

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Die Redlichkeit

ist eine von den Gottesgaben.

Dass sie bei unsrer Zeit

so wenig Menschen haben,

das macht, sie bitten Gott nicht drum.

Denn von Natur geht unsers Herzens Dichten

mit lauter Bösem um;

soll’s seinen Weg auf etwas Gutes richten,

so muss es Gott durch seinen Geist regieren

und auf die Bahn der Tugend führen.

Verlangst du Gott zum Freunde,

so mache dir den Nächsten nicht zum Feinde

durch Falschheit, Trug und List.

Ein Christ

soll sich der Tauben Art bestreben

und ohne falsche Tücke leben.

Mach aus dir selbst ein solches Bild,

wie du den Nächsten haben willt.

3. Chor

Alles nun, das ihr wollet,

dass euch die Leute tun sollen,

das tut ihr ihnen.

4. Rezitativ (Bass)

Die Heuchelei

ist eine Brut, die Belial gehecket;

wer sich in ihre Larve stecket,

der trägt des Teufels Liberei.

Wie? lassen sich denn Christen

dergleichen auch gelüsten?

Gott sei’s geklagt! die Redlichkeit ist teuer.

Manch teuflisch Ungeheuer

sieht wie ein Engel aus:

Man kehrt den Wolf hinein,

den Schafspelz kehrt man raus.

Wie könnt es ärger sein?

Verleumden, Schmähn und Richten,

Verdammen und Vernichten

ist überall gemein.

So geht es dort, so geht es hier.

Der liebe Gott behüte mich dafür!

5. Arie (Tenor)

Treu und Wahrheit sei der Grund

aller deiner Sinnen;

wie von aussen Wort und Mund,

sei das Herz von innen.

Gütig sein und tugendreich,

macht uns Gott und Engeln gleich.

6. Choral

O Gott, du frommer Gott,

du Brunnquell aller Gaben,

ohn den nichts ist, was ist,

von dem wir alles haben,

gesunden Leib gib mir,

und dass in solchem Leib

ein unverletzte Seel

und rein Gewissen bleib.

Aleida Assmann

“Alliance of Faith and Reason”.

On music as a dimension of religious experience – a reading of the cantata “Ein ungefärbt Gemüte” (BWV 24) as a drama in 6 acts.

In his memoir “Granatsplitter”, the German literary theorist and publicist Karl-Heinz Bohrer tells of his youth in a Protestant boarding school. As a Rhineland Catholic, he also had contact there with the Protestant pastor who looked like Luther and whose sermons were famous. But all this could not really convince the young driller, “although the sermons of the Protestant pastor seemed great to him, quite great. The words piled up, but that was just it – there were too many words”. The boy told the pastor his impression: “in the Protestant church there was too much talking, but too little showing. (…) Then the Protestant priest laughed and said: ‘You are still a real Catholic!

Talking too much, showing too little: here Bohrer reformulates the old contrast between Protestant word culture and Catholic image culture, which also includes a rich spectrum of sensual impressions such as vestments, jewellery, precious relics and incense, with which the sacred is lifted out of the sphere of the everyday. In the juxtaposition between the ear and the eye, however, something essential is lost, and that is the significance of music as a special dimension of religious experience. In the chants of the monks, in chorales and festive masses, music has always had a firm place in the history of Christianity as a support for prayer and liturgy. In Protestantism, however, this music changed its character and developed into a new subjective dimension of religious experience. 40 years before Bach’s birth, the Puritan poet John Milton had already expressed this in the poem “Il Penseroso”:

“And when the organ’s rich sound

Mingles with a choir of strong voice

In worship in hymns clear

then the sweetness penetrates my ear,

it dissolves me in pure delight

and lets me gaze into the heavens”.

(Trans. A. A.)

“There let the pealing organ blow,

To the full voic’d Quire below,

In service high, and anthems cleer,

As may with sweetnes, through mine ear,

Dissolve me into extasies

And bring all heaven before mine eyes.”

(verses 161-166)

Here, too, something penetrates through the ear, but it is not only the piling up words, it is also the music that in Bach finds its addressee in the individual and in this way opens up a new dimension of religious experience. Under the conditions of Protestant culture, Bach produced a new fusion of music, religion and subjectivity that has an impact far beyond the boundaries of worship and Christianity.

The composition of the cantata “Ein ungefärbt Gemüte” (BWV 24) consists of the three elements aria, recitative and choir, each of which is repeated. This gives rise to six sections which are held together by the common theme of Christian living.

(1) The first aria is sung by a female voice. The text by Erdmann Neumeister from 1717, which Bach used as a basis, consists of a general statement and a subsequent instruction:

“Ein ungefärbt Gemüte

of German faithfulness and goodness

makes us beautiful before God and man.

The Christians’ doings and dealings,

their whole way of life

should stand on such a footing.”

Here we are not talking about the individual, faith or religious experience, but about behaviour and ways of life in ever larger groups: Germans, Christians and the whole of humanity. Religion – this is a very current thought today – involves not only being at peace with one’s God on the inside, but also living peacefully in one’s environment on the outside. Christianity should make its followers “beautiful” not only before God, but also towards people.

This prelude is followed by two recitatives, also from Neumeister’s pen, which elaborate on this question of right living together. They are designed as a pair of opposites and present the Christian doctrine of behaviour under a positive and a negative sign: as the virtue of honesty and the vice of hypocrisy.

(2) The virtue of honesty is so little used because, according to Protestants, it is not inherent and anchored in the nature of man. Unlike the Enlightenment thinkers, the Protestants had a pessimistic view of man:

“For by nature the thoughts of our hearts

deals with pure evil;

If it is to direct its path to something good,

God must govern it by his spirit

and guide it along the path of virtue.”

Man’s normal mode of operation is being attracted to evil. To get away from it requires divine support and intervention. But being at peace with God is not enough either:

“If thou desirest God for a friend,

do not make your neighbour your enemy.

(…)”

The pious person shows himself in society as a person of solidarity. Peaceful coexistence demands respect for the other, who must not be deceived by trickery or taken advantage of by deceit. In this recitative on honesty, there is no mention of the image of man in the image of God, which gives man his value and dignity. Instead of a universal statement about man, it is about a concrete rule for social coexistence:

“Make of thyself such an image

as you would have your neighbour be!”

Here an important step is taken from the vertical to the horizontal relationship: man is not only the image of God, he should also live in such a way that he can be an example for the next. This is the same power that emanates from the mysterious ring in Lessing’s “Nathan the Wise”, which, if worn with the right confidence, makes its owner “pleasing in the sight of God and man”, as it says in Act III:

“Before grey years lived’ a man in the East,

Who possessed a ring of inestimable value

From a dear hand possessed. The stone was an

Opal that played a hundred beautiful colours,

And had the secret power to make pleasant in the sight of God

And to make pleasant in the sight of men, whoever

In this confidence wore it.”

(4) Every virtue casts a shadow and has as its reverse a vice associated with it. Therefore, parallel to the 1st recitative, which paints the virtue of honesty, the 2nd recitative paints the vice of hypocrisy. Vices have become much more prevalent in the imagination of Christianity than virtues. The dualism between good and evil has become a mythical battle in the heart of man, in which God and Satan fight for the soul. In a poem by the 17th century English poet Francis Quarles (1592 – 1644), this struggle is compared to a tennis match:

“Man is a tennis court,

his body the wall,

the players God and Satan

his heart the ball.”

(Trans. A. A.)

“Man is a tennis court

His Flesh’s the Wall

the players God and Satan

the heart’s the ball.”

The model for the vice of hypocrisy is the devil himself, who sneaks into the human heart in all kinds of disguises to tempt it and bring it down. This perpetual struggle of good and evil, which has occupied a large place in the imagination of Christians, has been further exacerbated by Protestantism. Whereas in Catholicism a great army of saints and helpers, led by Mary, the Mother of God, intercedes for the individual soul, the Protestant is alone in the open field at the mercy of an equally great army of dangerous demons and seducers, all of whom are embodiments of the devil. In Bach’s cantata, the devil appears in the figure of Belial and is the master of dissimulation. This is also how Milton portrayed him in his epic of Paradise Lost. He can change his shape at will and appears as a toad on the ear of Eve, to whom he gives a disturbing dream during the night in Paradise. He can easily outwit the angels who keep watch in Paradise, for angels, as Milton points out, are absolutely pure and therefore guileless. They have no eye for deception and dissimulation. Only one of them, named Ithuriel, has a special tool, a spear, at the touch of which any pretence is immediately transformed back into its real form. The Swiss painter Johann Heinrich Füssli depicted this scene in a famous painting in 1779:

When he now saw the [i. e. Satan],

Who so eagerly, Ithuriel only lightly

Touched with his spear, he leaps up,

Discovered and surprised, changed back.

For falseness holds not touch with

Heavenly purified form,

It returns to its own image,

And with violence.

‘Him [i. e. Satan] thus intent Ithuriel with his spear

Touched lightly; for no falsehood can endure

Touch of celestial temper, but returns

Of force to its own likeness.’

(Book IV, 810 – 813)

With this miracle weapon, which puts a quick end to the haunting, the angels can unmask Satan and remove him from Paradise again for a while. In the fallen world there is no longer any unity between the outside and the inside; here there is constant insecurity due to diabolical and human disguises. One can never conclude with certainty from the outer behaviour to the inner intentions of a human being.

Because of his art of disguise, Satan was also seen as the patron saint of actors, which is why the theatres were closed in Puritan England. We all act – this insight was written by none other than Shakespeare on the stage of his Globe Theatre: Totus mundus agit histrionem. This insight was confirmed in the 1970s by the sociologist Ervin Goffman, who defined life as a stage on which all people have to slip into the roles that society sets for them. ‘We are all performers!’ is the modern claim of self-presentation in everyday life. Mask and pretence, according to Goffman, are an important element of social interaction: if everyone masters and performs their roles well, social interaction can succeed.

But even today there is a Protestant reservation against role-playing because it is externally determined, i.e. not ‘authentic’, and thus stands in the way of ‘self-realisation’. At that time, people condemned this role-playing because it opened the door to the strategic exploitation of the other. The origin of anti-social behaviour was rightly recognised in cunning, deceit and pretence. Fellow human beings are hoodwinked because, to use Kant’s words, they are not recognised as an end but are used as a means to one’s own advantage. This erosion of social solidarity is only the beginning of further stages of ‘anti-social’ behaviour:

“slandering, vituperating and judging,

condemning and destroying

is common everywhere.”

(3) The two recitatives on probity and hypocrisy frame the first chorus, which sums up the whole theme of the cantata in a single sentence:

“Everything now that you want / people to do to you, / you do to them.”

This sentence formulates the ‘Golden Rule’, which summarises four thousand years of empirical wisdom spread throughout the world. There are biblical sources for this aphorism from the so-called Old Testament (Lev 19:18; Tobit 4:15) and the New Testament (Mt 7:12 and Lk 6:31). Even today it is well known in the vernacular:

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

This formula teaches us that the hardest thing in the world, the preservation of social peace, is actually quite simple if we really take seriously the principle of the reciprocity of human interaction. Hegel put it in an even shorter formula: “The doing of one is the doing of the other.” This applies in good through mutual regard, respect and probity, as it does in evil through contempt, exploitation and violence. The ‘Golden Rule’ is at the heart of Bach’s cantata, linking biblical and secular wisdom; piety and humanity; religion and enlightenment; faith and reason. This insight applies within groups and across group boundaries, so it connects Germans and Christians with people of all backgrounds. The last two stanzas round off the theme.

(5) The second aria follows on from the main motif of the cantata: “an uncoloured mind”, based on the correspondence of “outside” and “inside”, brings heaven down to earth, for it makes us humans equal to God and angels.

equal.

(6) This unity of “outside” and “inside” is requested and accomplished in the common prayer of the final chorale. It is not a matter of a healthy spirit in a healthy body, as the Greeks would have it, but of a soul of integrity and a pure conscience in a healthy body.

With this final chord, the cantata ends and with it the tension between concord and discord, between honesty and hypocrisy. Bach’s music and his important text build a bridge from the imagery of the Baroque to the rationality of the Enlightenment; in this impressive composition, the boundaries between Christian ethos and secular ethics become blurred. The text refers back to Lessing’s Ring Parable and Kant’s Categorical Imperative of 1785 (“Act in such a way that the maxim of your will can at the same time be regarded as the principle of a general law”), and at the same time anchors both in the biblical and Protestant tradition, while also drawing on ancient wisdom. The cantata is a form of sermon in which, however, the words do not pile up, but are set in vibration by the music. There is indeed a great deal to hear here, but on the wings of the music the words are not only understood, but also shown, sensually experienced and forcefully felt.

Literature

– Karl-Heinz Bohrer, Granatsplitter. Erzählung einer Jugend, DTV, Munich 2014.

– Ursula Geitner, The Language of Dissimulation. Studies on rhetorical and anthropological knowledge in the 17th and 18th centuries, Niemeyer, Tübingen 1992.

– Erving Goffman, We All Play Theatre. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Piper, Munich Zurich, 2003.

– Immanuel Kant, Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten, Reclam, Stuttgart 2001.

– Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan the Wise, A dramatic poem in five acts, Reclam, Stuttgart 2000.

– John Milton, Paradise Lost and L’Allegro, il Penseroso in: The Poems of John Milton, edited by John Carey and Alastair Fowler, Longmans, London 1968.

– John Milton, Das verlorene Paradies, translation by Hans Heinrich Meier, Reclam, Stuttgart 1968 et al.

– Francis Quarles, Divine Fancies, London, John Williams 1632.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).