Gottlob! nun geht das Jahr zu Ende

BWV 028 // Sunday after Christmas

(Praise God! For now the year is ending) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, cornett, trombone I–III, oboe I+II, taille, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden; preiset ihn, alle Völker! Denn seine Gnade und Wahrheit waltet über uns in Ewigkeit. Halleluja!

Ich sage aber: Solange der Erbe unmündig ist, so ist zwischen ihm und einem Knechte kein Unterschied, ob er wohl ein Herr ist aller Güter; sondern er ist unter den Vormündern und Pflegern bis auf die Zeit, die der Vater bestimmt hat. Also auch wir, da wir unmündig waren, waren wir gefangen unter den äusserlichen Satzungen. Da aber die Zeit erfüllet ward, sandte Gott seinen Sohn, geboren von einem Weibe und unter das Gesetz getan, auf dass er die, so unter dem Gesetz waren, erlöste, dass wir die Kindschaft empfingen.

Und sein Vater und seine Mutter verwunderten sich des, das von ihm geredet ward. Und Simeon segnete sie und sprach zu Maria, seiner Mutter: «Siehe, dieser wird gesetzt zu einem Fall und Auferstehen 57 vieler in Israel und zu einem Zeichen, dem widersprochen wird (und es wird ein Schwert durch deine Seele dringen), auf dass vieler Herzen Gedanken offenbar werden.» Und es war eine Prophetin, Hanna, eine Tochter Phanuels, vom Geschlecht Asser; die war wohl betagt und hatte gelebt sieben Jahre mit ihrem Manne nach ihrer Jungfrauschaft und war nun eine Witwe bei vierundachtzig Jahren; die kam nimmer vom Tempel, diente Gott mit Fasten und Beten Tag und Nacht. Die trat auch hinzu zu derselben Stunde und pries den Herrn und redete von ihm zu allen, die da auf die Erlösung zu Jerusalem warteten. Und da sie es alles vollendet hatten nach dem Gesetz des Herrn, kehrten sie wieder nach Galiläa zu ihrer Stadt Nazareth. Aber das Kind wuchs und ward stark im Geist, voller Weisheit, und Gottes Gnade war bei ihm.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

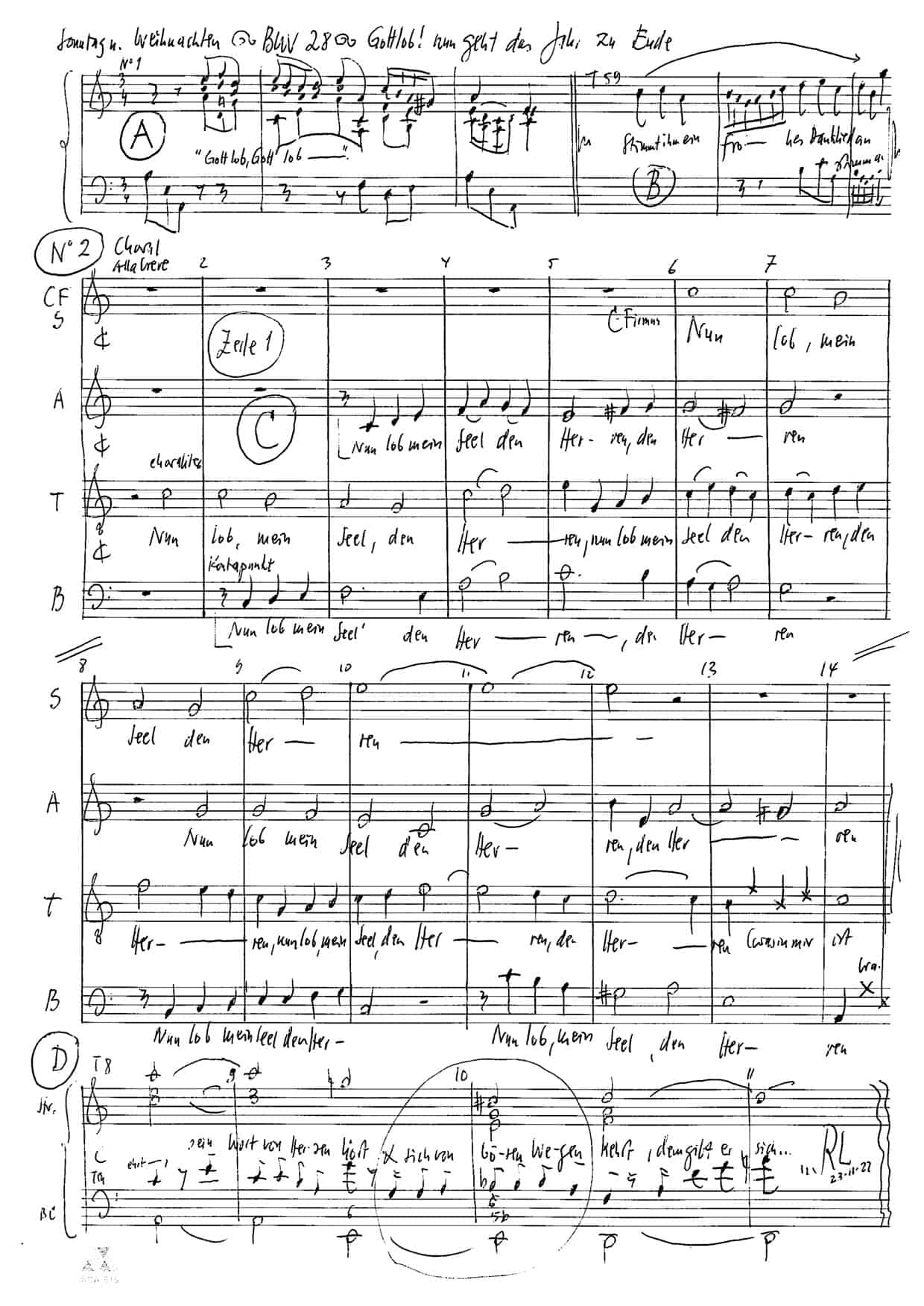

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Jessica Jans, Lena Kiepenheuer, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Stefan Kahle, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Manuel Gerber, Tobias Mäthger, Walter Siegel

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Israel Martins, Valentin Parli, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler, Petra Melicharek, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Cornett

Frithjof Smith

Trombone

Simen van Mechelen, Henning Wiegräbe, Joost Swinkels

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Philipp Wagner

Taille

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Markus Gabriel

Recording & editing

Recording date

16/12/2022

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Kirche St. Mangen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

30 December 1725, Leipzig

Text

Erdmann Neumeister (movements 1, 4, 5); Johann Gramann (movement 2); Jeremiah 32:41 (movement 3); Paul Eber (movement 6)

Libretto

1. Arie — Sopran

Gottlob! Nun geht das Jahr zu Ende,

das neue rücket schon heran.

Gedenke, meine Seele, dran,

wieviel dir deines Gottes Hände

im alten Jahre Guts getan!

Stimm ihm ein frohes Danklied an!

So wird er ferner dein gedenken

und mehr zum neuen Jahre schenken.

2. Choral

Nun lob, mein Seel, den Herren,

was in mir ist, den Namen sein!

Sein Wohltat tut er mehren,

vergiß es nicht, o Herze mein!

Hat dir dein Sünd vergeben

und heilt dein Schwachheit groß,

errett’ dein armes Leben,

nimmt dich in seinen Schoß,

mit reichem Trost beschüttet,

verjüngt, dem Adler gleich.

Der Kön’g schafft Recht, behütet,

die leiden in seinem Reich.

3. Rezitativ und Arioso — Bass

«So spricht der Herr: Es soll mir eine Lust sein, daß ich ihnen Gutes tun soll; und ich will sie in diesem Lande

pflanzen treulich, von ganzem Herzen und von ganzer Seelen.»

4. Rezitativ — Tenor

Gott ist ein Quell, wo lauter Güte fleußt,

Gott ist ein Licht, wo lauter Gnade scheinet,

Gott ist ein Schatz, der lauter Segen heißt,

Gott ist ein Herr, der’s treu und hertzlich meinet.

Wer ihn im Glauben liebt, in Liebe kindlich ehrt,

sein Wort von Herzen hört

und sich von bösen Wegen kehrt,

dem gibt er sich mit allen Gaben:

Wer Gott hat, der muß alles ha

5. Arie Duett — Alt und Tenor

Gott hat uns im heurigen Jahre gesegnet,

daß Wohltun und Wohlsein einander begegnet.

Wir loben ihn herzlich und bitten darneben,

er woll auch ein glückliches neues Jahr geben.

Wir hoffen’s von seiner beharrlichen Güte

und preisen’s im voraus mit dankbarm Gemüte.

6. Choral

All solch dein Güt wir preisen,

Vater in’s Himmels Thron,

die du uns tust beweisen,

durch Christum, deinen Sohn,

und bitten ferner dich:

Gib uns ein friedsam Jahre,

für allem Leid bewahre

und nähr uns mildiglich!

Markus Gabriel

Ladies and Gentlemen,

After we have become witnesses, contributors, co-knowers of the revelation of the beautiful, it is my task as a philosopher to fulfill the imperative “remember!”, which is why today I will offer some reflections, that is, reflections of this beautiful, which we now still carry in our souls and will repeat in a moment, on the basis of three themes, which, I believe, this cantata traverses particularly masterfully: the beautiful, the good and God. That is to say, three themes which, in this dark time whose end we wish for – “Gottlob! Now the year comes to an end” – are especially needed.

Let us begin with the beautiful: the beautiful, one can say, is the self-reference, the self-reference of art. Art is the paradigmatic putting-into-work of beauty. It is, as the great philosopher Plato said a little more than two millennia ago, that which stands out most among all that exists: the ekphanestaton tôn ontôn, that which shines. The beautiful, then, is the self-reference, the self-referentiality of art. And Bach, we can say, by choosing these texts, if we look into the cantata text now, works quite consciously and in the usual master class in which he moves, with this characteristic of art. It starts with “gottlob!” which is not only the exclamation, but of course also the announcement of what will now follow: a praise of God. And I also believe that ironically, as he was – on the musical level this is well known and well analyzed, and the choice of lyrics also reveal this – he naturally does not hold back with a little hint as to who is actually in control of the composition here. If it is said: “God is a spring, where loud goodness flows”, then one could also say: God is a brook. That’s the quality of art I’m talking about – and I’ll point out a few other passages in our cantata. He works, of course, the movement of that self-reference into the scale that we all appreciate, that we have developed an ear for. He works with it, of course, but also the use of the text, especially in this cantata, is particularly impressive. God is, as I said, a fountain where pure goodness gushes. But God is also a light, where pure grace shines. Or as the great philosopher Hegel defined art: Art is the “sensual appearance of the idea”. The sensual appearance of the idea and the idea is here the idea of the good. In art, the good shines through in a way that cannot be replaced. There is no substitute for art and there is no substitute for this work. I can comment on the work for a lifetime and it will never be possible to exhaust it through that, through my commentary. Because, as I had begun my reflection, we all participate in the interpretation of the work: the performers, by bringing the work to life, and we, the listeners, who make sure that we are the resonance work, the sounding board of this work. The work cannot exist without the listeners. Even the artist who composes the work is hearing the work for the first time. The artist is also dependent on his work. No one is above the work of art. Therefore, this work of art deliberately seeks closeness to God. I will come to this in my concluding short reflections, with references to and on God the cantata does not spare.

Bach also works with the fact that, of course, the poet he quotes, Erdmann Neumeister, already uses this characteristic of art himself in sentences 1, 4 and 5. The word “new” occurs only in these sentences. The “new master” makes an appearance here, because the new year that is now approaching is, after all, the year that the lyrical I, that is, the one who sings here, summons and that speaks to us in this form of setting, in the various levels that art offers: visually the light, vocally – we are dealing with the vocal work here – and, of course, above all through the music and its own imagery. So that’s the beauty, the self-referentiality of art, and you will observe this form of self-referentiality in every great work of art. That is precisely the essential difference between kitsch, Madonna – excuse me for associating something like that with Bach and calling it up here – and what we have heard today. Or, if I may say so, between Goethe and Kim de l’Horizon, where the contrast is even greater. There is also self-reference in Madonna, but Bach’s Cantata has various levels of a composition that cannot be traced back to a few patterns; for every work of art, and that is why art is particularly impressively embodied in music, every work of art is in its essence composition. That means the arrangement of elements, which is irretrievable and possible exactly in this way only once. That is why every performance of a cantata is ultimately another work in which we participate. And if you will, this work, this cantata, is something that continues throughout time, as the sum of all the successful performances of this work. The work is not what you see in the musical text, the work is not what you have heard once, but the work is what repeats itself infinitely in each of us. As I said, you are the sounding board of the beautiful. That is part of the human dignity that is in danger today. This brings me to the good.

The good is the foreign reference of the beautiful, that is, the good is the place that the beautiful finds in its time. The beautiful and the good are related. The doing of the morally right and the higher success, the successful life are banished or like the sentences of Neumeister, set to music by Bach. Doing good and being good meet each other. Benevolence, the doing of the morally right, and well-being, the experience of the beautiful, meet each other in the blessing of this work. Blessing also occurs exactly twice in the text. Once as a blessing that God gives, and in the fact that God has blessed us in this year through the encounter, as the text says, of doing good and being good, and through this the prospect of a new year opens up, whose goal is, then as especially today, that we, humanity, turn from evil ways. And this succeeds only by listening to God’s word from the heart, at least this work says to us.

And what does it mean to hear a word of God from the heart? Well, it means to be contributors to the continuous creatio continua of this work. It means to hear God’s word from the heart, to participate in the performance of this work by being a sounding board for something absolute.

And that brings us to God, and there I will say less. God is dangerous territory for philosophers and I’m still too young to write a book about God, I’d like to wait until I’m eighty if I can get it done by then. To date I am cautious, even if the “Sternstunde Religion” will probably motivate me next year to comment on God on Swiss television, and yet I do so here more cautiously. God is something, says St. Anselm, that is greater than anything we can think. Well known is a formula of his, according to which God is the greatest thing we could think, therefore God necessarily exists. But he continues with the idea that God is greater than anything we could think, and therefore ultimately not a subject of philosophy. God is a subject of revelation, and one way in which God reveals Himself is through the figurative language not only of the Bible and other sacred texts, but also of the tonal language we have heard today, which works precisely with the fact that it is possible to make God visible without clearly saying who or what God is, or as the Bible teaches us: God has never been seen, God has not been seen by anyone, God is the invisible and therefore the point of contact of the beautiful and the good. There, where the beautiful and the good meet in a revelation, there God produces himself in his image. We cannot know more and therefore I end mildly at this point and look forward to the repetition of this great cantata in master form by our “Neumeister”. Thank you very much!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).